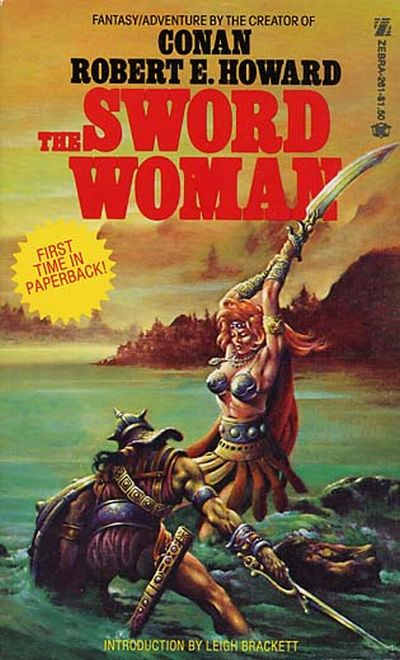

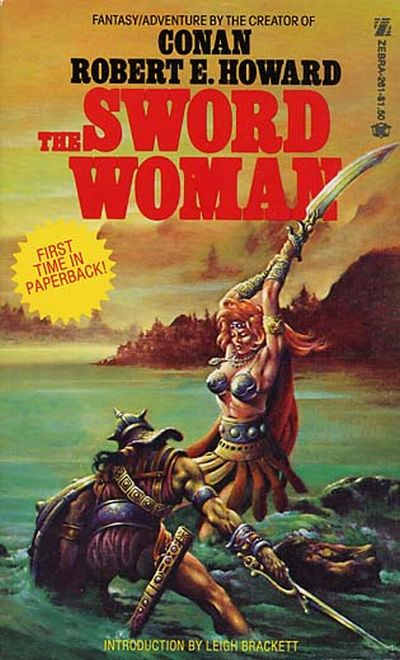

This collection of five short pieces by pulp era master of rough-and-tough fiction Robert E. Howard includes two unfinished story or novel fragments dealing with barbarian heroes in the Conan mold. But the focus of this review is on the title story and two others, “Blades for France” and “Mistress of Death” (the latter completed by Gerald W. Page after REH’s death), which are the only Howard stories that feature one of his most striking and memorable characters, “Dark” Agnes de Chastillon, sometimes called, in medieval/early modern fashion, Agnes de la Ferre, after her home village. (There’s another collection that uses the same title story and also includes “Blades for France;” but it only includes one –or possibly both, I’m not sure– of the fragments later used by Page to complete the third story.) These tales are first-rank parts of the Howard canon, and my five-star rating above refers just to them. They’re violent, gritty tales of historical action-adventure, with a tone like that of the Conan and Kull stories but mostly without supernatural elements. (A wizard does appear as the villain in “Mistress of Death.”)

This collection of five short pieces by pulp era master of rough-and-tough fiction Robert E. Howard includes two unfinished story or novel fragments dealing with barbarian heroes in the Conan mold. But the focus of this review is on the title story and two others, “Blades for France” and “Mistress of Death” (the latter completed by Gerald W. Page after REH’s death), which are the only Howard stories that feature one of his most striking and memorable characters, “Dark” Agnes de Chastillon, sometimes called, in medieval/early modern fashion, Agnes de la Ferre, after her home village. (There’s another collection that uses the same title story and also includes “Blades for France;” but it only includes one –or possibly both, I’m not sure– of the fragments later used by Page to complete the third story.) These tales are first-rank parts of the Howard canon, and my five-star rating above refers just to them. They’re violent, gritty tales of historical action-adventure, with a tone like that of the Conan and Kull stories but mostly without supernatural elements. (A wizard does appear as the villain in “Mistress of Death.”)

Howard was not as constrained by the sexist attitudes of his day as many of his contemporary pulp writers were. So some of his writings are trail-blazers in terms of female roles. Where women in pulp action yarns were usually passive, meek and needing rescue (or sinister and sneaky, wreaking their evil by stealth and treachery), Howard dared to actually portray some women who step out of the damsel-in-distress mode to pick up lethal weapons and use them;. But they don’t lose their moral compass as a result, so that they’re genuine heroic figures rather than villainesses.

Conan sidekicks Valeria in “Red Nails” and pirate queen Belit in “Queen of the Black Coast” come to mind (actually, since she’s Conan’s boss in the latter story, one could argue that he’s her sidekick there!), as does Red Sonya in “The Shadow of the Vulture.” Agnes is cut from similar cloth; but where these other women are all in stories with a male protagonist, Agnes is the protagonist and first-person narrator of her stories, and the only one of the four to appear in more than one tale. That allows her to take center stage much more obviously in the reader’s focus, and for Howard to develop her more as a character; in “Sword Woman,” he actually gives us her origin story, something he seldom if ever did for his other series characters.

