★★½

Lady Snowblood

I’ll be honest: I was disappointed. I’d been looking forward to seeing this for a long while, but when we finally cranked it up on Monday, found it pretty dull. Truth be told, Chris was giving it loud Z’s by the end of the film, and I spent a few minutes closing my eyes and just listening to the dialogue. Which, since it was in Japanese, isn’t a good sign either. This was a surprise. A lot of people, whose views I generally respect, really like it, such as mandiapple.com, who called it “nothing short of a masterpiece.” Reading that, I had to check they were reviewing the same film. Because, personally, while its influence on Kill Bill is undeniable, that is a far more effective piece of work.

I’ll be honest: I was disappointed. I’d been looking forward to seeing this for a long while, but when we finally cranked it up on Monday, found it pretty dull. Truth be told, Chris was giving it loud Z’s by the end of the film, and I spent a few minutes closing my eyes and just listening to the dialogue. Which, since it was in Japanese, isn’t a good sign either. This was a surprise. A lot of people, whose views I generally respect, really like it, such as mandiapple.com, who called it “nothing short of a masterpiece.” Reading that, I had to check they were reviewing the same film. Because, personally, while its influence on Kill Bill is undeniable, that is a far more effective piece of work.

The plot in both is needlessly-convoluted, but it has much more of a negative impact here. Here is the story, in chronological order. In late 19th-century Japan, a mother sees her husband and young son slaughtered by a group of four con-artists; she is kidnapped and raped over a period of several days before being abandoned. She vows revenge, but is arrested after killing only one of the four, and sent to prison for life. There, she has a baby daughter, Yuki, spawned for the sole purpose of continuing the revenge. After the mother dies in jail, Yuki is released with another prisoner, and begins her training under a tough Buddhist priest (Nishimura). When she reaches her twentieth birthday, she leaves, to start her mission.

The problems here are multiple, not least that Yuki is just too cold. She might as well be an automaton, as she progresses on her vengeance, showing no emotion or feeling, and it’s hard to feel empathy for her. Yes, she is supposed to be a cold-hearted killing machine, but the performance here is devoid of all humanity. There’s nothing personal here either. Yuki is not the victim; the events in question occurred before she was even conceived, giving her no direct stake in proceedings – she is simply a tool, wielded from beyond the grave by a mother she never really knew. Contrast Kill Bill, where the Bride sees her husband-to-be slaughtered at the altar. As motivation, it’s far superior and resonates much more with the audience.

Then there’s the action, which is second-rate at best. It may have seemed cutting-edge when the film was released in 1973. Approaching forty years later… Not so much. There’s little sense that anyone – good or bad – has true sword skills, and the battles are largely brief and perfunctory. Admittedly, the arterial spray is enthusiastic – clearly the high blood-pressure epidemic affecting Japan is not a new phenomena – and looks very pretty on the snow backdrop which is frequently used. However, that can only go some way to overcoming the flaws in the characterization: one suspects the original manga, by Kazuo Koike (who also did Lone Wolf and Cub), perhaps had more room to be better developed in this area. And while we’re at it, what’s with the anachronistic jazz soundtrack, dating from a good half-century after this is set? Any sense of period atmosphere is completely destroyed, every time it cranks up.

Then there’s the action, which is second-rate at best. It may have seemed cutting-edge when the film was released in 1973. Approaching forty years later… Not so much. There’s little sense that anyone – good or bad – has true sword skills, and the battles are largely brief and perfunctory. Admittedly, the arterial spray is enthusiastic – clearly the high blood-pressure epidemic affecting Japan is not a new phenomena – and looks very pretty on the snow backdrop which is frequently used. However, that can only go some way to overcoming the flaws in the characterization: one suspects the original manga, by Kazuo Koike (who also did Lone Wolf and Cub), perhaps had more room to be better developed in this area. And while we’re at it, what’s with the anachronistic jazz soundtrack, dating from a good half-century after this is set? Any sense of period atmosphere is completely destroyed, every time it cranks up.

