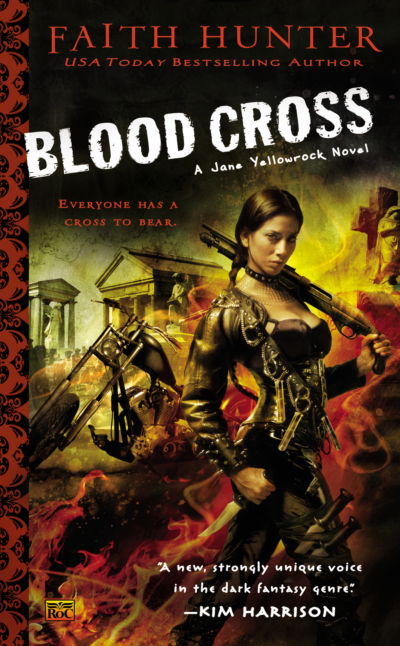

Literary rating: ★★★★

Kick-butt quotient: ☆☆☆

The first book of this series was one of the best supernatural fiction reads, and best action heroine books, that I’ve ever read. It had me fully prepared to continue reading every installment of the series. This second novel picks up just a few days after the end of the first; the denouement of the latter was only the beginning in cleaning up some dark skullduggery afoot in the vampire community of Hunter’s slightly alternate New Orleans. As expected, this one thrust Jane into even more high-risk action and deeper into the mysterious secrets of the Undead race. But even though I gave it just one star less than the previous book, it was ultimately a disappointment, and I won’t keep on reading the series.

The first book of this series was one of the best supernatural fiction reads, and best action heroine books, that I’ve ever read. It had me fully prepared to continue reading every installment of the series. This second novel picks up just a few days after the end of the first; the denouement of the latter was only the beginning in cleaning up some dark skullduggery afoot in the vampire community of Hunter’s slightly alternate New Orleans. As expected, this one thrust Jane into even more high-risk action and deeper into the mysterious secrets of the Undead race. But even though I gave it just one star less than the previous book, it was ultimately a disappointment, and I won’t keep on reading the series.

To be sure, the four stars are earned; this book has many of the same strengths as the previous one. I’d be lying if I said I didn’t really like most of it, and almost to the very end, I fully intended to continue with the series. Hunter’s prose is as compelling and her plotting as strong as ever. The vivid sense of place, and the masterful evocation of the author’s world that draws you in for a complete immersion, is here too. Nor has her genius for characterization, skill at depicting human interactions, and ability to evoke emotional reactions from the reader deserted her. Her deft handling of the vampire mythos, and the exploration of the relationship of Jane and Beast, still fascinates. The serious exploration of Cherokee spirituality is a plus, and I appreciate Hunter’s continued restraint in the use of bad language. As always, she writes action scenes really well; I admire Jane’s prowess as a fighter and willingness to risk her life for things worth fighting for, and I continue to honestly like her as a person. (I did have an issue with the casual drug use of her occasional allies from the projects; in real life, I wouldn’t trust stoned or half-stoned fighters with automatic weapons anywhere near me. But that wasn’t my biggest problem with the book.)

As a person of faith myself, one thing that drew me to the series and to Jane’s character is the fact that she’s depicted as a professing, church-attending Christian. While she wasn’t pictured as a plaster saint (and I wouldn’t expect her, or anybody else in fiction or real life, to be one), the character portrayal in the first book was consistent with who she claimed to be. So nothing prepared me for being blindsided in this book by sexual behavior on Jane’s part (including unmarried sex, engaged in without any moral questioning) that’s totally inconsistent with her claimed Christianity, and which makes her seem, in places, as hormone-driven as the least responsible members of the adolescent community. The sexual content isn’t very explicit; and not in itself anything that would be all that shocking from a secular heroine (such as Modesty Blaise) who doesn’t base her sexual ethics on Christian beliefs, and doesn’t claim to. Coming from one who supposedly does, though, it’s feels like an exercise in false advertising, as if the author wanted to have it both ways to sell more books, with a heroine whose talk can bring in the religious readers and whose actions will appeal to the secular ones. I felt gypped and betrayed by that kind of cynicism, and it leaves a bad taste in the mouth.

Despite my disappointment with that aspect of the novel, it was a thought-provoking read in some ways, raising the question of what it means to be “human.” Because she’s a shapeshifter, Jane is told by one person, and thinks herself, that she isn’t human. But she’s a full-blooded Cherokee (which, if she’s not human, is a contradiction in terms!), and she’s physically, mentally and spiritually just as human as you and I are –she just happens to be differently abled in one respect. In my estimation, that doesn’t make her any more non-human than other people who are differently abled compared to me, like the majority of people who, for instance, can hear tonal differences in music that I can’t, or the small number of people who can guide themselves in the dark by echolocation (and yes, I thought that was strictly fictitious, too, until I learned that it isn’t). Related to this, I’ve often said that I don’t like super-hero stories, because I prefer heroes and heroines with human limitations and vulnerabilities. But I like supernatural yarns about vampires, werewolves, etc. –and the thought struck me, in reading this book, that the difference is less real than one might suppose. In a very real sense, Jane could be called a super-heroine, since she has abilities normal humans don’t. But she’s not SO super-enabled that she’s immortal and above human vulnerability. In the future, I think I might look at super-hero tales with a more nuanced perspective because of that insight!

