Literary rating: ★★★½

Kick-butt quotient: ☆☆½

This SF novel takes place in the future where the human Commonwealth is engaged in a brutal space war against the militaristic Shrehari Empire – imagine Klingons on krack, perhaps. They have superior technology, but humanity’s ability to think outside the box and improvise has helped level the playing field. Siobhan Dunmoore has just survived – emphasis on “just” – a battle against the Imperial cruiser Tol Vakash of Captain Brakal, forcing him to retreat by attempting a kamikaze crash of her badly-damaged craft into his. As a “reward”, she is assigned command of the Stingray, a craft with a bad reputation. Its previous captain is now facing a Disciplinary Board, and the crew are barely even trying. It seems Dunmoore has been set up to fail, and she’ll need to overcome resistance from enemies both domestic and alien, as well as overt and covert, before she can even think about going another round with Captain Brakal.

This SF novel takes place in the future where the human Commonwealth is engaged in a brutal space war against the militaristic Shrehari Empire – imagine Klingons on krack, perhaps. They have superior technology, but humanity’s ability to think outside the box and improvise has helped level the playing field. Siobhan Dunmoore has just survived – emphasis on “just” – a battle against the Imperial cruiser Tol Vakash of Captain Brakal, forcing him to retreat by attempting a kamikaze crash of her badly-damaged craft into his. As a “reward”, she is assigned command of the Stingray, a craft with a bad reputation. Its previous captain is now facing a Disciplinary Board, and the crew are barely even trying. It seems Dunmoore has been set up to fail, and she’ll need to overcome resistance from enemies both domestic and alien, as well as overt and covert, before she can even think about going another round with Captain Brakal.

I felt the most interesting section of this was following Dunmoore as she attempted to lick her crew and the Stingray back into a shape, where they could survive an encounter with the Shrehari. Both of them are in need of a lot of work. The former are utterly demoralized after events under the previous captain (including a number of suspicious deaths), and the latter has been short-changed on supplies and resources, to the point it’s largely held together with sticks and wire. Fixing them require their new captain to use a lot of psychology, both in order to get the crew to trust her, and extract the necessary materials from the Commonwealth and its bureaucracy. It works almost as a “how-to” manual for aspiring leaders, and even if that’s not exactly me, still makes for an engaging read. I also liked the very final face-off between Dunmoore and Brakal, their two ships edging round the perilous environment of an asteroid field, where Stingray‘s manoeuvrability gives it an edge.

However, in between the Stingray taking off and the last battle, the book struggles with its descriptive passages. There is a large chunk taking place in hyperspace, and Thomson never manages to make clear the rules which apply here, resulting in the discussion of “jumps” and “bubbles” failing to make sense. Worse, this brings the pace of the book to a halt, with entire pages you find yourself barely skim-reading. There’s also rather too extended of a coda after the battle, as the book tries to tie up a lot of loose ends – mostly ones we never particularly cared about to begin with. On the other hand, I did appreciate the effort put into making Brakal an interesting adversary, with his own set of motivations. He and Dunmoore represent the book’s greatest strengths, and it’s at its best when concentrating on them. If subsequent volumes do that, I’d be tempted to try them.

Author: Eric Thomson

Publisher: Sanddiver Books, available through Amazon, both as a paperback and an e-book

1 of 7 in the Siobhan Dunmoore series.

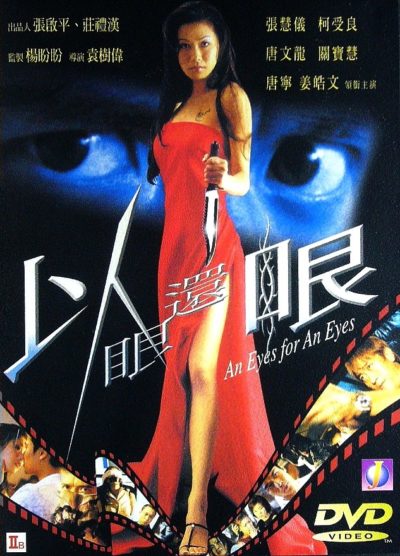

I have seen bad movies before. I have seen Chinese movies before. But I have never before seen such a bad Chinese movie. Really, their action films are usually at least somewhat competent: even the dreadful work of the notorious Godfrey Ho usually had something of… well, interest, if not perhaps quality to offer. This, however? Utterly appalling, with close to no redeeming features. One anecdote should give you some idea of what I mean. When our daughter was 12, she and her little friend borrowed the camcorder and made a 10-minute action movie, mostly taking place in the garage. I am 100% serious when I say it had significantly better fight choreography than this, and the other elements which go into the film are of little if any higher standard.