What works is mostly the visual style, and it’s soundly put together from a technical aspect. Kaji, who plays the adult Yuki, is also solid enough, though was probably better – even if she said less! – in the Female Convict Scorpion series [I must get round to reviewing the excellent Jailhouse 41 here some time, though it won’t be till after we move house in October, and the DVD re-surfaces…]. I also liked the chaste purity here: Yuki doesn’t have any real relationships at all – she lives purely for revenge. However, I feel much the same way about this, that I did about the original Night of the Living Dead. While it certainly deserves to be respected for its influential place in the history of the genre, it feels as if the elements seen here have been revisited with greater success, by those who followed in its foot-steps.

Dir: Toshiya Fujita

Star: Meiko Kaji, Ko Nishimura, Toshio Kurosawa, Masaaki Daimon

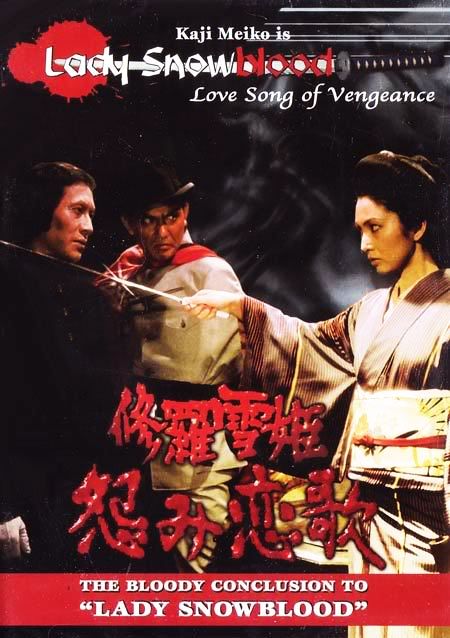

★★

Lady Snowblood 2: Love Song of Vengeance

I was hoping that the second film would show me why this series has such a solid reputation, but was even more disappointed by the sequel than the original. There’s a striking opening, where Yuki basically walks out of an ambush, hardly bothering even to pay attention to the men circling her – except to slaughter them. Unfortunately, it’s pretty much downhill from there, with proceedings getting badly bogged down in even more of the political shenanigans that we saw in part one. Yuki is arrested and sentenced to death for her 37(!) murders, but is rescued by the chief of the secret police, Kikui Seishiro (Kishida), who sends her on a mission against nihilist Ransui Tokunaga (Itami), perceived as a threat to the order of things.

I was hoping that the second film would show me why this series has such a solid reputation, but was even more disappointed by the sequel than the original. There’s a striking opening, where Yuki basically walks out of an ambush, hardly bothering even to pay attention to the men circling her – except to slaughter them. Unfortunately, it’s pretty much downhill from there, with proceedings getting badly bogged down in even more of the political shenanigans that we saw in part one. Yuki is arrested and sentenced to death for her 37(!) murders, but is rescued by the chief of the secret police, Kikui Seishiro (Kishida), who sends her on a mission against nihilist Ransui Tokunaga (Itami), perceived as a threat to the order of things.

That’s because Tokanaga and his wife are in possession of a document that could seriously embarrass the government, by proving their involvement in the deaths of Tokunaga’s partners. When Yuki discovers this, she switches sides, though Tokunaga is arrested, tortured and, when he fails to give up the document’s location, injected with bubonic plague [interestingly, this is a decade before the biological weapons work of Unit 731 during WW2 became public knowledge in Japan] and dumped in the slums as a warning to others. Yuki teams up with Tokunaga’s estranged brother, and sets out to take revenge on the government forces responsible for his death.

This is set just after the Russo-Japanese war of 1905, and I’ve a feeling is meant in some way to parallel the political situation of the 1970’s. However, all such sentiment is entirely wasted on Western viewers watching it almost forty years after it was made. If you’re looking at this as an action movie, it plays out in a manner best described as turgid, with very sporadic action, to such an extent that it hardly qualifies as such at all – if it weren’t for the original, I doubt I’d be covering it here. Even the arterial gushiness seems to be less unenthusiastic and sprayful than previously.

