★★★

★★★

“Drawn that way.”

1995 possibly marked a recent low for the commercial appeal of action heroines in Hollywood. December would give us one of the biggest disaster movies of all time, in Cutthroat Island and March saw Tank Girl bomb. Together with this attempt to give the Western a female spin, the three movies had a combined budget of $155 million, but grossed less than $33 million. While Westerns were enjoying a return to popularity in the years after Unforgiven, it was almost as if Sony had learned nothing from Fox’s dud in the same area the previous year, Bad Girls. They instead doubled down on something which was not just a Western, but specifically a pastiche of the spaghetti Western subgenre.

In hindsight, its commercial failure was almost inevitable, even though after Basic Instinct in 1992, Sharon Stone was one of Hollywood’s hottest actresses. So when Sony bought Simon Moore’s script the following year, they approached her to star. She not only came on board as the lead actress, she also became one of the film’s producers, and had no hesitation in wielding that power. For example, she insisted that Sam Raimi – then, largely known only for his work on the Evil Dead trilogy – had to direct it, or she would not be involved. Similarly, she went to bat for then largely unknown actors Russell Crowe and Leonardo DiCaprio, going so far as to pay the latter’s salary herself. The subsequent Oscars for both men suggest she had a good eye for upcoming thespians.

Moore was eventually fired, with the studio bringing John Sayles on board. However, Moore was re-hired three weeks before shooting was scheduled to start, due to the movie becoming excessively long: he simply discarded all of Sayles’s changes, and Sony accepted what was basically the original version. However, during shooting, Raimi realized he had an issue. “I came to the studio and said, can you find me a writer? I’ve shot this movie, and the end isn’t quite working… They suggested Joss Whedon, who was doing Buffy, so I met Joss and he saw the movie, and he helped me solve this ending in one afternoon,” adding one more name to the list of future stars who worked on the film.

Moore was eventually fired, with the studio bringing John Sayles on board. However, Moore was re-hired three weeks before shooting was scheduled to start, due to the movie becoming excessively long: he simply discarded all of Sayles’s changes, and Sony accepted what was basically the original version. However, during shooting, Raimi realized he had an issue. “I came to the studio and said, can you find me a writer? I’ve shot this movie, and the end isn’t quite working… They suggested Joss Whedon, who was doing Buffy, so I met Joss and he saw the movie, and he helped me solve this ending in one afternoon,” adding one more name to the list of future stars who worked on the film.

The concept here is pure gimmick. The town of Redemption lives under the iron hand of Herod (Hackman), who organizes an annual gunfight contest he always wins, partly to flush out anyone who might be plotting against him, mostly because he enjoys it. This time, 15 other entrants are drawn by the $100,000 prize, as well as other reasons. The more or less willing participants include Herod’s son (DiCaprio), former partner Cort (Crowe) and a mysterious woman (Stone), named in the credits as The Lady, actually called Ellen. She has a particular grudge against Herod, since his involvement in the death of her father, though things are more complex than you initially suspect. Getting revenge, however, requires Ellen to get through a tournament increasingly stacked against her.

The Variety review at the time nails the main problem: “Given the inevitability of an Ellen-Herod showdown, despite a couple of twists [Moore] has thrown into the last reel, the film quickly becomes hamstrung by the rigid dramatic constraints imposed upon it by the gun tournament format. No matter how many fancy ways Raimi invents to stage the shootouts, the tedium is quick in coming, and there’s nothing else going on between times to build up suspense, character or interest.” Moore has failed to grasp that while Westerns often climaxed in a gunfight, this does not mean that more gunfights = a better film. They are the full-stop at the end of a cinematic sentence. And like. Those, when. You use them. Too often, the. Results are jarring rather. Than effective.

