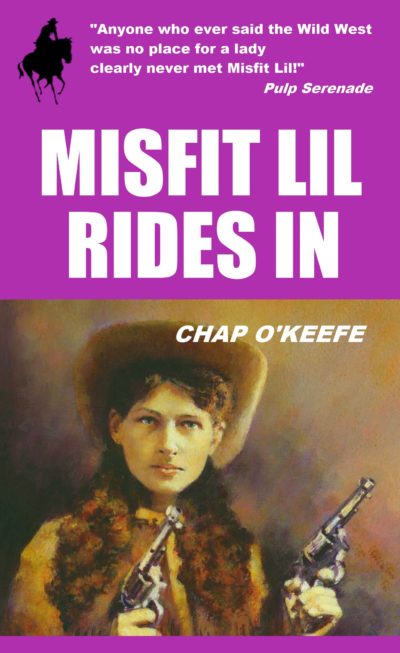

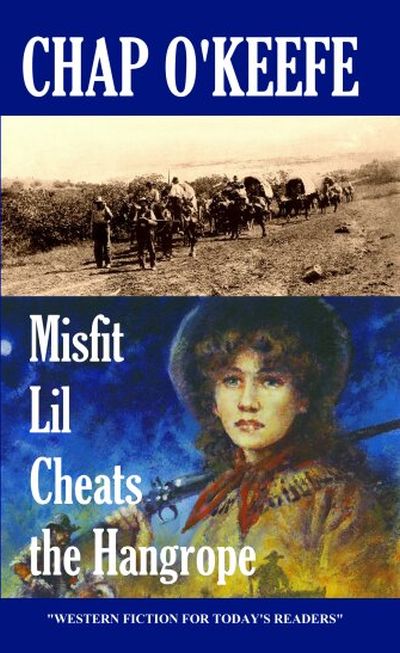

Misfit Lil Rides In: Literary rating: ★★★, Kick-butt quotient: ☆☆

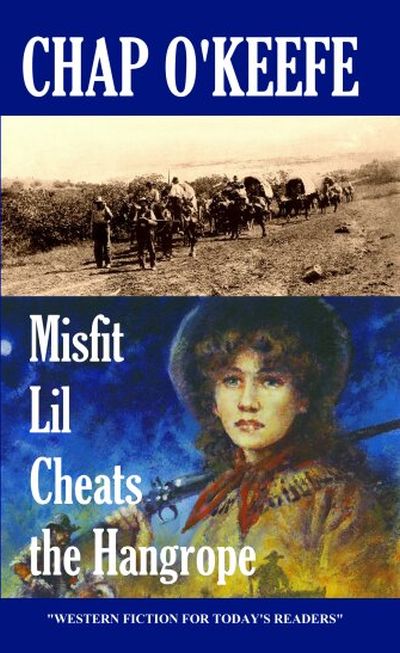

Misfit Lil Cheats the Hangrope: Literary rating: ★★★★, Kick-butt quotient: ☆☆½

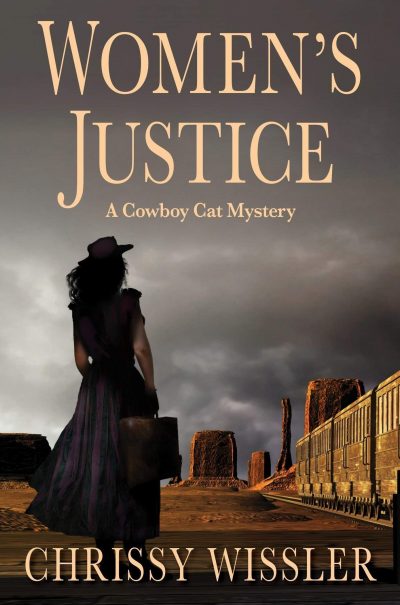

The Western is typically among the most macho of genres, and this applies to the world of pulp fiction as much as to movies. There are exceptions: Werner has covered quite a few in the past, such as The Complete Adventures of Senorita Scorpion, and I recently dipped my toe in the genre, with the first book of Chrissy Wissler’s Cowboy Cat series, Women’s Justice. While set in the past, that did have a contemporary feel to it: Cat felt like a 21st-century heroine in an antiquated world. That seems significantly less the case for Miss Lilian Goodnight, despite her nickname of “Misfit Lil”. These two stories feel like a throwback to the golden age of pulp. There is no obvious agenda beyond entertaining the reader, which is almost refreshing. They’re quick, uncomplex, and occasionally slightly disreputable reads. Nothing wrong with these elements, I should stress.