On the other hand, Kaji’s portrayal is more emotionally-disengaged this time, and it’s even harder to develop sympathy for a character engaged in some kind of obscure political activism, rather than personal revenge. It’s what perhaps makes this one’s closest cousin V For Vendetta, with samurai swords. And, in case you were wondering, that is not meant to be much of an endorsement. I’d say you are far better off watching the futuristic remake, The Princess Blade or even the better entries in the Crimson Bat series than either of these films, and given my high hopes coming into these, based on their reputation, that’s extremely disappointing.

Dir: Toshiya Fujita

Star: Meiko Kaji, Juzo Itami, Kazuko Yoshiyuki, Shin Kishida

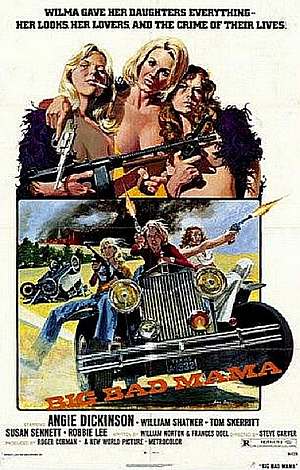

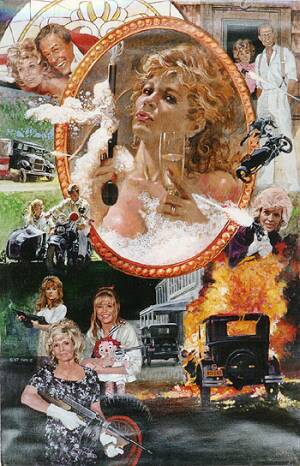

With B-movie entrepreneur Roger Corman getting honoured at the Oscars earlier this month, it seems appropriate to pop on one of his classic productions, starring Dickinson, who was just about to become a star in one of the first shows with a female law-enforcement lead, Police Woman. The truth is, however, that this doesn’t have much more to offer beyond Dickinson: while she holds the film together with her steely resolve, and proves that sexy doesn’t stop at 40, the rest of it offers nothing as substantial. It’s a basic enough plot: she plays Wilma McClatchie, a single mom bringing up her two teenage daughters in Depression-era rural America. They fall into a life of crime, in part because they happen to be trying to cash a fraudulent check in a bank when it gets robbed by Fred Diller (Skerritt). They also team up with gentleman con-artist William Baxter (Shatner), but things go awry when they pull of their last big heist, kidnapping the daughter of a millionaire.

With B-movie entrepreneur Roger Corman getting honoured at the Oscars earlier this month, it seems appropriate to pop on one of his classic productions, starring Dickinson, who was just about to become a star in one of the first shows with a female law-enforcement lead, Police Woman. The truth is, however, that this doesn’t have much more to offer beyond Dickinson: while she holds the film together with her steely resolve, and proves that sexy doesn’t stop at 40, the rest of it offers nothing as substantial. It’s a basic enough plot: she plays Wilma McClatchie, a single mom bringing up her two teenage daughters in Depression-era rural America. They fall into a life of crime, in part because they happen to be trying to cash a fraudulent check in a bank when it gets robbed by Fred Diller (Skerritt). They also team up with gentleman con-artist William Baxter (Shatner), but things go awry when they pull of their last big heist, kidnapping the daughter of a millionaire. Earlier

Earlier

1. In the late 19th century, a number of women were among the active leaders of the Russian nihilist organization Narodnaya Volya (People’s Will), best known for their assassination of Czar Alexander II in 1981. That was organized by a woman, Sophia Perovskaya, with another female member of the Executive Committee, Vera Figner (left) also participating. Four years previously, Vera Zasulich (right) shot and seriously wounded Colonel Theodore Trepov, the hated governor of St. Petersburg.

