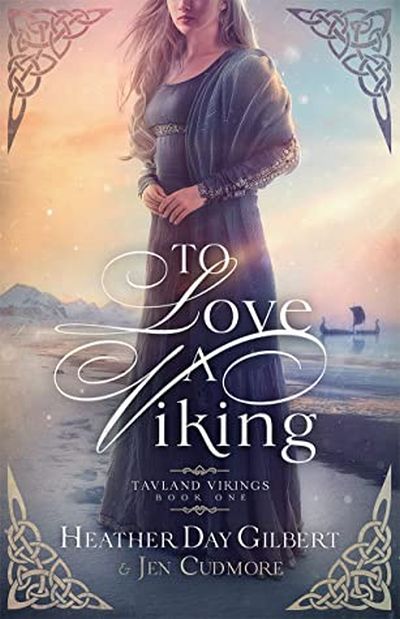

Heather Day Gilbert (who’s also a Goodreads friend, and one of my favorite writers) earned high marks from me with her earlier Vikings of the New World duology. Here, she teams up with a new-to-me fellow evangelical Christian writer, Jen Cudmore, to deliver another solid work of historical fiction (the opening volume in a projected series) set in the same era. My trade paperback ARC of this novel was generously given to me by Heather herself; no commitment that my review would be favorable was asked for or given.

Our setting here is partly in Viking-ruled northern Scotland (“Caithness”), but mostly in Scandinavia –specifically, in Tavland, a fictional large island west of Norway. (A map of the island is provided, but it has no scale and doesn’t show it in relation to any other body of land. I picture it as about midway between Norway and Iceland, and perhaps about the size of the latter.) Novels set in fictional countries aren’t unheard of (The Prisoner of Zenda comes to mind). In this case, I’d guess the reason for the device is that the authors wanted to be able to depict a Viking polity, but not to have to be bound to the historical personalities or events of any of the actual ones. The time frame is mainly 998-999 A.D. (with a short prologue set in 989). This was a time when Christianity was spreading in the northern lands, but far from universal. So polygamy and concubinage are still legal, as is slavery (and sexual exploitation of slaves). Warfare and violence are common, life expectancy can be short, and women are under a yoke of patriarchy –though in some ways it’s not as heavy a yoke as it is in the more “civilized” lands of the south in that day.

We have two co-protagonists and primary viewpoint characters here, both young women. Tavland native Ellisif, born into a land-owning family, is about 26 in 998, mother of two little girls, pregnant again, and trapped in an abusive arranged marriage. Somewhat younger at around 20, Inara was born in slavery in the islands north of Scotland, to a now-dead Tavish mother kidnapped into slavery some years earlier. Tall and strong, tough-minded and blessed with some sword skills (long story!), we meet her on the Scottish mainland hiding out from her former master. (We learn the backstory behind that only gradually.) Her goal is to become a warrior. (Although relatively rare, shield-maidens weren’t unknown in Viking society, and could be accepted as such on their merits.) Circumstances are about to bring these ladies’ life-paths together. Their viewpoints are supplemented by those of two Tavish male characters, both single: young jarl (a Viking noble title, cognate with the English “earl”) Dagar, who as a teen was engaged to Ellisif, before her parents died in a accident and her oldest brother got the bright idea of selling her like a cow or a mare to her present husband, and ship-builder and occasional warrior Hakon.

As you’ve no doubt already surmised, yes, this novel does have a romantic component –and, indeed, two romances for the price of one. :-) But it offers more than that, as serious writers know that fiction must if it depicts romantic love as a realistic (and good!) part of the totality of human life; and our two authors here are definitely serious writers. We’re looking here at family life, social relationships, implicit questions of social justice and the relationship of Christian faith to conduct; and we’re also getting a crash course (which sadly is as relevant in 2022 as it was in 998!) in the grim realities of spousal abuse and what is or isn’t a helpful way of dealing with it. (The “Word from the Authors” at the end is constructive in that regard.) Questions of gender roles, and the relationship of career goals vs. family life, are also front-and-center here, and again very relevant.

