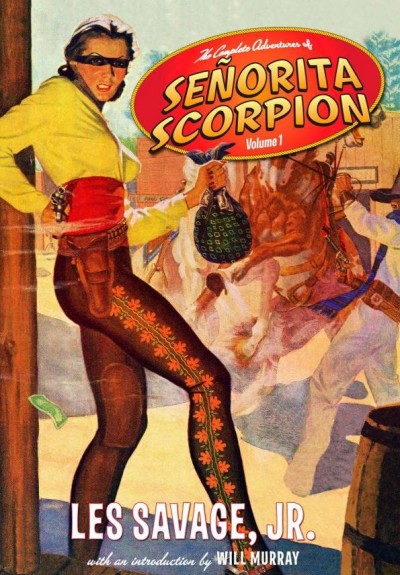

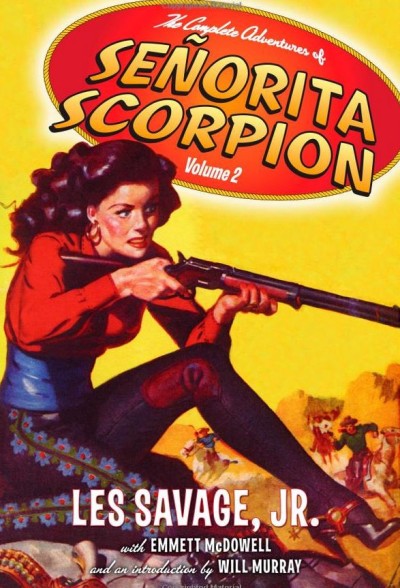

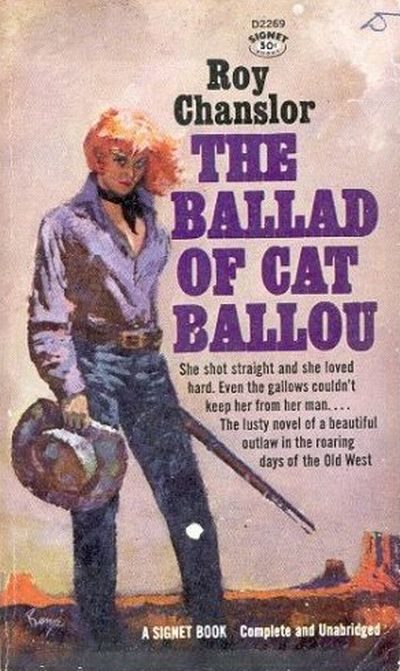

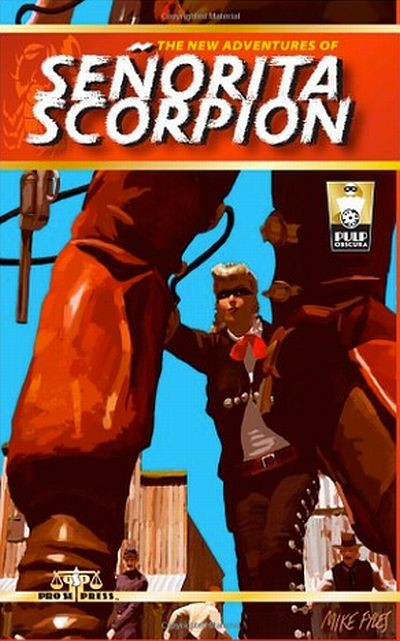

Action adventure fiction, in the pulp era, tended to be a male-dominated field; the writers and readers were overwhelmingly male, and the protagonists having the adventures and engaging in the derring-do tended to be correspondingly male. The culture of that day had deep-rooted stereotypes about the unfitness of the “weaker sex” for strenuous physical challenges, and about the inappropriateness of combat as a role for females who were supposed to be naturally gentle and demure. But there were writings that bucked these assumptions, particularly in the Western genre. Senorita Scorpion, the creation of Les Savage, Jr. (1922-1958), wasn’t actually the first pistol-packing cowgirl to be featured in the Western pulps of the 30s and 40s; but she proved to be the most popular, one of the most unique, and probably the subject of the longest running and thickest corpus of material of any of these fictional ladies: seven stories, originally published in Action Stories from 1944-49. Through its Altus Press imprint, (CreateSpace is just the printing service) Pro Se Press seeks to bring the best fiction of the early modern pulp magazine era back into print, in book form now, for a new generation of fans. These stories (plus one by Emmett McDowell, which used the Senorita Scorpion name for an entirely different character) were a felicitous choice for one of their first projects, in two volumes.

