Literary rating: ★★★★★

Kick-butt quotient: ☆☆☆

Lance Charnes and I are Goodreads friends, having “met” (electronically) a few years ago through the Action Heroine Fans group. Some time ago, I bought a copy of his outstanding debut novel, Doha 12, and it got five stars from me. This new novel, the opener for a projected series, didn’t come to me as an official review copy –instead, Lance generously donated a print copy to the library where I work– but he knew I would read and review it, and knew my tastes well enough to be pretty sure I’d like it. Of course, we both understood that he might be wrong –but he wasn’t! For much of my reading experience, I expected to rate the book four stars –a denouement and conclusion that blew me to pieces and then knit me back together easily pushed it up to five stars.

Lance Charnes and I are Goodreads friends, having “met” (electronically) a few years ago through the Action Heroine Fans group. Some time ago, I bought a copy of his outstanding debut novel, Doha 12, and it got five stars from me. This new novel, the opener for a projected series, didn’t come to me as an official review copy –instead, Lance generously donated a print copy to the library where I work– but he knew I would read and review it, and knew my tastes well enough to be pretty sure I’d like it. Of course, we both understood that he might be wrong –but he wasn’t! For much of my reading experience, I expected to rate the book four stars –a denouement and conclusion that blew me to pieces and then knit me back together easily pushed it up to five stars.

Being his Goodreads friend, I try to keep abreast of Lance’s book reviews, so I know firsthand how well read he is in the whole area of the contemporary fine arts market, and particularly of its increasingly seedy underbelly. In real life, art by big-name artists can command staggering prices, and in the last 15-20 years it’s come to be a major commodity in the world of big-time international money laundering and shady commercial exchanges where cash transfers come too easily to the attention of authorities. And a lot of art that’s traded this way may be stolen, or forged.

Rich collectors with an enthusiasm for art aren’t the only players any more; we’re dealing with crime syndicates, corrupt and despotic governments and their officials, and billionaires looking for ways to cheat the tax authorities, and violence and murder may be aspects of normal business operations for some of these people. Lance sets this novel in that milieu, and he and his protagonist Matt Friedrich know it like the back of their hand. The author is also well-traveled; he sets his tale mostly in Europe, and principally Milan, and brings the locale to life with an assurance and level of detail which suggests he’s actually been there, or researched it a LOT online.

This is crime fiction more than traditional mystery; and as in his debut novel, Lance uses the knowledge of skulduggery, weapons, and high-technology snooping gained as a military intelligence officer to good advantage. The plotting is taut (first-person, present-tense narration is used for maximum immediacy) and the pace brisk, with a steady dose of dangerous situations and life-threatening tension. Matt’s crafty scheming sometimes takes the reader by surprise, and he’s sometime majorly taken for surprise himself, along with the reader. Action scenes aren’t frequent, but you never know when they could erupt, and when they do they’re well depicted. I’ve used the term “thriller” for this book, and that’s one I seldom use; I don’t seek out books that bill themselves that way, because I think the plotting is usually so cliched and stereotyped that it fails to thrill. This one doesn’t fail.

I’ve also used the term “gritty.” As described above, the moral world of this novel is a dark one where people are generally guided by the most selfish and cynical of motives, where the law is typically powerless to do much, and where innocent people are hurt as a by-product of what some of the characters routinely do. The DeWitt so-called “Agency” is a morally ambiguous enterprise that works for the highest bidder, and our narrator is an ex-con who was once involved in crooked art deals, and is now so crushed under a mountain of legal debts that he’s willing to violate his parole by working for said agency if it gives him a shot at paying it down.