The Western is typically among the most macho of genres, and this applies to the world of pulp fiction as much as to movies. There are exceptions: Werner has covered quite a few in the past, such as The Complete Adventures of Senorita Scorpion, and I recently dipped my toe in the genre, with the first book of Chrissy Wissler’s Cowboy Cat series, Women’s Justice. While set in the past, that did have a contemporary feel to it: Cat felt like a 21st-century heroine in an antiquated world. That seems significantly less the case for Miss Lilian Goodnight, despite her nickname of “Misfit Lil”. These two stories feel like a throwback to the golden age of pulp. There is no obvious agenda beyond entertaining the reader, which is almost refreshing. They’re quick, uncomplex, and occasionally slightly disreputable reads. Nothing wrong with these elements, I should stress.

Lil is the daughter of cattle rancher Ben Goodnight, who has resisted all attempts by her father, a widower, to turn her into a proper young lady. In particular, he sent her to a Boston boarding school; rather than uplifting Lillian, she succeeded in corrupting the other pupils, and we sent home in disgrace, earning her nickname. Since then, she has been riding free, helping out on the ranch, with occasional stunts that bring her into conflict with the local authority, such as showing off her pistol marksmanship on the local Main Street. “Once she hammered five four-inch nails halfways into a boardwalk post, then drove each of ’em in with a bullet from twenty paces.” The local sheriff was unimpressed, locking her up overnight, until her long-suffering father bailed her out. But Lil gained another nickname: “Princess o’ Pistoleers”.

Beyond the heroine, the players do overlap, in particular, a co-lead in both books is Jackson Farraday, local scout and guide, who takes on commissions both for the army and for civilians seeking to cross the dangerous territory. She has a crush on him, though acknowledges its futility, with him being twice her age (doing the math based off this and other information, it makes Lil about twenty, and Jackson almost forty), and he similarly has no interest in her for romantic purposes. But he certainly respects her skills and bravery, and they have no hesitation in helping each other out when needed. Which is the case in both of these novels, with Farraday being falsely accused of murder in each.

The first, Misfit Lil Rides In, sees him framed for killing the wife of store owner Axel Boorman. While Axel was actually the killer, in a fit of jealous rage, with the help of the local law, Farraday is blamed, and a posse sent after him. With Lil’s aid, the posse is fended off, though she is arrested, and Jackson believed to have fallen to his doom. He is actually still alive, but ends up captured by the local Apaches, so both are in serious trouble. Even after Jackson escapes, he falls foul of an Army officer with a grudge against him, and ends up behind bars too. Lil needs to free herself, break her friend out, then find some way of proving the truth – not least about Boorman’s scheme to sell guns to the Indians – and convince the authorities to take action.

I think my major surprise was how relatively even it felt like the book was split between Jackson and Lil. While Jackson isn’t a bad character, he is fairly generic as Western heroes go. I was considerably more interested in Lil, and every page that detailed her colleague’s adventures felt like it was wasted, especially as the whole book is under two hundred pages. I almost found myself speed-reading the Faraday heavy sections, to get back to what Lil was doing. Outside of the gun-battle against the posse, that was largely using her brain rather than her pistols. But of particular note here is an author’s afterword, Heroines of the Wilder West, in which O’Keefe discusses some of Lil’s predecessors and inspirations, such as Hurricane Nell and Denver Doll. I sense a rabbit-hole for future exploration, and may have to watch Along Came Jones as well, for its proto-heroine.