Agnes was reared as a peasant in early 16th-century France, though her abusive father is the out-of-wedlock son of a duke (and uses his father’s name as a family name). In a vividly-sketched opening scene, that shows you exactly the kind of drudgery-filled bleakness her life up to then has been, when she’s about to be physically forced into an unwanted marriage to a youth she detests (and who knows that), her sister secretly hands her a dagger to commit suicide with. Instead, she uses it to knife her would-be groom/rapist, “with mad glee,” and takes to the woods. Circumstances soon give her the chance to get some combat training from a skilled mercenary, which she takes to like a fish to water, instinctively. With a tall physique strengthened by hard work, and quick reflexes, she’s a fighter to reckon with, and her embrace of that lifestyle is completely believable. She’s resolved to be no man’s sexual plaything; motherhood isn’t something she wants for herself; and the chance to be free, her own boss, and able to taste the world and its adventures is like a liberating new birth. (And she’ll have adventures in spades, with her share of dangerous enemies.)

Given her background, I could completely sympathize with the appeal this has for her, and understand her choices. I don’t think Howard intends to make an anti-marriage, anti-family statement through her, or to imply that her choice is the only legitimate one for a woman to make. But he does have the courage to portray her as the person she is, with legitimate reasons for feeling the way she does; and that he’s also questioning the kind of patriarchal, sexist perversions of marriage and family life that could turn those things into a prison (which they were never intended to be) for a woman, and make her willing to choose celibacy to escape it. And then too, he’s recognizing that the idea of “primitivism,” of escaping from society’s constraining rules, roles and routines, that leach every bit of freedom and spontaneity out of life, and being free to carve out your path in the world with your own courage and strength, is just as appealing to a woman as it is to a man, and for the same reasons.

If Howard had lived to write more about Agnes, and followed her for more of her life, who knows: she might someday have found a male who didn’t want to to imprison and dominate her, whom she might have wanted to be with as an equal, and might even have someday decided she was ready to have a child. (And if she had, I think she’d have been a doggone good mom!) But even if that had ever happened, you can bet she’d never have become any man’s slave or drudge.

All three stories exhibit the strengths Howard fans appreciate in his work: strong, exciting story-telling, full of adventure, suspense, and violent action, all of it well-drawn; excellent prose style; and good, vivid characterization. Agnes’ character, of course, dominates all three, and she’s one of Howard’s most memorable figures, round and nuanced. Like her sword-swinging soul-sisters mentioned above, she’s no choir girl, but she’s not evil in any sense. She doesn’t revel in killing (her “mad glee” near the beginning of the first story is an emotional reaction to the thrill of self-achieved deliverance and escape from hell on earth, not homicidal mania as such); on the contrary, she’s quite capable of showing mercy even when it’s not deserved, of genuine kindness to others, and of putting her life on the line even for an enemy. She’s a woman with principles; and while her early life has made her so emotionally repressed that she’s never been able to cry, she’s still got feelings, and can need comfort at times. (In other words, she’s a human being, not an animated stone statue of Superwoman.)

But several other characters are also developed with some moral complexity, especially Etienne Villiers. REH was also a serious student of history, and makes effective use of real historical persons and situations to flavor his historical fiction; these tales are no exception. In the third story, IMO, Page imitates Howard’s style and character conception quite well; I disagree strongly with critics like Jessica Salmonson who find the story inferior and see Agnes there as an unrecognizable, wimpy parody of herself. (If they weren’t dead by the time she’s done with them, there are a few male characters there who’d probably dispute the claim that she’s wimpy!

The editor of this collection isn’t named (Leigh Brackett contributes a worthwhile introduction, but I doubt if she was the editor), but whoever it was clearly just threw the last two selections in as filler to bulk up the book. They’d be better included in a collection of Howard fragments. The stories cited in the second paragraph above would have been better choices, IMO; then the collection would have been a genuinely thematic one showcasing all of Howard’s action heroines! Maybe some publisher will pick up on that idea?

Author: Robert E. Howard

Publisher: Zebra Books, available through Amazon, only in paperback.

A version of this review previously appeared on Goodreads.

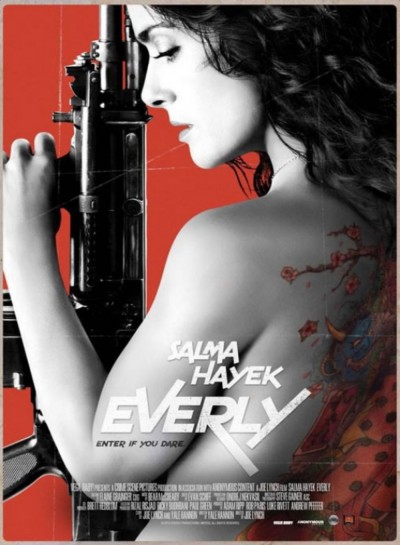

Not sure how this managed to escape attention in our 2015 preview, because it’s hard to think of a film more directly positioned in our wheel-house. This unfolds entirely in a single building, close to real time, the vast majority of it (as with 2LDK) in one apartment, where Everly (Hayek) has just been outed as betraying her boss, a ferociously vicious Japanese mobster called Taiko (Watanabe). Desperately, she calls her mother (Cepeda), begging her to take Everly’s daughter out of town, but when that route is closed, they’re forced to hide out with Everly in the apartment. It’s not much safer, for Taiko has offered a bounty to anyone in the building willing to take down his turncoat – and also some increasingly-deranged professionals. Meanwhile, we also find out more about Everly’s history, which includes four years trapped in the apartment building as a sex slave for Taiko and his cronies.

