Literary rating: ★★★★★

Kick-butt quotient: ☆☆

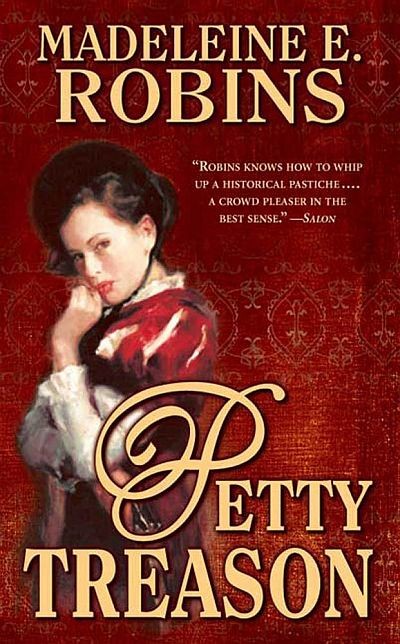

This second volume of Robins’ high-quality Sarah Tolerance series has much in common with the first book, (Point of Honour, which I’ve already reviewed here) in style and literary strong points; and of course it shares a protagonist and other continuing characters (and an ethos) with its predecessor, and builds on the premise and events laid out there. While it could be read first and still be enjoyed, IMO the series should be read in order to fully understand the characters and relationships (and Sarah’s unique situation), and appreciate their development here.

This second volume of Robins’ high-quality Sarah Tolerance series has much in common with the first book, (Point of Honour, which I’ve already reviewed here) in style and literary strong points; and of course it shares a protagonist and other continuing characters (and an ethos) with its predecessor, and builds on the premise and events laid out there. While it could be read first and still be enjoyed, IMO the series should be read in order to fully understand the characters and relationships (and Sarah’s unique situation), and appreciate their development here.

Six months have passed since the events of Point of Honor; we’re now in November, 1810. In the background, the Napoleonic Wars still drag on, with widespread dissatisfaction on the home front with the sacrifices the government demands to support and provision the troops abroad; and Queen Charlotte’s poor health fuels the poisonous infighting of Whig and Tory factions as they jockey for the possible appointment of a new regent. The book’s cover copy gives a basically accurate explanation of the case confronting Sarah here –except that this is actually NOT a locked room mystery, classic or otherwise; whoever wrote the description didn’t read the book carefully. It’s not her usual type of investigation, and she undertakes it reluctantly; she’s accustomed to inquire after lost articles, errant spouses, social skeletons in the closet, etc –not to track down murderers. But the events of the previous book have demonstrated that she can do the latter; and since the investigating authorities are inclined to pin this crime on the widow, her brother believes that hiring Sarah might be his desperate last chance to find the real culprit and clear his sister.

Robins has crafted a challenging mystery that will satisfy genre fans, and keep them guessing down to the wire; the deceased had secrets that don’t immediately meet the eye, and he wasn’t the only one with things to hide. The pace of the storytelling and investigating is slow, in keeping with transportation by foot or by horse and communication by written messages; we see investigation conducted as it actually would be in this cultural context and with this kind of technology (or lack of technology). We’re also immersed very much in the daily life of a young woman in the Regency world; the way the author brings the milieu to life is a great strength of the series.

That said, the action component here is significantly greater than it was in the first book, reflected in the kick-butt quotient above, which here goes up a star. There’s also much less in the way of actual sexual situations, though Sarah still lives out back of her aunt’s high-society brothel and is close friends with a prostitute, and though her inquiries here will expose her to the ugly world of sexual sadism, where some brothels called “birching houses” cater to the tastes of males who get sexual satisfaction from beating and brutalizing women. As in the first book, there’s not much bad language here; low-life characters use the f-word three times, but in a context where it’s actually the Anglo-Saxon verb these people would use (rather than as an all-purpose expletive, as we hear it nowadays).

Sound historical research underlies the story here, as Robins makes clear in her appended “History and Appreciation.” The details of English criminal law of that day, as given in the book, are accurate; and the attempt to kill one of the king’s sons, the Duke of Cumberland, by his valet Sallis (who committed suicide when it failed) really did take place in May 1810. (In her alternate world here, Robins took the liberty of moving it to August.) And Cumberland actually was, as here, a scandal-ridden High Tory who wasn’t much loved by the populace. An equalitarian feminist subtext set against the backdrop of a very chauvinistic society (and ours really isn’t much less so, though we’re more hypocritical about it) is another strong point here.

Sarah’s a great heroine, who readily earns this reader’s respect and admiration. The snobbier members of Regency High Society don’t consider her a “lady” (and she doesn’t claim to be), and think an unwise choice made in the passion of teenage love should forever brand her as a moral pariah. But most readers will recognize her as a lady, and a classy one, with a very solid moral compass and integrity. And as the best literature always does, this novel focuses on very real moral choices, that will further temper the precious metal of her integrity in a crucible.

There’s no second-in-the-series slump here; if anything, I actually liked this novel even better than the first one! Next year, I’m hoping to read the third installment of the series, The Sleeping Partner.

Author: Madeleine E. Robins

Publisher: Tor, available through Amazon, both for Kindle and as a printed book.

A version of this review previously appeared on Goodreads.