Literary rating: ★★★★★

Kick-butt quotient: ☆☆

Having started our acquaintance with the Ladies Shooting Club trilogy last year with the third book, The Blacksmith’s Bravery (long story), my wife Barb and I are now reading the other two volumes in order. Neither of us were disappointed in this one! My reviewing it here was a happy surprise. Although the covers of all three books feature gun-toting women, and a basic plot current of the trilogy is women learning to take responsibility for defending themselves and others, the heroine of the third book wasn’t actually called on to engage in any gun-fighting action. So I assumed the same would be the case here. But [at the risk of a mild “spoiler” –though for fans of this site, this will add interest rather than spoil it :-)], in this series opener, our heroine does need to step up to the plate with a Winchester. (Contrary to many fictional and movie depictions, rifles were used more for serious shooting in the Old West than six-guns). Despite that difference, though, both books have a lot of similarity in tone, content and style. Since I gave the concluding volume five stars on Goodreads, that’s a good thing!

Having started our acquaintance with the Ladies Shooting Club trilogy last year with the third book, The Blacksmith’s Bravery (long story), my wife Barb and I are now reading the other two volumes in order. Neither of us were disappointed in this one! My reviewing it here was a happy surprise. Although the covers of all three books feature gun-toting women, and a basic plot current of the trilogy is women learning to take responsibility for defending themselves and others, the heroine of the third book wasn’t actually called on to engage in any gun-fighting action. So I assumed the same would be the case here. But [at the risk of a mild “spoiler” –though for fans of this site, this will add interest rather than spoil it :-)], in this series opener, our heroine does need to step up to the plate with a Winchester. (Contrary to many fictional and movie depictions, rifles were used more for serious shooting in the Old West than six-guns). Despite that difference, though, both books have a lot of similarity in tone, content and style. Since I gave the concluding volume five stars on Goodreads, that’s a good thing!

In 1885 small-town Idaho, young Gert Dooley keeps house for her widowed brother, the town’s gunsmith. One thing she can do to help him is test fire the guns he repairs; and she’s gotten to be a crack shot over the years of doing this. When the town’s longtime sheriff is murdered in his office (the titular sheriff is his replacement), the usually quiet community is spooked; and a widowed storekeeper friend asks Gert to teach her how to use her late husband’s Colt, in case she needs it to protect herself or her business. There’s initially no thought of creating a club as such; but as other crimes follow and other women join in the lessons, the Ladies Shooting Club takes shape. Reactions among the community’s menfolk aren’t uniformly supportive –but not uniformly hostile either; stereotypical role expectations of female helplessness weren’t so ingrained in the late 19th-century West as they’d become later.

Despite the historical setting, the issue the novel poses is very contemporary, and hotly debated even today. Male chauvinists tend to see any use of weapons by females as transgressive of patriarchal norms. And while all feminists believe in “empowerment” for women in some sense, many of them either feel that pacifism is ideologically essential to true feminism, or believe that the State and its agents have an absolute monopoly on legitimate use of lethal force, which renders use of a gun for self-defense by ordinary citizens as nearly as bad as using it to attack an innocent. But another strand of feminism rejects that thinking, and views responsible and educated gun ownership as a legitimate tool of women’s empowerment. It’s not hard to deduce from this book what view of that matter Davis takes.

There’s nothing tract-like about this novel, however, any messages emerge naturally from the story itself. Christian faith plays a role in the lives of Gert and other characters, and of the town –the coming of a preacher and his wife to form a nondenominational community church is an important event, as it really was in many Western communities, where organized religion came more slowly than it did in the more easily-settled Eastern states– but the author isn’t “preachy” in her handling of this. The club is also a vehicle for creating female camaraderie and friendship that crosses social divides set by class, religion, and Victorian attitudes (it’ll eventually include both the preacher’s wife and a saloon owner and her girls), and some characters will have lessons to learn in that area.

