★★★½

“The dead want women.”

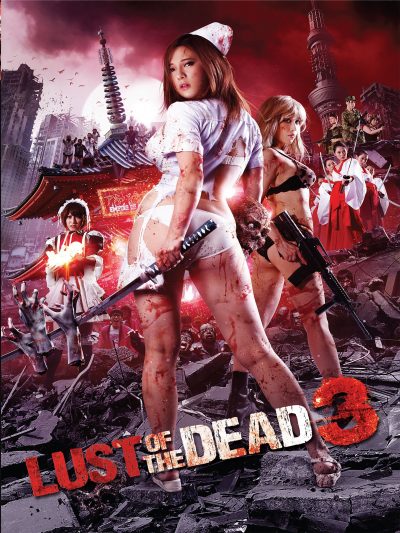

Though it may be difficult to believe such a thing, the original Japanese title for this franchise of low-budget efforts was even more politically incorrect: Rape Zombie. If ever a title change was understandable… I went into this, largely on the basis of the covers, and braced for something awful. On that basis, I was pleasantly impressed: yes, this remains staggeringly offensive. Yet it’s clearly made by people who are familiar with, and love, zombie films. There are signs of actual brains being present – and not the kind normally found in the genre, being chewed on by the shambling antagonists. Five films have been made: for now, I’m covering the first three, which are the only ones available with subtitles [because, y’know, understanding the dialogue is so important here…]

Though it may be difficult to believe such a thing, the original Japanese title for this franchise of low-budget efforts was even more politically incorrect: Rape Zombie. If ever a title change was understandable… I went into this, largely on the basis of the covers, and braced for something awful. On that basis, I was pleasantly impressed: yes, this remains staggeringly offensive. Yet it’s clearly made by people who are familiar with, and love, zombie films. There are signs of actual brains being present – and not the kind normally found in the genre, being chewed on by the shambling antagonists. Five films have been made: for now, I’m covering the first three, which are the only ones available with subtitles [because, y’know, understanding the dialogue is so important here…]

The concept is more or less the standard one: a global outbreak of some kind of illness, turning the victims into mindless creatures, who attack any non-infected person they encounter. The difference here is that the disease affects only men, and turns them into sex-crazed rapists, who will sexually assault every woman they meet. [This does an amusing job of explaining the traditional slow, shuffling gait of the zombie – here, it’s because their pants are around their ankles.] Making things worse, their semen kills their victims. Needless to say, 50% of the population is less than happy with this situation, setting up a literal war of the sexes, with the now female-led military distributing weapons to its civilian colleagues, for the battle against those pesky rape zombies.

The sex is actually the least interesting thing here – though I note, up until the very end of part 3, there is apparently no such thing as a gay zombie, who goes after other men. What is far more entertaining is the shotgun social satire at play, with the makers turning the heat up on just about everyone. Feminists. Male rights activists. The media. Politicians. Women. Men (for once, “toxic masculinity” is not hyperbole). Social networking. Idol culture. For instance, the rapidly appointed female Prime Minister proclaims, “We’re only in this situation because we allowed men to run wild with their perverted fantasies!” – then high-tails it to Hawaii, immediately she finds out North Korea has launched a nuke at Japan. When that missile flies across the skies of Tokyo, everyone just whips out their phones to take video of it.

There are four heroines in the series: two pairs, who team up following some initial distrust. Momoko (Kobayashi) ends up in hospital as the crisis breaks, after slashing her wrists at work. There, she’s befriended by nurse Nozomi (Ozawa), and when all hell breaks loose, the pair flee the hospital, and end up taking refuge in a Shinto shrine. There, they meet Kanae (Asami) and Tomoe (Aikawa), a battered housewife and a schoolgirl who have also been trying to survive the carnage. The actresses portraying all four, incidentally, are best known for their adult work, though seem to acquit themselves credibly enough with the (admittedly, fairly limited) acting required here.

There are four heroines in the series: two pairs, who team up following some initial distrust. Momoko (Kobayashi) ends up in hospital as the crisis breaks, after slashing her wrists at work. There, she’s befriended by nurse Nozomi (Ozawa), and when all hell breaks loose, the pair flee the hospital, and end up taking refuge in a Shinto shrine. There, they meet Kanae (Asami) and Tomoe (Aikawa), a battered housewife and a schoolgirl who have also been trying to survive the carnage. The actresses portraying all four, incidentally, are best known for their adult work, though seem to acquit themselves credibly enough with the (admittedly, fairly limited) acting required here.

