★

“Drop this connection.”

Dear lord, this is a chore. From an opening conversation which unfolds mainly in quotes from Gone With the Wind, Scarface and other, better movies, it was painfully obvious for what writer-director Patrick is aiming. This is supposed to be a Guy Ritchie-esque caper, in which a parade of quirky characters from the underworld jostle for possession of… something. Hilarity will surely ensue, as they trade foul-mouthed banter, get into and out of sticky situations and generally act in an amusingly inept manner. Except, hilarity most definitely does not ensue. I don’t think I broke into a smile once, with the whole concept being dead on arrival. Malta does look quite nice as a holiday destination though.

The heroine is agent Aureille Fleming (Coduri), though quite who she is an agent of, or why she is involved, never becomes particularly clear. The objects in question are some high denomination bearer bonds, and the film feels obligated to open with a caption explaining what these are. They have been stolen by a man known as The Priest, who flees from Ireland to Malta, and heavily-pregnant crime boss Alice (Spencer-Longhurst) wants them back. Everyone half-competent apparently being otherwise engaged, she sends hapless brother Rory (Robinson) and her husband Casper to the Mediterranean to retrieve them. Fleming – and, yes, it IS a painfully obvious 007 reference – is there to stop the bonds from falling into Alice’s hands, because… I don’t know. Maybe it was explained. I just don’t care.

At times this feels more like a fancy dress party than a film. People dressed up as nuns. People dressed up as clowns. People dressed as priests. This probably isn’t surprising, considering that it feels like Patrick is cosplaying as a film-maker. There’s little or no evidence to indicate he knows how to construct a coherent or interesting narrative. Instead, he proceeds by simply dropping in scenes which, I gueaa, are supposed to be “amusing”, without rhyme or reason. I called Aureille the heroine above, though there’s precious little to make her so. I presumed she is supposed to be the “good guy”, because there are no other credible candidates for that role, so she earns it by default.

At times this feels more like a fancy dress party than a film. People dressed up as nuns. People dressed up as clowns. People dressed as priests. This probably isn’t surprising, considering that it feels like Patrick is cosplaying as a film-maker. There’s little or no evidence to indicate he knows how to construct a coherent or interesting narrative. Instead, he proceeds by simply dropping in scenes which, I gueaa, are supposed to be “amusing”, without rhyme or reason. I called Aureille the heroine above, though there’s precious little to make her so. I presumed she is supposed to be the “good guy”, because there are no other credible candidates for that role, so she earns it by default.

I might have forgiven this had the action been up to a decent level. However, the cover is blatantly lying to us about this as well. I do not recall any moment at which she was on a motor-cycle, let alone wielding a gun. Admittedly, it’s possible my attention had wavered to such a degree I didn’t notice. I’m not sure I remember anyone being shot, and must have blinked and missed the helicopter. She throws a few lacklustre punches, and that’s close to the sum total of the action. A genuinely feeble excuse, it would not surprise me if this had been a tax write-off exercise. It’s the only way I can realistically explain the painful level on which this operates.