I have seen bad movies before. I have seen Chinese movies before. But I have never before seen such a bad Chinese movie. Really, their action films are usually at least somewhat competent: even the dreadful work of the notorious Godfrey Ho usually had something of… well, interest, if not perhaps quality to offer. This, however? Utterly appalling, with close to no redeeming features. One anecdote should give you some idea of what I mean. When our daughter was 12, she and her little friend borrowed the camcorder and made a 10-minute action movie, mostly taking place in the garage. I am 100% serious when I say it had significantly better fight choreography than this, and the other elements which go into the film are of little if any higher standard. One of the earliest films directed by Roger Corman, it’d be a major stretch to call this a good film, yet I can’t deny I found it entertaining. It definitely has better female characters than most movies of the mid-fifties. Four women break out of jail and head into the swamps, in search of stolen diamonds which were previously hidden in the Louisiana swamps. Except, one of them is an undercover police officer, Lee Hampton (Mathews), who had been inserted into prison to join the gang and lead the escape, in the hope of recovering the loot. After the car breaks down, they hijack a boat owned by an oil prospector, Bob, and his girlfriend, taking them hostage as they head deeper into the bayou.

One of the earliest films directed by Roger Corman, it’d be a major stretch to call this a good film, yet I can’t deny I found it entertaining. It definitely has better female characters than most movies of the mid-fifties. Four women break out of jail and head into the swamps, in search of stolen diamonds which were previously hidden in the Louisiana swamps. Except, one of them is an undercover police officer, Lee Hampton (Mathews), who had been inserted into prison to join the gang and lead the escape, in the hope of recovering the loot. After the car breaks down, they hijack a boat owned by an oil prospector, Bob, and his girlfriend, taking them hostage as they head deeper into the bayou. This felt oddly familiar, like I had watched it before. One scene in particular – a maintenance man comes to replace a light-bulb, only to become an apparent threat – had me

This felt oddly familiar, like I had watched it before. One scene in particular – a maintenance man comes to replace a light-bulb, only to become an apparent threat – had me  This is not to be confused with the rather higher profile i.e. it’s available on Netflix, Japanese film with the same title, made the same year, and covering a not dissimilar theme. Both are about a woman who is prepared to commit murder, in order to save their best friend from an abusive relationship. However, after the killing in question, the films take divergent paths. The Japflix version becomes a road-trip movie, with the killer and her friend going on the run. This, however, focuses heavily on the killer, whose already fragile mental state falls apart completely, after she discovers that things weren’t quite as she had been led to believe. It’s not her first time at the homicide rodeo either.