1. In the late 19th century, a number of women were among the active leaders of the Russian nihilist organization Narodnaya Volya (People’s Will), best known for their assassination of Czar Alexander II in 1981. That was organized by a woman, Sophia Perovskaya, with another female member of the Executive Committee, Vera Figner (left) also participating. Four years previously, Vera Zasulich (right) shot and seriously wounded Colonel Theodore Trepov, the hated governor of St. Petersburg. 3. In Cuba, Celia Sánchez (right, with fellow revolutionary Haydée Santamaría) became one of the earliest members of the 26th of July Movement, joining the struggle after the coup against President Batista in 1952. After Fidel Castro was jailed, she became the rebel leader in the mountainous Sierra region of eastern Cuba, and was called by Castro, “the greatest guerrilla fighter and the most outstanding leader of the Cuban Revolution.” was one of the first women to assemble a combat squad during the revolution[. She was tasked with making all the necessary arrangements throughout the southwest coast region of Cuba, for the Granma landing, and was responsible for organising reinforcements once the revolutionaries landed.

3. In Cuba, Celia Sánchez (right, with fellow revolutionary Haydée Santamaría) became one of the earliest members of the 26th of July Movement, joining the struggle after the coup against President Batista in 1952. After Fidel Castro was jailed, she became the rebel leader in the mountainous Sierra region of eastern Cuba, and was called by Castro, “the greatest guerrilla fighter and the most outstanding leader of the Cuban Revolution.” was one of the first women to assemble a combat squad during the revolution[. She was tasked with making all the necessary arrangements throughout the southwest coast region of Cuba, for the Granma landing, and was responsible for organising reinforcements once the revolutionaries landed. 6. Fusako Shigenobu (left, with colleague Kozo Okamoto) was one of the founders and leaders of the Japanese Red Army. She is now serving 20 years for kidnapping embassy workers during a 1974 Japanese Red Army operation, she is also believed to have played key roles in other hijackings and bomb attacks. Reputedly ordered the murder, by burial alive, of a pregnant woman colleague for being “too bourgeois.” Another left-wing radical, Hiroko Nagata, while acting as vice-chairman of the United Red Army, directed the killing of 14 members of the group by beatings or hypothermia, during a 1972 purge. With friends like that, who needs enemies?

6. Fusako Shigenobu (left, with colleague Kozo Okamoto) was one of the founders and leaders of the Japanese Red Army. She is now serving 20 years for kidnapping embassy workers during a 1974 Japanese Red Army operation, she is also believed to have played key roles in other hijackings and bomb attacks. Reputedly ordered the murder, by burial alive, of a pregnant woman colleague for being “too bourgeois.” Another left-wing radical, Hiroko Nagata, while acting as vice-chairman of the United Red Army, directed the killing of 14 members of the group by beatings or hypothermia, during a 1972 purge. With friends like that, who needs enemies? 9. During their struggle for independence from Spain, Basque separatist group ETA had some infamous women members. These include Maria Dolores Gonzalez (“Yoyez”), who was later assassinated by the group as a reprisal for having left. Also high in their power structure was María Soledad Iparragirre, known as ‘Anboto’, whose exploits allegedly included the murder of a Spanish army Lieutenant and a car bomb explosion against a military bus, that killed seven.

9. During their struggle for independence from Spain, Basque separatist group ETA had some infamous women members. These include Maria Dolores Gonzalez (“Yoyez”), who was later assassinated by the group as a reprisal for having left. Also high in their power structure was María Soledad Iparragirre, known as ‘Anboto’, whose exploits allegedly included the murder of a Spanish army Lieutenant and a car bomb explosion against a military bus, that killed seven.

