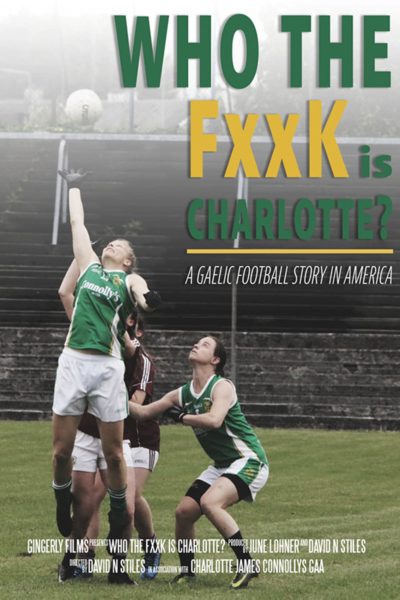

★★★★

“When Irish eyes are smiling.”

I stumbled across this entirely by accident, Tubi’s autoplay feature putting it on after watching some World Cup highlights. But the start was intriguing enough to keep me watching, and turned out to be a really good documentary, even if the story is a bit clichéd. The original title was the rather more forthright, Who the Fxxk is Charlotte? and that sums up the approach here. Any viewers with an aversion to strong language should not apply. It’s the story of the Charlotte, North Carolina women’s Gaelic football team, and their quest to win the national title. Gaelic football? Yes: an Irish sport, which combines elements of football and rugby. In Ireland, it’s close to a religion with fierce rivalries that go back to the 19th century.

I stumbled across this entirely by accident, Tubi’s autoplay feature putting it on after watching some World Cup highlights. But the start was intriguing enough to keep me watching, and turned out to be a really good documentary, even if the story is a bit clichéd. The original title was the rather more forthright, Who the Fxxk is Charlotte? and that sums up the approach here. Any viewers with an aversion to strong language should not apply. It’s the story of the Charlotte, North Carolina women’s Gaelic football team, and their quest to win the national title. Gaelic football? Yes: an Irish sport, which combines elements of football and rugby. In Ireland, it’s close to a religion with fierce rivalries that go back to the 19th century.

The Charlotte club was formed in 2000, and based on what we see here, is as much a social organization as a sports club. There does appear to be quite a lot of consumption of adult beverages. But there’s no doubt, they take the sport seriously, and recruit from all round the area, both Irish and American players. On North America, teams can bring in experienced players from Ireland, known as “sanctions”, to help grow the sport. But some clubs do that to excess: Charlotte refuse to go that route, putting their team at a potential disadvantage compared to Boston, or their arch-rivals from San Francisco, the Fog City Harps. The film follows Charlotte as they develop their team, and take part in the 2016 and 2017 senior women’s tournament, for the best sides in North America.

The Charlotte club was formed in 2000, and based on what we see here, is as much a social organization as a sports club. There does appear to be quite a lot of consumption of adult beverages. But there’s no doubt, they take the sport seriously, and recruit from all round the area, both Irish and American players. On North America, teams can bring in experienced players from Ireland, known as “sanctions”, to help grow the sport. But some clubs do that to excess: Charlotte refuse to go that route, putting their team at a potential disadvantage compared to Boston, or their arch-rivals from San Francisco, the Fog City Harps. The film follows Charlotte as they develop their team, and take part in the 2016 and 2017 senior women’s tournament, for the best sides in North America.

There are absolutely no pretensions here. It’s a very straightforward approach, and that no-nonsense style fits the participants to a T. Unlike some docs, there’s no off-field drama here, be it artificial or genuine. It’s all about the sport, and it’s depicted as a classic underdog story with plucky Charlotte trying to beat their larger, more established and more “sanctiony” opponents. Though in regard to the last, I would have been curious to see actual numbers: how many of their team were Americans, and how does that compare, say, to the Harps? It’s an easy enough sport to pick up for a viewer, though in some of the games, it was occasionally hard to know the exact score. A score bug in the corner would have been useful.

