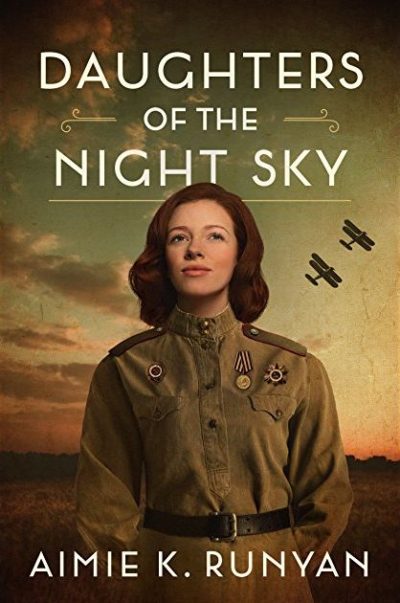

From left: Rufina Gasheva, Irina Sebrova, Natalia Meklin, Marina Chechneva, Nadezhda Popova, Seraphima Amosova, Evdokia Nikulina, Evdokia Bershanskaya, Maria Smirnova, Evgeniya Zhigulenko

[I covered the women tagged by their enemies as “Night Witches” – two years ago as part of our feature on Russian World War 2 women fighters. But having recently both read a book and watched a TV series about the exploits of these wartime flyers, it seemed appropriate to revisit the topic in some more depth.]

“We bombed, we killed; it was all a part of war. We had an enemy in front of us, and we had to prove that we were stronger and more prepared.”

— Nadezhda Popova, deputy commander, 588th

The regiment has its origins in October 1941, when Joseph Stalin signed Order number 0099, creating the 221st Aviation Corps: a group where women would not only be pilots, but engineers and ground support staff [men were later allowed in to fill some positions, though remained in a small minority]. His decision was in part due to a campaign by Marina Raskova, a noted aviator and friend of Stalin. She sought to take advantage of the high number of women with flight training, who had previously been barred from serving in the armed forces, except in ancillary roles.

The corps created by Stalin included two other regiments as well as the Night Witches. The 586th Fighter Aviation Regiment were first into combat, on April 16, 1942, and destroyed 38 enemy aircraft in 125 air battles. The 587th Bomber Aviation Regiment, commanded by Raskova until a plane crash took her life in January 1943, flew 1,134 missions, and dropped almost a thousand tons of bombs. But the one which achieved the biggest impact is the 588th Night Bomber Regiment.

Staffed with around 400 women, they received a brief but intensive course at the Engels Military Aviation School, before being deployed to the Eastern front where the Germans were advancing through the USSR, toward the end of May 1942. The lack of equipment intended for female use was problematic. Uniforms, for example, were hard to find in anything approaching the correct size, and often had to be modified by the recipient in order for them to fit.

The regiment’s aircraft were little better than hand-me-downs. They flew Polikarpov Po-2 biplanes, which were used more as training craft or crop dusters, and were incredibly slow, with a top speed of just 94 mph. But that became one of the regiment’s major advantages: the German planes were unable to fly at the Polikarpov’s speed, making it very difficult to shoot down [The aircraft is the only biplane with a documented jet “kill”: during the Korean War, a Lockheed F-94 Starfire stalled and crashed, while trying to engage one] Shooting down a Night Witch eventually became such a feat, it reportedly resulted in an automatic Iron Cross for the Luftwaffe pilot responsible.

“We were psychologically prepared to be killed. It was a tense situation all night. I told my co-pilot that no matter how terrible things got, to stay calm because I might need just one split second to do something to save our lives and if she shouted at me, we might lose that vital second.”

— Klavdia Deryabina

The low air-speed made them sitting ducks for ground fire, so the regiment flew at night. This wasn’t just safer, it made them into a psychological weapon, disrupting the enemy’s sleep as well as causing material damage with their bombs. The standard attack “involved flying only a few meters above the ground, rising for the final approach, throttling back the engine and making a gliding bombing run, leaving the targeted troops with only the eerie whistling of the wind in the wings’ bracing-wires as an indication of the impending attack.” Along with the female pilots, this sound, which the Germans likened to a broomstick, earned the regiment the nickname of Nachthexen, or “night witches.”