The main…ah, thrust of the trilogy is that men’s vulnerability to the virus (or whatever it is), is dependent on their pre-epidemic sexual appetite and activity. So, the jocks and pretty boys of society are pretty much toast: who inherit the earth are the otaku. That word is probably best translated as the Japanese version of nerds/fanboys, though more derogatory in connotation there, with a particular lack of social skills. When things settle down, they form the “Akiba Empire”, blaming women for the collapse of society. They hunt the remaining “3D women” with the air of domesticated zombies. On the other side are the “Amazons”, consisting of women soldiers from the Japanese Self-Defense Forces, and other survivors, including our four heroines and scientists working on a cure.

There are a couple of further wrinkles to this scenario. Momoe ended up pregnant by her husband, but is also raped by a zombie, though survives. The resulting child – born remarkably quickly – is apparently seen as some kind of saviour by the zombies and th Akiba Empitre, who won’t attack it or Momoe. She ends up apparently driven insane, a crypto-divine figure to the otaku, worshipped as an idol – in the J-pop sense at least, performing excruciatingly bad (deliberately, I sense) musical routines for them. Meanwhile, Tomoe – spoiler – dies at the end of part one, but comes back in two and three as an American combat robot, complete with laser eyes and lightning-producing fingers. She’s sent to Japan, both to gather data and carry out something called “Project Herod”. Which is what you would expect: part three ends in a cliff-hanger, with her and Momoe in a face-off.

It would have been very easy for this to simply be a porn film with zombies in it, which I’m sure exist. As I hope the above makes clear, it isn’t. Horror fans will have fun spotting the riffs on other genre entries, such as the twist on Return of the Living Dead where a captive zombie is quizzed to its motivation: the answer here, naturally, being “More… pussy.” [As an aside, certain words are bleeped out on the Japanese soundtrack, which seems surprisingly prurient, given the nature of these films!] The second also introduces Shinji, a non-otaku seemingly unaffected by the epidemic, and his girlfriend, Maki; he becomes a key part of the scientific research, though it turns out his immunity isn’t quite what it seems. Despite the copious nudity, it all feels not dissimilar to George Romero’s Day of the Dead, located at the shadowy nexus of science and the military-industrial complex.

It would have been very easy for this to simply be a porn film with zombies in it, which I’m sure exist. As I hope the above makes clear, it isn’t. Horror fans will have fun spotting the riffs on other genre entries, such as the twist on Return of the Living Dead where a captive zombie is quizzed to its motivation: the answer here, naturally, being “More… pussy.” [As an aside, certain words are bleeped out on the Japanese soundtrack, which seems surprisingly prurient, given the nature of these films!] The second also introduces Shinji, a non-otaku seemingly unaffected by the epidemic, and his girlfriend, Maki; he becomes a key part of the scientific research, though it turns out his immunity isn’t quite what it seems. Despite the copious nudity, it all feels not dissimilar to George Romero’s Day of the Dead, located at the shadowy nexus of science and the military-industrial complex.

Overall, the trilogy manages to cram in more invention than entire later seasons of The Walking Dead. It’s especially impressive considering each film runs barely an hour – less if you discount the “Previously…” opener and closing credits. I’m not entirely convinced there needs to have been five of these films; with editing, you could likely condense them all into two, maybe two and a half, hours and lose little or no impact. There are certainly times where the intent far outstrips the available resources, to an almost painful degree, and I’m no fan of the CGI splatter which is used more often that I’d like. It remains a rare case where exploitation comes with actual smarts, and that’s a combination you just don’t see very often.