Dir: Danny Patrick

Star: Rosa Coduri, Flora Spencer-Longhurst, Jack Bence, Shane Robinson

I can’t recall seeing an action heroine movie with

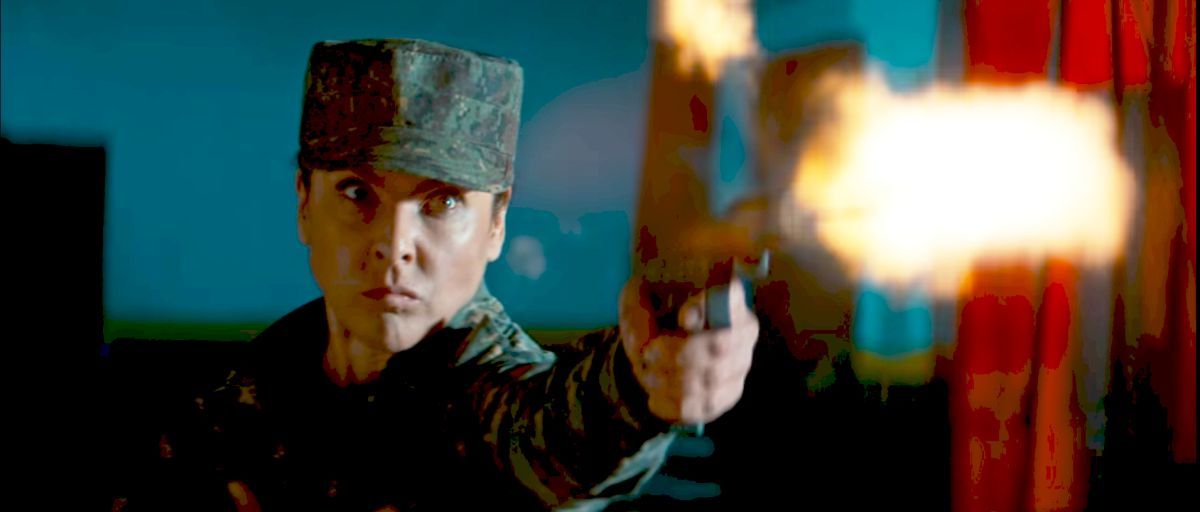

I can’t recall seeing an action heroine movie with  While technically solid, and occasionally looking quite good, this may be the laziest scripting I have seen in a movie for a long time. I feel I may have lost actual IQ points through the process of watching it, such is the degree of stupidity which this provides. The heroine is Mina (Black-D’Elia), a college student whose life is upended when she and her little sister narrowly escape a home invasion by Arab terrorists, in which both her parents are killed. She’s rescued by intelligence agent Olivia (Leonard), who tells her she’s the only heir of an Afghani warlord, Khalid (Arditti). Her mother betrayed him, and had to change her identity: he finally caught up with the family, and wants his daughter back.

While technically solid, and occasionally looking quite good, this may be the laziest scripting I have seen in a movie for a long time. I feel I may have lost actual IQ points through the process of watching it, such is the degree of stupidity which this provides. The heroine is Mina (Black-D’Elia), a college student whose life is upended when she and her little sister narrowly escape a home invasion by Arab terrorists, in which both her parents are killed. She’s rescued by intelligence agent Olivia (Leonard), who tells her she’s the only heir of an Afghani warlord, Khalid (Arditti). Her mother betrayed him, and had to change her identity: he finally caught up with the family, and wants his daughter back. I’m just going to begin by quoting the opening credit titles. Spelling, grammar and punctuation as received. “At the early stage of Republic of China, Yuan Hsi Hai wanted to rebel the democratic government & be the king. But there were 300,000 soldiers at Yuan Wan under the command of General Tsai obstructed his desire, so he cheated General Tsai to Peking & confined his movements. So Yuan who lived in Chu Jen Hall could fulfil his ambition but…” I reproduce this because, to a large extent, that’s everything I’ve got in terms of the over-arching plot here. It’s all about Tsai (Kwan) getting out of the city, in order to lead his troops and, presumably, frustrate Yuan’s dictatorial ambitions.

I’m just going to begin by quoting the opening credit titles. Spelling, grammar and punctuation as received. “At the early stage of Republic of China, Yuan Hsi Hai wanted to rebel the democratic government & be the king. But there were 300,000 soldiers at Yuan Wan under the command of General Tsai obstructed his desire, so he cheated General Tsai to Peking & confined his movements. So Yuan who lived in Chu Jen Hall could fulfil his ambition but…” I reproduce this because, to a large extent, that’s everything I’ve got in terms of the over-arching plot here. It’s all about Tsai (Kwan) getting out of the city, in order to lead his troops and, presumably, frustrate Yuan’s dictatorial ambitions. On the surface, Scala City is an idyllic, hi-tech world of prosperity, peace and morality, albeit at the cost of omnipresent surveillance of its residents. But there’s a dirty little secret. The Blind Spot is an area where surveillance is barred, and where the citizens of Scala City go to blow off their sordid steam. Its residents have cybernetically enhanced bodies, something rejected by Scala City, and a zero-tolerance policy for any kind of monitoring. It’s run by Wrench, who has kept his daughter Marcie Hugo under strict control since the death of her mother. However, like all teenagers, the 16-year-old Marcie is seeking to spread her wings, and has been making covert excursions into Scala City, with the aim of moving there some day soon.

