First-time author Lance Charnes and I are Goodreads friends; but I bought my copy of this book, rather than getting it as a gift, and my rating wasn’t influenced by the friendship –it was earned, and would have been even if I’d never heard of the author before reading it. This is an exceptionally assured, polished, powerful and insightful work of fiction; at least one other reviewer has stated that it’s hard to believe this is a first novel, and I have to concur.

First-time author Lance Charnes and I are Goodreads friends; but I bought my copy of this book, rather than getting it as a gift, and my rating wasn’t influenced by the friendship –it was earned, and would have been even if I’d never heard of the author before reading it. This is an exceptionally assured, polished, powerful and insightful work of fiction; at least one other reviewer has stated that it’s hard to believe this is a first novel, and I have to concur.

A former Air Force intelligence officer with training in terrorism incident response, Charnes sets his plot against the background of the real-life polarized and violent international conflicts in the Middle East. As our story opens, a hit squad working for Mossad, Israel’s intelligence agency, has just recently assassinated a high Hezbollah official (along with an unfortunate prostitute whom they just regard as insignificant collateral damage) in Doha, Qatar. They made it look like a drug overdose, but their hand in the matter has been detected, and the IDs they used identified. But these IDs weren’t their own; they stole them from twelve Jews living in Europe and the U.S. The Hezbollah higher-ups know these people to be innocent –but for their own twisted reasons, send out a hit squad of their own to murder them anyway. (And if that fails, there’s a back-up plan: suicide bombings designed to kill hundreds or thousands.) Our hero and heroine here, Brooklyn bookstore manager Jake and Philadelphia legal secretary Miriam, are two people on the hit list. Luckily for them, they’re also both former members of the Israeli military, with the kind of training that’s apt to come in handy here. (And it doesn’t hurt that Jake’s uncle is an inspector in the NYPD.)

A fair amount of action adventure fiction is open to the charge of having rather shallow characters, and often a simplistic world-view that eschews any kind of ethical complexity in favor of a mindless “us against them” fantasy. Those charges, however, won’t stick here. All the important characters here –“guilty” or “innocent,” Jewish or Moslem, Mossad or Hezbollah– are rounded, three-dimensional, and come across as people, not as cartoons. Yes, some may be sympathetic and some may be villains (and not all of either are on one side!); but we can see that the heroes have flaws, and understand what makes the villains tick.

To be sure, our protagonists don’t deserve to die, and our antagonists here are trying to kill them; so yes, that’s a basic line in the sand that shapes our sympathies. And the author doesn’t deliver an analysis of the whole complex Middle East situation, with a breakdown of the grievances of each side. But within the framework of the storyline, it’s made clear that both the Israeli government and its Arab adversaries have innocent blood on their hands, that individuals of both groups are prey to the temptation to dehumanize the other so they can justify anything they want to do them, and that neither hit squad’s superiors are playing by genuinely ethical rules. As we go along, we’re brought face-to-face with ethical conundrums that may not have easy answers.

If you believe you’re morally justified in fighting great injustice, and you want to do it by ethical means that spare the innocent, what exactly DO you do when you’re stuck with co-belligerents who have no such scruples? Do the ends ever justify the means? What balance do you –should you– strike between the claims of blood vengeance and the recognition that hate can hurt you more than it does the hated? Does torture become morally okay if it’s intended to get information that saves an innocent? (And will it really deliver the results we assume it will? Is lying in a police cover-up acceptable if it spares good people from unjust punishment? Is suicide ever the right thing to do? Charnes doesn’t preach, or suggest answers; he just makes readers grapple with the questions. And in the best tradition of Western literature, characters on both sides here also have to grapple with ethical questions –and may come up with answers that they didn’t expect, and that force them to grow or make sacrifices. As action-adventure fans know, this genre at its best is concerned with these kinds of questions as much as any other type of literature is; and the extreme stakes involved give the questions more force and immediacy than they may have in some other genres!

Charnes’ background shows in his obvious knowledge of intelligence procedures, weaponry, and terrorist tactics. This is an exceptionally realistic novel, and an extremely gripping one. Short chapters, each headed by location and date/time, succeed each other rapidly in setting a quick, driving pace (if I’d had unlimited time to read, I could have finished this a lot quicker than I did, because I’d have read almost non-stop!), and the author’s skill in shifting viewpoints from Character(s) A in place X to Character(s) B in place Y –often at a cliff-hanger moment!– ratchets suspense up to nail-biting intensity in places, especially near the end. Good use is made of New York City and Philadelphia geography, by a writer who’s clearly familiar with both locations.