I think my major surprise was how relatively even it felt like the book was split between Jackson and Lil. While Jackson isn’t a bad character, he is fairly generic as Western heroes go. I was considerably more interested in Lil, and every page that detailed her colleague’s adventures felt like it was wasted, especially as the whole book is under two hundred pages. I almost found myself speed-reading the Faraday heavy sections, to get back to what Lil was doing. Outside of the gun-battle against the posse, that was largely using her brain rather than her pistols. But of particular note here is an author’s afterword, Heroines of the Wilder West, in which O’Keefe discusses some of Lil’s predecessors and inspirations, such as Hurricane Nell and Denver Doll. I sense a rabbit-hole for future exploration, and may have to watch Along Came Jones as well, for its proto-heroine.

However, any issues are well addressed in Misfit Lil Cheats the Hangrope; it seems O’Keefe has grown more comfortable with his characters by this, the most recent entry. While Faraday plays a significant role here, Lil feels more the focus, and the story flows around her in a fluid way. It begins when Lil helps rescue a wagon train of settlers headed west, who make an ill-informed decision to try and cross the mountains as the weather comes down. She gets Jackson a job as co-guide on the train, but the previous sole guide, Luke Reiner, is far from happy about it. When the corpse of a young, female settler turns up drowned in a creek, suspicion falls on Farraday, because Lil isn’t the only woman to find him attractive. It’s up to her to find the necessary proof that will exonerate her friend, before Reiner succeeds in whipping up a lynch mob.

There’s a good sense of escalation here, and it’s a solid page-turner, with each incident providing a natural progression into the next. It works both as a Western and as a whodunnit mystery, with the killer’s identity shrouded in uncertainty. As for the cause of death… Well, that might be one of those “slightly disreputable” elements mentioned earlier, even if there are worse ways to go, it has to be said! Again though, Lil seems to be almost loathe to use her shooting skills. To me, the point of guns is that they are a great equalizer, allowing the weak (or “weaker sex,” to use a slightly pejorative term!) to stand up against the strong. But over both volumes, I’m not sure there was any real demonstration of the sure-shot abilities described early in the first book.

This is a relatively minor complaint, however. These may be stories, rather than Great Literature; yet there’s an absolute lack of apparent pretension to the approach, which I appreciated. If the intention of the author was, as discussed above, simply to provide a good yarn that entertains the reader, I’d say they accomplish that mission.

Author: Chap O’Keefe

Publisher: Amazon Digital Services, available through Amazon, both as a paperback and an e-book

Books 1 and 7 in the Misfit Lil series.

I was provided copies of both volumes, in exchange for an honest review.

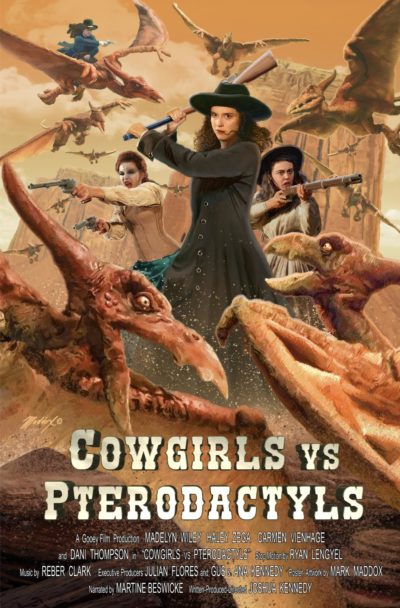

A title like this is inevitably going to come with all manner of expectations, and these will largely be things that any film is ill-equipped to fulfill. That’s all the more the case, when your movie is clearly a super low-budget endeavour. By most objective standards, this could be seen as terrible, and I wouldn’t argue with you. But for all the flaws, and enthusiasm that exceeds technical ability, this is made with clear affection for its elements. That goes quite some way in mind to excusing the problems. In particular, there’s a love for the world of stop-motion dinosaurs, which I share. For example, the narrator is Martine Beswick, who co-starred in the classic stop-motion dino epic, One Million Years B.C. I presume Raquel Welch was unavailable…

