★★★½

“All in, all out!”

When I reviewed Russian fencing film On the Edge, I said, “I just need to find a synchronized swimming movie.” While this is a documentary, with all the positives and negatives of that genre, this fits the bill until Hollywood produces something more narrative. It follows the efforts of the Canadian team to get into the 2016 Rio Olympics. While normally, they’d be in as Pan-American champions, hosts Brazil got the spot reserved for the Americas. This forces Canada to go through the qualification tournament, battling their nemeses, Spain and Italy. The doc covers the arrival of new Chinese coach Meng Chen, efforts to get the most from her swimmers, and when this initially falls short, a radical re-invention of the team’s routine.

When I reviewed Russian fencing film On the Edge, I said, “I just need to find a synchronized swimming movie.” While this is a documentary, with all the positives and negatives of that genre, this fits the bill until Hollywood produces something more narrative. It follows the efforts of the Canadian team to get into the 2016 Rio Olympics. While normally, they’d be in as Pan-American champions, hosts Brazil got the spot reserved for the Americas. This forces Canada to go through the qualification tournament, battling their nemeses, Spain and Italy. The doc covers the arrival of new Chinese coach Meng Chen, efforts to get the most from her swimmers, and when this initially falls short, a radical re-invention of the team’s routine.

You may be wondering what one of the most mocked Olympic sports is doing on the site. But beneath the fixed grins, penguin walks and stripper make-up, lies one of the most intense, demanding and gruelling sports, for men or women. To quote one team member, it’s like “running an Olympic-level 400-metre sprint while holding your breath”. She’s not wrong. The most memorable sequence here is when a series of team members list the injuries suffered for their sport. Broken bones. Torn muscles. And concussions. So many concussions, an inevitable result of rapidly-moving limbs in close proximity to skulls. I wrote elsewhere about the sport, now called “artistic swimming”; read that if you want the full case for why it belongs here.

Alternatively, just watch the film, because you’ll likely leave giving the athletes the respect they deserve. It’s the result of throwaway lines like one saying she spends 7-12 hours a day in the pool. Or the relentless pressure of Chen, pushing to unlock their potential. Or team captain Morin succumbing to an eating disorder, this sport being as much about how you look as how you perform. However, I’d have liked to have seen more technical background, rather than another scene of Chen yelling at the team. Even simple things, like explaining they aren’t allowed to touch the bottom of the pool, would have enhanced the footage of them throwing team-mates into the air. Though there are still some staggeringly beautiful shots, using reflections, tilted cameras, etc. it is a shame they couldn’t use the performance music – presumably for rights reasons.

Interestingly, and perhaps pointedly, the team realizes its greatest results, after Chen adopts a more collaborative approach with them, and brings in external help. They even get an acting coach, to help improve their ability to convey emotions through movement. It’s nice too, to get a bit of insight into the aspiring Olympians, such as Holzner, for whom this has been an ambition since she was eight. We see the scrapbook she made when she was young (to help cope with a concussion!), and it helps foster an understanding of why people are willing to put themselves through this kind of ordeal. It all ends a bit messily: we don’t even see their final routine. But the journey is the thing here, not the destination, and you should be left with a new appreciation for the sport and its participants.

Dir: Jérémie Battaglia

Star: Claudia Holzner, Marie-Lou Morin, Meng Chen, Karine Thomas

This dates back from 2005, before Carano was a household name in the world of mixed martial arts, or a somewhat successful actress. At this point, she was only involved in the sport of muay thai, which as it’s name suggests, is a martial art originating in Thailand. She was one of five girls training in Las Vegas under Toddy – a nickname given because the teacher’s real name of Thohsaphol Sitiwatjana was too unpronounceable to Westerners! The goal of both Toddy and his students was a trip to Thailand to take on the best local practitioners of the sport. This “documentary” covers both their training and the visit itself, climaxing with Carano’s battle against the Thai champion.

This dates back from 2005, before Carano was a household name in the world of mixed martial arts, or a somewhat successful actress. At this point, she was only involved in the sport of muay thai, which as it’s name suggests, is a martial art originating in Thailand. She was one of five girls training in Las Vegas under Toddy – a nickname given because the teacher’s real name of Thohsaphol Sitiwatjana was too unpronounceable to Westerners! The goal of both Toddy and his students was a trip to Thailand to take on the best local practitioners of the sport. This “documentary” covers both their training and the visit itself, climaxing with Carano’s battle against the Thai champion.