Action scenes are done very well, and both male and female characters are full participants as equals in that area. Of special interest to fans of this site, we have not one but two formidable action ladies; both Miriam and Mossad agent Kelila are tough, gun-packing women, well trained in the techniques of lethal force and without any qualms about using it. (Readers can safely assume that their training is apt to be put to use!) The body count is high; we have a lot of violence here. It isn’t gratuitous, and we don’t have to wallow through excessive gory description; but not everybody who dies has it coming, and this can include developed characters you’ve come to like and care about. In places, this can be painful.

I have a few minor quibbles with character’s actions at times, as not being as smart as I’d expect from them; but these didn’t bother me much overall. This was a quality read from the get-go, and if it had been published by Big Publishing, I believe it would have been a best seller! Hopefully, even in today’s glutted market stacked against independent authors, more and more readers will recognize it for the gem it is. For my part, I’m greatly looking forward to reading the author’s second novel, South.

Note: There’s no explicit sex here, and only one instance of implied premarital (but not casual) sex. A fair amount of bad language (including the f-word in several places) is used by some characters, for the most part in high-stress situations. My impression is that the author employs it for purposes of realism, not for shock value.

Author: Lance Charnes

Publisher: Self-published, available through Amazon, both for Kindle and as a printed book.

A version of this review previously appeared on Goodreads.

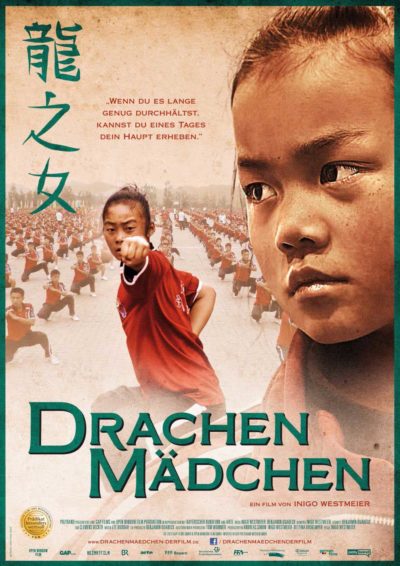

If you’re familiar with Jackie Chan’s life story, you’ll know he (along with fellow future start Sammo Hung and Yuen Biao) was basically brought up in a Peking Opera school, where he learned martial arts and acrobatics as well as theatrical skills. Discipline there was notoriously strict – the film Painted Faces gives a good idea of what it was like. But that was the sixties. Surely no such abusive educational regime exists nowadays?

If you’re familiar with Jackie Chan’s life story, you’ll know he (along with fellow future start Sammo Hung and Yuen Biao) was basically brought up in a Peking Opera school, where he learned martial arts and acrobatics as well as theatrical skills. Discipline there was notoriously strict – the film Painted Faces gives a good idea of what it was like. But that was the sixties. Surely no such abusive educational regime exists nowadays?

Although it’s self-contained enough to be read as a stand-alone, this is actually the sixth novel in Coldsmith’s popular Spanish Bit Saga, a multi-generational epic of the history of the Plains Indians after their culture is transformed by the coming of the horse, focusing on a tribe that calls itself (as most of them did) simply “the People.” (It’s a fictional, composite tribe, but probably modeled most closely on the Cheyenne.) In terms of style and literary vision, it has a lot in common with the series opener, Trail of the Spanish Bit, and the numerous other series installments I’ve read. However, it proved to be my favorite (and, I believe, my wife’s as well). Re-reading it, and re-experiencing parts I’d forgotten, was a reminder of how much I liked it the first time, and still do!

Although it’s self-contained enough to be read as a stand-alone, this is actually the sixth novel in Coldsmith’s popular Spanish Bit Saga, a multi-generational epic of the history of the Plains Indians after their culture is transformed by the coming of the horse, focusing on a tribe that calls itself (as most of them did) simply “the People.” (It’s a fictional, composite tribe, but probably modeled most closely on the Cheyenne.) In terms of style and literary vision, it has a lot in common with the series opener, Trail of the Spanish Bit, and the numerous other series installments I’ve read. However, it proved to be my favorite (and, I believe, my wife’s as well). Re-reading it, and re-experiencing parts I’d forgotten, was a reminder of how much I liked it the first time, and still do!