★★★½

“Parental advisory, to put it mildly.”

This is not an easy film to watch. The easily-offended should stay away. Indeed, even the hard to offend, which include myself, may find it rough going. To give you some idea, the opening scene is set in a 1978 Chilean torture chamber where a political dissident is being interrogated. When she won’t talk, her son is drugged and forced to rape his own mother. It actually goes on to get worse still, but that’ll give you some idea. In terms of disturbing opening scenes, I can’t think of many equivalents.

This is not an easy film to watch. The easily-offended should stay away. Indeed, even the hard to offend, which include myself, may find it rough going. To give you some idea, the opening scene is set in a 1978 Chilean torture chamber where a political dissident is being interrogated. When she won’t talk, her son is drugged and forced to rape his own mother. It actually goes on to get worse still, but that’ll give you some idea. In terms of disturbing opening scenes, I can’t think of many equivalents.

Fast forward to 2011, and four young women are on their way for a quiet weekend in a country house owned by one’s uncle. An unfortunate stop for directions in a local dive-bar puts them on the radar of Juan (Antivilo) and his son, Mario (Ríos). The former was the teenage boy of the opening sequence, and was clearly broken beyond repair by those and other events. He has passed that damage on to Mario, and the pair now form a father-son duo of staggering repugnance. When they subsequently show up on the doorstep, our four heroines are in for a very, very unpleasant night. But when they learn Juan has turned his attentions to pre-pubescent local girl, Yoya, they decide something must be done, and take the fight to Juan and Mario.

It’s brutally unpleasant stuff, with some (literally) mind-blowingly gory effects. But it’s acted and assembled well enough that it can’t be written off as mere torture porn, and some radical switches in tone actually work in its favour. For example, after the opening scene, we cut to some intense lesbian canoodling, provoking cinematic cognitive dissonance which is disturbing yet effective. And importantly, it’s not without a point. In that area, it’s like A Serbian Film, which used its cinematic atrocities as a parable about the break-up of Yugoslavia. I’d actually say this was rather more successful in terms of getting its message over, about the impact of the tyrannical Allende regime of the seventies and its impact over the decades.

The carnage likely reaches its peak near the middle when everyone returns to the bar, for a fight of disturbing savagery, even by this movie’s standards, which also affirms Juan’s status as completely above the law in the local community. The final battle, I have to say, did come across as rather confused in comparison, likely hindered by lighting which barely reached the level of murky. As a result, on more than one occasion, I went “Hang on, aren’t they dead already?”Considering how coolly clinical Rojas’s camera was in capturing the previous unpleasantness, this was disappointing.

If there’s a message here, it’s the one written by Edward Burke: “The only thing necessary for the triumph of evil is for good men to do nothing.” Or women, in this case, with Andrea (Martin) taking the lead. She’s an interesting character, with a certain standard of morality: for instance, she doesn’t like her sister’s girlfriend, though it’s unclear whether this is because of gender or personality. It’s Andrea who increasingly occupies centre-stage as events unfold, and occupies the film’s final frame. Though let’s just say, it’s not exactly what you would call a happy ending, even if there is some degree of catharsis to be found. It’s probably even harder to forget than to watch.

Dir: Lucio A. Rojas.