Action adventure fiction, in the pulp era, tended to be a male-dominated field; the writers and readers were overwhelmingly male, and the protagonists having the adventures and engaging in the derring-do tended to be correspondingly male. The culture of that day had deep-rooted stereotypes about the unfitness of the “weaker sex” for strenuous physical challenges, and about the inappropriateness of combat as a role for females who were supposed to be naturally gentle and demure. But there were writings that bucked these assumptions, particularly in the Western genre. Senorita Scorpion, the creation of Les Savage, Jr. (1922-1958), wasn’t actually the first pistol-packing cowgirl to be featured in the Western pulps of the 30s and 40s; but she proved to be the most popular, one of the most unique, and probably the subject of the longest running and thickest corpus of material of any of these fictional ladies: seven stories, originally published in Action Stories from 1944-49. Through its Altus Press imprint, (CreateSpace is just the printing service) Pro Se Press seeks to bring the best fiction of the early modern pulp magazine era back into print, in book form now, for a new generation of fans. These stories (plus one by Emmett McDowell, which used the Senorita Scorpion name for an entirely different character) were a felicitous choice for one of their first projects, in two volumes.

The stories included here are: “Senorita Scorpion” (1944); “The Brand of Senorita Scorpion” (1944); “Secret of Santiago” (1944); “The Curse of Montezuma” (1945); “Brand of the Gallows-Ghost” (1945); “Lash of the Six-Gun Queen” (1947); “Gun Witch of Hoodoo Range” by McDowell (1948); and “The Sting of Senorita Scorpion” (1949). For purposes of this review, the McDowell story is considered separately; the main body of the comments below refer just to the stories by Savage.

Our setting here is Brewster County, Texas in the 1890s. This is a real county, located in the Big Bend area west of the Pecos and north of the Rio Grande, and the geography of the area as depicted by Savage is real, including the inhospitable Dead Horse Mountains. When we first meet protagonist Elgera Douglas, a.k.a. “Senorita Scorpion,” she’s a girl outlaw pulling off a daring robbery, but she’s not an outlaw who wants to prey on others in order to live without working; her motivations are considerably different. They’re rooted in the background of the story series, which is gradually disclosed in the first tale; but it won’t be an undue spoiler to explain it here.

In 1681, a grandee of New Spain, Don Simeon Santiago, discovered a gold mine in the Dead Horse Mountains, originally worked by the local Indians. He built a house and ranch there, in the only valley in the range with enough water to support humans and cattle, and sent several fantastically rich shipments of gold south to Mexico. Soon, however, the ranch was attacked by raiding Comanche, who killed everyone they could find and, when they left, sealed off entrance or egress to the valley by caving in the mine tunnel which served for that purpose. The only survivors were George Douglas, a British-born slave originally captured from an English ship in the Caribbean, and a Mexican Indian slave woman. From these two, over the next two centuries an inbred Douglas clan of mixed Anglo-Indian ancestry and culture grew up in the valley. In 1876, they finally succeeded in digging through the mine and re-uniting with the rest of the world, though they kept the location of their valley secret.

By 1891, clan leader and official landholder John Douglas, Elgera’s father, lies in a coma, and the Santiago lands are under the covetous eye of ruthless cattle baron Anse Hawkman, who owns everything in the area worth owning and has used legal chicanery to force the smaller landholders off their claims. Elgera (“El Gera” is Spanish for “the blonde one”) is one of three children, the only girl, and not the oldest; but with her father disabled she’s the undisputed leader of the family. Savage never actually explains why; we’re left to infer that it’s because of her strong, born-leader personality –which is definitely evidenced– and the respect commanded, in a situation where fighting is a necessity, by her formidable gun skills, which considerably surpass those of most men. She’s become an outlaw, as the law defines it, in order to strike back at Hawkman and his interests.