A title like this is inevitably going to come with all manner of expectations, and these will largely be things that any film is ill-equipped to fulfill. That’s all the more the case, when your movie is clearly a super low-budget endeavour. By most objective standards, this could be seen as terrible, and I wouldn’t argue with you. But for all the flaws, and enthusiasm that exceeds technical ability, this is made with clear affection for its elements. That goes quite some way in mind to excusing the problems. In particular, there’s a love for the world of stop-motion dinosaurs, which I share. For example, the narrator is Martine Beswick, who co-starred in the classic stop-motion dino epic, One Million Years B.C. I presume Raquel Welch was unavailable…

It’s about the year 1880, and Jessica Hartwell (Currie) is heading out West in a wagon with her preacher husband. They encounter the gang of Frank Brock (Frank); they repeatedly rape Jessica, before shooting her husband fatally, and leaving her for dead. She survives, returning to health with the help of prospector Rufe, who sports an unfortunate, obviously fake beard, yet also teaches the young woman how to shoot. For Jessi has vengeance on her mind, and to assist her in this path, she liberates three other women from the custody of Sheriff Clay (Lund). There’s outlaw Rachel (Jennifer Bishop); saloon girl Claire (Regina Carrol); and Indian Kana (the not-exactly Indian Stern), who had been a part of Frank’s gang until he abandoned her.

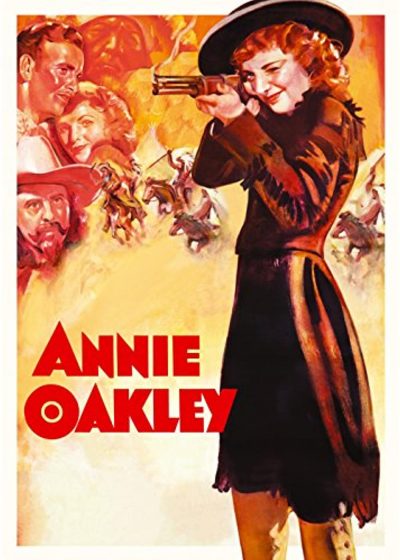

It’s about the year 1880, and Jessica Hartwell (Currie) is heading out West in a wagon with her preacher husband. They encounter the gang of Frank Brock (Frank); they repeatedly rape Jessica, before shooting her husband fatally, and leaving her for dead. She survives, returning to health with the help of prospector Rufe, who sports an unfortunate, obviously fake beard, yet also teaches the young woman how to shoot. For Jessi has vengeance on her mind, and to assist her in this path, she liberates three other women from the custody of Sheriff Clay (Lund). There’s outlaw Rachel (Jennifer Bishop); saloon girl Claire (Regina Carrol); and Indian Kana (the not-exactly Indian Stern), who had been a part of Frank’s gang until he abandoned her. While not exactly an accurate retelling of the life of noted sure-shot Annie Oakley, this is breezily entertaining. Indeed, you can make a case for this being one of the earliest “girls with guns” films to come out in the talking pictures era. There’s no denying Oakley (Stanwyck) qualifies here. The first time we see her, she’d delivering a load of game birds – all shot through the head to avoid damaging the flesh – to her wholesaler. When barnstorming sharpshooter Toby Walker (Foster) blows into town, Annie ends up in a match with him, which she ends up throwing, due in part to her crush on him. She still gets a job alongside Walker, in the Wild West show run by the renowned ‘Buffalo Bill’ Cody (Olsen) and his partner, Jeff Hogarth (Douglas). But Annie and Toby’s relationship fractures after he accidentally shoots her in the hand, while concealing an injury affecting his sight.

While not exactly an accurate retelling of the life of noted sure-shot Annie Oakley, this is breezily entertaining. Indeed, you can make a case for this being one of the earliest “girls with guns” films to come out in the talking pictures era. There’s no denying Oakley (Stanwyck) qualifies here. The first time we see her, she’d delivering a load of game birds – all shot through the head to avoid damaging the flesh – to her wholesaler. When barnstorming sharpshooter Toby Walker (Foster) blows into town, Annie ends up in a match with him, which she ends up throwing, due in part to her crush on him. She still gets a job alongside Walker, in the Wild West show run by the renowned ‘Buffalo Bill’ Cody (Olsen) and his partner, Jeff Hogarth (Douglas). But Annie and Toby’s relationship fractures after he accidentally shoots her in the hand, while concealing an injury affecting his sight.

