★★

“Wings of desire.”

The idea here is considerably stronger than the execution. Police detective Riley Parra (Hassler) works the scummiest part of town, which is ruled by mysterious and possibly legendary figure Marchosias (Landler). However, while working a murder case, Riley discovers the area is, in fact, Ground Zero for an ongoing war between demons and angels. More startlingly yet, she’s directly involved, because she is the “champion” on the side of the angels. This revelation has the potential to destroy the shaky truce which has been in place between the two sides. Riley also has to deal with pesky journalist, Gail Finney (Sirtis, sporting an Australian accent for some reason), and attraction to new medical examiner Dr. Gillian Hunt (Vassey).

The idea here is considerably stronger than the execution. Police detective Riley Parra (Hassler) works the scummiest part of town, which is ruled by mysterious and possibly legendary figure Marchosias (Landler). However, while working a murder case, Riley discovers the area is, in fact, Ground Zero for an ongoing war between demons and angels. More startlingly yet, she’s directly involved, because she is the “champion” on the side of the angels. This revelation has the potential to destroy the shaky truce which has been in place between the two sides. Riley also has to deal with pesky journalist, Gail Finney (Sirtis, sporting an Australian accent for some reason), and attraction to new medical examiner Dr. Gillian Hunt (Vassey).

This is based on a series of books by Geonn Cannon, and is a mixed bag. I like the idea that the police department is entirely staffed by women, and nobody particularly cares. That they all appear to be lesbians? Hmm. Geonn is a male author, I should mention, which makes this… interesting. It’s all very much PG-rated, but really, I feel all the relationship stuff seriously gets in the way of the plot. Not least, because this ends with none of the major threads anywhere close to tied-up. Instead, it finishes with Riley just having solved a murder which doesn’t even take place until 65 minutes into the movie. Originally a webseries, it seems more a pilot than an actual film. Five years later, there’s no continuation, so do not expect resolution.

There are also silly little gaffes, such as Dr. Hunt picking up evidence at a murder scene with her bare hands. Or Riley getting a call and being texted the location of the same murder, then saying, “I’ll be there in 15 minutes” – without looking at her phone. Be where exactly? It’s all minor, but indicative of a rather sloppy approach to film-making. Shame, since the characters here are quite interesting, and the performances are decent. Everyone here seems like they could be a real person, even Marchosias and his outrageously French accent (that actor actually is French, so I’ll let it pass).

It feels fairly pro-religion, both in its central concept and sympathetic presentation of the priest, to whom Riley turns for advice. I’d have liked to have seen more action: I think the only person Riley shoots is her partner – not much of a spoiler, since it happens early on. Oddly, that barely leads to any disciplinary action or investigation, more evidence of the slapdash approach to detail. I do suspect some characters are not what they seem. I think either Riley’s boss, or Gail Finney, are actually agents for Marchosias. The latter would be interesting, being the kind of crusading, anti-police journalist you might expect to be the heroine in another story. Guess we’ll never know. Well, unless I read the novels and… Yeah, I probably wasn’t sufficiently into this to justify the effort there.

Dir: Christin Baker

Star: Marem Hassler, Liz Vassey, Karl E. Landler, Marina Sirtis

I’d not heard of this, and we pleased to find it was directed by Sakamoto, a well-respected action choreographer, best known for Power Rangers, but who also worked on

I’d not heard of this, and we pleased to find it was directed by Sakamoto, a well-respected action choreographer, best known for Power Rangers, but who also worked on  This is another in a recent burst of Thai action heroine movies, including

This is another in a recent burst of Thai action heroine movies, including  A decade after the splattery joy which was

A decade after the splattery joy which was

Daphne Wool (Varela) has finally had enough of her abusive husband, so has killed him, chopping up the corpse and keeping it in a storage locker. Which actually is a good thing, because it turns out he was wanted by the Mob, and there was a price on his head. For their “help” in carrying out the hit, Daphne and pal Tony Steele (Cappello) are rewarded, but things go further. Daphne becomes a full-time assassin for the gangsters, learning to kill with everything from a paper-clip up, while Tony acts as her facilitator. However, they quickly become a liability to the organization, and are given a “poison pill” contract, being sent to kill weapons inventor Vincent McCabe.