Del Castillo is the undisputed queen of the action telenovela. She made her name as the original “Queen of the South” in one of the most popular entries ever,

Del Castillo is the undisputed queen of the action telenovela. She made her name as the original “Queen of the South” in one of the most popular entries ever,  Professional wrestling is perhaps more international than you’d expect. While traditional territories – USA, Japan, Mexico and the UK – still remain the powerhouses, there is hardly a country in the world without its own local pro federation. But even I had not heard of Ecuador’s cholita luchadoras. Cholita is a term used for the native women there, usually found at the bottom of the social pyramid, both in terms of wealth and education. So the term translates as the “fighting cholitas“, who use pro wrestling as a way out of poverty, and to help them at least approach the average wage there, which is around $270 per month.

Professional wrestling is perhaps more international than you’d expect. While traditional territories – USA, Japan, Mexico and the UK – still remain the powerhouses, there is hardly a country in the world without its own local pro federation. But even I had not heard of Ecuador’s cholita luchadoras. Cholita is a term used for the native women there, usually found at the bottom of the social pyramid, both in terms of wealth and education. So the term translates as the “fighting cholitas“, who use pro wrestling as a way out of poverty, and to help them at least approach the average wage there, which is around $270 per month. That’s par for the course – as another example,

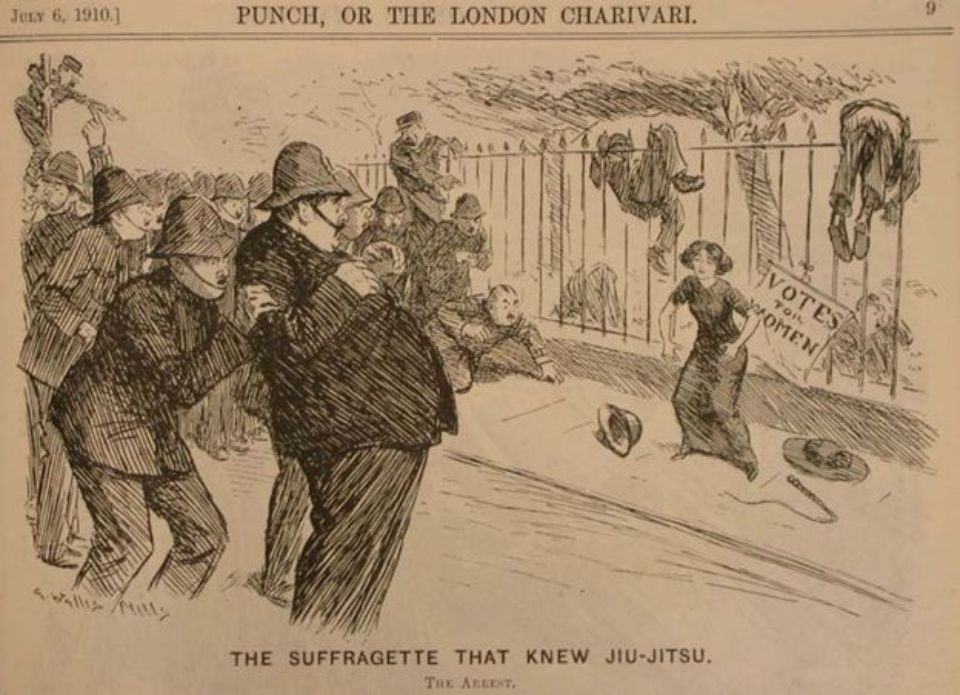

That’s par for the course – as another example,  The most immediate difference any wrestling fan will notice, is the costumes. While in America, wrestlers typically wear a limited amount of tight-fitting clothing, intended not to interfere with their moves, the cholitas come to fight in the traditional native costumes, consisting of multiple layered skirts (typically five or six), and little bowler hats which perch on top of their long, braided hair. [Bonus fact: the angle of the hat indicates marital status] It seems implausible they would be able to do anything requiring significant movement, but you’d be surprised. Also worth noting: the women need particular endurance, due to the altitude. Bolivia’s capital, La Paz, is the highest in the world, and the nearby low-income suburb of El Alto, home of the cholitas, is more elevated still, at over 13,500 feet above sea-level. Simply breathing is hard work, that far up.