Dir: Naoyuki Tomomatsu

Star: Saya Kobayashi, Alice Ozawa, Yui Aikawa, Asami

a.k.a. Rape Zombie

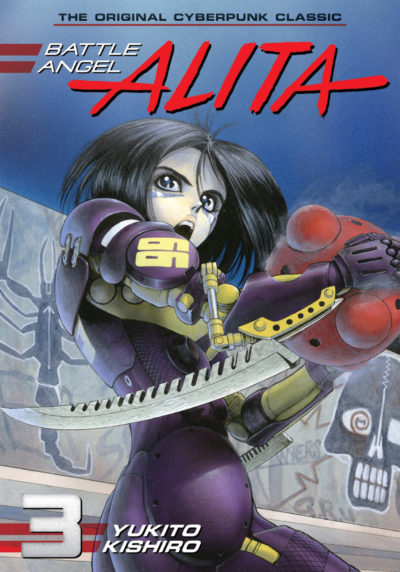

There have been two (or perhaps three) subsequent comic-book incarnations. First was Battle Angel Alita: Last Order, originally published from 2001-14 in Japan. Then came Battle Angel Alita: Holy Night and Other Stories, though this was a collection of four side-stories – hence the “perhaps three”! Most recently, we had Battle Angel Alita: Mars Chronicle (2015-17). Two of the volumes from the first incarnation were adapted into a pair of 30-minute OVAs (Original Video Animation), released in June 1993. Rumblings of a live-action version have been around almost as long, with James Cameron securing the rights to the comic in 1999, having been introduced to the property by Guillermo Del Toro. By the mid-2000’s, a script had been created, but after developing the project in parallel with Avatar, Cameron decided to devote his efforts to that instead, and Alita went on the back-burner.

There have been two (or perhaps three) subsequent comic-book incarnations. First was Battle Angel Alita: Last Order, originally published from 2001-14 in Japan. Then came Battle Angel Alita: Holy Night and Other Stories, though this was a collection of four side-stories – hence the “perhaps three”! Most recently, we had Battle Angel Alita: Mars Chronicle (2015-17). Two of the volumes from the first incarnation were adapted into a pair of 30-minute OVAs (Original Video Animation), released in June 1993. Rumblings of a live-action version have been around almost as long, with James Cameron securing the rights to the comic in 1999, having been introduced to the property by Guillermo Del Toro. By the mid-2000’s, a script had been created, but after developing the project in parallel with Avatar, Cameron decided to devote his efforts to that instead, and Alita went on the back-burner.

I used to read a

I used to read a  wever, there’s still an amazing amount going on in terms of story-line and universe-building. You can easily see how the feature film will only be able to cover perhaps one-quarter of the series. I presume it will begin with the origin story, in which Ido finds the head of Alita in the scrapyard beneath the floating city of Tiphares, and gives it a cybernetic body. He’s a part-time bounty hunter, only to find out quickly, the combat abilities of his new charge far surpass his own. Unfortunately, she has little or no memory of her prior life; where she got these skills and how she ended up in the scrapyard is only revealed well into the series.

wever, there’s still an amazing amount going on in terms of story-line and universe-building. You can easily see how the feature film will only be able to cover perhaps one-quarter of the series. I presume it will begin with the origin story, in which Ido finds the head of Alita in the scrapyard beneath the floating city of Tiphares, and gives it a cybernetic body. He’s a part-time bounty hunter, only to find out quickly, the combat abilities of his new charge far surpass his own. Unfortunately, she has little or no memory of her prior life; where she got these skills and how she ended up in the scrapyard is only revealed well into the series.

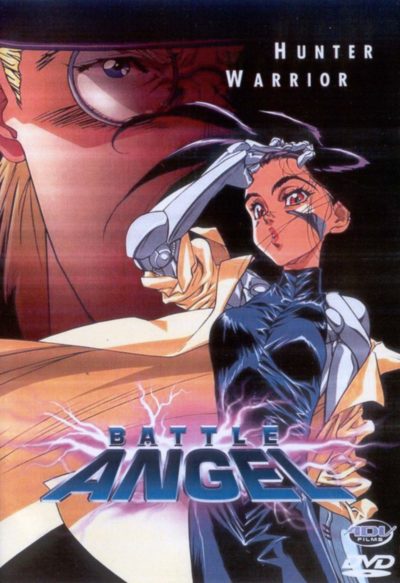

Watching this after having read the manga version, it feels like the anime version can do little more than scratch the surface of the world of Tiphares, in the barely fifty minutes it has to work with across its two OVA (Original Video Animation) volumes. The stories here, originally released in 1993, cover the first two section of the manga, and it looks like much of what we see here will also be included in the live-action film next February. Slightly confusing matters, is the way this uses the original Japanese names. So Tiphares becomes Zalem here, and Hugo is Yugo. Most oddly, the heroine is not called Alita – hence the absence of her name from the title – but Gally. To avoid further confusion, I’m going to be consistent with our other articles on the topic, and stick to the translated ones for what follows.