But the main focus is on the question of what’s behind the sudden rash of arson and violence in the community. I’d describe this as a Western (and there’s horses, guns, a posse, and gun-play at the end), but it embodies very real characteristics of the mystery genre as well. (While I guessed the identity of the villain early on, I’m not sure many readers would –and you might have fun testing your own wits!) And in the background, we have regard and respect growing into love between a worthy man and woman.

Since this was the second book we read of the series, as Barb said, it was “like visiting old friends.” I’d recommend to new readers, though, that they read the books in order. And for us, it’s now on to our third book (which is actually the trilogy’s second), The Gunsmith’s Gallantry!

Author: Susan Page Davis

Publisher: Barbour Publishing, available through Amazon, both for Kindle and as a printed book.

A version of this review previously appeared on Goodreads.

One of the common problems I’ve found with fantasy novels is establishing the universe. It’s clearly going to be very different from the reader’s, and the author needs to get them up to speed on how things work in the book’s setting. If this isn’t done quickly and effectively, the reader can be left floundering in a world they know nothing about. Robinson uses a neat trick to get around this. His heroine, Loren, basically knows nothing about it either, because she has been brought up in a remote rural area. Virtually all she knows about life outside the woods comes from tales told to her by an itinerant tinker, and her dreams of becoming a heroic thief seem no more than fantasies.

One of the common problems I’ve found with fantasy novels is establishing the universe. It’s clearly going to be very different from the reader’s, and the author needs to get them up to speed on how things work in the book’s setting. If this isn’t done quickly and effectively, the reader can be left floundering in a world they know nothing about. Robinson uses a neat trick to get around this. His heroine, Loren, basically knows nothing about it either, because she has been brought up in a remote rural area. Virtually all she knows about life outside the woods comes from tales told to her by an itinerant tinker, and her dreams of becoming a heroic thief seem no more than fantasies. It’s probably worth noting that although this is Volume 1 in the somewhat clunkily-named “Dragon’s Gift: The Protector” series, it follows in the wake of two other Dragon’s Gift threads by the same author, The Huntress and The Seeker. While you don’t need to have read those to enjoy this, it does explain a structure, which could seem somewhat odd. For the volume sets up a trio of treasure-hunting magicians – Cass, Del and Nix – then all but discards the first two and concentrates heavily on Nix. Turns out Cass and Del were the subjects of the Huntress and Seeker sagas respectively, and the Protector gives Nix her turn in the spotlight. This is why some aspects, such as the shop run by the three women, seems more than a bit undeveloped: I presume they were featured in the ten or so previous volumes set in the same world.

It’s probably worth noting that although this is Volume 1 in the somewhat clunkily-named “Dragon’s Gift: The Protector” series, it follows in the wake of two other Dragon’s Gift threads by the same author, The Huntress and The Seeker. While you don’t need to have read those to enjoy this, it does explain a structure, which could seem somewhat odd. For the volume sets up a trio of treasure-hunting magicians – Cass, Del and Nix – then all but discards the first two and concentrates heavily on Nix. Turns out Cass and Del were the subjects of the Huntress and Seeker sagas respectively, and the Protector gives Nix her turn in the spotlight. This is why some aspects, such as the shop run by the three women, seems more than a bit undeveloped: I presume they were featured in the ten or so previous volumes set in the same world. My preferred format for reading is paper; and that’s the only format I support financially, since the only language Big Publishing understands is dollars and cents. Even for a reader like myself, though, e-books have their uses. Writers can offer particular books for free in that format, and that makes it possible to read them first in order to check the quality before you buy the paper edition. And sometimes that opportunity saves you money that would have been wasted if you’d taken a chance on the paper book to begin with! For me, this series opener (which Brown makes available free in e-book format on a permanent basis) was one of those books I was thankful I didn’t have to spend money on, which I’d have regretted.