From this beginning, the first four stories proceed in a chronological arc; each is self contained, but the following ones build on the preceding ones in terms of character and situational development, so that what we have is a genuine story cycle. In the later three stories, the chronological relationship to the rest of the corpus isn’t as clear, except that they all take place after the events of the first story, and that “Lash of the Six-Gun Queen” is set near the end of the decade. Savage makes statements inconsistent in details with what he wrote earlier in one story, and another tale also gives some evidence of forgetfulness on his part. The rest of the Douglas clan simply disappears in the later stories, and their unique sociological circumstances aren’t explored at all, while the Santiago Ranch functions about like a set or a piece of furniture; there’s not much attention to its fortunes or the practicalities of running it. Elgera’s supposedly well-known skill at cards is only brought out in “Brand of the Gallows-Ghost,” and never mentioned elsewhere.

From this beginning, the first four stories proceed in a chronological arc; each is self contained, but the following ones build on the preceding ones in terms of character and situational development, so that what we have is a genuine story cycle. In the later three stories, the chronological relationship to the rest of the corpus isn’t as clear, except that they all take place after the events of the first story, and that “Lash of the Six-Gun Queen” is set near the end of the decade. Savage makes statements inconsistent in details with what he wrote earlier in one story, and another tale also gives some evidence of forgetfulness on his part. The rest of the Douglas clan simply disappears in the later stories, and their unique sociological circumstances aren’t explored at all, while the Santiago Ranch functions about like a set or a piece of furniture; there’s not much attention to its fortunes or the practicalities of running it. Elgera’s supposedly well-known skill at cards is only brought out in “Brand of the Gallows-Ghost,” and never mentioned elsewhere.

The major characters are well-developed, and several appear in more than one of the stories. (Chisos Owens tends to play as large a role in most of the stories as Elgera does, and actually does more of the fighting.) Savage develops his plots with considerable originality and artistry, and the stories benefit from his trademark serious research to ground his work in actual Western history. (The fraudulent so-called “History of Montezuma,” for instance, really was produced in 1846 under the conditions he describes in “The Curse of Montezuma;” and while I haven’t been able to check his details about 17th-century Native American and Spanish mining/smelting practices in “Secret of Santiago,” they have a ring of truth.) He writes action scenes well; he’s an excellent prose stylist, and has a good sense of pacing, and the stories employ elements of mystery which are very effective in adding to the suspense he conjures. Elgera’s a likable character, as are the various good guys who assist her; and the villains are the sort you love to root against. A half-Indian heroine is as much of a trail-blazing feature, in this period, as a combat-capable one, and Savage’s treatment of Hispanic and Indian characters isn’t racist; some are villains, but others are treated very positively.

Critics might complain that some plot elements are a bit exotic (such as a character who’s a Satanist, or the premise of a peyote-based cult in one story), or that there’s some reliance on coincidence in places. But peyote use really is historically a feature of Southwestern Indian religion, and coincidence IS at times a feature of real life, too. There’s not much bad language in the stories (McDowell uses more of it than Savage does), and what there is isn’t particularly rough.

In terms of her action chops, we’re told much more often about Elgera’s gun skills than we’re shown them –but we are shown them occasionally. She uses lethal force sparingly (and only in defense of herself or others), though when she has to, she takes it calmly in stride. (Bad guys who take her on hand to hand –and she’s no slouch at that type of fighting, either!– usually wind up killing themselves accidentally; but as a group, they’re too stupid to recognize that pattern and avoid it. :-) )

Will Murray contributes introductions to both volumes; the second one deals mostly with the genesis and publication of the stories, but the first one regrettably concentrates mostly on the sex appeal of the pulp cowgirl characters in general and the more salacious aspects of the cover art. To be sure, many males then and now were, and are, culturally conditioned to view both real and fictional women only, or primarily, as sexual commodities. But that’s not, IMO, the most helpful lens here for viewing the character –nor the primary one that Savage invites us to use. Yes, he depicts Elgera as powerfully attractive to most of his male characters (and she tends to be fickle in her own romantic attractions –one of my primary quibbles with his portrayal of the character). But the stories certainly aren’t about sex, Elgera and her male admirers never do anything more than kiss, and her sexuality is just an ancillary part –not the be-all-and-end-all– of who her character is.