And yet this is a surprisingly (or perhaps not surprisingly, given the moral vision that animates the author’s earlier novel) moral work of fiction, with a main character who’s learned something about life and ethics from his time in prison, and who wants to become a human being that he can look in the mirror and respect. He’s going to encounter challenges and decisions here that will put that resolve to the test. Both Matt and Carson (the female operative he’s paired with –who provides the team’s muscles and fighting skill when it’s needed) are intensely vital, round, realistic characters with a credible pattern of interactions that doesn’t stay static, but develops believably. Unlike some writers of this type of fiction, Lance understands that characters you care about are the only thing that can truly provide it with its heart, and he gives character development and relationships their due. There’s a lot that I can’t tell you because I’m determined to avoid spoilers; but I can say that this is where the book really earns its stars. (The principal supporting characters are masterfully drawn as well.)

You don’t have to be familiar with the world of the contemporary art market to enjoy this book (I’m not, at all); the author explains everything you have to know, and he does it easily and smoothly, in small doses with no info-dumps. None of the discussion is detailed enough to be boring. He uses enough physical description to let you visualize scenes, but not, IMO, too much; the same with technological exposition. (At one point, I didn’t really understand what one of the villains was trying to gain by his conduct; but the narrative drive carried me through without asking questions.) f you’re any kind of fan of crime fiction thrillers in a contemporary setting, and my review intrigues you rather than turning you away, I’d say this is definitely worth your checking out. I’m certainly going to be following the series; and I’m now even more anxious to read the author’s South, sooner rather than later!

Matt’s very sensible to feminine charms (he hasn’t been out of prison very long), but there’s no sex here, and Matt actually refrains from taking sexual advantage of one young woman. Violence isn’t any more frequent or graphic than it needs to be. As for bad language, not all of the characters swear, but some do, including Matt; Carson and one of the villains have the worst mouths (including the f-word as regular vocabulary). I never felt that the author was trying to mainstream that kind of thing, nor push the envelope with it.

Author: Lance Charnes

Publisher: Wombat Group Media, available through Amazon, both for Kindle and as a printed book.

A version of this review previously appeared on Goodreads.

This is likely the kind of book you enjoy rather than appreciate. While no-one will ever mistake this for great literature – you could go with “ludicrous nonsense,” and I’d not argue much – it’s a fun enough bit of pulp fiction that I kept turning the pages.

This is likely the kind of book you enjoy rather than appreciate. While no-one will ever mistake this for great literature – you could go with “ludicrous nonsense,” and I’d not argue much – it’s a fun enough bit of pulp fiction that I kept turning the pages.  This self-published novel was recently donated by the author to the library where I work, a kindness that we appreciate. The author and I are both members of the Action Heroine Fans group here on Goodreads, and I was intrigued by his posts there about the book. Understanding (from experience!) the frustrations of waiting for reviews in today’s glutted book market, and being a fan of kick-butt female protagonists myself, I’d hoped to help him out with a good review, though he didn’t donate the book with any such expectation. As my rating indicates, my reaction wasn’t as positive as I’d hoped, so I would have refrained from writing a review at all; but Tom graciously indicated that he didn’t have a problem with a less than stellar review.

This self-published novel was recently donated by the author to the library where I work, a kindness that we appreciate. The author and I are both members of the Action Heroine Fans group here on Goodreads, and I was intrigued by his posts there about the book. Understanding (from experience!) the frustrations of waiting for reviews in today’s glutted book market, and being a fan of kick-butt female protagonists myself, I’d hoped to help him out with a good review, though he didn’t donate the book with any such expectation. As my rating indicates, my reaction wasn’t as positive as I’d hoped, so I would have refrained from writing a review at all; but Tom graciously indicated that he didn’t have a problem with a less than stellar review. Shanti is a bad-ass. Not that you’d know it when we first encounter her, staggering through the wilderness on the edge of death, after an ill-considered choice of route as she escapes from… Something. We’ll get back to that. Fortunately, she is found by Sanders, a career soldier from a nearby city, out on a training mission with a band of raw recruits. They take her back to their town, where she’s nursed back to health – then the awkward questions begin, concerning where she was going and precisely why she was carrying weapons. But the key turns out to be Captain Cayan, who possesses the same psionic warfare capabilities as Shanti; except, he’s all but unaware of it, a sharp contrast to her finely-honed and practiced expertise.

