★★

“Long live the new flesh.”

I’m on the fence with regard to the Japanese uber-gore films, most notably, by the Sushi Typhoon studio, which have achieved renown (or infamy) of late. While some (Mutant Girls Squad) are entertaining nonsense, others (Helldriver) are pretty tedious. So, the concept of lower-budget, exploitation-er versions of these, already low-budget exploitation flicks, is a mixed blessing. Enter Zen Pictures, and their formula, which appears to consist of costumed heroines who alternately fight and get tortured. The story here is split into two volumes, but with each barely an hour long and containing plenty of filler, probably better to consider them a single, feature-length entry.

I’m on the fence with regard to the Japanese uber-gore films, most notably, by the Sushi Typhoon studio, which have achieved renown (or infamy) of late. While some (Mutant Girls Squad) are entertaining nonsense, others (Helldriver) are pretty tedious. So, the concept of lower-budget, exploitation-er versions of these, already low-budget exploitation flicks, is a mixed blessing. Enter Zen Pictures, and their formula, which appears to consist of costumed heroines who alternately fight and get tortured. The story here is split into two volumes, but with each barely an hour long and containing plenty of filler, probably better to consider them a single, feature-length entry.

I do like the central story, which is daft as a brush, yet executed with the right level of straight-faced intensity. In order to market his half-human, half-machine cyborgs to the military, Koumoto, chairman of the Dainippon company, comes up with a cunning plan: create a set of female athletes, who will smash all existing records. However, he has forgotten the Japanese Sports Association, under chief Gondo, who don’t take kindly to these performance-enhancing shenanigans. The solution? Naturally, build their own (eco-friendly!) cyborg to fight the Dainippon team. Except, due to an administrative cock-up, the original candidate, Megumi Asaoka (Taki), is accidentally replaced by Ai Asaoka (Noda). Initially, Ai is successful, but after being captured by Koumoto, she is reprogrammed, and her friend Megumi has to battle to rescue Ai.

The first volume is significantly better, though still has its weaknesses, not the least being more evidence that crappy CGI is far less endearing than crappy practical effects – and there’s enough of both to be seen here. However, it whizzes along with sufficient energy, and contains plenty of action, to merit forgiveness for the obvious poverty-row origins, and everyone involved chews scenery to amusing effect. After the break, unfortunately, things slow down, with a pair of lengthy torture sequences which had absolutely no value for me whatsoever, and the fights seemed, to a large extent, repeats of those from the first volume. Both parts also have another severe weakness – taking an idea and running with it, well past the point where it stops being interesting. Case in point: one of the battles includes the participants each releasing a cyborg arm, which then stage their own fight, independently. For 15 seconds, it’s kinda amusing. After a minute, it’s dull. But the film keeps going far beyond that, and there are plenty of similar cases; the surgery which turns Ai into a cyborg is also depicted at far greater length than necessary. Maybe this is some Japanese fetish thing, of which I was previously unaware.

This is definitely a case where less would have been more, and with a more enthusiastic hand on the editor’s knife, this could have become a decent eighty-minute feature – and possibly an even better 50-minute one. Kamikura does often demonstrate an awareness and acceptance of exactly how ludicrous the entire scenario is, and the film is at its best when wholeheartedly embracing its own insanity. For instance, each of the cyborg athletes’ talents is influenced by their sport: Hitomi Oka is a tennis-player, so whacks people with an over-sized, pneumatic racket, and lobs exploding tennis-balls at them. Additional helpings of that kind of imaginative lunacy – and considerably less tied-up schoolgirls being prodded or whipped – would certainly have made for a more entertaining end product.

This is definitely a case where less would have been more, and with a more enthusiastic hand on the editor’s knife, this could have become a decent eighty-minute feature – and possibly an even better 50-minute one. Kamikura does often demonstrate an awareness and acceptance of exactly how ludicrous the entire scenario is, and the film is at its best when wholeheartedly embracing its own insanity. For instance, each of the cyborg athletes’ talents is influenced by their sport: Hitomi Oka is a tennis-player, so whacks people with an over-sized, pneumatic racket, and lobs exploding tennis-balls at them. Additional helpings of that kind of imaginative lunacy – and considerably less tied-up schoolgirls being prodded or whipped – would certainly have made for a more entertaining end product.