In the 1880’s, the town of Butte, Montana is a mining boom-town – instead of gold, it’s mostly copper which fuels its economy. The wealth comes at a cost, as the huge amounts of acrid smoke belched from the smelters and plants turns day into night, along with creating perpetually “noxious, disgusting air.” Off the train and into this smog steps Cat, a woman with no shortage of a past. A former prostitute, but also a ranch-hand, her preferred outfit of blue jeans and six-shooter is most atypical for a woman of the times. Almost immediately, she is drawn into the mysterious and suspicious death on the street of another “fallen woman,” Norma. The apparent cover-up goes right up to “Copper Kings” such as Marcus Daly (a real tycoon from that time and place), and it quickly becomes clear that whoever was behind Norma’s demise, is none to happy to find Cat looking into the matter. To find the truth, she’s going to have to navigate her way through both ends of Butte society.

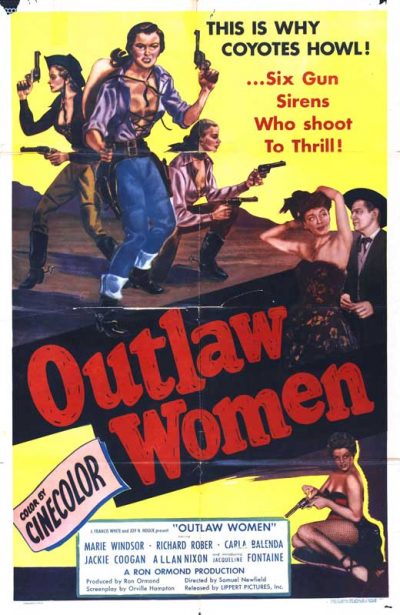

In the 1880’s, the town of Butte, Montana is a mining boom-town – instead of gold, it’s mostly copper which fuels its economy. The wealth comes at a cost, as the huge amounts of acrid smoke belched from the smelters and plants turns day into night, along with creating perpetually “noxious, disgusting air.” Off the train and into this smog steps Cat, a woman with no shortage of a past. A former prostitute, but also a ranch-hand, her preferred outfit of blue jeans and six-shooter is most atypical for a woman of the times. Almost immediately, she is drawn into the mysterious and suspicious death on the street of another “fallen woman,” Norma. The apparent cover-up goes right up to “Copper Kings” such as Marcus Daly (a real tycoon from that time and place), and it quickly becomes clear that whoever was behind Norma’s demise, is none to happy to find Cat looking into the matter. To find the truth, she’s going to have to navigate her way through both ends of Butte society. The city of Silver Creek is on the way out, and many of its inhabitants are leaving, including town doctor Bob Ridgeway (Nixon). Originally heading to Kansas City, he is convinced at gunpoint to take up a position instead in “Las Mujeres.” That’s Spanish for “The women,” and is an appropriate name since the place is a gynocratic society, where the ladies are in charge. Top of the heap is Iron Mae McLeod (Windsor), who runs the local saloon and ensures that the the other women in the town are kept safe from exploitation. She does, however, have to navigate the straits between aspirational gambler Woody Callaway (Rober) and outlaw Frank Slater. Ridgeway, meanwhile, because the target of affection for both Beth Larrabee (Balenda), one of Mae’s enforcers, and her big sister and star of the saloon’s show, Ellen. But when all of Mae’s money is about to be transferred out of Silver Creek, and becomes a target for Slater and his gang, romance has to take a back seat.