Watching this after having read the manga version, it feels like the anime version can do little more than scratch the surface of the world of Tiphares, in the barely fifty minutes it has to work with across its two OVA (Original Video Animation) volumes. The stories here, originally released in 1993, cover the first two section of the manga, and it looks like much of what we see here will also be included in the live-action film next February. Slightly confusing matters, is the way this uses the original Japanese names. So Tiphares becomes Zalem here, and Hugo is Yugo. Most oddly, the heroine is not called Alita – hence the absence of her name from the title – but Gally. To avoid further confusion, I’m going to be consistent with our other articles on the topic, and stick to the translated ones for what follows. ★★★½

★★★½ If she were the only candidate, this might end up being a bit of a borderline entry, but over the 24 episodes in the two series (there’s another five-episode arc I haven’t seen, Roberta’s Blood Trail, which came out in 2010), Revy is joined by a number of other, morally ambiguous women, all of whom are more than comfortable with firearms:

If she were the only candidate, this might end up being a bit of a borderline entry, but over the 24 episodes in the two series (there’s another five-episode arc I haven’t seen, Roberta’s Blood Trail, which came out in 2010), Revy is joined by a number of other, morally ambiguous women, all of whom are more than comfortable with firearms:

While not the first to be released, this was the first movie directed by Miike, who would go on to become one of the most prolific – yet, still, critically-lauded – directors to come out of Japan in the last quarter-century. Perhaps this is well-informed hindsight: yet, if still pretty basic in its content, it does feels at least somewhat above what you would expect from a straight-to-video movie by a first-time director.

While not the first to be released, this was the first movie directed by Miike, who would go on to become one of the most prolific – yet, still, critically-lauded – directors to come out of Japan in the last quarter-century. Perhaps this is well-informed hindsight: yet, if still pretty basic in its content, it does feels at least somewhat above what you would expect from a straight-to-video movie by a first-time director. The above line of dialogue is a perfect litmus test for what you’ll think of this. If your reaction is a derisive snort, this pair of hour-long items – I have qualms about calling them anything as high-minded as “feature films” – is probably not for you. And I cheerfully admit, snorting is probably the default, and understandable, reaction. If, on the other hand, you are giddy with anticipation at the very thought, then I probably cannot recommend it highly enough.

The above line of dialogue is a perfect litmus test for what you’ll think of this. If your reaction is a derisive snort, this pair of hour-long items – I have qualms about calling them anything as high-minded as “feature films” – is probably not for you. And I cheerfully admit, snorting is probably the default, and understandable, reaction. If, on the other hand, you are giddy with anticipation at the very thought, then I probably cannot recommend it highly enough.

A bus full of Japanese schoolgirls includes the quiet, poetry-writing Mitsuko (Triendl), who drops her pen. Bending down to pick it up, she thus survives the lethal gust of wind which neatly bisects, not only the bus, but the rest of her classmates. Ok, film: safe to say, you have acquired our attention. [Not for the first time the director has managed this: the opening scene of his Suicide Circle is one we still vividly remember, 15 years later]

A bus full of Japanese schoolgirls includes the quiet, poetry-writing Mitsuko (Triendl), who drops her pen. Bending down to pick it up, she thus survives the lethal gust of wind which neatly bisects, not only the bus, but the rest of her classmates. Ok, film: safe to say, you have acquired our attention. [Not for the first time the director has managed this: the opening scene of his Suicide Circle is one we still vividly remember, 15 years later] I strongly prefer the alternative name (as given in the credits below, though in some territories this was also known as Inglorious Zombie Hunters) – it’s one of the finest exploitation titles of all time, both describing exactly what the film is about, while simultaneously reeling in the potential viewer. Certainly beats something which sounds more like an Asylum “mockbuster” version of a certain, snarky Marvel superhero. If the product itself doesn’t quite live up to it’s own name, this mostly a case of, really, how could it?

I strongly prefer the alternative name (as given in the credits below, though in some territories this was also known as Inglorious Zombie Hunters) – it’s one of the finest exploitation titles of all time, both describing exactly what the film is about, while simultaneously reeling in the potential viewer. Certainly beats something which sounds more like an Asylum “mockbuster” version of a certain, snarky Marvel superhero. If the product itself doesn’t quite live up to it’s own name, this mostly a case of, really, how could it? There are times when a film doesn’t deliver anything close to what the sleeve promises. This would be one of those times. However, in this case, while disappointed, I can’t claim it was an entire waste of my time. Or, at least, it wasn’t a waste of very

There are times when a film doesn’t deliver anything close to what the sleeve promises. This would be one of those times. However, in this case, while disappointed, I can’t claim it was an entire waste of my time. Or, at least, it wasn’t a waste of very