Star: Catalina Martin, Daniel Antivilo, Macarena Carrere, Felipe Ríos

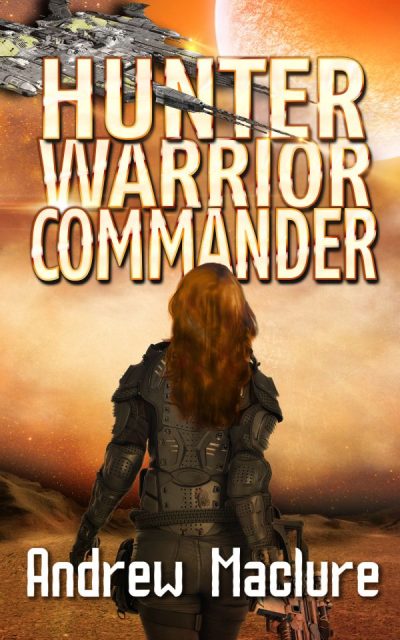

There is an interesting set-up here: unfortunately, it’s one which truly doesn’t get developed far enough. Elen-Ai is a 21-year-old woman, who has been brought up since birth to be an assassin for hire, part of “The Family.” Her latest commission is a little different: it’s not to kill, but to protect. For she is hired to make sure that Gidyon, the teenage son of Latana, Queen of the Second Country, stays alive. This is a matriarchal society, where power passes down the female side. But Latana has only her son, and is set to upset the traditional apple-cart by proclaiming Gidyon as her heir apparent. This decision will potentially be rejected by some among the seven clans who comprise the queendom, and may make him a target for those who’d rather see him out of the way. Hence, Elen-Ai’s presence, to make sure that doesn’t happen, as he begins a national tour around their estates, seeking support for his position.

There is an interesting set-up here: unfortunately, it’s one which truly doesn’t get developed far enough. Elen-Ai is a 21-year-old woman, who has been brought up since birth to be an assassin for hire, part of “The Family.” Her latest commission is a little different: it’s not to kill, but to protect. For she is hired to make sure that Gidyon, the teenage son of Latana, Queen of the Second Country, stays alive. This is a matriarchal society, where power passes down the female side. But Latana has only her son, and is set to upset the traditional apple-cart by proclaiming Gidyon as her heir apparent. This decision will potentially be rejected by some among the seven clans who comprise the queendom, and may make him a target for those who’d rather see him out of the way. Hence, Elen-Ai’s presence, to make sure that doesn’t happen, as he begins a national tour around their estates, seeking support for his position. There’s a fascinating idea at the core here. Namely, that vampires were created by God, in order to mitigate mankind’s sin by preying on the most evil examples of humanity. They’re effectively angelic enforcers. The potential in this is great. The execution, however… Well, it largely comes down to two such vampire/angels sitting around a gas station for the majority of the running time. This isn’t the only aspect which is poorly considered. It starts in 1969, when lesbian couple Brooke (Lahiri) and Rhea (Monk) are at a New Year’s party. Brooke kills a rapist, stabbing him (literally) 87 times, and the pair then flee. In the desert, they are visited by God (model Angela Lindvall), who makes Rhea into one of her enforcers.

There’s a fascinating idea at the core here. Namely, that vampires were created by God, in order to mitigate mankind’s sin by preying on the most evil examples of humanity. They’re effectively angelic enforcers. The potential in this is great. The execution, however… Well, it largely comes down to two such vampire/angels sitting around a gas station for the majority of the running time. This isn’t the only aspect which is poorly considered. It starts in 1969, when lesbian couple Brooke (Lahiri) and Rhea (Monk) are at a New Year’s party. Brooke kills a rapist, stabbing him (literally) 87 times, and the pair then flee. In the desert, they are visited by God (model Angela Lindvall), who makes Rhea into one of her enforcers. “Guess who’s back, back again. Jadey’s back, tell a friend…” Okay, that’s as close as you’re ever going to get as a rap from me. But I was genuinely delighted to see this stared Jade Leung, who was perhaps the

“Guess who’s back, back again. Jadey’s back, tell a friend…” Okay, that’s as close as you’re ever going to get as a rap from me. But I was genuinely delighted to see this stared Jade Leung, who was perhaps the  Dear god, this is tedious. It takes forever for anything to happen, and when it does, the impact is less than overwhelming. Ronnie Price (Pearson, occupying territory somewhere between Angelina Jolie in Girl, Interrupted and Michelle Rodriguez) is a former GI, suffering from PTSD after three tours in the Middle East, who took to “self-medicating” herself with heroin in an attempt to deal with what she went through. This doesn’t do too much for her anger issues, and after one brush with the police, she’s made to choose between prison and a spell in a remote, women-only rehab facility. Reluctantly, she chooses the latter, though it’s not long before her PTSD flashbacks kick in, and threaten to make her stay a brief one.