Their Polikarpovs had other limitations, too. As well as being dangerously flammable, every unnecessary item was removed to reduce weight and allow the aircraft to carry more bombs instead. The items stripped included radios, heaters for the open cockpits and even parachutes, so if the plane went down, so did the two-woman crew. They were still extremely limited in the munitions they could carry, so to make up for this, the planes made multiple sorties, returning to base and landing only for long enough to refuel and reload. The regiment’s deputy commander, Nadezhda Popova, flew eighteen bombing missions in one night.

We should not forget the work of the ground-staff: while less directly risky, their work was even more physically demanding, keeping the planes armed and able to fly. Senior mechanic Nina Karasyova-Buzina recounts, “Some nights we lifted 3,000 kilos of bombs. Three of us lifted the bombs, working together. We did our work at night and were not allowed to have any light to work by, so we worked blind, fumbling in darkness… We worked in mud, frost, sleet and water, and we were very precise in fixing the bombs. We had to work barehanded, so that we could feel what we were doing.”

In the early days, the regiment mostly operated in the Caucasus – not far from where the Amazons of Greek lore are believed to have lived. But as the German advance into Russia slowed, halted, and was eventually reversed, they were relocated to other theatres, including Byelorussia, Poland and Germany. They continued to fly right up until May 1945, when the Nazis surrendered, coming within 40 miles of Berlin. Disbanded that October, the Night Witches accumulated 28,676 flight hours, dropped over 3,000 tons of bombs and over 26,000 incendiary shells, damaging or completely destroying 17 river crossings, nine railways, two railway stations, 26 warehouses, 12 fuel depots, 176 armored cars, 86 firing points, and 11 searchlights.

Their efforts were not without cost. At its peak, the regiment had 40 two-person planes, but lost 31 members over the course of its missions, including one black night where four planes were lost, each with both of their crew. Many other members were shot down, some on multiple occasions, only to rejoin the regiment and continue flying. But their courage did not go unrecognized. Of the 95 women ever to receive the highest distinction awarded in the USSR, Hero of the Soviet Union, almost one-quarter (23) went to women who were part of the 588th. Ten of these women are shown below.

|

Nadezhda Popova

|

Natalya Meklin

|

Makuba Sirtlanova

|

Irina Sebrova

|

Antonina Khudyakova

|

|

Zoya Parfenova

|

Yevgeniya Rudneva

|

Tatyana Makarova

|

Olga Sanfirova

|

Nina Ulyanenko

|

“I knew the only way to survive was to be ice inside, to feel absolutely nothing.”

– Klavdiya Pankratova

After the war was over, the survivors of the 588th – or the 46th “Taman” Guards Night Bomber Aviation Regiment, as it had been renamed in honour of its role in two Soviet victories on the Taman Peninsula – returned to civilian life, though I’m sure this remained a defining experience in all their lives. Some stayed with aviation. Others became teachers. One, Yevgeniya Zhigulenko, became a film director, and made a movie about her experiences in 1981, In the Sky of the Night Witches. Members of the regiment were alive at least as recently as last year, when Evdokia Pasko passed away at the age of 98.

I don’t want to ignore the other two regiments, who have received less attention than the 588th – perhaps because both eventually became mixed-gender. The 586th Fighter Aviation Regiment was tasked with protecting ground-based targets from enemy attack. Among those who flew with the regiment at one point, were Lydia Litvyak and Yekaterina Budanova, the only two female fighter aces ever. The former, nicknamed the White Lily of Stalingrad, holds the all-time record, with twelve individual and four shared “kills” before her death in combat at the age of just 21. [She may well merit an entire article of her own down the road].