On the surface, Scala City is an idyllic, hi-tech world of prosperity, peace and morality, albeit at the cost of omnipresent surveillance of its residents. But there’s a dirty little secret. The Blind Spot is an area where surveillance is barred, and where the citizens of Scala City go to blow off their sordid steam. Its residents have cybernetically enhanced bodies, something rejected by Scala City, and a zero-tolerance policy for any kind of monitoring. It’s run by Wrench, who has kept his daughter Marcie Hugo under strict control since the death of her mother. However, like all teenagers, the 16-year-old Marcie is seeking to spread her wings, and has been making covert excursions into Scala City, with the aim of moving there some day soon. Buffalo police officer Megan (Sadeghian) is a highly-skilled cop, but has a crisis of confidence after being involved in the accidental shooting of a colleague. To help get her out of that mindset, partner Jeremy (Johnson) invites Megan on a weekend camping getaway in upstate New York, along with another couple. This goes horribly wrong, after they stumble across the summary execution of a drug-dealer by the local sheriff, Preacher (Kennedy) and his death squad. The four campers are now a problem for Preacher, so he seals off the area, and unleashes a slew of hunters, putting a ten thousand dollar bounty on the head of each target. Of course, you don’t have to be psychic to see it won’t be easy, courtesy of Megan.

Buffalo police officer Megan (Sadeghian) is a highly-skilled cop, but has a crisis of confidence after being involved in the accidental shooting of a colleague. To help get her out of that mindset, partner Jeremy (Johnson) invites Megan on a weekend camping getaway in upstate New York, along with another couple. This goes horribly wrong, after they stumble across the summary execution of a drug-dealer by the local sheriff, Preacher (Kennedy) and his death squad. The four campers are now a problem for Preacher, so he seals off the area, and unleashes a slew of hunters, putting a ten thousand dollar bounty on the head of each target. Of course, you don’t have to be psychic to see it won’t be easy, courtesy of Megan. ★★★

★★★ There are quite a lot of familiar faces for this one. There’s the long-running relationship between Teresa and Russian mobster, Oleg Yosikov (Gil). This is somewhat reflected in the love triangle of her daughter, now very much her own young woman. Sofia has to decide between Oleg’s son, Fedor, and street-kid Mateo Mena. He rescues Sofia from a sticky situation, and those who want to use Sofia to force her mother into compliance with their wishes. There’s also faithful sidekick Batman, who has been with Teresa since the beginning. On the other side, as well as her ex-husband, whose power is now grown to such an extents as to be a real threat, there’s long-running DEA nemesis Ernie Palermo. He brought Teresa in, and is very keen for her to serve the rest of her eighty-five year prison sentence.

There are quite a lot of familiar faces for this one. There’s the long-running relationship between Teresa and Russian mobster, Oleg Yosikov (Gil). This is somewhat reflected in the love triangle of her daughter, now very much her own young woman. Sofia has to decide between Oleg’s son, Fedor, and street-kid Mateo Mena. He rescues Sofia from a sticky situation, and those who want to use Sofia to force her mother into compliance with their wishes. There’s also faithful sidekick Batman, who has been with Teresa since the beginning. On the other side, as well as her ex-husband, whose power is now grown to such an extents as to be a real threat, there’s long-running DEA nemesis Ernie Palermo. He brought Teresa in, and is very keen for her to serve the rest of her eighty-five year prison sentence.

Although almost a decade earlier than Lin Hsiao Lan’s slew of fantasy kung-fu flicks, this shares a lot of the same elements – not least an approach to narrative coherence best described as “informal.” This starts at the beginning, where we don’t even get introduced to the participants, before the martial arts breaks out. As we learn a little later, it turns out this pits Chu-Kwok Su-Lan (Shang-Kuan) against three members of the Devil’s Gang, in defense of her two, largely useless sidekicks. This is just the first of numerous encounters between our hero – yes, it’s