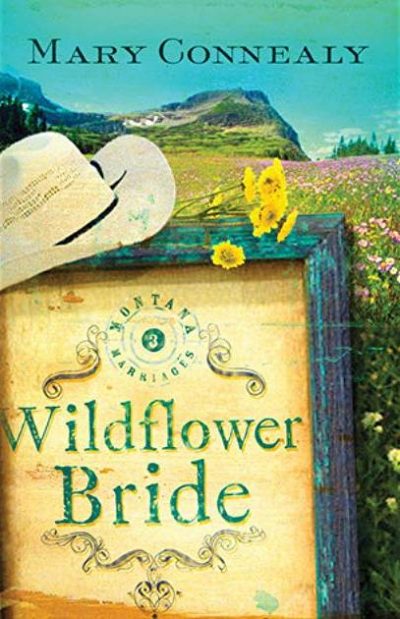

The city of Silver Creek is on the way out, and many of its inhabitants are leaving, including town doctor Bob Ridgeway (Nixon). Originally heading to Kansas City, he is convinced at gunpoint to take up a position instead in “Las Mujeres.” That’s Spanish for “The women,” and is an appropriate name since the place is a gynocratic society, where the ladies are in charge. Top of the heap is Iron Mae McLeod (Windsor), who runs the local saloon and ensures that the the other women in the town are kept safe from exploitation. She does, however, have to navigate the straits between aspirational gambler Woody Callaway (Rober) and outlaw Frank Slater. Ridgeway, meanwhile, because the target of affection for both Beth Larrabee (Balenda), one of Mae’s enforcers, and her big sister and star of the saloon’s show, Ellen. But when all of Mae’s money is about to be transferred out of Silver Creek, and becomes a target for Slater and his gang, romance has to take a back seat. Barb and I discovered evangelical Christian author Mary Connealy through her Sophie’s Daughters trilogy, partially set in Montana in the years from 1878 to 1884. Several characters who figure in her earlier Montana Marriages trilogy, of which this novel is the third, also play important roles in the later one. So we were interested in their back stories; and when I found this book in a thrift store, it was a natural purchase! (We’ve also just started reading the second installment; long story!) This means we’re reading the trilogy in reverse order; so we started with much more knowledge of the characters’ future than the original readers would have (the read was more like a visit with old friends). However, I’ll avoid spoilers in this review. (Obviously, though, it might contain “spoilers” for the earlier Montana Marriages novels.)

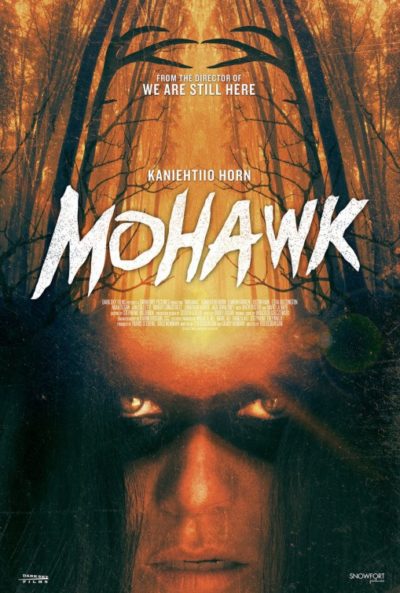

Barb and I discovered evangelical Christian author Mary Connealy through her Sophie’s Daughters trilogy, partially set in Montana in the years from 1878 to 1884. Several characters who figure in her earlier Montana Marriages trilogy, of which this novel is the third, also play important roles in the later one. So we were interested in their back stories; and when I found this book in a thrift store, it was a natural purchase! (We’ve also just started reading the second installment; long story!) This means we’re reading the trilogy in reverse order; so we started with much more knowledge of the characters’ future than the original readers would have (the read was more like a visit with old friends). However, I’ll avoid spoilers in this review. (Obviously, though, it might contain “spoilers” for the earlier Montana Marriages novels.) This takes place in upstate New York during the 1812 war between Britain and America, when combatants are courting the Mohawk tribe to join forces with them. The natives are suspicious of both, and won’t commit to either. Working for the British is Joshua (Farren), who is in a slightly odd, three-way relationship with Mohawk warrioress Oak (Horn) and fellow native Calvin (Rain). On the other side is Hezekiah Holt (Buzzington), and his small band of Americans, who are out for redcoat blood. When they blame the Mohawk for murdering some of their number, their violence quickly extends to encompass Oak and Calvin, as well as Joshua. After Oak is left all alone, she goes on the war-path to take revenge on Holt and his men.