Dear god, this is tedious. It takes forever for anything to happen, and when it does, the impact is less than overwhelming. Ronnie Price (Pearson, occupying territory somewhere between Angelina Jolie in Girl, Interrupted and Michelle Rodriguez) is a former GI, suffering from PTSD after three tours in the Middle East, who took to “self-medicating” herself with heroin in an attempt to deal with what she went through. This doesn’t do too much for her anger issues, and after one brush with the police, she’s made to choose between prison and a spell in a remote, women-only rehab facility. Reluctantly, she chooses the latter, though it’s not long before her PTSD flashbacks kick in, and threaten to make her stay a brief one. A woman (Butler) agrees to take part in a contest. live-streamed for betting purposes, where 20 players are put through a series of tests, designed to push them to the physical and mental breaking point, with the (literally) last person standing getting a million dollars. Her only associate is the Game Master (Fuertes), who oversees the challenges and relays the results from the other location to her. Initially, it seems like he is on her side, cheerleading and encouraging her. But the further into the event she proceeds, the more questionable his actions become, to the point where she begins to doubt everything he tells her.

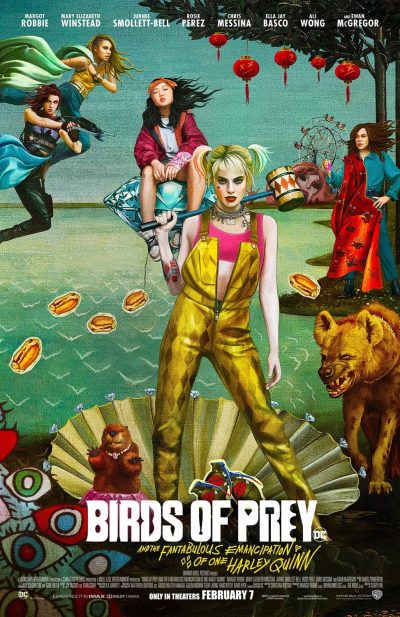

A woman (Butler) agrees to take part in a contest. live-streamed for betting purposes, where 20 players are put through a series of tests, designed to push them to the physical and mental breaking point, with the (literally) last person standing getting a million dollars. Her only associate is the Game Master (Fuertes), who oversees the challenges and relays the results from the other location to her. Initially, it seems like he is on her side, cheerleading and encouraging her. But the further into the event she proceeds, the more questionable his actions become, to the point where she begins to doubt everything he tells her. Or, to give this its full, rather misguided name: Birds of Prey (and the Fantabulous Emancipation of One Harley Quinn). I am not convinced that films are improved by giving them gimmick titles including made-up words. It smacks rather of desperation on the part of the makers. Though this is… alright. It did not actively annoy me in quite the same way