It’s a shame, because the supporting cast is quite stellar, and deserve better. Outside of those already mentioned, there’s also Tobin Bell, who’d go on to become horror icon Jigsaw in the Saw franchise; Lance Henriksen; Keith David; and, although his scenes were deleted, Raimi’s long-time friend, Bruce Campbell. Seeing the talent which gets rushed in and out of the story in about five minutes makes me wonder if a feature film was the best medium for the idea. It might have worked better as an ongoing television series, each episode telling the back story of the participants and ending in their duel. A rotating series of guest stars would have worked very nicely, with the season covering one of Herod’s contests, leading up to the final gunfight in the last installment.

It’s a shame, because the supporting cast is quite stellar, and deserve better. Outside of those already mentioned, there’s also Tobin Bell, who’d go on to become horror icon Jigsaw in the Saw franchise; Lance Henriksen; Keith David; and, although his scenes were deleted, Raimi’s long-time friend, Bruce Campbell. Seeing the talent which gets rushed in and out of the story in about five minutes makes me wonder if a feature film was the best medium for the idea. It might have worked better as an ongoing television series, each episode telling the back story of the participants and ending in their duel. A rotating series of guest stars would have worked very nicely, with the season covering one of Herod’s contests, leading up to the final gunfight in the last installment.

I’m not certain Stone is perhaps the best candidate for the role, since she seems to think staring really hard is the key to dramatic success. You’d think she might have known better, given apparent action heroine ambitions from relatively early in her career. Even before breaking through to stardom in Total Recall, she was in her fair share of adventure flicks – albeit not very successful ones – such as King Solomon’s Mines and Allan Quatermain and the Lost City of Gold. Unlike Geena Davis, however, Stone didn’t seem to persist in her efforts: the critical acclaim she received the same year for Casino, pushed her career back toward more dramatic pastures. This therefore stands out as something of an oddity in her filmography.

Time has perhaps been slightly kinder to this than its companions in action heroine failure for the year. Raimi eventually showed an ability to deliver this kind of comic-book spectacle with his work on the Spiderman franchise, and that may have been a better home for his stylistically excess flourishes than this. Naturally, as an Arizona resident, this film now triggers a certain amount of native pride, having been filmed largely around the state, in particular at Old Tucson Studios [unfortunately, a good portion of which burned down a couple of months after Quick was released, forcing its closure for two years] and Mescal, 40 miles southeast of Tucson.

It may not be the greatest Western – or even a particularly good Western. Yet two decades later, it likely remains the biggest production in the genre with a female lead, and as such, it deserves a certain respect. Especially when the commercial failures in recent years of Jane Got a Gun and Woman Walks Ahead, suggest that position at the head of the class probably isn’t going to be under threat, any time soon.

Dir: Sam Raimi

Star: Sharon Stone, Gene Hackman, Russell Crowe, Leonardo DiCaprio

Josephine “Joe” Cassidy (Eiland) is promised in marriage to Tom (Jenkins), the son of the area’s richest rancher, but her heart actually belongs to Jakob (Grasl), the Indian who is Tom’s adopted brother. The two lovers consummate their relationship when Tom is away, but the spurned fiancee hatches a long-term plan to get revenge. Years later, after becoming the local sheriff, he uses these connections to frame and execute Jakob for murder. Word of this reaches Joe, who conveniently for the plot is handy with a firearm, because her father (Cramer) was a renowned bounty-hunter, and passed on the necessary skills to her. Dying her hair red – hence the title – she sets out to take revenge on Tom, only for him to reveal that Jakob is not dead… Not yet, anyway.

Josephine “Joe” Cassidy (Eiland) is promised in marriage to Tom (Jenkins), the son of the area’s richest rancher, but her heart actually belongs to Jakob (Grasl), the Indian who is Tom’s adopted brother. The two lovers consummate their relationship when Tom is away, but the spurned fiancee hatches a long-term plan to get revenge. Years later, after becoming the local sheriff, he uses these connections to frame and execute Jakob for murder. Word of this reaches Joe, who conveniently for the plot is handy with a firearm, because her father (Cramer) was a renowned bounty-hunter, and passed on the necessary skills to her. Dying her hair red – hence the title – she sets out to take revenge on Tom, only for him to reveal that Jakob is not dead… Not yet, anyway.

