Literary rating: ★★★★

Kick-butt quotient: ☆☆☆½

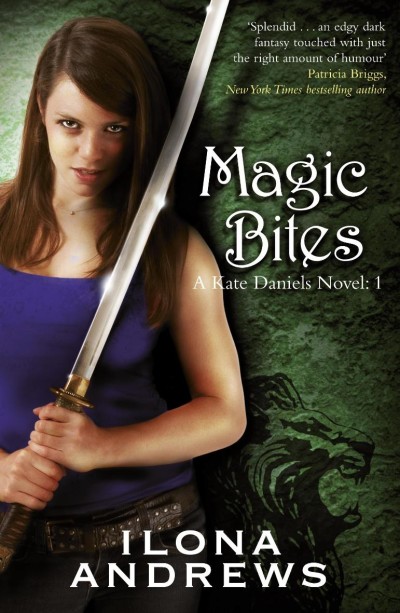

“Ilona Andrews” is the pen name of a husband-and-wife author team; her first name really is Ilona. (There’s some confusion about his; “About the Authors” in the edition I read gives it as Andrew, but a comment in the extra material uses Gordon, as does the author page on Goodreads. Possibly Andrew Gordon?) They’ve attained considerable success with their urban fantasy Kate Daniels series. Since I’m a fan of both supernatural fiction and strong, kick-butt heroines, it isn’t surprising that the series had been on my radar for a long time before I read this opening volume, as a buddy read with a friend. It didn’t disappoint!

“Ilona Andrews” is the pen name of a husband-and-wife author team; her first name really is Ilona. (There’s some confusion about his; “About the Authors” in the edition I read gives it as Andrew, but a comment in the extra material uses Gordon, as does the author page on Goodreads. Possibly Andrew Gordon?) They’ve attained considerable success with their urban fantasy Kate Daniels series. Since I’m a fan of both supernatural fiction and strong, kick-butt heroines, it isn’t surprising that the series had been on my radar for a long time before I read this opening volume, as a buddy read with a friend. It didn’t disappoint!

Our female co-author here is Russian-born, a fact reflected in our fictional heroine’s upbringing. An orphan, Kate was raised by a now-deceased Russian foster father, who named her (Kate is short for Ekaterina, and he made up “Daniels”). Ilona probably provides the authorial pair’s knowledge of Russian folklore, which figures prominently in both this novel and the bonus story. (That’s a plus for me, as it’s an area of folklore I know little about, and enjoy learning more; the authors also draw on a wide range of mythologies in developing the series.) Our setting here is Atlanta, and though the writers currently live in Austin, TX, their handling of Atlanta geography seems assured enough to suggest first-hand knowledge or very good research. (Though I might be easy to fool on that score, since I’ve never been to Atlanta myself!)

To be sure, this isn’t the early 21st-century Atlanta we know. The 24-year-old Kate lives in the mid-21st-century, and grew up in a world that for decades has been transformed by a phenomenon called the Shift. Unpredictable, periodic surges of magic flare through the world, temporarily knocking high technology out of service and bringing to life spells, wards, ley lines, and other assorted magical phenomena. A weakness of this book is that it doesn’t do much to explore the obvious intellectual, social and cultural changes this upheaval would have caused; they’re only hinted at. Another weakness is that the premise itself, although it’s certainly one of the most original in literature, isn’t entirely convincing (Kate’s suggested explanation isn’t plausible, IMO, but she only says it’s the prevailing theory, not that it’s a fact). But neither of these areas are central to the authors’ purpose. They simply want to set up a highly novel, ultra-dangerous and somewhat Balkanized world in which there’s plenty of scope for adventure for a mercenary like Kate. In that respect, they succeed admirably.

Kate’s something of a mystery woman; she’s close-mouthed about her heritage, but it includes some significant inborn magical ability. It’s not, however, anything that gives her invincible superhuman powers; she’s mortal, hurts and bleeds, and has to rely on her wits and physical conditioning in a fight, the same as any other human would. (She also has a magic sword, Slayer; but while it will do more damage to magic-imbued flesh than an ordinary sword would, it doesn’t wield itself –her actual sword skills are her own.) In a series, the key ingredient is a character(s) the reader likes enough to want to spend continuing time with. For me, Kate fits that bill. To be sure, she’s a rough-edged woman, something of a loner with authority issues and a tendency to be smart-mouthed; and while she’s not coarse, her vocabulary includes some pretty bad language at times. But for all that, she’s an intensely ethical person with a rock solid code of honor; if she needed to lay down her life to save a friend, or innocent people she doesn’t even know, she’d do it in a heartbeat, without whining or batting an eye (and she demonstrates that willingness here more than once). Though she doesn’t wear it on her sleeve, she also has a very real spirituality that might surprise some readers, and she’s not into casual sex. Like all of us, she’s a work under construction (and she grows some here).