A brief word will suffice about McDowell’s story. My wife considered it out of place, and a detriment to the book; it’s included because Savage’s publishers, when he was too busy working on a novel at the time, enlisted McDowell to write a Senorita Scorpion story, and this is what they got. He used the name, but makes the woman’s character and circumstances totally different from Savage’s Elgera, and changes the setting to Arizona in the early 1880s to boot. Essentially, it’s a story about a completely different woman with the same nickname. Taken on its own terms, though, it’s actually a solid story with an excellent twist, and one of my favorites in the book.

Author: Les Savage, Jr.

Publisher: Altus Press, available through Amazon, both for Kindle and as printed books: Volume 1 and Volume 2

A version of this review previously appeared on Goodreads.

This fourth installment of the Jade del Cameron series has much the same strengths and general style of the previous books. We find Jade back in British East Africa, a few months after the events of the third book, The Serpent’s Daughter, and again encounter our old friends from the first two books. She’s supplementing her writing income by using her lariat and photography skills to help Perkins and Daley, the two partners in a small company that secures African animals for U.S. zoos. But we sense early on that her sleuthing skills may also be called on again, with the discovery of the dead body of a merchant from Nairobi (1920 population, ca. 11,000 –white population, ca. 3,000). Is his death, as the authorities initially suppose, suicide –or murder? And where is his unhappy wife? And did she or didn’t she have a recent unreported, unattended childbirth? Inquiring minds want to know; and Jade has an inquiring mind, soon made more so by the fact that the lead investigator seems to consider her beau, Sam Featherstone, a prime suspect.

This fourth installment of the Jade del Cameron series has much the same strengths and general style of the previous books. We find Jade back in British East Africa, a few months after the events of the third book, The Serpent’s Daughter, and again encounter our old friends from the first two books. She’s supplementing her writing income by using her lariat and photography skills to help Perkins and Daley, the two partners in a small company that secures African animals for U.S. zoos. But we sense early on that her sleuthing skills may also be called on again, with the discovery of the dead body of a merchant from Nairobi (1920 population, ca. 11,000 –white population, ca. 3,000). Is his death, as the authorities initially suppose, suicide –or murder? And where is his unhappy wife? And did she or didn’t she have a recent unreported, unattended childbirth? Inquiring minds want to know; and Jade has an inquiring mind, soon made more so by the fact that the lead investigator seems to consider her beau, Sam Featherstone, a prime suspect.

Action adventure fiction, in the pulp era, tended to be a male-dominated field; the writers and readers were overwhelmingly male, and the protagonists having the adventures and engaging in the derring-do tended to be correspondingly male. The culture of that day had deep-rooted stereotypes about the unfitness of the “weaker sex” for strenuous physical challenges, and about the inappropriateness of combat as a role for females who were supposed to be naturally gentle and demure. But there were writings that bucked these assumptions, particularly in the Western genre. Senorita Scorpion, the creation of Les Savage, Jr. (1922-1958), wasn’t actually the first pistol-packing cowgirl to be featured in the Western pulps of the 30s and 40s; but she proved to be the most popular, one of the most unique, and probably the subject of the longest running and thickest corpus of material of any of these fictional ladies: seven stories, originally published in Action Stories from 1944-49. Through its Altus Press imprint, (CreateSpace is just the printing service) Pro Se Press seeks to bring the best fiction of the early modern pulp magazine era back into print, in book form now, for a new generation of fans. These stories (plus one by Emmett McDowell, which used the Senorita Scorpion name for an entirely different character) were a felicitous choice for one of their first projects, in two volumes.