The 587th Bomber Aviation Regiment was renamed, in honor of its original commander and for its distinguished combat performance, to the 125th “M.M. Raskova” Guards Dive Bomber Regiment. During the war, five of its women in addition to Raskova became Heroes of the Soviet Union. As a sample of why, Klavdia Fomicheva’s bomber was hit by enemy fire on the way to its target, and the left engine went up in flames. She continued her mission, and dropped her bombs before turning back to friendly airspace, only bailing out after making sure her navigator had parachuted away. Despite suffering serious burns, Fomicheva was back the air barely three weeks later.

While these three regiments were the result of extraordinary circumstance and severe necessity, with every asset Russia possessed being pressed into service, it would be more than 50 years, in April 1993, before America would allow women pilots officially to fly any combat missions. Even setting aside the poor conditions, underwhelming equipment and the doubts of their superiors, it’s remarkable how far ahead of their time the Night Witches and their colleagues were.

Women pilots of the 586th fighter aviation regiment in 1942. From left Sergeant Lydia Litvyak, second Lieutenant Yekaterina Budanova and Lieutenant Maria Kuznetsova

There’a a good film in here. Actually, there may be as many as three good films in here. But the way in which they are melded together, manages to rob a good chunk of the power and impact from all of them. We begin by following Mathilde H (Bercot), a war journalist clearly modelled on Marie Colvin, down to the eye-patch and traumatic experience in Homs, Syria – Mathilde lost her eye there, Marie was killed. She has just started the process of embedding herself in Kurdistan, covering the locals’ attempt to regain territory taken from them by ISIS. The second story is that of Bahar (Farahani), leader of a Kurdish women’s battalion, who was forced to flee her hometown, losing her son in the process. She has heard rumours he is being radicalized and trained as a child soldier in occupied territory, and will risk anything to liberate him.

There’a a good film in here. Actually, there may be as many as three good films in here. But the way in which they are melded together, manages to rob a good chunk of the power and impact from all of them. We begin by following Mathilde H (Bercot), a war journalist clearly modelled on Marie Colvin, down to the eye-patch and traumatic experience in Homs, Syria – Mathilde lost her eye there, Marie was killed. She has just started the process of embedding herself in Kurdistan, covering the locals’ attempt to regain territory taken from them by ISIS. The second story is that of Bahar (Farahani), leader of a Kurdish women’s battalion, who was forced to flee her hometown, losing her son in the process. She has heard rumours he is being radicalized and trained as a child soldier in occupied territory, and will risk anything to liberate him.

I reviewed the

I reviewed the  While initially released as a film, what’s reviewed here is the extended cut, screened as four 45-minute episodes on Russia’s Channel One in May 2016. This is easily available, on both Amazon Prime and

While initially released as a film, what’s reviewed here is the extended cut, screened as four 45-minute episodes on Russia’s Channel One in May 2016. This is easily available, on both Amazon Prime and  It’s the summer of 1942, and Soviet forces are facing the invading German Army. After Sergeant Major Vaskov (Martynov) requests soldiers for his anti-aircraft battalion who won’t get drunk and molest the local women, he gets what he wants. Except, the new arrivals are an all-female squad of soldiers, with whom Vaskov is initially singularly ill-equipped to deal. However, they prove their mettle, led by the efforts of Rita Osyanina (Shevchuk), and eventually win Vaskov’s respect. While returning to the barracks one night, Rita stumbles across two Nazi paratroopers; she, along with four colleagues and Vaskov, form a search party, and head deep into the surrounding forest to capture the Germans. However, they discover the real force is significantly bigger, and must begin a guerilla warfare campaign to disrupt the enemy’s mission, harrying them through the wooded and marshy terrain.