My preferred format for reading is paper; and that’s the only format I support financially, since the only language Big Publishing understands is dollars and cents. Even for a reader like myself, though, e-books have their uses. Writers can offer particular books for free in that format, and that makes it possible to read them first in order to check the quality before you buy the paper edition. And sometimes that opportunity saves you money that would have been wasted if you’d taken a chance on the paper book to begin with! For me, this series opener (which Brown makes available free in e-book format on a permanent basis) was one of those books I was thankful I didn’t have to spend money on, which I’d have regretted. The principal problem I had here was that the plotting is simply not well thought out, and not convincing. One could argue that the essential premise is far-fetched; but I was okay with suspending disbelief that far. (Whether or not black ops organizations would hire a single mom with kids is a matter of speculation, since real life organizations like this don’t publicize their personnel policies. :-) ) But even within the premise Brown creates, much of her plotting simply doesn’t stand examination. Some of the major actions by the villain(s) are at cross-purposes with some of their other major actions; several events that take place here would involve the police in the story, at a level that couldn’t be ignored, but there’s no indication of that here; Donna’s reasoning for one major decision is weak and unconvincing; and Acme (the company she works for) would be much more actively involved in the decision-making at the end, not passive as it is here. Also, characters could not realistically suddenly just shrug off previously incapacitating wounds (which happens here twice), and there are other significant logical slips that took me out of the story. The author writes prolifically, but she apparently wrote this novel too quickly to take her craftsmanship in plotting seriously, or to put any real thought behind it. (That’s a real shame.)

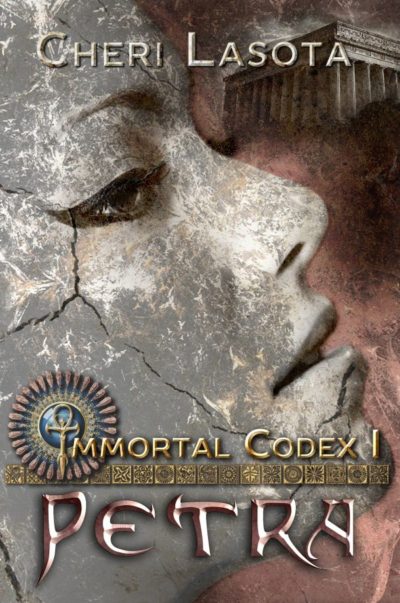

The principal problem I had here was that the plotting is simply not well thought out, and not convincing. One could argue that the essential premise is far-fetched; but I was okay with suspending disbelief that far. (Whether or not black ops organizations would hire a single mom with kids is a matter of speculation, since real life organizations like this don’t publicize their personnel policies. :-) ) But even within the premise Brown creates, much of her plotting simply doesn’t stand examination. Some of the major actions by the villain(s) are at cross-purposes with some of their other major actions; several events that take place here would involve the police in the story, at a level that couldn’t be ignored, but there’s no indication of that here; Donna’s reasoning for one major decision is weak and unconvincing; and Acme (the company she works for) would be much more actively involved in the decision-making at the end, not passive as it is here. Also, characters could not realistically suddenly just shrug off previously incapacitating wounds (which happens here twice), and there are other significant logical slips that took me out of the story. The author writes prolifically, but she apparently wrote this novel too quickly to take her craftsmanship in plotting seriously, or to put any real thought behind it. (That’s a real shame.) Petra is a teenage Roman slave at around the birth of Christ. She is completely under the thumb of her sadistic master, Clarius, until a strange conjunction of events and a poisonous herb with mystical qualities changes the power dynamic entirely. Both of them, together with her lover, Lucius, attain immortality. But it’s an immortality which requires the two men to drink from Petra annually, or they will degenerate into sub-human monsters. Neither is happy with the arrangement: Clarius is not used to being reliant on anyone, least of all his former property, and Lucius hates the fact Petra agreed to submit to their ex-master, in order to save him. As the centuries stretch into millennia, Petra begins, slowly, to put together a group people who will be capable of defeating Lucius and the immortals he has recruited, allowing her to live in eternal peace with Lucius.