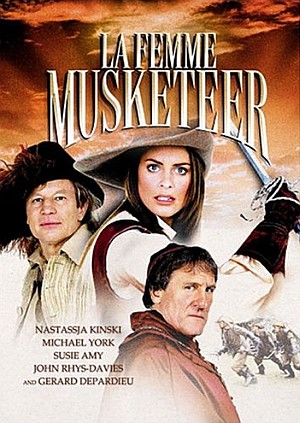

While not the first film to give D’Artagnan a daughter – the fairly self-explanatory D’Artagnan’s Daughter got there a decade before, with Sophie Marceau in the role – this is still entertaining enough, though at 171 minutes, probably too long. Valentine (Amy) heads to Paris to join the King’s guards, only to find herself framed for murder after coming into possession of a letter that could bring down the monarch. Fortunately, the other Musketeers also had children who followed in their father’s footsteps, so she has help as she tries to thwart the evil plans of Cardinal Mazarin (Depardieu) and his henchman Villeroi (Pirae).

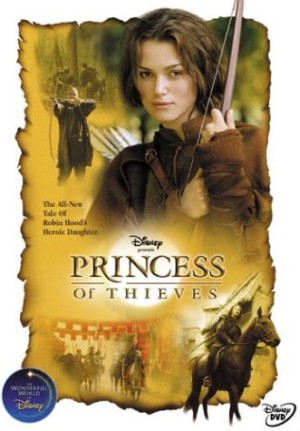

While not the first film to give D’Artagnan a daughter – the fairly self-explanatory D’Artagnan’s Daughter got there a decade before, with Sophie Marceau in the role – this is still entertaining enough, though at 171 minutes, probably too long. Valentine (Amy) heads to Paris to join the King’s guards, only to find herself framed for murder after coming into possession of a letter that could bring down the monarch. Fortunately, the other Musketeers also had children who followed in their father’s footsteps, so she has help as she tries to thwart the evil plans of Cardinal Mazarin (Depardieu) and his henchman Villeroi (Pirae). Back before Pirates of the Caribbean made Knightley a household name, and even before Bend It Like Beckham made her an

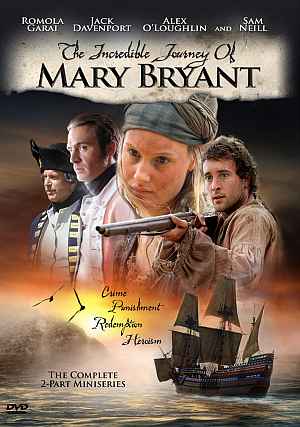

Back before Pirates of the Caribbean made Knightley a household name, and even before Bend It Like Beckham made her an  Most Aussies won’t thank you for mentioning it, but the colony was originally populated largely by the dregs of British society. Prisoners were shipped Down Under, thereby alleviating jail overcrowding and providing a cheap labour source for the new world. This mini-series recounts the story of one such unwilling emigrant, Mary Bryant, shipped off to Oz for a petty theft. She gives birth to one child en route, and has another there, but when starvation threatens her family, she plans a daring escape, and convinces her co-convicts to help, even though they’re 3,000 miles from the nearest safe haven.

Most Aussies won’t thank you for mentioning it, but the colony was originally populated largely by the dregs of British society. Prisoners were shipped Down Under, thereby alleviating jail overcrowding and providing a cheap labour source for the new world. This mini-series recounts the story of one such unwilling emigrant, Mary Bryant, shipped off to Oz for a petty theft. She gives birth to one child en route, and has another there, but when starvation threatens her family, she plans a daring escape, and convinces her co-convicts to help, even though they’re 3,000 miles from the nearest safe haven. Here be historical spoilers I was surprised how close this was to the truth. Bryant was a Cornish convict, transported to Australia, who did take part in a break-out. Though captured in Timor and returned to Britain, there was indeed a public outcry, and those involved were pardoned. The main dramatic invention is Clarke’s relationship with Mary; he certainly didn’t kill her husband, who actually died of natural causes during the voyage back to Britain. The nod to James Boswell is legitimate too, as he was among those who campaigned for her release. Various books have been written about her; Google is your friend if you want to find out about these.