This Western was released in 1953, and feels decades ahead of its time. It’s set toward the end of the Civil War, in the town of Border City, which sits exactly on the dividing line between North and South. A settlement built on mining, it has remained a neutral zone under strictly enforced rules laid down by Mayor Delilah Courtney, selling lead to both sides for their bullets. As well as Yankee and Confederate soldiers in the area, the picture is complicated by Quantrill’s Raiders, a group of independent (yet generally pro-South) soldiers under Charles Quantrill (Donlevy). [They really existed, and as the film reveals, had some well-known names in their ranks]

This Western was released in 1953, and feels decades ahead of its time. It’s set toward the end of the Civil War, in the town of Border City, which sits exactly on the dividing line between North and South. A settlement built on mining, it has remained a neutral zone under strictly enforced rules laid down by Mayor Delilah Courtney, selling lead to both sides for their bullets. As well as Yankee and Confederate soldiers in the area, the picture is complicated by Quantrill’s Raiders, a group of independent (yet generally pro-South) soldiers under Charles Quantrill (Donlevy). [They really existed, and as the film reveals, had some well-known names in their ranks] ★★★

★★★ Moore was eventually fired, with the studio bringing John Sayles on board. However, Moore was re-hired three weeks before shooting was scheduled to start, due to the movie becoming excessively long: he simply discarded all of Sayles’s changes, and Sony accepted what was basically the original version. However, during shooting, Raimi realized he

Moore was eventually fired, with the studio bringing John Sayles on board. However, Moore was re-hired three weeks before shooting was scheduled to start, due to the movie becoming excessively long: he simply discarded all of Sayles’s changes, and Sony accepted what was basically the original version. However, during shooting, Raimi realized he  It’s a shame, because the supporting cast is quite stellar, and deserve better. Outside of those already mentioned, there’s also Tobin Bell, who’d go on to become horror icon Jigsaw in the Saw franchise; Lance Henriksen; Keith David; and, although his scenes were deleted, Raimi’s long-time friend, Bruce Campbell. Seeing the talent which gets rushed in and out of the story in about five minutes makes me wonder if a feature film was the best medium for the idea. It might have worked better as an ongoing television series, each episode telling the back story of the participants and ending in their duel. A rotating series of guest stars would have worked very nicely, with the season covering one of Herod’s contests, leading up to the final gunfight in the last installment.

It’s a shame, because the supporting cast is quite stellar, and deserve better. Outside of those already mentioned, there’s also Tobin Bell, who’d go on to become horror icon Jigsaw in the Saw franchise; Lance Henriksen; Keith David; and, although his scenes were deleted, Raimi’s long-time friend, Bruce Campbell. Seeing the talent which gets rushed in and out of the story in about five minutes makes me wonder if a feature film was the best medium for the idea. It might have worked better as an ongoing television series, each episode telling the back story of the participants and ending in their duel. A rotating series of guest stars would have worked very nicely, with the season covering one of Herod’s contests, leading up to the final gunfight in the last installment.

Despite the male-oriented title, there’s no doubt who the star is: Vienna (Crawford), a former saloon girl who has clawed her way up to owning her own place, on the outskirts of an Arizona mining town. She has inside knowledge of the route the railroad is going to take, and chose her location with that in mind. But there’s stiff local opposition, from those who don’t want the railroad, or who object to her allowing the Dancing Kid (Brady) and his gang, suspects in a stagecoach robbery, to frequent her establishment. Leading those with a dim view of Vienna, is Emma Small (McCambridge), whose brother was killed in the robbery.

Despite the male-oriented title, there’s no doubt who the star is: Vienna (Crawford), a former saloon girl who has clawed her way up to owning her own place, on the outskirts of an Arizona mining town. She has inside knowledge of the route the railroad is going to take, and chose her location with that in mind. But there’s stiff local opposition, from those who don’t want the railroad, or who object to her allowing the Dancing Kid (Brady) and his gang, suspects in a stagecoach robbery, to frequent her establishment. Leading those with a dim view of Vienna, is Emma Small (McCambridge), whose brother was killed in the robbery.