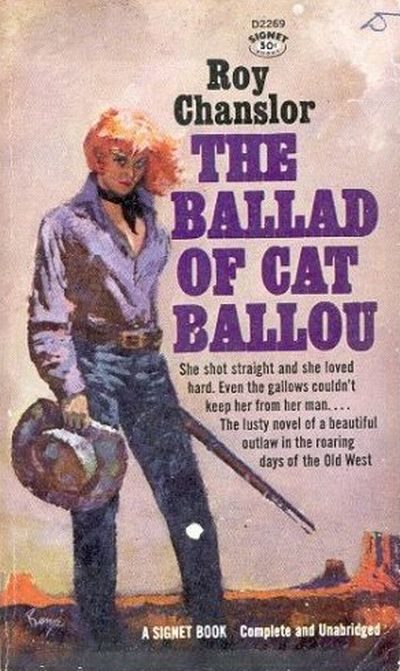

Author: Faith Hunter

Publisher: Roc, available through Amazon, both for Kindle and as a printed book.

A version of this review previously appeared on Goodreads.

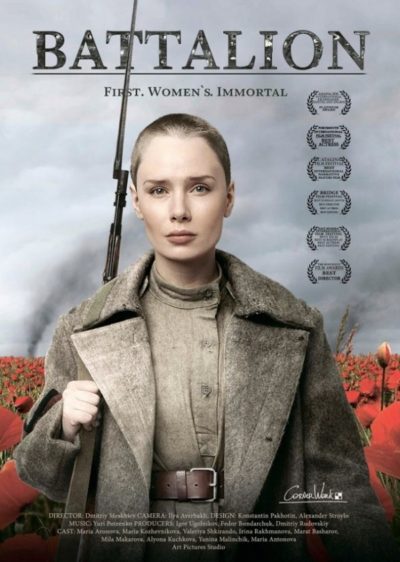

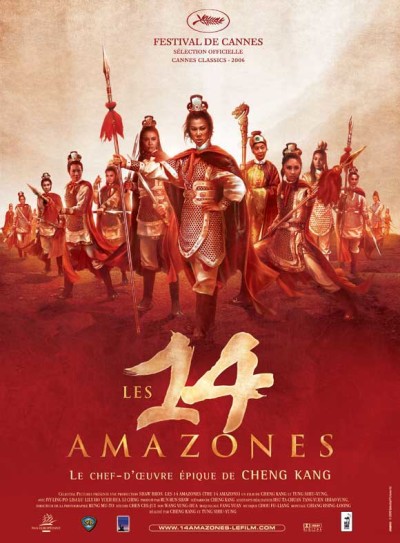

The above is an equal-opportunity truism and, as we see here, applies just as much to the first matriarchal unit in the modern world. This was the charmingly-named 1st Women’s Battalion of Death, created late in World War I, as the Russian Revolution was taking place. Its aim was to encourage the disillusioned regular army into continuing the fight against Germany, in a “If the ladies are fighting, surely you should be, too?” kinda way. At least initially, it’s the story of two sisters, Nadya (Kuchkova) and Vera, daughters of a rich family, who volunteer for the unit after Vera’s fiance, Petya, is killed at the front. Their mother sends their maid, Froska (Rahmanova), to try and protect her daughters, as they go through the training that will turn them into soldiers capable of taking on the enemy. The film climaxes with an initially successful, but ultimately futile, offensive – while the women initially gain ground, the regular army’s morale is so broken, they don’t support the push, allowing the Germans to counterattack [this aspect is largely true to history].

The above is an equal-opportunity truism and, as we see here, applies just as much to the first matriarchal unit in the modern world. This was the charmingly-named 1st Women’s Battalion of Death, created late in World War I, as the Russian Revolution was taking place. Its aim was to encourage the disillusioned regular army into continuing the fight against Germany, in a “If the ladies are fighting, surely you should be, too?” kinda way. At least initially, it’s the story of two sisters, Nadya (Kuchkova) and Vera, daughters of a rich family, who volunteer for the unit after Vera’s fiance, Petya, is killed at the front. Their mother sends their maid, Froska (Rahmanova), to try and protect her daughters, as they go through the training that will turn them into soldiers capable of taking on the enemy. The film climaxes with an initially successful, but ultimately futile, offensive – while the women initially gain ground, the regular army’s morale is so broken, they don’t support the push, allowing the Germans to counterattack [this aspect is largely true to history].