Here be historical spoilers I was surprised how close this was to the truth. Bryant was a Cornish convict, transported to Australia, who did take part in a break-out. Though captured in Timor and returned to Britain, there was indeed a public outcry, and those involved were pardoned. The main dramatic invention is Clarke’s relationship with Mary; he certainly didn’t kill her husband, who actually died of natural causes during the voyage back to Britain. The nod to James Boswell is legitimate too, as he was among those who campaigned for her release. Various books have been written about her; Google is your friend if you want to find out about these. A Roger Corman production. Those four words cover much turf, both good and bad; this inclines toward the latter, simply because it takes an interesting premise, and goes next to nowhere with it. It’s less a sequel to, than a remake of the 1974 film, also starring Dickinson, which is generally believed to be superior. However, that isn’t on heavy cable rotation this month, so you’re stuck with the follow-up. Dickinson plays Wilma McClatchie, evicted from her home by uncaring businessman Morgan Crawford, and whose husband is killed in the process. She and her daughters Billie-Jean and Polly take up a life outside the law, but when Crawford makes a run for governor, their crimes take on a political perspective, as they aim to sabotage his campaign.

A Roger Corman production. Those four words cover much turf, both good and bad; this inclines toward the latter, simply because it takes an interesting premise, and goes next to nowhere with it. It’s less a sequel to, than a remake of the 1974 film, also starring Dickinson, which is generally believed to be superior. However, that isn’t on heavy cable rotation this month, so you’re stuck with the follow-up. Dickinson plays Wilma McClatchie, evicted from her home by uncaring businessman Morgan Crawford, and whose husband is killed in the process. She and her daughters Billie-Jean and Polly take up a life outside the law, but when Crawford makes a run for governor, their crimes take on a political perspective, as they aim to sabotage his campaign. The story of Ma Barker, legendary leader of a bank-robbing gang consisting mainly of her sons, has inspired multiple movies, from relatively well-known (Roger Corman’s Bloody Mama) to obscurist (Ma Barker’s Killer Brood from 1960). They all play

The story of Ma Barker, legendary leader of a bank-robbing gang consisting mainly of her sons, has inspired multiple movies, from relatively well-known (Roger Corman’s Bloody Mama) to obscurist (Ma Barker’s Killer Brood from 1960). They all play  The daughter of Owen “Dubhdarra” (black oak) O’Malley, famous Irish sea captain, is somebody whose life could easily be made into a film. Known as Gráinne Ní Mháille in her native tongue, I suspect the English version, Grace O’Malley, would be a little more manageable for cinemagoers, and so, that’s the form we’ll use here. She was born in 16th-century Ireland, which at the time was largely allowed to operate independently of England. However, during her lifetime, that gradually changed, and it’s this which was behind many of the turning points in her life.

The daughter of Owen “Dubhdarra” (black oak) O’Malley, famous Irish sea captain, is somebody whose life could easily be made into a film. Known as Gráinne Ní Mháille in her native tongue, I suspect the English version, Grace O’Malley, would be a little more manageable for cinemagoers, and so, that’s the form we’ll use here. She was born in 16th-century Ireland, which at the time was largely allowed to operate independently of England. However, during her lifetime, that gradually changed, and it’s this which was behind many of the turning points in her life.

Finally the English Queen agreed and Grace came to court to make her pitch (left). She horrified them by addressing the Queen as an equal – Grace’s use of Latin, the language of nobles, would have impressed the Queen. She made a point of saying that they were much alike, both prepared to fight to keep their possessions. Grace referred to the way Elizabeth had joined her army at Tilbury, when the Spanish Armada threatened to invade in 1588. She made a difference too, as her rousing speech did wonders for the moral of her, up till then, pessimistic troops. [It is historical fact that Elizabeth was fond of hunting, and an excellent shot with a crossbow, so it is possible she may well have got involved if the Spanish had landed.] Around the same time, some Spaniards were shipwrecked in Ireland and slaughtered by Grace. A scene of each of these incidents would help illustrate that they did have a lot in common.