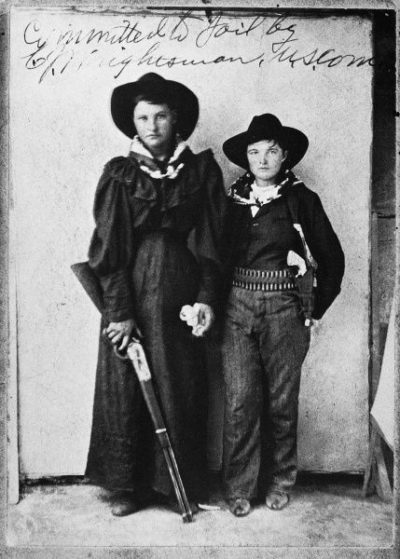

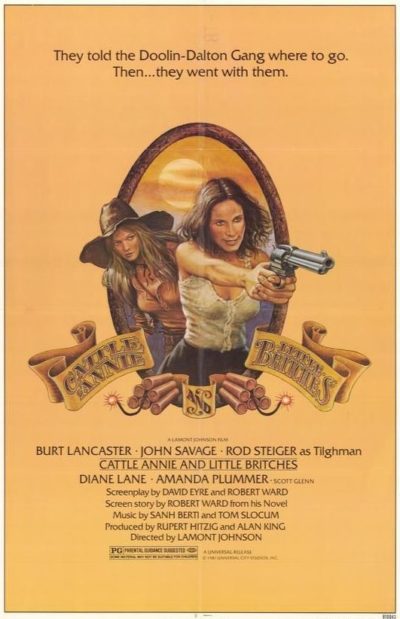

There’s something satisfyingly circular about the story of Cattle Annie and Little Britches. Two teenage girls, inspired by the questionably accurate literary exploits of Western outlaw derring-do, leave their homes and families to join those outlaws. They end up becoming the stuff of these same legends themselves, with their story being turned into a Hollywood movie (see below). Art imitating life imitating art. Given this, discovering the truth behind the myth is almost impossible, with sources telling different versions, and often contradicting each other. As such, take what follows as a best guess…

There’s something satisfyingly circular about the story of Cattle Annie and Little Britches. Two teenage girls, inspired by the questionably accurate literary exploits of Western outlaw derring-do, leave their homes and families to join those outlaws. They end up becoming the stuff of these same legends themselves, with their story being turned into a Hollywood movie (see below). Art imitating life imitating art. Given this, discovering the truth behind the myth is almost impossible, with sources telling different versions, and often contradicting each other. As such, take what follows as a best guess…

For example, rather than being born and brought up in Oklahoma, the duo are portrayed as making their way out to California to seek their fortune, when they’re forcibly detoured to Guthrie, OK, There, they encounter Bill Doolin (Lancaster) when he and his gang visit the town. Annie falls for gang member Bittercreek Newcomb (John Savage) and they end up being taken by him to the gang’s hideout. Their knowledge of the Doolin Gang is entirely based on the embellished stories they’ve heard about them, and they’re disappointing to find reality comes up short.