In some ways, the structure feels like it mirrors that of a classic kung-fu film. The heroine loses the first battle against her nemesis, but this only increases her resolve. She withdraws, trains harder and learns new techniques, in order to prepare for the rematch. That’s what we have here, with the 2016 tournament ending in defeat. The Charlotte coach also retires, his previously pledged three-year term having come to a close. Yet this opens the door for a dual-headed approach, with two managers of different styles. Considering this is a sport about which I knew almost nothing going in, it was all remarkably engrossing. If you’re not cheering by the end, you’ve clearly got no Irish in you.

Dir: David N. Stiles

Star: Aoife Kavanagh, Catríona O’Shaughnessy, Jan Henry, Kevin Tobin

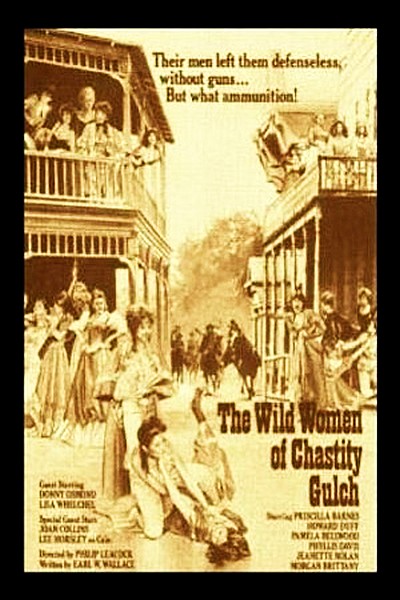

This sprightly TV movie from 1982 boasts a rather decent cast and, at least in the first half, manages to go in unexpected and interesting direction. It does end up descending into rather familiar territory thereafter, and the finale doesn’t manage to be as rousing as it should be. Yet it managed to keep my interest, and as this genre goes, that probably makes it better than average. It takes place in the last stages of the American Civil War, when the Southern women of Sweetwater have been left bereft of men, after the Confederate Army has recruited them all to their cause. Newly arrived in town is doctor Maggie McCulloch (Barnes), who has arrived to help her ailing aunt, Annie (Collins). She is shocked to discover Annie is less the mine owner touted in her letters, and more the owner of the town brothel.

This sprightly TV movie from 1982 boasts a rather decent cast and, at least in the first half, manages to go in unexpected and interesting direction. It does end up descending into rather familiar territory thereafter, and the finale doesn’t manage to be as rousing as it should be. Yet it managed to keep my interest, and as this genre goes, that probably makes it better than average. It takes place in the last stages of the American Civil War, when the Southern women of Sweetwater have been left bereft of men, after the Confederate Army has recruited them all to their cause. Newly arrived in town is doctor Maggie McCulloch (Barnes), who has arrived to help her ailing aunt, Annie (Collins). She is shocked to discover Annie is less the mine owner touted in her letters, and more the owner of the town brothel. That aside, the plot unfolds largely as you’d expect. There’s the initial tension between whores and housewives, and the women struggle to come to terms with the everyday business of running the town. For example, there’s a fire drill, which ends up with half the ladies thrashing around in shallow water, and some other slapstick involving whitewash, that is somewhere between lightly amusing and embarrassing. However, Barnes – at the time a sitcom star in Three’s Company – does a very good job of keeping the film grounded, and the supporting cast help admirably in that aspect. Collins is particularly good, projecting an attitude which clearly proclaims she will take no shit from anyone.