Daphne Wool (Varela) has finally had enough of her abusive husband, so has killed him, chopping up the corpse and keeping it in a storage locker. Which actually is a good thing, because it turns out he was wanted by the Mob, and there was a price on his head. For their “help” in carrying out the hit, Daphne and pal Tony Steele (Cappello) are rewarded, but things go further. Daphne becomes a full-time assassin for the gangsters, learning to kill with everything from a paper-clip up, while Tony acts as her facilitator. However, they quickly become a liability to the organization, and are given a “poison pill” contract, being sent to kill weapons inventor Vincent McCabe. Football is known as “The beautiful game,” but you wouldn’t know it based on this documentary, which seems perversely intended to remove anything like that from its topic. It focuses on

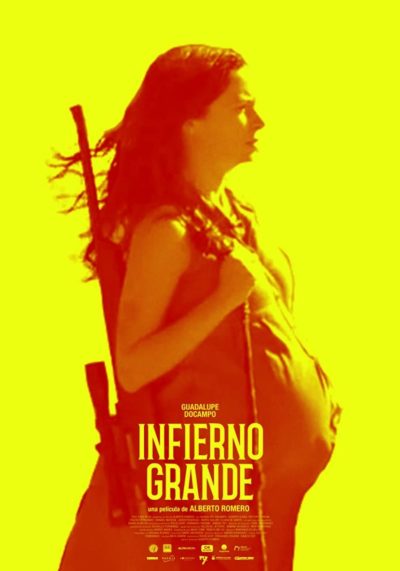

Football is known as “The beautiful game,” but you wouldn’t know it based on this documentary, which seems perversely intended to remove anything like that from its topic. It focuses on  This begins, literally, with a bang. We first meet the heavily pregnant Maria (Docampo), carrying a rifle and preparing to leave her house. A man rises from the floor, and after a struggle for the gun, it goes off, and he drops back down. She hits the road in their pick-up truck, fearful of what she had done, and intending to head back to Naicó, the town where she was born. However, it’s not long before the people she meets on the road, seek to dissuade her from going there. It seems like everyone has a weird story about why her destination is not a good idea, from mysterious lights that abduct you, to a cult of blond people with possible Nazi connections.

This begins, literally, with a bang. We first meet the heavily pregnant Maria (Docampo), carrying a rifle and preparing to leave her house. A man rises from the floor, and after a struggle for the gun, it goes off, and he drops back down. She hits the road in their pick-up truck, fearful of what she had done, and intending to head back to Naicó, the town where she was born. However, it’s not long before the people she meets on the road, seek to dissuade her from going there. It seems like everyone has a weird story about why her destination is not a good idea, from mysterious lights that abduct you, to a cult of blond people with possible Nazi connections. Margo Crane (DelaCerna) has been brought up by her native American father, since her mother walked out on them several years ago. Under his guidance, they have become self-sufficient, and Margo has become a crack shot. However, her creepy uncle ends up having sex with the teenager, an incident for which she gets blamed, ruining her life. She resolves to apply her shooting skills on him, only for the resulting incident to become a tragedy. Margo strikes out on her own up the Stark river, in search of her absent mother. Doing so, she meets a variety of people, then has to try and reconnect with a woman who now has her own life, one not necessarily helped by the unexpected arrival of a teenager.

Margo Crane (DelaCerna) has been brought up by her native American father, since her mother walked out on them several years ago. Under his guidance, they have become self-sufficient, and Margo has become a crack shot. However, her creepy uncle ends up having sex with the teenager, an incident for which she gets blamed, ruining her life. She resolves to apply her shooting skills on him, only for the resulting incident to become a tragedy. Margo strikes out on her own up the Stark river, in search of her absent mother. Doing so, she meets a variety of people, then has to try and reconnect with a woman who now has her own life, one not necessarily helped by the unexpected arrival of a teenager. This documentary is about the field of women in aviation, combining archive footage with interviews, covering the range from those who aspire to fly (giving their Lego aircraft lady pilots!) to those who have been into space, fought combat missions in the Middle East or dodged death in aerobatic displays. There’s not any particular structure to proceedings, choosing instead to bounce around between its topics and subjects. This helps keep things fresh, yet at the cost of any narrative beyond, I guess, “Women can do anything men can”? Which, to be fair, deserves saying in the aviation field particularly: how much strength is needed to handle a joystick?

This documentary is about the field of women in aviation, combining archive footage with interviews, covering the range from those who aspire to fly (giving their Lego aircraft lady pilots!) to those who have been into space, fought combat missions in the Middle East or dodged death in aerobatic displays. There’s not any particular structure to proceedings, choosing instead to bounce around between its topics and subjects. This helps keep things fresh, yet at the cost of any narrative beyond, I guess, “Women can do anything men can”? Which, to be fair, deserves saying in the aviation field particularly: how much strength is needed to handle a joystick?