The most immediate difference any wrestling fan will notice, is the costumes. While in America, wrestlers typically wear a limited amount of tight-fitting clothing, intended not to interfere with their moves, the cholitas come to fight in the traditional native costumes, consisting of multiple layered skirts (typically five or six), and little bowler hats which perch on top of their long, braided hair. [Bonus fact: the angle of the hat indicates marital status] It seems implausible they would be able to do anything requiring significant movement, but you’d be surprised. Also worth noting: the women need particular endurance, due to the altitude. Bolivia’s capital, La Paz, is the highest in the world, and the nearby low-income suburb of El Alto, home of the cholitas, is more elevated still, at over 13,500 feet above sea-level. Simply breathing is hard work, that far up.

No matter how bad-ass you are, you’ll never attain “13-year-old Mongolian girl, standing astride a mountain, holding the trained golden eagle she raised from a chick, after climbing down a cliff to get it” levels of bad-ass. That’s what we have here, folks, in this documentary about Aisholpan. She’s a Mongolian teenager who wants to become an eagle huntress, a profession traditionally reserved for the male lineage. Her father Rys learned the skills necessary (and, presumably, inherited the really large, very well-padded glove) from his father, and so on.

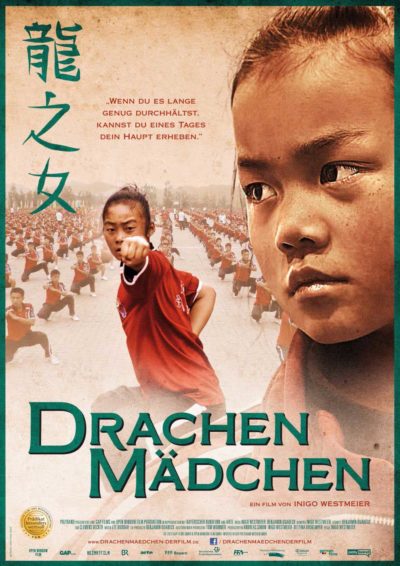

No matter how bad-ass you are, you’ll never attain “13-year-old Mongolian girl, standing astride a mountain, holding the trained golden eagle she raised from a chick, after climbing down a cliff to get it” levels of bad-ass. That’s what we have here, folks, in this documentary about Aisholpan. She’s a Mongolian teenager who wants to become an eagle huntress, a profession traditionally reserved for the male lineage. Her father Rys learned the skills necessary (and, presumably, inherited the really large, very well-padded glove) from his father, and so on. If you’re familiar with Jackie Chan’s life story, you’ll know he (along with fellow future start Sammo Hung and Yuen Biao) was basically brought up in a Peking Opera school, where he learned martial arts and acrobatics as well as theatrical skills. Discipline there was notoriously strict – the film Painted Faces gives a good idea of what it was like. But that was the sixties. Surely no such abusive educational regime exists nowadays?

If you’re familiar with Jackie Chan’s life story, you’ll know he (along with fellow future start Sammo Hung and Yuen Biao) was basically brought up in a Peking Opera school, where he learned martial arts and acrobatics as well as theatrical skills. Discipline there was notoriously strict – the film Painted Faces gives a good idea of what it was like. But that was the sixties. Surely no such abusive educational regime exists nowadays? In February 2002, Ingrid Betancourt was travelling through a rural area of Colombia, as part of her campaign in the presidential election for the Green Party. She was stopped at a road-block run by the Marxist rebel organization, FARC, and when they realized who they had, she and her assistant, Clara Rojas, were kidnapped. Betancourt would spent more than six years of jungle captivity with the guerillas, until she was rescued, in a startling piece of deception, by Colombian military forces. This documentary film tells her story, through archive footage and interviews with Betancourt, Rojas, other kidnappees and some of the FARC members.

In February 2002, Ingrid Betancourt was travelling through a rural area of Colombia, as part of her campaign in the presidential election for the Green Party. She was stopped at a road-block run by the Marxist rebel organization, FARC, and when they realized who they had, she and her assistant, Clara Rojas, were kidnapped. Betancourt would spent more than six years of jungle captivity with the guerillas, until she was rescued, in a startling piece of deception, by Colombian military forces. This documentary film tells her story, through archive footage and interviews with Betancourt, Rojas, other kidnappees and some of the FARC members.