Finally the English Queen agreed and Grace came to court to make her pitch (left). She horrified them by addressing the Queen as an equal – Grace’s use of Latin, the language of nobles, would have impressed the Queen. She made a point of saying that they were much alike, both prepared to fight to keep their possessions. Grace referred to the way Elizabeth had joined her army at Tilbury, when the Spanish Armada threatened to invade in 1588. She made a difference too, as her rousing speech did wonders for the moral of her, up till then, pessimistic troops. [It is historical fact that Elizabeth was fond of hunting, and an excellent shot with a crossbow, so it is possible she may well have got involved if the Spanish had landed.] Around the same time, some Spaniards were shipwrecked in Ireland and slaughtered by Grace. A scene of each of these incidents would help illustrate that they did have a lot in common. Another interesting tale is told about an incident on the way home to Ireland. She stopped at Howth Castle, where hospitality dictated she should have been offered a meal and a place to stay. But she was told the lord was dining, and wasn’t to be disturbed: an infuriated Grace was leaving, when she met the lord’s son, who was returning to the castle. She kidnapped him, and as the terms for his return, demanded that in future, anyone who asked at Howth Castle would get food and a bed. The tradition continues to this day; the family that lives there still has an extra seat for dinner, just in case…

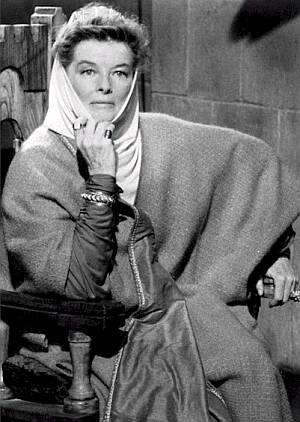

Another interesting tale is told about an incident on the way home to Ireland. She stopped at Howth Castle, where hospitality dictated she should have been offered a meal and a place to stay. But she was told the lord was dining, and wasn’t to be disturbed: an infuriated Grace was leaving, when she met the lord’s son, who was returning to the castle. She kidnapped him, and as the terms for his return, demanded that in future, anyone who asked at Howth Castle would get food and a bed. The tradition continues to this day; the family that lives there still has an extra seat for dinner, just in case… If Eleanor of Aquitaine is perhaps best known through the Oscar-winning portrayal of Katherine Hepburn (right) in The Lion in Winter, she was one of the richest and most powerful women of the Middle Ages in her own right. She was married twice, to the Kings of France and England, and she survived to see two sons also became monarchs. But Eleanor’s own life was both long – she lived into her eighties, remarkable for the era – and colourful.

If Eleanor of Aquitaine is perhaps best known through the Oscar-winning portrayal of Katherine Hepburn (right) in The Lion in Winter, she was one of the richest and most powerful women of the Middle Ages in her own right. She was married twice, to the Kings of France and England, and she survived to see two sons also became monarchs. But Eleanor’s own life was both long – she lived into her eighties, remarkable for the era – and colourful.

It was Eleanor who looked after things when he was gone; a contemporary writer, Ralph of Diceto, says: “He issued instructions to the princes of the realm, almost in the style of a general edict, that the queen’s word should be law in all matters.” This is significant, since of Richard’s ten year reign, only six months were actually spent in England. She did make one major overseas trip during this period, arranging for Richard to marry Berengaria of Navarre. But he wasn’t waiting around to get hitched to anyone – he was off to Palestine. It was up to Eleanor, now almost 70, to ride over the Pyrenees, collect the prospective bride from her home, and then travel with her through Spain, France and Italy to Sicily where Richard and his army were camped.

It was Eleanor who looked after things when he was gone; a contemporary writer, Ralph of Diceto, says: “He issued instructions to the princes of the realm, almost in the style of a general edict, that the queen’s word should be law in all matters.” This is significant, since of Richard’s ten year reign, only six months were actually spent in England. She did make one major overseas trip during this period, arranging for Richard to marry Berengaria of Navarre. But he wasn’t waiting around to get hitched to anyone – he was off to Palestine. It was up to Eleanor, now almost 70, to ride over the Pyrenees, collect the prospective bride from her home, and then travel with her through Spain, France and Italy to Sicily where Richard and his army were camped.