As you’ve no doubt already surmised, yes, this novel does have a romantic component –and, indeed, two romances for the price of one. :-) But it offers more than that, as serious writers know that fiction must if it depicts romantic love as a realistic (and good!) part of the totality of human life; and our two authors here are definitely serious writers. We’re looking here at family life, social relationships, implicit questions of social justice and the relationship of Christian faith to conduct; and we’re also getting a crash course (which sadly is as relevant in 2022 as it was in 998!) in the grim realities of spousal abuse and what is or isn’t a helpful way of dealing with it. (The “Word from the Authors” at the end is constructive in that regard.) Questions of gender roles, and the relationship of career goals vs. family life, are also front-and-center here, and again very relevant.

One thing that quality historical fiction such as this tends to show is that human nature and needs haven’t really changed over the centuries. (In opposition to that idea, it’s often asserted by modern would-be critics, who know little of history, that romantic love was only invented in the 1700s, and was a concept totally unknown and unimaginable before that. Plenty of primary-source evidence exists to belie that claim; it was not only a known concept, but felt by lots of people, then as now. It just wasn’t always as readily taken into account by people making the decisions about marriages then as now –and, as Ellisif and Dagar would tell us, the ones getting married weren’t always the ones making the decision.) And though this is a “romance,” it’s no bodice-ripper.

The quality of the writing here is very good, and the collaboration is seamless; I’ve read and liked several of Heather’s books, but I couldn’t tell any stylistic difference between the various parts of this book to suggest different authorship. Past-tense, third-person narration is used throughout, however, rather than Heather’s characteristic present-tense first person. (I like the one as well as the other, so that was no problem for me.) A textured picture of Viking daily life is presented, clearly based on solid research; but the research isn’t intrusive. Like Norah Lofts, our authors here avoid archaic-sounding diction in their dialogue; there are touches that suggest the setting, but we basically understand that the characters’ Old Norse is translated for us into conventional modern English with an “equivalent effect” (which explains the single use here of “okay” in conversation). References to Christian faith are natural in the circumstances of the story, and not “preachy.” Our Christian characters are Catholics (one minor character is an abbot), but denominational distinctives aren’t much in evidence. (I’d have liked more reference to the development of Inara’s faith, which is actually treated very sketchily.) Directly-described violent action scenes only occur in three places, and aren’t very graphic, but Inara shows her mettle enough to earn her “action heroine” status from me.

As a concluding note, we use “Viking” today as a general term for the ancient and early medieval Nordic inhabitants of Scandinavia, men and women, old and young. In the book, though, it’s used as it was then, as a term for a warrior. (It comes from the verbal form, “to go a-viking,” that is, trading/raiding, as inclination or circumstances dictated, in the lands to the south.) With that understanding, the title has a special meaning that will become apparent by the end of the book. :-)

Authors: Heather Day Gilbert and Jen Cudmore.

Publisher: WoodHaven Press; available through Amazon, both for Kindle and as a printed book.

A version of this review previously appeared on Goodreads.

This certainly wastes no time. Malina (Martens) regains consciousness to find herself in the trunk of a car stopped at a petrol station. Things get worse, as she discovers her legs are paralyzed, and she has a nasty wound in her lower abdomen. How did she get there? And more importantly, what can she do to escape her predicament? It’s certainly one hell of a hook, and in the way it hits the ground running – as well as its Germanic origins, almost real-time approach and the plucky heroine with a sketchy boyfriend, forced to survive on her own – reminded me of Run Lola Run. Not as brilliantly executed, of course, but well enough done to keep my interest thereafter.

This certainly wastes no time. Malina (Martens) regains consciousness to find herself in the trunk of a car stopped at a petrol station. Things get worse, as she discovers her legs are paralyzed, and she has a nasty wound in her lower abdomen. How did she get there? And more importantly, what can she do to escape her predicament? It’s certainly one hell of a hook, and in the way it hits the ground running – as well as its Germanic origins, almost real-time approach and the plucky heroine with a sketchy boyfriend, forced to survive on her own – reminded me of Run Lola Run. Not as brilliantly executed, of course, but well enough done to keep my interest thereafter.

