★★★

“Tree’s company…”

This has the potential to be truly bad, and you need to be willing to look past ropey production values, a possibly deliberately shaky grasp of period (unless “Daisy” really was a popular girls’ name in early medieval times…) and uncertainty as to whether or not this is intended to be a comedy. Yet, I have to admire its “everything including the kitchen sink” approach: throwing together elements from genres as disparate as Vikings, zombies, aliens, sword ‘n’ sorcery and female vengeance shows… well, ambition, at the very least.

This has the potential to be truly bad, and you need to be willing to look past ropey production values, a possibly deliberately shaky grasp of period (unless “Daisy” really was a popular girls’ name in early medieval times…) and uncertainty as to whether or not this is intended to be a comedy. Yet, I have to admire its “everything including the kitchen sink” approach: throwing together elements from genres as disparate as Vikings, zombies, aliens, sword ‘n’ sorcery and female vengeance shows… well, ambition, at the very least.

The story starts with a group of women, led by Atheled (McTernan), infiltrating a priory. They seek revenge on the monks, because of a sideline in human trafficking which has cost the women dearly. Their plan for vengeance is somewhat derailed by a local lord turning up, and entirely derailed by the arrival of a horde of Vikings, in turn hotly pursued by what can only be described as demonic shrubbery – not for nothing are they referred to and credited as “tree bastards.” To survive through the night is going to take an unholy alliance between the various parties, as well as some captives in the basement – fortunately, those include someone who can speak Viking (McNab). Given their radically different goals, this will present problems of its own.

Wisely, for budgetary reasons, action is largely constrained to the main hall of the priory, with occasional forays outside. This set-up is very Night of the Living Dead, and the tree bastards are also infectious, albeit not quite in the traditional zombie sense. However, it’s in the creatures that the film’s limited resources are most painfully obvious, with them being little more than obviously blokes in masks. Although the boss shrub does occasionally look impressive, when shot from the right angle, it feels a bit much, and is a case where less might well have been more. Just make them nameless berserkers, you’d have much the same impact and save yourself a lot of time, money and effort.

The chief saving grace are the performances. McTernan has the inner steel to go with her crossbow bolts; her colleagues, Seren (Hoult) and Rosalind (Schnitzler) in particular, are very easy to root for; and the nameless translator has perhaps the most interesting character. It’s these that kept me watching, such as in the atmospheric scene when the backstory of the tree bastards is explained. Though told rather than shown, it’s delivered with enough energy to prove more effective than some other elements (martial arts? gunpowder?), which had me sighing in irritation.

To be perfectly clear, it’s a case where you need to go in with your expectations suitably managed, i.e. keep ’em on the low-down. Based on the blandly generic DVD sleeve and title, I probably wouldn’t have even bothered, and certainly would not have expected any action heroines. As such, this was a pleasant surprise, and it kept me more entertained than I feared it might. My advice is, treat it as a loving tribute to a whole slew of B-movie genres, no more and no less.

Dir: Jack Burton

Star: Michelle McTernan, Rosanna Hoult, Samantha Schnitzler, Adam McNab

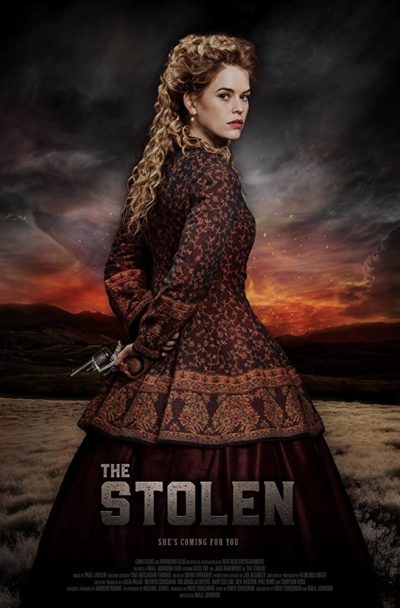

Rarely has such promise been so spectacularly and vigorously squandered. For this starts well enough. In 19th century New Zealand, English ex-pat Charlotte (Eve) is settling into a new life with her husband and newborn child. This is upturned when a midnight raid leaves her husband dead and the baby kidnapped. Months later, after everyone else has moved on, she gets a ransom demand in the mail, and she tracks its source to Goldtown. This remote outpost is truly an Antipodean version of the Wild West, a rough-edged mining town run by Joshua McCullen (Davenport). Braving all manner of threats – not least, that the only other women there are prostitutes – Charlotte makes the perilous journey to the frontier settlement in search of her son.