Dir: Eiji Kamikura

Star: Ayaka Noda, Arisa Taki, Masahiro Saito, Shinya Nakamura

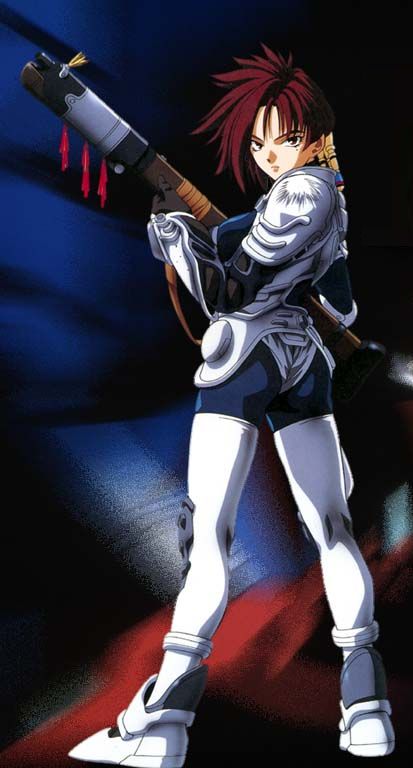

And not a very good movie at that, suffering from such multiple personality disorder, it sometimes feels that two completely different anime were spliced together in some mad scientist’s laboratory. If so, he clearly got bored and drifted off while the project was half complete, because this ends in a way which doesn’t so much suggest another part, as demand it unconditionally. Six years on, that still hasn’t materialized, making this about as appetizing as a half-cooked chicken. Oh, and speaking of mad scientists, there’s one of those in here too.

And not a very good movie at that, suffering from such multiple personality disorder, it sometimes feels that two completely different anime were spliced together in some mad scientist’s laboratory. If so, he clearly got bored and drifted off while the project was half complete, because this ends in a way which doesn’t so much suggest another part, as demand it unconditionally. Six years on, that still hasn’t materialized, making this about as appetizing as a half-cooked chicken. Oh, and speaking of mad scientists, there’s one of those in here too. This doesn’t so much hit the ground running, as plummet into it at top speed, to such an extent I genuinely stopped the film, to check if this was perhaps part two of an ongoing series. It isn’t: it’s just that unconcerned about explanations. What seems to be going on, is a universe where the different dimensions are now connected. Hence, there’s Retro World, Fairy World, Lost World, etc. This offers new criminal possibilities; to counter these, a trans-dimensional police force is also created. One such officer is Ai (Nagasawa), but her mission, to protect a psychic (Takayama) against the terrorist group Doubt is thrown into… Well, doubt after she meets her former partner Yui (Kinoshita), who appears to have thrown her lot in on the side of the villains.

This doesn’t so much hit the ground running, as plummet into it at top speed, to such an extent I genuinely stopped the film, to check if this was perhaps part two of an ongoing series. It isn’t: it’s just that unconcerned about explanations. What seems to be going on, is a universe where the different dimensions are now connected. Hence, there’s Retro World, Fairy World, Lost World, etc. This offers new criminal possibilities; to counter these, a trans-dimensional police force is also created. One such officer is Ai (Nagasawa), but her mission, to protect a psychic (Takayama) against the terrorist group Doubt is thrown into… Well, doubt after she meets her former partner Yui (Kinoshita), who appears to have thrown her lot in on the side of the villains.