That aside, the plot unfolds largely as you’d expect. There’s the initial tension between whores and housewives, and the women struggle to come to terms with the everyday business of running the town. For example, there’s a fire drill, which ends up with half the ladies thrashing around in shallow water, and some other slapstick involving whitewash, that is somewhere between lightly amusing and embarrassing. However, Barnes – at the time a sitcom star in Three’s Company – does a very good job of keeping the film grounded, and the supporting cast help admirably in that aspect. Collins is particularly good, projecting an attitude which clearly proclaims she will take no shit from anyone. This showed up as a bit of a surprise. Obviously, even the title suggested that the makers were looking for a sequel to

This showed up as a bit of a surprise. Obviously, even the title suggested that the makers were looking for a sequel to

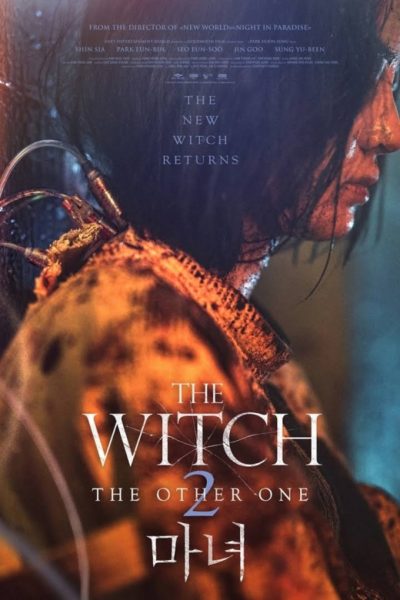

This dystopian future takes place after the United States of America is no longer united, having fragmented into a group of disparate regions that exist in an uneasy piece with each other. The heroine is 14-year-old Caroline, who lives in a remote part of the Appalachians, her town loosely affiliated to the People’s Republic of Virginia. She’s a scout, and one day encounters forces from the Democratic Alliance. The population of her village who escape, head towards the state capital of Warrenville, pursued by the invading army. On the way, Caroline begins to come into startling abilities which were literally injected into her as a small child.

This dystopian future takes place after the United States of America is no longer united, having fragmented into a group of disparate regions that exist in an uneasy piece with each other. The heroine is 14-year-old Caroline, who lives in a remote part of the Appalachians, her town loosely affiliated to the People’s Republic of Virginia. She’s a scout, and one day encounters forces from the Democratic Alliance. The population of her village who escape, head towards the state capital of Warrenville, pursued by the invading army. On the way, Caroline begins to come into startling abilities which were literally injected into her as a small child. The above – though expressed rather more bluntly! – was Chris’s reaction to the opening scene, in which Nanisca (Davis) leads her female troops, the Agojie, in the ambush of slavers from the neighbouring Oyo tribe. The Oyo are rivals to the Kingdom of Dahomey, under King Ghezo (John Boyega), who relies on Nanisca and the Agojie to protect his territory, and it’s getting closer to all-out war. The Agojie get a new recruit, Nawi (Mbedu), whose father drops her off at the palace gate, because of her refusal to accept an arranged marriage. Nawi turns out to have a very close connection to Nanisca, but also ends up captured by the Oyo and needs to escape before being sold to Brazilian slavers.

The above – though expressed rather more bluntly! – was Chris’s reaction to the opening scene, in which Nanisca (Davis) leads her female troops, the Agojie, in the ambush of slavers from the neighbouring Oyo tribe. The Oyo are rivals to the Kingdom of Dahomey, under King Ghezo (John Boyega), who relies on Nanisca and the Agojie to protect his territory, and it’s getting closer to all-out war. The Agojie get a new recruit, Nawi (Mbedu), whose father drops her off at the palace gate, because of her refusal to accept an arranged marriage. Nawi turns out to have a very close connection to Nanisca, but also ends up captured by the Oyo and needs to escape before being sold to Brazilian slavers. There are a couple of points to note going in. This was one of “12 Westerns in 12 months”, a project run by the director during 2020. It also proudly pronounces itself as the first ever Western feature to be shot entirely on an iPhone. Both of these do lead to limitations. The sheer speed involved obvious has an impact, and I can’t help wondering if a more measured approach would have been better for the end product. As for the iPhone… Well, on the plus side it looked perfectly watchable on my 49″ television, especially the outdoor scenes. However, the indoor sequences seemed almost