Kate’s not the only well-drawn character here; the supporting cast, including a radically evil villain, are also vividly realized, with both virtues and foibles. (Were-lion Curran, Atlanta’s Beast Lord of the shapeshifters, for instance, is unquestionably a brave man and one with a deep sense of duty and responsibility to his Pack –but he’s also arrogant, and misguidedly convinced that he’s Nature’s gift to women.) The authors’ originality doesn’t end with the Shift; the factional landscape of their richly-drawn world includes a number of unique and intriguing features, like an unusual take on vampires –here, they’re mindless automatons, mentally dominated by a faction of mysterious and sinister necromancers.

In some ways, the plot is reminiscent of the old pulp noir detective novels, with magic instead of tommy guns and supernatural creatures instead of rival Mafia mobs, and a protagonist who could give Sam Spade as good as she got in wisecracks (but who’s got better morals and a kinder heart than he did) and has about the same philosophy of investigation: “Annoy the people involved until the guilty party tries to make you go away.” But it’s an exciting plot, with developments I genuinely didn’t expect. (One or two points don’t stand examination in hindsight very well, but the narrative flow is strong enough to mask that.) There’s also a very strong, well-done conflict of good vs. evil theme here.

In places, this book can have a deeply dark tone, in that no punches are pulled in describing the horrible cruelty that evil minds can inflict on their fellow beings; some of this can be graphic. It’s also a very violent tale, and some of the violence can be gory (one character, for instance, dies with her torso split open and her heart crushed in her opponent’s fist) but it’s not gratuitous and the authors don’t wallow in it. In its darker elements, the novel reflects the real world. But it also takes seriously the light that really exists in the darkness.

More than one male character is sexually interested in Kate; and precisely because she’s not free with her favors, those who see their masculinity as depending on sexual conquests clearly view her as a challenge in that area. But that’s just a realistically-depicted aspect of gender relations in a toxic culture; there isn’t any development of a relationship here (let alone a focus on it) that would put this tale in the area of ” paranormal romance.” (Though I understand that in the later books, Kate will find a love interest.) Readers should be aware that there’s a significant amount of bad language in the book, including a number of uses of the f-word. But although there are some occasional off-color wisecracks, there’s no sex here.

Finally, the edition I read has some special added features: FAQs, character profiles of Kate and a few others, and a description of the various “factions” in her Atlanta, all of which I read; a couple of scenes written from Curran’s viewpoint, which I skimmed, and which would be of most interest to die-hard series junkies; a “Factions Quiz” that I skipped, and an excellent prequel story, “A Questionable Client.” (One of the more unique characters in the novel is Saiman, and we’re told that Kate met him some time before when she took a gig as his bodyguard, and saved him from a murder attempt; here, we get to experience that particular episode.)

Author: Ilona Andrews

Publisher: Penguin Group, available through Amazon, both for Kindle and as a printed book.

A version of this review previously appeared on Goodreads.