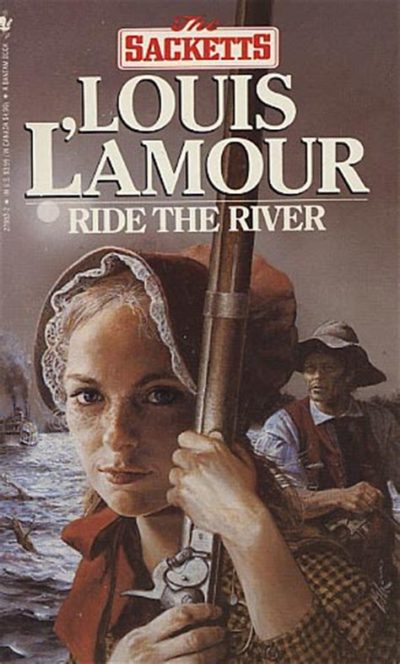

For example, rather than being born and brought up in Oklahoma, the duo are portrayed as making their way out to California to seek their fortune, when they’re forcibly detoured to Guthrie, OK, There, they encounter Bill Doolin (Lancaster) when he and his gang visit the town. Annie falls for gang member Bittercreek Newcomb (John Savage) and they end up being taken by him to the gang’s hideout. Their knowledge of the Doolin Gang is entirely based on the embellished stories they’ve heard about them, and they’re disappointing to find reality comes up short. Goodreads characterizes this novel, set in 1840, as the fifth volume in the author’s Sackett series. The fictional Sackett family, in L’Amour’s writings, are descended from tough, larger-than-life Barnabas Sackett, who emigrated to America in the 1600s and settled on the frontier, and who laid down a law for his descendants that whenever a Sackett was in trouble, the rest were bound to lend their aid. This book is indeed about a Sackett, and no doubt chronologically the fifth in that sequence. But the sequence forms a multi-generational saga in which the individual books are generally about different people; though some knowledge of the family origins, as mentioned above, might be helpful (and is repeated in the text of this book, for readers who didn’t read the series opener), they can be read perfectly well as stand-alones. (I haven’t read any of the other Sackett novels.) L’Amour also wrote sequences of novels and stories about two other fictional families that bred adventurous pioneers, the Chantrys and the Talons, whose paths sometimes cross those of the Sacketts –and the paths of a couple of the Chantrys will bring them into this tale as well.

Goodreads characterizes this novel, set in 1840, as the fifth volume in the author’s Sackett series. The fictional Sackett family, in L’Amour’s writings, are descended from tough, larger-than-life Barnabas Sackett, who emigrated to America in the 1600s and settled on the frontier, and who laid down a law for his descendants that whenever a Sackett was in trouble, the rest were bound to lend their aid. This book is indeed about a Sackett, and no doubt chronologically the fifth in that sequence. But the sequence forms a multi-generational saga in which the individual books are generally about different people; though some knowledge of the family origins, as mentioned above, might be helpful (and is repeated in the text of this book, for readers who didn’t read the series opener), they can be read perfectly well as stand-alones. (I haven’t read any of the other Sackett novels.) L’Amour also wrote sequences of novels and stories about two other fictional families that bred adventurous pioneers, the Chantrys and the Talons, whose paths sometimes cross those of the Sacketts –and the paths of a couple of the Chantrys will bring them into this tale as well. You know you’re deep into one-man, to put it mildly, film-making territory, when the same name gets 7½ of the first 10 credits (one is shared). That’s spreading your talents thin, even if you are Steven Spielberg. And Sean LaFollette definitely isn’t Spielberg. The story is told in flashback, with the heroine Elizabeth (Burgess) the proud recipient of two pink-handled revolvers for her birthday. While she’s off getting her gun-belt, the family saloon is invaded by a group of out of town criminals, who take the rest of her family hostage, and shoot her grandfather dead. Fortunately, Elizabeth takes after her late mother, who was a crack-shot, and is therefore in a good position to pick apart the perpetrators.