Action adventure fiction, in the pulp era, tended to be a male-dominated field; the writers and readers were overwhelmingly male, and the protagonists having the adventures and engaging in the derring-do tended to be correspondingly male. The culture of that day had deep-rooted stereotypes about the unfitness of the “weaker sex” for strenuous physical challenges, and about the inappropriateness of combat as a role for females who were supposed to be naturally gentle and demure. But there were writings that bucked these assumptions, particularly in the Western genre. Senorita Scorpion, the creation of Les Savage, Jr. (1922-1958), wasn’t actually the first pistol-packing cowgirl to be featured in the Western pulps of the 30s and 40s; but she proved to be the most popular, one of the most unique, and probably the subject of the longest running and thickest corpus of material of any of these fictional ladies: seven stories, originally published in Action Stories from 1944-49. Through its Altus Press imprint, (CreateSpace is just the printing service) Pro Se Press seeks to bring the best fiction of the early modern pulp magazine era back into print, in book form now, for a new generation of fans. These stories (plus one by Emmett McDowell, which used the Senorita Scorpion name for an entirely different character) were a felicitous choice for one of their first projects, in two volumes. From this beginning, the first four stories proceed in a chronological arc; each is self contained, but the following ones build on the preceding ones in terms of character and situational development, so that what we have is a genuine story cycle. In the later three stories, the chronological relationship to the rest of the corpus isn’t as clear, except that they all take place after the events of the first story, and that “Lash of the Six-Gun Queen” is set near the end of the decade. Savage makes statements inconsistent in details with what he wrote earlier in one story, and another tale also gives some evidence of forgetfulness on his part. The rest of the Douglas clan simply disappears in the later stories, and their unique sociological circumstances aren’t explored at all, while the Santiago Ranch functions about like a set or a piece of furniture; there’s not much attention to its fortunes or the practicalities of running it. Elgera’s supposedly well-known skill at cards is only brought out in “Brand of the Gallows-Ghost,” and never mentioned elsewhere.

From this beginning, the first four stories proceed in a chronological arc; each is self contained, but the following ones build on the preceding ones in terms of character and situational development, so that what we have is a genuine story cycle. In the later three stories, the chronological relationship to the rest of the corpus isn’t as clear, except that they all take place after the events of the first story, and that “Lash of the Six-Gun Queen” is set near the end of the decade. Savage makes statements inconsistent in details with what he wrote earlier in one story, and another tale also gives some evidence of forgetfulness on his part. The rest of the Douglas clan simply disappears in the later stories, and their unique sociological circumstances aren’t explored at all, while the Santiago Ranch functions about like a set or a piece of furniture; there’s not much attention to its fortunes or the practicalities of running it. Elgera’s supposedly well-known skill at cards is only brought out in “Brand of the Gallows-Ghost,” and never mentioned elsewhere. Full disclosure up front: the author and I are in a couple of Goodreads groups together, so I was aware of his debut novel; and I knew he’d offered a free review e-copy to group members. I didn’t request one, since I prefer to read in print format; but on the recommendation of my friend David Wittlinger, I did put my name in for the paperback Goodreads giveaway (which is still ongoing!). When Bran became aware of my preference for paper, he kindly gifted me with a paperback copy, which I really appreciate. His openness to honest feedback is also appreciated; he made it clear from the outset that he’d appreciate even a bad review as long as it was honest and provided him with feedback. It didn’t take me long to read enough to tell that my review wasn’t going to be a bad one!

Full disclosure up front: the author and I are in a couple of Goodreads groups together, so I was aware of his debut novel; and I knew he’d offered a free review e-copy to group members. I didn’t request one, since I prefer to read in print format; but on the recommendation of my friend David Wittlinger, I did put my name in for the paperback Goodreads giveaway (which is still ongoing!). When Bran became aware of my preference for paper, he kindly gifted me with a paperback copy, which I really appreciate. His openness to honest feedback is also appreciated; he made it clear from the outset that he’d appreciate even a bad review as long as it was honest and provided him with feedback. It didn’t take me long to read enough to tell that my review wasn’t going to be a bad one!