Although almost a decade earlier than Lin Hsiao Lan’s slew of fantasy kung-fu flicks, this shares a lot of the same elements – not least an approach to narrative coherence best described as “informal.” This starts at the beginning, where we don’t even get introduced to the participants, before the martial arts breaks out. As we learn a little later, it turns out this pits Chu-Kwok Su-Lan (Shang-Kuan) against three members of the Devil’s Gang, in defense of her two, largely useless sidekicks. This is just the first of numerous encounters between our hero – yes, it’s  Okay, I will admit that this strained credibility on a number of occasions, to the point that buttons were popping off its shirt. But I don’t think the makers were exactly going for gritty realism, and the bottom line is: I enjoyed this a lot. Certainly, more so than

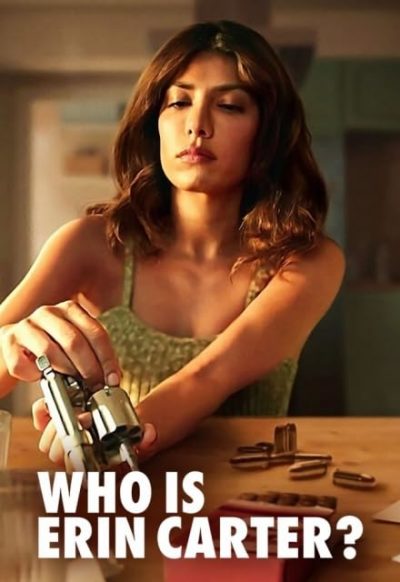

Okay, I will admit that this strained credibility on a number of occasions, to the point that buttons were popping off its shirt. But I don’t think the makers were exactly going for gritty realism, and the bottom line is: I enjoyed this a lot. Certainly, more so than  Turns out, Erin has a past, and the publicity resulting from her impromptu heroism brings it to visit. She finds herself embroiled in murder, organized crime and police corruption, as well as more normal familial drama, such as neighbourhood jealousy and whiny pre-teen nonsense. One of the seven 45-minute episodes is entirely in flashback (unexpected Jamie Bamber!), explaining the reason she changed her identity and moved to Spain, as well as why those from her history are keen to catch up with her. Even the spectacularly unobservant Jordi begins to realize that his other half is not quite as claimed. Her original explanation of a relapse into alcoholism doesn’t exactly explain all the sudden absences, injuries and unusual behaviour Erin is now exhibiting, as she tries to manage the escalating situation.

Turns out, Erin has a past, and the publicity resulting from her impromptu heroism brings it to visit. She finds herself embroiled in murder, organized crime and police corruption, as well as more normal familial drama, such as neighbourhood jealousy and whiny pre-teen nonsense. One of the seven 45-minute episodes is entirely in flashback (unexpected Jamie Bamber!), explaining the reason she changed her identity and moved to Spain, as well as why those from her history are keen to catch up with her. Even the spectacularly unobservant Jordi begins to realize that his other half is not quite as claimed. Her original explanation of a relapse into alcoholism doesn’t exactly explain all the sudden absences, injuries and unusual behaviour Erin is now exhibiting, as she tries to manage the escalating situation. Don’t mess with someone else’s dog. This is a good rule of thumb in most cases, but especially so when the owner is an unhinged teenage psychopath, with the both the talent and desire to inflict carnage in retribution. The

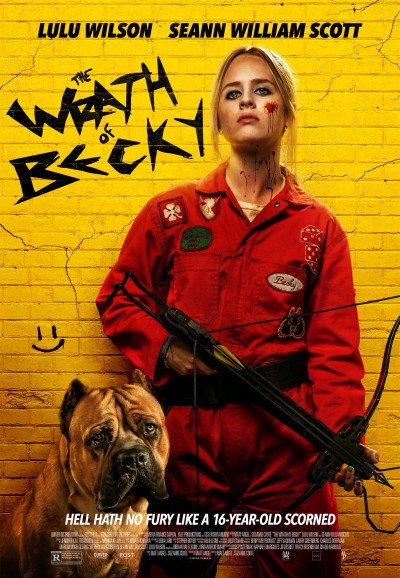

Don’t mess with someone else’s dog. This is a good rule of thumb in most cases, but especially so when the owner is an unhinged teenage psychopath, with the both the talent and desire to inflict carnage in retribution. The