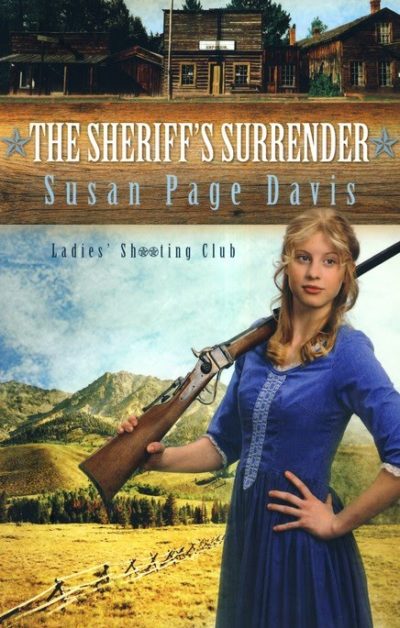

You know you’re deep into one-man, to put it mildly, film-making territory, when the same name gets 7½ of the first 10 credits (one is shared). That’s spreading your talents thin, even if you are Steven Spielberg. And Sean LaFollette definitely isn’t Spielberg. The story is told in flashback, with the heroine Elizabeth (Burgess) the proud recipient of two pink-handled revolvers for her birthday. While she’s off getting her gun-belt, the family saloon is invaded by a group of out of town criminals, who take the rest of her family hostage, and shoot her grandfather dead. Fortunately, Elizabeth takes after her late mother, who was a crack-shot, and is therefore in a good position to pick apart the perpetrators. Having started our acquaintance with the Ladies Shooting Club trilogy last year with the third book, The Blacksmith’s Bravery (long story), my wife Barb and I are now reading the other two volumes in order. Neither of us were disappointed in this one! My reviewing it here was a happy surprise. Although the covers of all three books feature gun-toting women, and a basic plot current of the trilogy is women learning to take responsibility for defending themselves and others, the heroine of the third book wasn’t actually called on to engage in any gun-fighting action. So I assumed the same would be the case here. But [at the risk of a mild “spoiler” –though for fans of this site, this will add interest rather than spoil it :-)], in this series opener, our heroine does need to step up to the plate with a Winchester. (Contrary to many fictional and movie depictions, rifles were used more for serious shooting in the Old West than six-guns). Despite that difference, though, both books have a lot of similarity in tone, content and style. Since I gave the concluding volume five stars on Goodreads, that’s a good thing!

Having started our acquaintance with the Ladies Shooting Club trilogy last year with the third book, The Blacksmith’s Bravery (long story), my wife Barb and I are now reading the other two volumes in order. Neither of us were disappointed in this one! My reviewing it here was a happy surprise. Although the covers of all three books feature gun-toting women, and a basic plot current of the trilogy is women learning to take responsibility for defending themselves and others, the heroine of the third book wasn’t actually called on to engage in any gun-fighting action. So I assumed the same would be the case here. But [at the risk of a mild “spoiler” –though for fans of this site, this will add interest rather than spoil it :-)], in this series opener, our heroine does need to step up to the plate with a Winchester. (Contrary to many fictional and movie depictions, rifles were used more for serious shooting in the Old West than six-guns). Despite that difference, though, both books have a lot of similarity in tone, content and style. Since I gave the concluding volume five stars on Goodreads, that’s a good thing! This workmanlike effort, if not particularly memorable, does at least cross two genres not frequently combined: the Western and the post-apocalypse movie. For it takes place in a world where global warming and other stuff have created a poisoned wasteland. Consequently, the currencies of choice are water purification tablets and silver, the latter being the raw ingredient in the air filtration masks which have become essential. Using vehicles powered by fossil fuels is totally outlawed, and those who do have rewards placed on their heads, attracting the attention of bounty hunters.

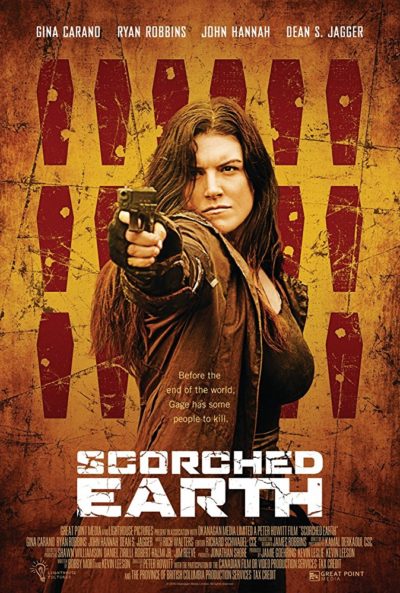

This workmanlike effort, if not particularly memorable, does at least cross two genres not frequently combined: the Western and the post-apocalypse movie. For it takes place in a world where global warming and other stuff have created a poisoned wasteland. Consequently, the currencies of choice are water purification tablets and silver, the latter being the raw ingredient in the air filtration masks which have become essential. Using vehicles powered by fossil fuels is totally outlawed, and those who do have rewards placed on their heads, attracting the attention of bounty hunters.