Great poster. Solid trailer. In the light of those, unfortunately, the film can only be described as a significant disappointment. While it’s good, and occasionally

Great poster. Solid trailer. In the light of those, unfortunately, the film can only be described as a significant disappointment. While it’s good, and occasionally  For a Lifetime Original Movie, this is actually close to the best of its kind I’ve seen., but it is surely docked points for being a thoroughly shameless knock-off of a certain Liam Neeson movie, all the way down to the title. As there, we have an American abroad, searching for a teenage daughter who has been kidnapped by even more foreign sex-traffickers. They will stop at nothing –

For a Lifetime Original Movie, this is actually close to the best of its kind I’ve seen., but it is surely docked points for being a thoroughly shameless knock-off of a certain Liam Neeson movie, all the way down to the title. As there, we have an American abroad, searching for a teenage daughter who has been kidnapped by even more foreign sex-traffickers. They will stop at nothing –  I was disappointed by the lack of tentacles. However, there were certainly no shortage of teeth in this post-apocalyptic tale, which takes place decades after the arrival of monsters, from an uncertain source, has led to the collapse of civilization on Earth. The survivors are left to scratch out a fragile existence, trying to dodge the many kinds of lethal new fauna which inhabit the landscape. Askari is a young woman who forms part of one such nomadic group, but finds herself increasingly questioning the strict rules by which they operate. As punishment for breaking these laws, is sent by elders of her tribe on a hazardous mission into a long-abandoned urban area.

I was disappointed by the lack of tentacles. However, there were certainly no shortage of teeth in this post-apocalyptic tale, which takes place decades after the arrival of monsters, from an uncertain source, has led to the collapse of civilization on Earth. The survivors are left to scratch out a fragile existence, trying to dodge the many kinds of lethal new fauna which inhabit the landscape. Askari is a young woman who forms part of one such nomadic group, but finds herself increasingly questioning the strict rules by which they operate. As punishment for breaking these laws, is sent by elders of her tribe on a hazardous mission into a long-abandoned urban area. Yeah, if the above line of subtitled dialogue makes sense, this film then ups the ante, with white subs on a frequently white background, and which frequently appear to be making a bid to escape from the bottom of the picture. It’s safe to say that a decent presentation of this, perhaps with a print which doesn’t look like it was left in someone’s pocket when their suit went to the cleaners, might merit a half-star more. A few more fight sequences would help too: the ones there are, don’t lack in quality. There’s just a bit too much farcical comedy for my taste.

Yeah, if the above line of subtitled dialogue makes sense, this film then ups the ante, with white subs on a frequently white background, and which frequently appear to be making a bid to escape from the bottom of the picture. It’s safe to say that a decent presentation of this, perhaps with a print which doesn’t look like it was left in someone’s pocket when their suit went to the cleaners, might merit a half-star more. A few more fight sequences would help too: the ones there are, don’t lack in quality. There’s just a bit too much farcical comedy for my taste. This blandly inspirational tale from Australia is based on real events. In 2009, sixteen-year-old Jessica Watson (Croft) set sail out of Sydney Harbour, intending to become the youngest person ever to sail around the world solo and unassisted. 210 days later, she returned to Sydney safely. There: I’ve spoiled it for you. Oh, alright: in between departure and arrival, stuff happens. There is also some stuff which happens before she leaves, with certain parties questioning whether she is fit to carry out such a dangerous voyage, citing her lack of age and ocean-going experience. A close encounter between Jessica’s boat the Pink Lady and a freighter, while on a test sailing trip, only seemed to confirm there was good reason for concern.