Shanti is a bad-ass. Not that you’d know it when we first encounter her, staggering through the wilderness on the edge of death, after an ill-considered choice of route as she escapes from… Something. We’ll get back to that. Fortunately, she is found by Sanders, a career soldier from a nearby city, out on a training mission with a band of raw recruits. They take her back to their town, where she’s nursed back to health – then the awkward questions begin, concerning where she was going and precisely why she was carrying weapons. But the key turns out to be Captain Cayan, who possesses the same psionic warfare capabilities as Shanti; except, he’s all but unaware of it, a sharp contrast to her finely-honed and practiced expertise. I think it’s the “poorly written” aspect which I find most offensive. For I’m entirely down for some good ol’ entertainment in the form of justified violence, from Dirty Harry through Ms. 45 to Starship Troopers. But this… Oh, dear. The most stunning thing was discovering that this was the first in a series of twenty-seven novels in the “Sisterhood” series. Twenty-seven. I guess this proves there’s a market for this kind of thing, though I am completely at a loss as to who it might be. It certainly isn’t me.

I think it’s the “poorly written” aspect which I find most offensive. For I’m entirely down for some good ol’ entertainment in the form of justified violence, from Dirty Harry through Ms. 45 to Starship Troopers. But this… Oh, dear. The most stunning thing was discovering that this was the first in a series of twenty-seven novels in the “Sisterhood” series. Twenty-seven. I guess this proves there’s a market for this kind of thing, though I am completely at a loss as to who it might be. It certainly isn’t me. I initially thought I had a fairly good handle on where the first book in the Immortal Vegas series (currently at six entries, plus a prequel) was going, with a Lara Croft-esque lead, who specializes in locating and recovering ancient artifacts. You can also throw in fragments of The Da Vinci Code, since she is hired to retrieve a relic from the secret basement beneath the Vatican, and is going up against a cult of religious, Catholic fanatics. But it somehow ends up taking a sharp right-turn, ending up in a version of Las Vegas where, just out of phase with the casinos and hotels, lurks a hidden dimension of other venues, populated by…

I initially thought I had a fairly good handle on where the first book in the Immortal Vegas series (currently at six entries, plus a prequel) was going, with a Lara Croft-esque lead, who specializes in locating and recovering ancient artifacts. You can also throw in fragments of The Da Vinci Code, since she is hired to retrieve a relic from the secret basement beneath the Vatican, and is going up against a cult of religious, Catholic fanatics. But it somehow ends up taking a sharp right-turn, ending up in a version of Las Vegas where, just out of phase with the casinos and hotels, lurks a hidden dimension of other venues, populated by… In the 10th century B.C., the kingdom of Sheba (or Saba –the S and Sh sounds were still fluid in the Semitic alphabets of that day) straddled the Arabic and African sides of the southern entrance to the Red Sea, and enjoyed considerable income from its control of that trade route. Both the Old Testament books of I Kings and II Chronicles record a state visit by the Queen of Sheba to King Solomon. Neither of these writers record her name (it varies in the legends, but the most common name given is Balkis or Belkis –English transliterations vary) or much about her, and written records from Sheba at this time have not survived; but she’s also mentioned in the Koran. Jewish, Arabic and Ethiopian legends (the latter written down in the ancient writing Kebra Negast, or “Glory of Kings”) some of which probably preserve actual handed-down oral history, greatly elaborate the story, and the latter makes Solomon out to be the father of her son and heir, Menelik. (The royal house of Ethiopia historically claimed descent from Solomon through Menelik.) The legends of the Masai and other African peoples south of Ethiopia also credit Menelik with a great (and obviously historically memorable) expedition through their territories. This real-life material provides the basis for Jade del Cameron’s fifth adventure.