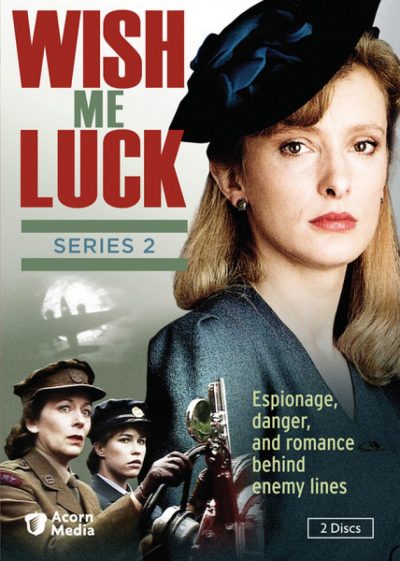

It’s the summer of 1942, and Soviet forces are facing the invading German Army. After Sergeant Major Vaskov (Martynov) requests soldiers for his anti-aircraft battalion who won’t get drunk and molest the local women, he gets what he wants. Except, the new arrivals are an all-female squad of soldiers, with whom Vaskov is initially singularly ill-equipped to deal. However, they prove their mettle, led by the efforts of Rita Osyanina (Shevchuk), and eventually win Vaskov’s respect. While returning to the barracks one night, Rita stumbles across two Nazi paratroopers; she, along with four colleagues and Vaskov, form a search party, and head deep into the surrounding forest to capture the Germans. However, they discover the real force is significantly bigger, and must begin a guerilla warfare campaign to disrupt the enemy’s mission, harrying them through the wooded and marshy terrain. This British TV series ran for three series from 1988 through 1990, with 23 episodes (each an hour long including commercials) in total. The same creators had previously been responsible for another WW2-based show, Tenko, about women in a Japanese prisoner-of-war camp after the fall of Singapore. The time period here is similar – the second half of World War 2 – but the focus moves from the Far East to Occupied Europe, in particular, France. At this point, the Allies were sending in agents to assist the local Resistance – and as

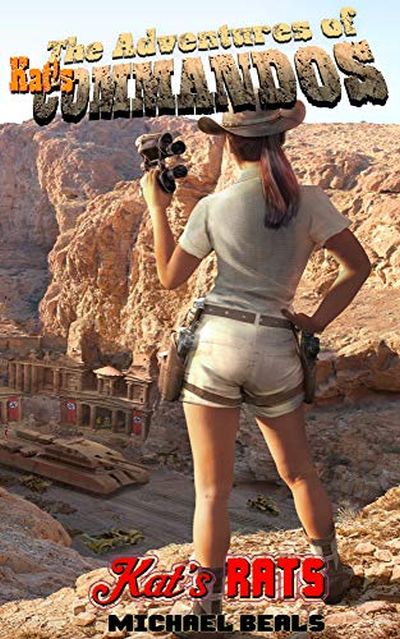

This British TV series ran for three series from 1988 through 1990, with 23 episodes (each an hour long including commercials) in total. The same creators had previously been responsible for another WW2-based show, Tenko, about women in a Japanese prisoner-of-war camp after the fall of Singapore. The time period here is similar – the second half of World War 2 – but the focus moves from the Far East to Occupied Europe, in particular, France. At this point, the Allies were sending in agents to assist the local Resistance – and as  Katelyn Wolfraum is a German expat, who was working as a field agent for MI-6, until an unfortunate incident just before the war, involving a member of the British Royal Family, left her persona non grata with the authorities. Fast forward to 1941, the depths of World War II, and she’s an intelligence analyst under Colonel Lyons and Major Trufflefoot in the North African desert. With Field-Marshall Rommel tearing across the terrain in a blitzkrieg, she finds herself trapped deep behind enemy lines, along with a motley international band of Allied soldiers. When they discover evidence of a Nazi super-weapon about to be deployed, Kat and her colleagues decide to take the fight to the enemy and sabotage the Third Reich’s plans. But complicating matters is the presence of Kat’s foster father, who is now a high-ranking officer in the SS, tasked with ensuring the saboteurs are stopped.