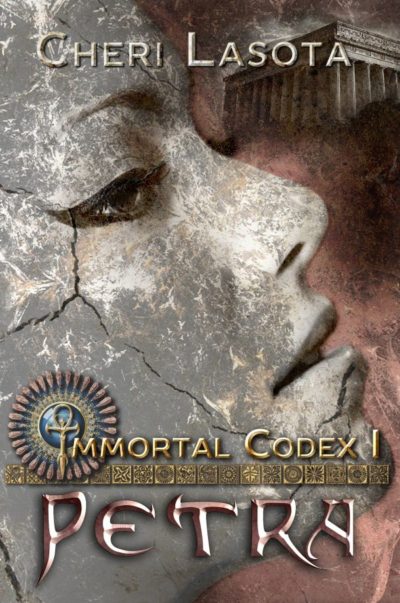

Rarely has such promise been so spectacularly and vigorously squandered. For this starts well enough. In 19th century New Zealand, English ex-pat Charlotte (Eve) is settling into a new life with her husband and newborn child. This is upturned when a midnight raid leaves her husband dead and the baby kidnapped. Months later, after everyone else has moved on, she gets a ransom demand in the mail, and she tracks its source to Goldtown. This remote outpost is truly an Antipodean version of the Wild West, a rough-edged mining town run by Joshua McCullen (Davenport). Braving all manner of threats – not least, that the only other women there are prostitutes – Charlotte makes the perilous journey to the frontier settlement in search of her son. Petra is a teenage Roman slave at around the birth of Christ. She is completely under the thumb of her sadistic master, Clarius, until a strange conjunction of events and a poisonous herb with mystical qualities changes the power dynamic entirely. Both of them, together with her lover, Lucius, attain immortality. But it’s an immortality which requires the two men to drink from Petra annually, or they will degenerate into sub-human monsters. Neither is happy with the arrangement: Clarius is not used to being reliant on anyone, least of all his former property, and Lucius hates the fact Petra agreed to submit to their ex-master, in order to save him. As the centuries stretch into millennia, Petra begins, slowly, to put together a group people who will be capable of defeating Lucius and the immortals he has recruited, allowing her to live in eternal peace with Lucius.

Petra is a teenage Roman slave at around the birth of Christ. She is completely under the thumb of her sadistic master, Clarius, until a strange conjunction of events and a poisonous herb with mystical qualities changes the power dynamic entirely. Both of them, together with her lover, Lucius, attain immortality. But it’s an immortality which requires the two men to drink from Petra annually, or they will degenerate into sub-human monsters. Neither is happy with the arrangement: Clarius is not used to being reliant on anyone, least of all his former property, and Lucius hates the fact Petra agreed to submit to their ex-master, in order to save him. As the centuries stretch into millennia, Petra begins, slowly, to put together a group people who will be capable of defeating Lucius and the immortals he has recruited, allowing her to live in eternal peace with Lucius. I’m not kidding. Director Deodato is best known as the man behind one of the most notorious of all “video nasties,” a film which created such a furore, he had to produce the actors to convince the Italian courts he hadn’t killed them. But in almost fifty years of work (he’s still active today), Deodato has done everything from spaghetti Westerns to science-fiction. And more than a decade before Holocaust, back in 1968, he directed this bawdy action-comedy.

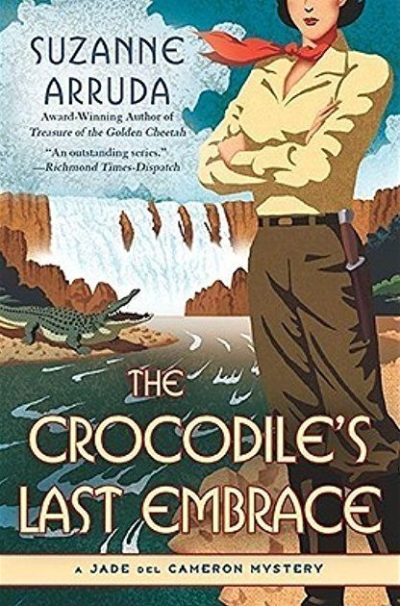

I’m not kidding. Director Deodato is best known as the man behind one of the most notorious of all “video nasties,” a film which created such a furore, he had to produce the actors to convince the Italian courts he hadn’t killed them. But in almost fifty years of work (he’s still active today), Deodato has done everything from spaghetti Westerns to science-fiction. And more than a decade before Holocaust, back in 1968, he directed this bawdy action-comedy. This sixth installment in Arruda’s outstanding series has much in common, in terms of style and other characteristics, with the preceding five. We pick up here in February 1921, and our setting is the familiar one of Nairobi and its environs; all or most of the supporting cast we’ve come to like are here, as well as Jade herself.