Petra is a teenage Roman slave at around the birth of Christ. She is completely under the thumb of her sadistic master, Clarius, until a strange conjunction of events and a poisonous herb with mystical qualities changes the power dynamic entirely. Both of them, together with her lover, Lucius, attain immortality. But it’s an immortality which requires the two men to drink from Petra annually, or they will degenerate into sub-human monsters. Neither is happy with the arrangement: Clarius is not used to being reliant on anyone, least of all his former property, and Lucius hates the fact Petra agreed to submit to their ex-master, in order to save him. As the centuries stretch into millennia, Petra begins, slowly, to put together a group people who will be capable of defeating Lucius and the immortals he has recruited, allowing her to live in eternal peace with Lucius. “Have you not learned by this time that I am not a weak woman, but a strong one? You have harried me and injured me and wronged me and set tortures for me, but here I stand, unharmed. This day I will have my revenge.”

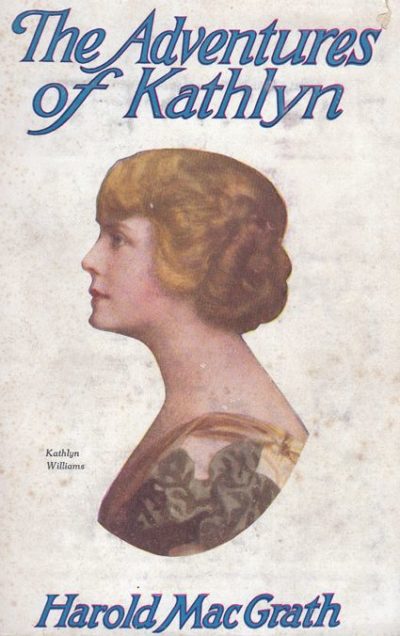

“Have you not learned by this time that I am not a weak woman, but a strong one? You have harried me and injured me and wronged me and set tortures for me, but here I stand, unharmed. This day I will have my revenge.” The writing style, while enthusiastic, is occasionally odd in that it chooses to skip over what should be thrilling moments. I wonder if perhaps this was the book’s way of not stealing the serial’s thunder? For example, as Kaitlyn sets off, accompanying a big cat her father was shipping to its end buyer, a major incident is all but entirely skipped over thus: “How the lion escaped, how the fearless young woman captured it alone, unaided, may be found in the files of all metropolitan newspapers.” Uh, what? But there are times when MacGrath does hit it out of the park, descriptively: “In the blue of night the temple looked as though it had been sculptured out of mist. Here and there the heavy dews, touched by the moon lances, flung back flames of sapphire, cold and sharp.”

The writing style, while enthusiastic, is occasionally odd in that it chooses to skip over what should be thrilling moments. I wonder if perhaps this was the book’s way of not stealing the serial’s thunder? For example, as Kaitlyn sets off, accompanying a big cat her father was shipping to its end buyer, a major incident is all but entirely skipped over thus: “How the lion escaped, how the fearless young woman captured it alone, unaided, may be found in the files of all metropolitan newspapers.” Uh, what? But there are times when MacGrath does hit it out of the park, descriptively: “In the blue of night the temple looked as though it had been sculptured out of mist. Here and there the heavy dews, touched by the moon lances, flung back flames of sapphire, cold and sharp.” The small duchy of Klaar has been impervious to invasion, due to a secure location offering limited access. But when betrayal from within leads to its fall, to the vanguard of an invading Perranese army, heir apparent

The small duchy of Klaar has been impervious to invasion, due to a secure location offering limited access. But when betrayal from within leads to its fall, to the vanguard of an invading Perranese army, heir apparent  It makes sense to treat the second and third volumes in the series as a single entity. Ink Mage worked on its own as a one-off, with a beginning, middle and reasonably well-defined end, and the eight-month pause between installments was not a problem. Duchess and Goddess, however, really need to be read back-to-back. Mage ended with Rina Veraiin having recovered her family’s territory of Klaar, thanks largely to the magical tattoos covering her skin. But the new duchess is discovering that fighting to get territory is one thing, ruling over it on an everyday basis, quite another. Especially since the Perranese invaders repelled in the first volume, are on their way back with a vengeance. For their Empress Mee Hra’Lito needs a big win to keep control of things on her side of the ocean.