There are a couple of points to note going in. This was one of “12 Westerns in 12 months”, a project run by the director during 2020. It also proudly pronounces itself as the first ever Western feature to be shot entirely on an iPhone. Both of these do lead to limitations. The sheer speed involved obvious has an impact, and I can’t help wondering if a more measured approach would have been better for the end product. As for the iPhone… Well, on the plus side it looked perfectly watchable on my 49″ television, especially the outdoor scenes. However, the indoor sequences seemed almost  This is set in the everyday world – but with one major tweak. Witchcraft exists, and has been outlawed in the United States by the 11th amendment. Now, government agents from the BWI seek out witches, using tried and true methods from the middle ages (the “sink test” is exactly what it sounds like), and punish those found or suspected to be practicing witchcraft. But those opposed to this have set up an “underground railroad” to smuggle the targets over the boarder to Mexico. Teenage girl Claire (Adlon) is part of one such family, courtesy of her mom Martha (Elizabeth Mitchell); Dad is out of the picture. Claire is rather ambivalent about their activism, since she just wants to fit in at school. But the arrival of Fiona (Cowen) and her little sister, siblings whose mother was burned at the stake, forces Claire out of her professed neutrality,. Especially as the investigation of the unrelenting BWI Agent Hawthorne (Camargo) gets closer to home.

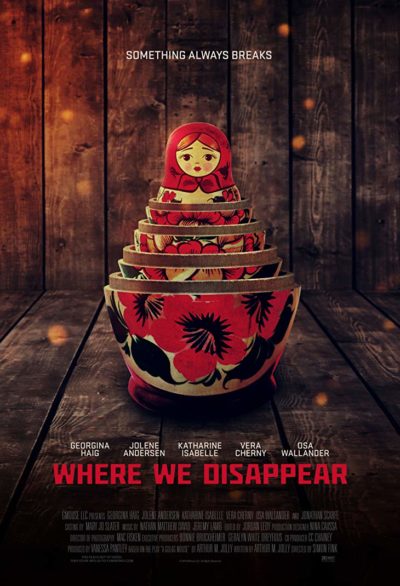

This is set in the everyday world – but with one major tweak. Witchcraft exists, and has been outlawed in the United States by the 11th amendment. Now, government agents from the BWI seek out witches, using tried and true methods from the middle ages (the “sink test” is exactly what it sounds like), and punish those found or suspected to be practicing witchcraft. But those opposed to this have set up an “underground railroad” to smuggle the targets over the boarder to Mexico. Teenage girl Claire (Adlon) is part of one such family, courtesy of her mom Martha (Elizabeth Mitchell); Dad is out of the picture. Claire is rather ambivalent about their activism, since she just wants to fit in at school. But the arrival of Fiona (Cowen) and her little sister, siblings whose mother was burned at the stake, forces Claire out of her professed neutrality,. Especially as the investigation of the unrelenting BWI Agent Hawthorne (Camargo) gets closer to home. That’s what happened here, about a month ago,with Quinn wanting to move in the direction of engagement and marriage and Nadia not willing to, leading to a messy breakup that left him very hurt and her “feeling like [vulgarism deleted].” :-( On top of that stress, when this book opens, she’s in rural Michigan on a job (of the kind that she doesn’t advertise). That quickly results, though through no fault of her own, in a traumatic event which has her on the point of meltdown. But before long, she’s in for a moral and emotional ordeal which will make her present distresses look relatively mild.

That’s what happened here, about a month ago,with Quinn wanting to move in the direction of engagement and marriage and Nadia not willing to, leading to a messy breakup that left him very hurt and her “feeling like [vulgarism deleted].” :-( On top of that stress, when this book opens, she’s in rural Michigan on a job (of the kind that she doesn’t advertise). That quickly results, though through no fault of her own, in a traumatic event which has her on the point of meltdown. But before long, she’s in for a moral and emotional ordeal which will make her present distresses look relatively mild.