“This is the West, sir. When the legend becomes fact, print the legend.”

— The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance

The fact

There’s something satisfyingly circular about the story of Cattle Annie and Little Britches. Two teenage girls, inspired by the questionably accurate literary exploits of Western outlaw derring-do, leave their homes and families to join those outlaws. They end up becoming the stuff of these same legends themselves, with their story being turned into a Hollywood movie (see below). Art imitating life imitating art. Given this, discovering the truth behind the myth is almost impossible, with sources telling different versions, and often contradicting each other. As such, take what follows as a best guess…

There’s something satisfyingly circular about the story of Cattle Annie and Little Britches. Two teenage girls, inspired by the questionably accurate literary exploits of Western outlaw derring-do, leave their homes and families to join those outlaws. They end up becoming the stuff of these same legends themselves, with their story being turned into a Hollywood movie (see below). Art imitating life imitating art. Given this, discovering the truth behind the myth is almost impossible, with sources telling different versions, and often contradicting each other. As such, take what follows as a best guess…

Annie was originally Anna Emmaline McDoulet, born in November 1882: some say she was the daughter to a Kansas justice of the peace, J. C. McDoulet – clearly giving her something to rebel against! – while other versions have her father a poor preacher-lawyer. After a spell working various menial jobs, she turned to crime. Initially selling liquor to Indians (something outlawed at the time), she graduated to rustling livestock, likely leading to her nickname. Meanwhile, Jennie Stevenson (a.k.a. Jennie Midkiff and Jennie Stevens), was three years Annie’s senior, and had been married and separated twice while still a teenager.

In the early eighteen-nineties, Oklahoma was still a territory, not a state – it wouldn’t become one until 1906 – and was still very much the Wild West. Bill Doolin was initially a member of the Dalton Gang but after a failed attempt to rob two banks simultaneously left four of the group dead, Doolin put his own team together, known as the “Wild Bunch”. They began a string of bank and train robberies, and in September 1893, were involved in a shootout called the “Battle of Ingalls,” which left three marshals dead. At one point were the most feared gang in the West, in part due to the efforts of dime-novelist Ned Buntline, who brought a (doubtless romanticized) version of their exploits to a popular audience.

As mentioned above, some credit Buntline’s work with inspiring our heroines to a life of crime, though as Oklahoma residents, they would likely have been well aware of the Doolin gang anyway. Another account indicates the young women met members of the Doolin gang at local dances, “and became wildly excited at the stories of the wealth and fame that would be theirs if they should turn to banditry.” [The same source notes sniffily, “Not only did they dare to wear men’s pants…but rode horses as men rode them, astride”!] Regardless of the cause, Annie and Jennie became members of the gang, with the latter being named Little Britches by Doolin.

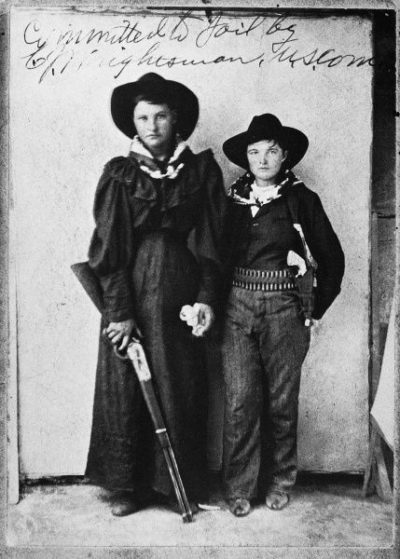

It’s unclear what the role of the girls was, but it makes sense they would have been suited to reconnaissance work, and supplying intelligence about law-enforcement activities to Doolin. For who would suspect two teenage girls of being outlaws? However, legend says, there was more to it. and the only known surviving photo of the two (above right) does suggest active participation: “Cattle Annie led her own gang of men and Little Britches was her lieutenant. Cattle Annie wore a cowboy hat and dressed and carried a rifle. Little Britches wore a cowboy hat and men’s trousers, vest and jacket, and a cartridge belt and a double holster with two six guns. Both of these ladies were tough, they carried guns like other women carried parasols, and strong men quailed when they walked into a saloon.”

In August 1895, the law finally caught up with the pair. Little Britches was arrested first, but initially escaped custody during a meal break: “She darted through the back door of the restaurant and quickly tearing off her dress, seized a horse and, mounting it, rode off.” Freedom was short-lived. For the following night, just outside Pawnee, Oklahoma. United States Marshal Bill Tilghman and Deputy Marshal Steve Burke raided the ranch where she was hiding out with Cattle Annie. With some difficulty and after an exchange of gunfire, the lawmen managed to arrest them both. Both were convicted as horse thieves and sentenced to serve their time back East, at the Farmington Reform School, in Massachusetts.