2013 was perhaps a landmark for women in action films. with the top slot at the American box-office going to Jennifer Lawrence in Catching Fire. But also present in the top five was this, which kicked Katniss’s arse for critical acclaim, snaring 10 Oscar nominations to Fire’s… Well, none at all, actually. That’s probably a little starker contrast than is accurate – they are respectively 97% and 90% Fresh at Rotten Tomatoes – but it is interesting to compare the two films and their approach. In Gravity, the sex of the lead character simply isn’t very relevant: you could switch it to being a man, and you wouldn’t need to change much, not even the name – Ryan Stone. I’d be unsurprised if told that, like Salt, this was originally written for a male lead. Indeed, it also fails the infamous Bechdel Test of feminism, passing none of its three criteria – though this says more about Bechdel’s uselessness than Gravity, I feel (Run Lola Run also goes 0-for-3, and it’s not the last thing it has in common, as we’ll see).

2013 was perhaps a landmark for women in action films. with the top slot at the American box-office going to Jennifer Lawrence in Catching Fire. But also present in the top five was this, which kicked Katniss’s arse for critical acclaim, snaring 10 Oscar nominations to Fire’s… Well, none at all, actually. That’s probably a little starker contrast than is accurate – they are respectively 97% and 90% Fresh at Rotten Tomatoes – but it is interesting to compare the two films and their approach. In Gravity, the sex of the lead character simply isn’t very relevant: you could switch it to being a man, and you wouldn’t need to change much, not even the name – Ryan Stone. I’d be unsurprised if told that, like Salt, this was originally written for a male lead. Indeed, it also fails the infamous Bechdel Test of feminism, passing none of its three criteria – though this says more about Bechdel’s uselessness than Gravity, I feel (Run Lola Run also goes 0-for-3, and it’s not the last thing it has in common, as we’ll see).

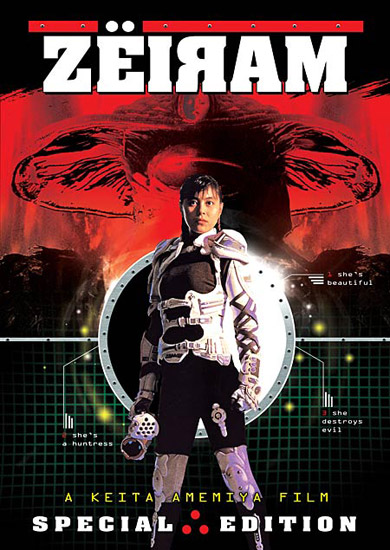

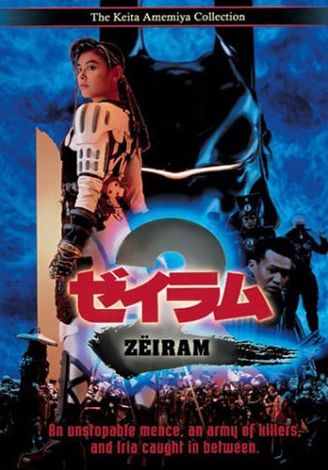

Though released several years later, this is a prequel to the two Zeiram movies, telling the story of the first encounter between Iria (Hisakawa, who was also Sailor Mercury) and Zeiram. At the time, she was an apprentice bounty-hunter, working alongside her brother Gren. They take a mission to rescue a VIP and recover the cargo from a stranded space-ship. However, once there, they discover the “cargo” is actually the alien Zeiram, which a corporation is interested in using as a weapon. The result leaves her brother apparently dead, and Iria now the target for the corporation, who want to hush up their thoroughly-dubious plan, by any means necessary. Fortunately, as well as her own skills, our heroine has the assistance of former rival bounty-hunter, Fujikuro (Chiva), endearing urchin Kei (Kanai), and Bob (Ikeda), a colleague whose consciousness has been turned into an AI.