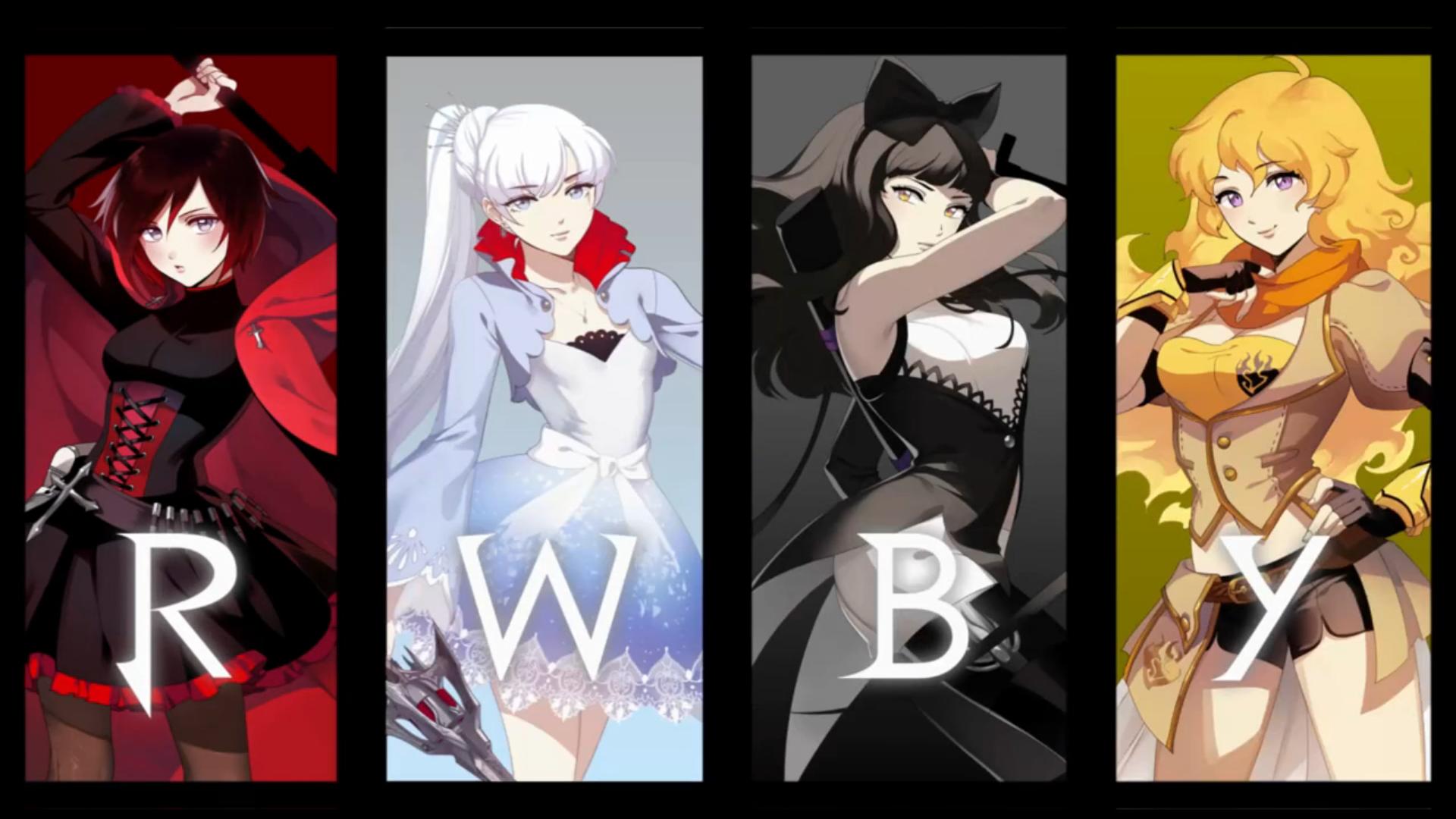

There are occasionally times where our book reviewer Werner’s “split scale” of grades for both artistic merit and action, would come in handy. This is one of those times. For the action scenes here are as glorious as you would expect from the man behind Dead Fantasy, virtuoso symphonies of exquisite hyper-violence, meted out and absorbed by characters and monsters without fear or bias, in ways limited only – and not very much, at that – by the creator’s imagination. Probably inevitably, this overshadows a fairly perfunctory plot, and characters whose characterization is largely defined by the shade they wear. On a split scale, this would merit five stars for both the quantity and quality of action, but likely three or three and a half for artistic merit.

There are occasionally times where our book reviewer Werner’s “split scale” of grades for both artistic merit and action, would come in handy. This is one of those times. For the action scenes here are as glorious as you would expect from the man behind Dead Fantasy, virtuoso symphonies of exquisite hyper-violence, meted out and absorbed by characters and monsters without fear or bias, in ways limited only – and not very much, at that – by the creator’s imagination. Probably inevitably, this overshadows a fairly perfunctory plot, and characters whose characterization is largely defined by the shade they wear. On a split scale, this would merit five stars for both the quantity and quality of action, but likely three or three and a half for artistic merit.