Not sure how this managed to escape attention in our 2015 preview, because it’s hard to think of a film more directly positioned in our wheel-house. This unfolds entirely in a single building, close to real time, the vast majority of it (as with 2LDK) in one apartment, where Everly (Hayek) has just been outed as betraying her boss, a ferociously vicious Japanese mobster called Taiko (Watanabe). Desperately, she calls her mother (Cepeda), begging her to take Everly’s daughter out of town, but when that route is closed, they’re forced to hide out with Everly in the apartment. It’s not much safer, for Taiko has offered a bounty to anyone in the building willing to take down his turncoat – and also some increasingly-deranged professionals. Meanwhile, we also find out more about Everly’s history, which includes four years trapped in the apartment building as a sex slave for Taiko and his cronies.

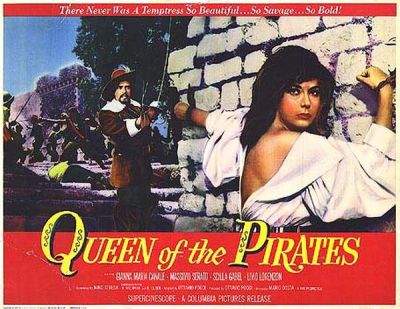

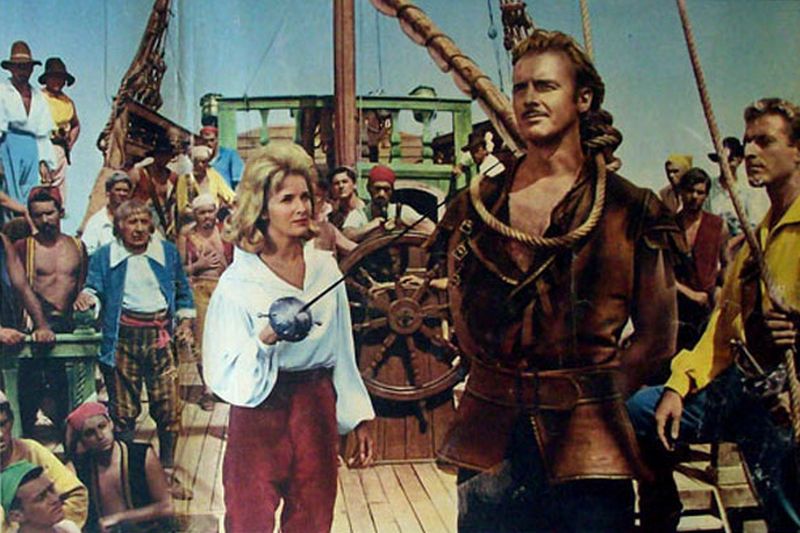

Sandra (Canale) and her father fall foul of the local tyrannical Duke (Muller) after they refuse to pay his excise duty. Arrested, the arrival of the poor but noble Count of Santa Croce, Cesare (Serato), saves them from death – or a fate worse than in Sandra’s case, as the Duke has a profitable sideline, shipping local girls off to the Middle East. After escaping, they join up with a local pirate band, who agree to help target the Duke after Sandra bests their leader in sword-play. To gain the hand of the duke’s daughter, Isabella (Gabel), Cesare agrees to hunt down the “Queen of the Pirates” who has brought trade to a standstill, not knowing that his target is the same woman he helped save, and since then has had a secret longing.

Sandra (Canale) and her father fall foul of the local tyrannical Duke (Muller) after they refuse to pay his excise duty. Arrested, the arrival of the poor but noble Count of Santa Croce, Cesare (Serato), saves them from death – or a fate worse than in Sandra’s case, as the Duke has a profitable sideline, shipping local girls off to the Middle East. After escaping, they join up with a local pirate band, who agree to help target the Duke after Sandra bests their leader in sword-play. To gain the hand of the duke’s daughter, Isabella (Gabel), Cesare agrees to hunt down the “Queen of the Pirates” who has brought trade to a standstill, not knowing that his target is the same woman he helped save, and since then has had a secret longing.

Despite its age – this was made in 1961 – it has stood the test of time fairly well, except for a romantic ending which is both predictable and unfortunate. This turns the heroine into exactly the subservient woman she spent the first 80 minutes

Despite its age – this was made in 1961 – it has stood the test of time fairly well, except for a romantic ending which is both predictable and unfortunate. This turns the heroine into exactly the subservient woman she spent the first 80 minutes