Though released several years later, this is a prequel to the two Zeiram movies, telling the story of the first encounter between Iria (Hisakawa, who was also Sailor Mercury) and Zeiram. At the time, she was an apprentice bounty-hunter, working alongside her brother Gren. They take a mission to rescue a VIP and recover the cargo from a stranded space-ship. However, once there, they discover the “cargo” is actually the alien Zeiram, which a corporation is interested in using as a weapon. The result leaves her brother apparently dead, and Iria now the target for the corporation, who want to hush up their thoroughly-dubious plan, by any means necessary. Fortunately, as well as her own skills, our heroine has the assistance of former rival bounty-hunter, Fujikuro (Chiva), endearing urchin Kei (Kanai), and Bob (Ikeda), a colleague whose consciousness has been turned into an AI. Zeiram and its sequel, Zeiram 2, both concern a creature which combines all the most unpleasant and lethal features of The Thing with The Terminator. It’s humanoid, at least in the number of functioning limbs, but its head appears almost mushroom shaped – though it’s hard to tell where Zeiram ends and its hat begins, for there’s a second face, embedded in the hat. This is capable of extending on a tentacle, to attack victims, taking in nourishment, and there’s evidence to suggest that it can absorb their DNA and use it to create monsters. Oh, and the rest of it is almost impossible to destroy.

Zeiram and its sequel, Zeiram 2, both concern a creature which combines all the most unpleasant and lethal features of The Thing with The Terminator. It’s humanoid, at least in the number of functioning limbs, but its head appears almost mushroom shaped – though it’s hard to tell where Zeiram ends and its hat begins, for there’s a second face, embedded in the hat. This is capable of extending on a tentacle, to attack victims, taking in nourishment, and there’s evidence to suggest that it can absorb their DNA and use it to create monsters. Oh, and the rest of it is almost impossible to destroy. The sequel, which came out three years later, restores the “i” in the title, which was inexplicably removed from the original for it US release by Fox Lorber. This installment starts off as if it’s going to go in some radically different directions, even if all the main players are back. Iria is seeking an ancient artifact called the Carmarite, and additionally, has a new assistant, but he turns out to be untrustworthy. Meanwhile, a shadowy group has succeeded in regenerating Zeiram as a cyborg warrior (which makes a lot more sense if you’ve seen the anime, and know its origins), bending its will to their needs and turning it into a weapon. While initially successfully, this works about as well as most plans usually do, and it’s not longer before Zeiram is much more a menace than an ally.

The sequel, which came out three years later, restores the “i” in the title, which was inexplicably removed from the original for it US release by Fox Lorber. This installment starts off as if it’s going to go in some radically different directions, even if all the main players are back. Iria is seeking an ancient artifact called the Carmarite, and additionally, has a new assistant, but he turns out to be untrustworthy. Meanwhile, a shadowy group has succeeded in regenerating Zeiram as a cyborg warrior (which makes a lot more sense if you’ve seen the anime, and know its origins), bending its will to their needs and turning it into a weapon. While initially successfully, this works about as well as most plans usually do, and it’s not longer before Zeiram is much more a menace than an ally. “Z is for Zeiram”

“Z is for Zeiram” ★★★½

★★★½ But the central idea is the one of Ripley now being something more than human, and Weaver has a great deal of fun with that, playing as if she’s half a beat ahead of everyone else, and completes her transition by no longer being scared of the aliens. It’s them who need to be scared of her, and again, I’m reminded of Milla Jovovich in the RE series: more than human, and yet, less than human at the same time. There’s even a creature with the proportions the other way round – monster with a touch of human – like Nemesis from RE: Apocalypse, and it was no surprise to read that Paul W.S. Anderson was one of the many directors considered for this (Danny Boyle, Peter Jackson, Bryan Singer and David Croneberg beinh among the others). I briefly drifted off to speculate on the possibility of an Alien vs. Resident Evil cross-over; would probably have been a lot more fun than anything involving Predators.

But the central idea is the one of Ripley now being something more than human, and Weaver has a great deal of fun with that, playing as if she’s half a beat ahead of everyone else, and completes her transition by no longer being scared of the aliens. It’s them who need to be scared of her, and again, I’m reminded of Milla Jovovich in the RE series: more than human, and yet, less than human at the same time. There’s even a creature with the proportions the other way round – monster with a touch of human – like Nemesis from RE: Apocalypse, and it was no surprise to read that Paul W.S. Anderson was one of the many directors considered for this (Danny Boyle, Peter Jackson, Bryan Singer and David Croneberg beinh among the others). I briefly drifted off to speculate on the possibility of an Alien vs. Resident Evil cross-over; would probably have been a lot more fun than anything involving Predators.