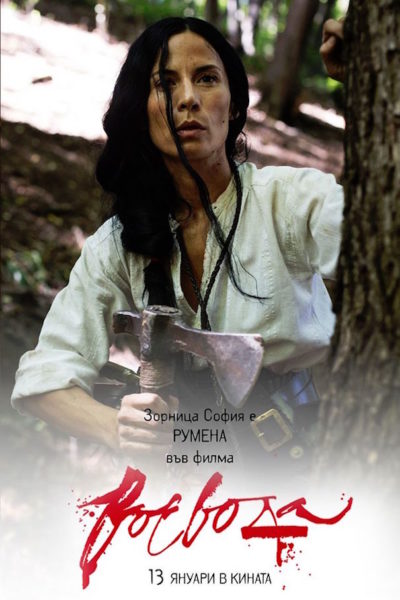

This is not to be confused with the rather higher profile i.e. it’s available on Netflix, Japanese film with the same title, made the same year, and covering a not dissimilar theme. Both are about a woman who is prepared to commit murder, in order to save their best friend from an abusive relationship. However, after the killing in question, the films take divergent paths. The Japflix version becomes a road-trip movie, with the killer and her friend going on the run. This, however, focuses heavily on the killer, whose already fragile mental state falls apart completely, after she discovers that things weren’t quite as she had been led to believe. It’s not her first time at the homicide rodeo either. Well, at the very least, we get to cross another country off the map, in the Action Heroine Atlas. This comes from Bulgaria, and seems to have been a labour of love for Sophia, who co-wrote, directed, produced and starred in it (her daughter plays the younger version of the lead). You don’t see that often, especially in our chosen field. Yet I suspect it could end up having caused more problems than it solves. I’ve often found that films where one person wears so many hats, end up being too “close” to be entirely successful. By which I mean, the maker is so involved they can’t see the flaws, when another pair of eyes might have been able to identify and correct these issues.

Well, at the very least, we get to cross another country off the map, in the Action Heroine Atlas. This comes from Bulgaria, and seems to have been a labour of love for Sophia, who co-wrote, directed, produced and starred in it (her daughter plays the younger version of the lead). You don’t see that often, especially in our chosen field. Yet I suspect it could end up having caused more problems than it solves. I’ve often found that films where one person wears so many hats, end up being too “close” to be entirely successful. By which I mean, the maker is so involved they can’t see the flaws, when another pair of eyes might have been able to identify and correct these issues. I am, probably, biased here. Scottish action heroines are pretty rare, to the point I am hard pushed to think of a single one I’ve covered previously, in the twenty years I’ve been running this domain. [I just made myself feel

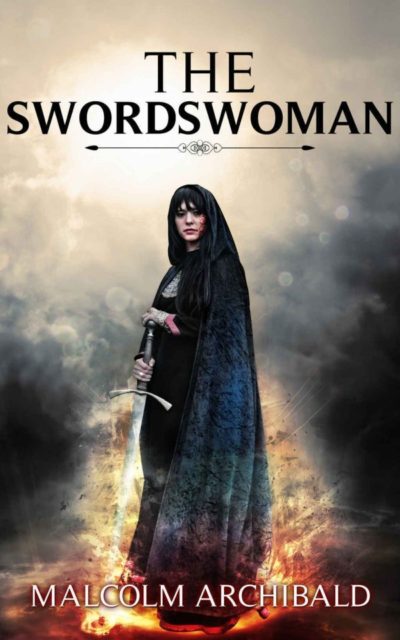

I am, probably, biased here. Scottish action heroines are pretty rare, to the point I am hard pushed to think of a single one I’ve covered previously, in the twenty years I’ve been running this domain. [I just made myself feel  That peace is shattered when someone is washed up on the Western Isles island of Dachaigh where 20-year-old Melcorka lives with her mother. It turns out the Norse are invading, and the king must be notified of the threat. Melcorka and the rest of her clan head towards the capital, only to arrive too late: the army of Alba (as Scotland was then called) has been routed and the nobles scattered. However, Melcorka has a destiny to fulfill… And also inherits a large sword, Defender, with a history dating back centuries, whose powers transform her into the titular character. It’s up to her to rally forces, including the ferocious Picts from the North, to take on the invaders, and send them back across the North Sea to Scandinavia.

That peace is shattered when someone is washed up on the Western Isles island of Dachaigh where 20-year-old Melcorka lives with her mother. It turns out the Norse are invading, and the king must be notified of the threat. Melcorka and the rest of her clan head towards the capital, only to arrive too late: the army of Alba (as Scotland was then called) has been routed and the nobles scattered. However, Melcorka has a destiny to fulfill… And also inherits a large sword, Defender, with a history dating back centuries, whose powers transform her into the titular character. It’s up to her to rally forces, including the ferocious Picts from the North, to take on the invaders, and send them back across the North Sea to Scandinavia. This opens with a scene that is almost a direct life from the similarly titled

This opens with a scene that is almost a direct life from the similarly titled

I came into this somewhat braced, given its 3.0 IMDb rating, and reviews which tended to be scathing e.g. proclaiming “This May Be The WORST Movie I’ve Ever Seen!” While it’s clearly not

I came into this somewhat braced, given its 3.0 IMDb rating, and reviews which tended to be scathing e.g. proclaiming “This May Be The WORST Movie I’ve Ever Seen!” While it’s clearly not