This takes place in upstate New York during the 1812 war between Britain and America, when combatants are courting the Mohawk tribe to join forces with them. The natives are suspicious of both, and won’t commit to either. Working for the British is Joshua (Farren), who is in a slightly odd, three-way relationship with Mohawk warrioress Oak (Horn) and fellow native Calvin (Rain). On the other side is Hezekiah Holt (Buzzington), and his small band of Americans, who are out for redcoat blood. When they blame the Mohawk for murdering some of their number, their violence quickly extends to encompass Oak and Calvin, as well as Joshua. After Oak is left all alone, she goes on the war-path to take revenge on Holt and his men. Rarely has such promise been so spectacularly and vigorously squandered. For this starts well enough. In 19th century New Zealand, English ex-pat Charlotte (Eve) is settling into a new life with her husband and newborn child. This is upturned when a midnight raid leaves her husband dead and the baby kidnapped. Months later, after everyone else has moved on, she gets a ransom demand in the mail, and she tracks its source to Goldtown. This remote outpost is truly an Antipodean version of the Wild West, a rough-edged mining town run by Joshua McCullen (Davenport). Braving all manner of threats – not least, that the only other women there are prostitutes – Charlotte makes the perilous journey to the frontier settlement in search of her son.

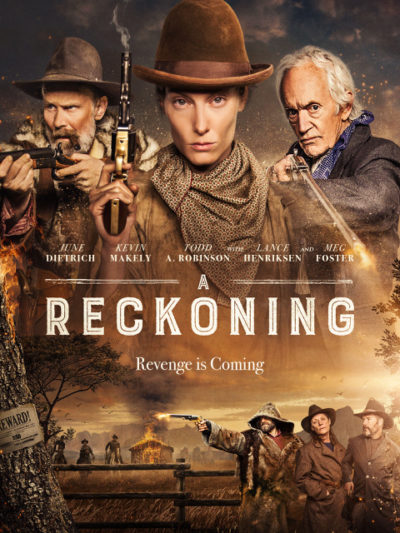

Rarely has such promise been so spectacularly and vigorously squandered. For this starts well enough. In 19th century New Zealand, English ex-pat Charlotte (Eve) is settling into a new life with her husband and newborn child. This is upturned when a midnight raid leaves her husband dead and the baby kidnapped. Months later, after everyone else has moved on, she gets a ransom demand in the mail, and she tracks its source to Goldtown. This remote outpost is truly an Antipodean version of the Wild West, a rough-edged mining town run by Joshua McCullen (Davenport). Braving all manner of threats – not least, that the only other women there are prostitutes – Charlotte makes the perilous journey to the frontier settlement in search of her son. Considering how little actually happens here, I enjoyed this considerably more than expected. It kicks off with 19th-century settler Mary O’Malley (Dietrich) being informed her husband has been brutally slain. Despite the warnings of fellow settler Henry Breck (a small role for Lance Henriksen), Mary heads out on the trail through Oregon for revenge, looking for the serial killer responsible. He’s known as “Marrow” (Makely), for reasons which eventually become clear. She encounters Jebediah (Robinson), a bounty-hunter after Marrow who doesn’t appreciate the competition, and Barley (Crow), a trader who offers and receives temporary companionship.

Considering how little actually happens here, I enjoyed this considerably more than expected. It kicks off with 19th-century settler Mary O’Malley (Dietrich) being informed her husband has been brutally slain. Despite the warnings of fellow settler Henry Breck (a small role for Lance Henriksen), Mary heads out on the trail through Oregon for revenge, looking for the serial killer responsible. He’s known as “Marrow” (Makely), for reasons which eventually become clear. She encounters Jebediah (Robinson), a bounty-hunter after Marrow who doesn’t appreciate the competition, and Barley (Crow), a trader who offers and receives temporary companionship.