Little Britches was released early, for good behaviour, in October 1896, with Cattle Annie following 18 months later, in April 1898. Both women eventually returned to Oklahoma, married and gave up the outlaw life – though Little Britches largely dropped out of the public eye, and her eventual fate is unknown. Annie was wedded twice, having two sons with her second husband, and living in Oklahoma City from 1912 until her death in 1978 at the age of ninety-five. Her obituary in The Oklahoman made no reference to her outlaw escapades, instead saying simply, “She was a retired bookkeeper and member of American Legion Auxiliary and Olivet Baptist Church.”

The legend

★★★

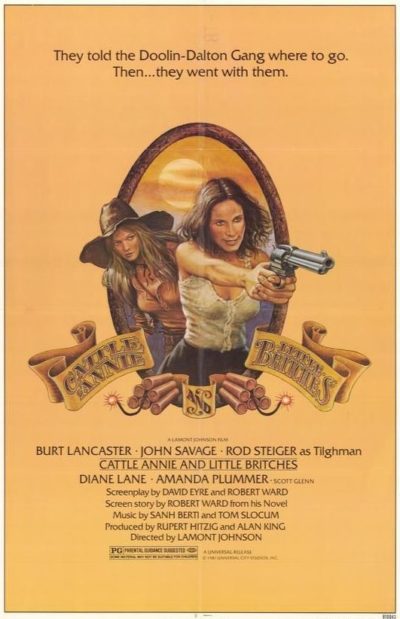

“All legends end in bullshit.”

One of the subjects here almost lived long enough to see her story on the big screen: the woman who was Cattle Annie passed away only three years before the movie version was released in April 1981. Playing her was the daughter of Christopher Plummer, Amanda, in her screen debut (she already had stage experience off-Broadway), while the role of Little Britches went to another near-newcomer who would also go on to fame in her own right, Diane Lane. It was based on Robert Ward’s book – he co-wrote the screen-play – and seems to take a fairly fast and loose approach to the facts of the pair’s lives. Though given the huge uncertainty involved in those, it’s hard to complain too much.

For example, rather than being born and brought up in Oklahoma, the duo are portrayed as making their way out to California to seek their fortune, when they’re forcibly detoured to Guthrie, OK, There, they encounter Bill Doolin (Lancaster) when he and his gang visit the town. Annie falls for gang member Bittercreek Newcomb (John Savage) and they end up being taken by him to the gang’s hideout. Their knowledge of the Doolin Gang is entirely based on the embellished stories they’ve heard about them, and they’re disappointing to find reality comes up short.

For example, rather than being born and brought up in Oklahoma, the duo are portrayed as making their way out to California to seek their fortune, when they’re forcibly detoured to Guthrie, OK, There, they encounter Bill Doolin (Lancaster) when he and his gang visit the town. Annie falls for gang member Bittercreek Newcomb (John Savage) and they end up being taken by him to the gang’s hideout. Their knowledge of the Doolin Gang is entirely based on the embellished stories they’ve heard about them, and they’re disappointing to find reality comes up short.

The man they encounter, and whose gang they join, is considerably older than the real person. Lancaster was 67 at the time, while Doolin was in his late thirties. The girls are also played significantly older: 23 during filming, Plummer was a full decade older than the real Cattle Annie. The cinematic Doolin seems increasingly weary of the whole outlaw thing, of being pursued by the relentless Bill Tilghman (Steiger), and has little or no interest in living up to his own mythology when he meets the pair. But Cattle Annie’s belief in the legend, at least somewhat reignites the fire. Though after his capture, Doolin returns to fatalism, and it’s up to the girls to stage a rescue mission, when the rest of the gang would just let their leader hang.

You get something of the hardscrabble life about the pair, and how the outlaw life is one of the few routes by which they could escape their grinding poverty. As Annie says after their failed initial attempt to follow Doolin, “I’ll not be a white nigger slave woman! I’d rather burn like a fire!” But there isn’t an enormous amount going on, and the film seems to contain a fair bit of filler, such as an impromptu game of baseball, using equipment looted during a train robbery [As a baseball fan, seems doubtful the entire group of adult men would be so oblivious of the sport as they appear. This was the mid 1890’s: the National League had been running for close to 20 years, with a team in St. Louis, one state over] Though as a meditation on the dying embers of the “Wild West,” and the gap between heroic fiction and slogging through endless rain and mud, it’s effective enough, and you can see why both young leads would go on to greater fame.

Dir: Lamont Johnson

Star: Amanda Plummer, Diane Lane, Burt Lancaster, Rod Steiger