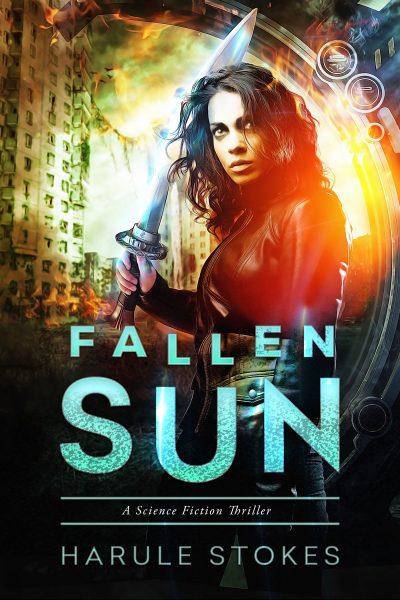

Katelyn Wolfraum is a German expat, who was working as a field agent for MI-6, until an unfortunate incident just before the war, involving a member of the British Royal Family, left her persona non grata with the authorities. Fast forward to 1941, the depths of World War II, and she’s an intelligence analyst under Colonel Lyons and Major Trufflefoot in the North African desert. With Field-Marshall Rommel tearing across the terrain in a blitzkrieg, she finds herself trapped deep behind enemy lines, along with a motley international band of Allied soldiers. When they discover evidence of a Nazi super-weapon about to be deployed, Kat and her colleagues decide to take the fight to the enemy and sabotage the Third Reich’s plans. But complicating matters is the presence of Kat’s foster father, who is now a high-ranking officer in the SS, tasked with ensuring the saboteurs are stopped. While not perfect, I think this one will probably end up sticking in my mind longer than most of the books I read. For one, it helps being a stand-alone and complete work, rather than the first of a multi-volume set. While I understand the rationale behind the latter – that’s where the bread and butter of writing income is made – it was refreshing to get a beginning, middle and proper end, without a cliff-hanger or opening for sequels. It was also different in content, rather than being yet another book which drops fantasy creatures like elves or vampires in a contemporary setting. I’ve seen enough of those this year, thankyouverymuch.

While not perfect, I think this one will probably end up sticking in my mind longer than most of the books I read. For one, it helps being a stand-alone and complete work, rather than the first of a multi-volume set. While I understand the rationale behind the latter – that’s where the bread and butter of writing income is made – it was refreshing to get a beginning, middle and proper end, without a cliff-hanger or opening for sequels. It was also different in content, rather than being yet another book which drops fantasy creatures like elves or vampires in a contemporary setting. I’ve seen enough of those this year, thankyouverymuch. In September 1941, the author returns to Manila, the capital of the Philippines, starting work as a nightclub singer and falls in love with American GI, John Phillips. Which is unfortunate timing, because soon after, the Japanese bomb Pearl Harbor, kicking off the war in the Pacific. A hasty marriage to John follows on Christmas Eve, but Japan invades, and Claire’s husband becomes a prisoner of war. Left to fend for herself, after a period spent hiding out in the countryside, she returns to Manila, adopting the persona of Dorothy Fuentes, born in the Philippines of Italian parents. In order to help the resistance, she opens a venue, Club Tsubaki, aimed at officers of the occupying forces.

In September 1941, the author returns to Manila, the capital of the Philippines, starting work as a nightclub singer and falls in love with American GI, John Phillips. Which is unfortunate timing, because soon after, the Japanese bomb Pearl Harbor, kicking off the war in the Pacific. A hasty marriage to John follows on Christmas Eve, but Japan invades, and Claire’s husband becomes a prisoner of war. Left to fend for herself, after a period spent hiding out in the countryside, she returns to Manila, adopting the persona of Dorothy Fuentes, born in the Philippines of Italian parents. In order to help the resistance, she opens a venue, Club Tsubaki, aimed at officers of the occupying forces.

No army in recent military history has made more use of women than the Soviets during World War 2. As we’ve

No army in recent military history has made more use of women than the Soviets during World War 2. As we’ve