In the 10th century B.C., the kingdom of Sheba (or Saba –the S and Sh sounds were still fluid in the Semitic alphabets of that day) straddled the Arabic and African sides of the southern entrance to the Red Sea, and enjoyed considerable income from its control of that trade route. Both the Old Testament books of I Kings and II Chronicles record a state visit by the Queen of Sheba to King Solomon. Neither of these writers record her name (it varies in the legends, but the most common name given is Balkis or Belkis –English transliterations vary) or much about her, and written records from Sheba at this time have not survived; but she’s also mentioned in the Koran. Jewish, Arabic and Ethiopian legends (the latter written down in the ancient writing Kebra Negast, or “Glory of Kings”) some of which probably preserve actual handed-down oral history, greatly elaborate the story, and the latter makes Solomon out to be the father of her son and heir, Menelik. (The royal house of Ethiopia historically claimed descent from Solomon through Menelik.) The legends of the Masai and other African peoples south of Ethiopia also credit Menelik with a great (and obviously historically memorable) expedition through their territories. This real-life material provides the basis for Jade del Cameron’s fifth adventure. This is set in a world where various kinds of magic exist, alongside humans. The former include shapeshifters, vampires, faes (fairies), mages and the despised “Legacies”. The last-named cover the heroine, Levy Michaels, and that’s a bit of a problem. The reason for the hate, is because some of her kind were responsible, in previous generations, for a very nasty bit of spellcasting called “The Cleanse”; it was basically intended to cause occult genocide, and only narrowly avoided. Since then, Legacies have been harried and hunted by the other kinds. Levy’s late parents taught her to hide her abilities and pass as human, and she does so now, albeit occasionally having to handle those who track her down.

This is set in a world where various kinds of magic exist, alongside humans. The former include shapeshifters, vampires, faes (fairies), mages and the despised “Legacies”. The last-named cover the heroine, Levy Michaels, and that’s a bit of a problem. The reason for the hate, is because some of her kind were responsible, in previous generations, for a very nasty bit of spellcasting called “The Cleanse”; it was basically intended to cause occult genocide, and only narrowly avoided. Since then, Legacies have been harried and hunted by the other kinds. Levy’s late parents taught her to hide her abilities and pass as human, and she does so now, albeit occasionally having to handle those who track her down.

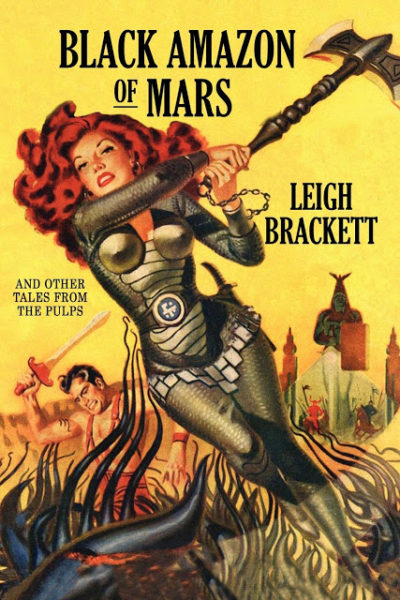

Normally, I like to start a series at the beginning. But I chose to read this second novella of Brackett’s Eric John Stark series, as my long-awaited first introduction to her work, because Amazon offered me the chance to read it for free on my Kindle app. (And yes, I’ll definitely be buying a paper copy!) That means there are unanswered questions here about Stark’s origins and background, and about the Martian world –what kind of “beasts” are used as mounts here, for instance, or what the economic base of a city-state like Kushat is– that probably have answers in the first book, or earlier stories. (The author wrote about the character in both formats, and not all of the corpus is still in print.)

Normally, I like to start a series at the beginning. But I chose to read this second novella of Brackett’s Eric John Stark series, as my long-awaited first introduction to her work, because Amazon offered me the chance to read it for free on my Kindle app. (And yes, I’ll definitely be buying a paper copy!) That means there are unanswered questions here about Stark’s origins and background, and about the Martian world –what kind of “beasts” are used as mounts here, for instance, or what the economic base of a city-state like Kushat is– that probably have answers in the first book, or earlier stories. (The author wrote about the character in both formats, and not all of the corpus is still in print.)