This blandly inspirational tale from Australia is based on real events. In 2009, sixteen-year-old Jessica Watson (Croft) set sail out of Sydney Harbour, intending to become the youngest person ever to sail around the world solo and unassisted. 210 days later, she returned to Sydney safely. There: I’ve spoiled it for you. Oh, alright: in between departure and arrival, stuff happens. There is also some stuff which happens before she leaves, with certain parties questioning whether she is fit to carry out such a dangerous voyage, citing her lack of age and ocean-going experience. A close encounter between Jessica’s boat the Pink Lady and a freighter, while on a test sailing trip, only seemed to confirm there was good reason for concern. This bio-pic of aviator Amy Johnson appeared in British cinemas a scant eighteen months after she disappeared over the River Thames. That put its release squarely in the middle of World War II, and explains its nature which, in the later stages, could certainly be called propaganda. There’s not many other ways to explain pointed lines like “Our great sailors won the freedom of the seas. And it’s up to us to win the freedom of the skies. This is first said during a speech given by Johnson in Australia, then repeated at the end, over a rousing montage of military marching and flying. I almost expected it to end with, “Do you want to know more?”

This bio-pic of aviator Amy Johnson appeared in British cinemas a scant eighteen months after she disappeared over the River Thames. That put its release squarely in the middle of World War II, and explains its nature which, in the later stages, could certainly be called propaganda. There’s not many other ways to explain pointed lines like “Our great sailors won the freedom of the seas. And it’s up to us to win the freedom of the skies. This is first said during a speech given by Johnson in Australia, then repeated at the end, over a rousing montage of military marching and flying. I almost expected it to end with, “Do you want to know more?” I keep hoping Carano will deliver an action film reaching the quality of her debut,

I keep hoping Carano will deliver an action film reaching the quality of her debut,  This is not exactly subtle in terms of its messaging, or the underling metaphor. But to be honest, I kinda respect that. I’d probably rather know what I’m in for, from the get-go, rather than experiencing a film which thinks it’s going to be “clever”, and pull a bait and switch. Here, even the title makes it obvious enough. The ‘monster’ here is sexual violence, and should you somehow make it through the film oblivious to that, you’ll get a set of crisis helplines before the end-credits role. However, it manages to do its job without becoming misanthropic, largely by having very few male speaking characters, and is adequately entertaining on its own merits, not letting the movie drown in the message.

This is not exactly subtle in terms of its messaging, or the underling metaphor. But to be honest, I kinda respect that. I’d probably rather know what I’m in for, from the get-go, rather than experiencing a film which thinks it’s going to be “clever”, and pull a bait and switch. Here, even the title makes it obvious enough. The ‘monster’ here is sexual violence, and should you somehow make it through the film oblivious to that, you’ll get a set of crisis helplines before the end-credits role. However, it manages to do its job without becoming misanthropic, largely by having very few male speaking characters, and is adequately entertaining on its own merits, not letting the movie drown in the message. As you’ve no doubt already surmised, yes, this novel does have a romantic component –and, indeed, two romances for the price of one. :-) But it offers more than that, as serious writers know that fiction must if it depicts romantic love as a realistic (and good!) part of the totality of human life; and our two authors here are definitely serious writers. We’re looking here at family life, social relationships, implicit questions of social justice and the relationship of Christian faith to conduct; and we’re also getting a crash course (which sadly is as relevant in 2022 as it was in 998!) in the grim realities of spousal abuse and what is or isn’t a helpful way of dealing with it. (The “Word from the Authors” at the end is constructive in that regard.) Questions of gender roles, and the relationship of career goals vs. family life, are also front-and-center here, and again very relevant.

As you’ve no doubt already surmised, yes, this novel does have a romantic component –and, indeed, two romances for the price of one. :-) But it offers more than that, as serious writers know that fiction must if it depicts romantic love as a realistic (and good!) part of the totality of human life; and our two authors here are definitely serious writers. We’re looking here at family life, social relationships, implicit questions of social justice and the relationship of Christian faith to conduct; and we’re also getting a crash course (which sadly is as relevant in 2022 as it was in 998!) in the grim realities of spousal abuse and what is or isn’t a helpful way of dealing with it. (The “Word from the Authors” at the end is constructive in that regard.) Questions of gender roles, and the relationship of career goals vs. family life, are also front-and-center here, and again very relevant.