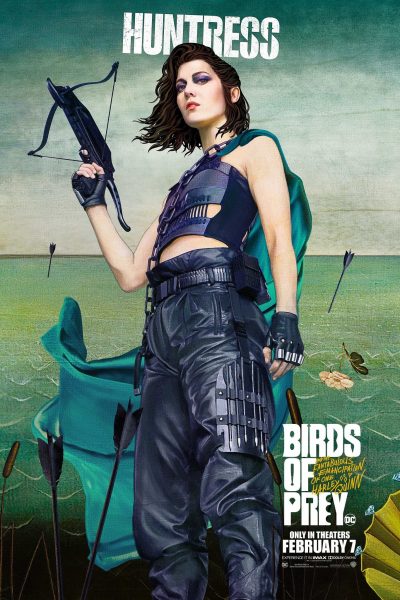

Or, to give this its full, rather misguided name: Birds of Prey (and the Fantabulous Emancipation of One Harley Quinn). I am not convinced that films are improved by giving them gimmick titles including made-up words. It smacks rather of desperation on the part of the makers. Though this is… alright. It did not actively annoy me in quite the same way  The action is a bit of a mixed bag. There are a couple of very good brawls for Harley, most notably one in a police evidence warehouse (even if the cops seem curiously unwilling to draw and use their firearms. What is this, the United Kingdom?) where Robbie and her stunt doubles get to showcase some stellar moves. But the final fight has much the same problem as the plot in general. In trying to make sure each of the four fighting leads get their chance to shine (Cassandra basically cowers in a corner for the duration of it), the climax basically succeeds in selling all of them short. There is quite a nice “funhouse” atmosphere there, since it takes place in an abandoned amusement park, though it feels like some of the potential wasn’t fully developed.

The action is a bit of a mixed bag. There are a couple of very good brawls for Harley, most notably one in a police evidence warehouse (even if the cops seem curiously unwilling to draw and use their firearms. What is this, the United Kingdom?) where Robbie and her stunt doubles get to showcase some stellar moves. But the final fight has much the same problem as the plot in general. In trying to make sure each of the four fighting leads get their chance to shine (Cassandra basically cowers in a corner for the duration of it), the climax basically succeeds in selling all of them short. There is quite a nice “funhouse” atmosphere there, since it takes place in an abandoned amusement park, though it feels like some of the potential wasn’t fully developed.

This was a genuine and pleasant surprise. The original release was pushed back due to some severe controversy: not many films get Tweeted about by the President of the United States, who stated this was “made in order to inflame and cause chaos.” Needless to say, the studio ended up riding that publicity when the movie eventually came out. The current pandemic ended up trumping that (pun intended), so the film hit the home markets, just a week after its theatrical release. To my surprise, it’s considerably more nuanced than the “Red State vs. Blue State” concept I expected. And Gilpin has clearly put her GLOW training to good use, becoming quite the thirty-something bad-ass here.

This was a genuine and pleasant surprise. The original release was pushed back due to some severe controversy: not many films get Tweeted about by the President of the United States, who stated this was “made in order to inflame and cause chaos.” Needless to say, the studio ended up riding that publicity when the movie eventually came out. The current pandemic ended up trumping that (pun intended), so the film hit the home markets, just a week after its theatrical release. To my surprise, it’s considerably more nuanced than the “Red State vs. Blue State” concept I expected. And Gilpin has clearly put her GLOW training to good use, becoming quite the thirty-something bad-ass here. This may be a first, in that the heroine here is non-human – contrary to what you (and, indeed, I!) might expect from the cover. I think I may have covered various crypto-humans before, such as vampires or elves. But this is likely the first entirely alien species. I began to suspect on page 1, when I read that Sah Lee “sank her pin-sharp teeth through the thick fur of the calf’s throat, and tasted the sweet metallic tang of its young blood.” This is clearly not your average twelve-year-old. And so it proves. The story really kicks under way two years later, when Sah Lee leaves her rural village on the planet of Aarn to attend school in the city of Aa Ellet.

This may be a first, in that the heroine here is non-human – contrary to what you (and, indeed, I!) might expect from the cover. I think I may have covered various crypto-humans before, such as vampires or elves. But this is likely the first entirely alien species. I began to suspect on page 1, when I read that Sah Lee “sank her pin-sharp teeth through the thick fur of the calf’s throat, and tasted the sweet metallic tang of its young blood.” This is clearly not your average twelve-year-old. And so it proves. The story really kicks under way two years later, when Sah Lee leaves her rural village on the planet of Aarn to attend school in the city of Aa Ellet. When I settled in to view this, I didn’t realize it starred Weaving, who was the best thing about the very entertaining

When I settled in to view this, I didn’t realize it starred Weaving, who was the best thing about the very entertaining