This sixth installment in Arruda’s outstanding series has much in common, in terms of style and other characteristics, with the preceding five. We pick up here in February 1921, and our setting is the familiar one of Nairobi and its environs; all or most of the supporting cast we’ve come to like are here, as well as Jade herself. Generally, if someone is roaming the country, carrying out brutal attacks on apparently innocent citizens, blinding and disfiguring them, they’d be the villain of the piece, right? Not so here. For despite such distinctly non-heroic actions, Iron Swallow (Lee) is the heroine, disabling the men she holds responsible for killing her father years earlier. Needless to say, they’re not exactly impressed with the situation. To make matters worse, someone is flat-out killing her targets, intent on covering up something or other, and is trying to make it look like Swallow is responsible, by leaving her trademark darts behind at the scene. There are also two friends (Tao and Chung) rattling around, the son and pupil respectively of the region’s leading martial arts master Chu Hsiao Tien (Yuen), who get involved in the murky situation because Chu is one of Swallow’s targets and has hired a particularly loathsome assassin to bury the case.

Generally, if someone is roaming the country, carrying out brutal attacks on apparently innocent citizens, blinding and disfiguring them, they’d be the villain of the piece, right? Not so here. For despite such distinctly non-heroic actions, Iron Swallow (Lee) is the heroine, disabling the men she holds responsible for killing her father years earlier. Needless to say, they’re not exactly impressed with the situation. To make matters worse, someone is flat-out killing her targets, intent on covering up something or other, and is trying to make it look like Swallow is responsible, by leaving her trademark darts behind at the scene. There are also two friends (Tao and Chung) rattling around, the son and pupil respectively of the region’s leading martial arts master Chu Hsiao Tien (Yuen), who get involved in the murky situation because Chu is one of Swallow’s targets and has hired a particularly loathsome assassin to bury the case. This works rather better as historical fiction than an action novel, and is set in the late 15th century, when the province of Brittany was fighting to remain independent from France. Such high-level political machinations are far above the heads of most inhabitants, who are busy with everyday survival. At the beginning of the book, this includes the heroine, 17-year-old Ismae, who is more concerned about her upcoming, unwanted marriage – more of a sale by her father, to be honest – to a brutal husband. Rescue comes in an unexpected form, as she is whisked away to the Convent of St. Mortain, devoted to one of the pagan gods, absorbed into the Catholic faith as a saint. Mortain’s field is death, and Ismae, who has a natural immunity to poison, is trained in his dark arts. She becomes a tool used by the Mother Superior – albeit for political ends as much as religious ones.

This works rather better as historical fiction than an action novel, and is set in the late 15th century, when the province of Brittany was fighting to remain independent from France. Such high-level political machinations are far above the heads of most inhabitants, who are busy with everyday survival. At the beginning of the book, this includes the heroine, 17-year-old Ismae, who is more concerned about her upcoming, unwanted marriage – more of a sale by her father, to be honest – to a brutal husband. Rescue comes in an unexpected form, as she is whisked away to the Convent of St. Mortain, devoted to one of the pagan gods, absorbed into the Catholic faith as a saint. Mortain’s field is death, and Ismae, who has a natural immunity to poison, is trained in his dark arts. She becomes a tool used by the Mother Superior – albeit for political ends as much as religious ones.

Although it’s self-contained enough to be read as a stand-alone, this is actually the sixth novel in Coldsmith’s popular Spanish Bit Saga, a multi-generational epic of the history of the Plains Indians after their culture is transformed by the coming of the horse, focusing on a tribe that calls itself (as most of them did) simply “the People.” (It’s a fictional, composite tribe, but probably modeled most closely on the Cheyenne.) In terms of style and literary vision, it has a lot in common with the series opener, Trail of the Spanish Bit, and the numerous other series installments I’ve read. However, it proved to be my favorite (and, I believe, my wife’s as well). Re-reading it, and re-experiencing parts I’d forgotten, was a reminder of how much I liked it the first time, and still do!

Although it’s self-contained enough to be read as a stand-alone, this is actually the sixth novel in Coldsmith’s popular Spanish Bit Saga, a multi-generational epic of the history of the Plains Indians after their culture is transformed by the coming of the horse, focusing on a tribe that calls itself (as most of them did) simply “the People.” (It’s a fictional, composite tribe, but probably modeled most closely on the Cheyenne.) In terms of style and literary vision, it has a lot in common with the series opener, Trail of the Spanish Bit, and the numerous other series installments I’ve read. However, it proved to be my favorite (and, I believe, my wife’s as well). Re-reading it, and re-experiencing parts I’d forgotten, was a reminder of how much I liked it the first time, and still do!