It makes sense to treat the second and third volumes in the series as a single entity. Ink Mage worked on its own as a one-off, with a beginning, middle and reasonably well-defined end, and the eight-month pause between installments was not a problem. Duchess and Goddess, however, really need to be read back-to-back. Mage ended with Rina Veraiin having recovered her family’s territory of Klaar, thanks largely to the magical tattoos covering her skin. But the new duchess is discovering that fighting to get territory is one thing, ruling over it on an everyday basis, quite another. Especially since the Perranese invaders repelled in the first volume, are on their way back with a vengeance. For their Empress Mee Hra’Lito needs a big win to keep control of things on her side of the ocean. Especially in the second volume, poor Rina is largely relegated to a supporting role. The major threat to her is, not deities or monsters, but the arguably more insidious danger of an arranged marriage, necessary for the defense of Klaar. Maurizan becomes the action heroine focus, supported by members of the “Birds of Prey”, ex-prostitutes who have become the castle guard, as well as Talbun. It’s decent, yet almost inevitably, suffers from the bane of trilogies, “second volume syndrome”, lacking both a beginning an an end [I will say, for understandable reasons, explained by the author

Especially in the second volume, poor Rina is largely relegated to a supporting role. The major threat to her is, not deities or monsters, but the arguably more insidious danger of an arranged marriage, necessary for the defense of Klaar. Maurizan becomes the action heroine focus, supported by members of the “Birds of Prey”, ex-prostitutes who have become the castle guard, as well as Talbun. It’s decent, yet almost inevitably, suffers from the bane of trilogies, “second volume syndrome”, lacking both a beginning an an end [I will say, for understandable reasons, explained by the author  A largely uninteresting and occasionally tedious read, this begins when the 17-year-old Lizzy Gardner is abducted by a serial killer known as “Spiderman”, for his habit of using insects to terrorize his victims. Lizzy manages to escape, but Spiderman isn’t captured, until almost a decade and a half later, when someone confesses to the crimes. By then, Lizzy has become a private eye, and also giving lectures to young girls, on how to avoid falling victim as she did. She’s not convinced the right person has been caught, and she’s right: the real Spiderman is by no means happy that someone else has taken “credit” for his crimes. So he starts up again, with the eventual aim of recapturing Lizzy, the one who got away…

A largely uninteresting and occasionally tedious read, this begins when the 17-year-old Lizzy Gardner is abducted by a serial killer known as “Spiderman”, for his habit of using insects to terrorize his victims. Lizzy manages to escape, but Spiderman isn’t captured, until almost a decade and a half later, when someone confesses to the crimes. By then, Lizzy has become a private eye, and also giving lectures to young girls, on how to avoid falling victim as she did. She’s not convinced the right person has been caught, and she’s right: the real Spiderman is by no means happy that someone else has taken “credit” for his crimes. So he starts up again, with the eventual aim of recapturing Lizzy, the one who got away… Although I didn’t set out to, in roughly the past year, I’ve read no less than three novels, and one short e-story, that feature female cops as protagonists: this one, “The Academy” (the short e-story that’s the teaser for Robert Dugoni’s Tracy Crosswhite series), Tami Hoag’s A Thin Dark Line, and Justin W. M. Roberts’ The Policewoman. It occurred to me that an instructive way to open this review might be to compare and contrast the four works.

Although I didn’t set out to, in roughly the past year, I’ve read no less than three novels, and one short e-story, that feature female cops as protagonists: this one, “The Academy” (the short e-story that’s the teaser for Robert Dugoni’s Tracy Crosswhite series), Tami Hoag’s A Thin Dark Line, and Justin W. M. Roberts’ The Policewoman. It occurred to me that an instructive way to open this review might be to compare and contrast the four works.