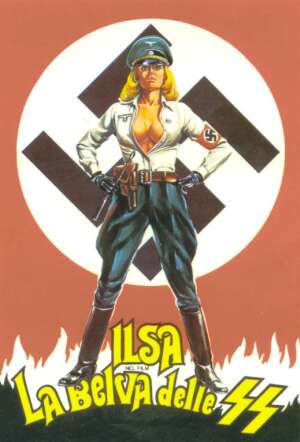

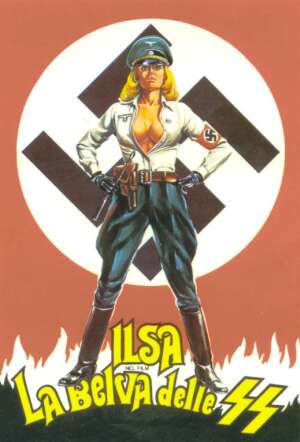

The late seventies was something of a golden era for exploitation, but few films have sustained their notoriety as well as the Ilsa series. Even more than forty years after the release of the first film starring Dyanne Thorne, there’s still something repellent and uncomfortable about the whole concept. Which is, of course, part of its transgressive appeal. Safe to say that the four films, made between 1975 and 1977 represent perhaps the most politically incorrect franchise ever to receive a theatrical release. Join with us, why don’t you, as we explore the mad, sick and twisted world of Ilsa, beginning with what still remains today, one of the most notorious grindhouse films ever made.

Ilsa, She-Wolf of the S.S.

★★★★

I used to have an Ilsa, She-wolf of the SS T-shirt, but only ever dared wear it once in public – the looks of hate it provoked were simply too much to bear, though I don’t exactly kowtow to moral pressure or political correctness easily. And when I bought the DVD in the Hollywood Virgin Megastore, a complete stranger standing next to me commented to the effect that this wasn’t the sort of thing we needed to see getting re-released. Such is the power of Ilsa.

I used to have an Ilsa, She-wolf of the SS T-shirt, but only ever dared wear it once in public – the looks of hate it provoked were simply too much to bear, though I don’t exactly kowtow to moral pressure or political correctness easily. And when I bought the DVD in the Hollywood Virgin Megastore, a complete stranger standing next to me commented to the effect that this wasn’t the sort of thing we needed to see getting re-released. Such is the power of Ilsa.

Hence, I write with trepidation: even in the sordid yet enchanting world of exploitation cinema, She-Wolf is notorious. Three decades after being made, it remains unreleased – and possibly unreleasable – in the United Kingdom, and in our house, the DVD sat on the shelf for two years, since I feared Chris would instantly leave me if we watched it. And she is no shrinking violet, but a woman who (to my ultimate delight) regards an uncut DVD of The Story of Ricky as a fine birthday present. Luckily, Chris is right beside me as I type this, and I get to produce this article as a married, rather than divorced man.

I should point out, before the inevitable accusations come in, that the mark awarded to the film is scored on a radically different scale from “normal” movies. I don’t recommend this movie unless you possess a very black sense of humour, are immune to being offended by fictional material, have carefully stowed all children and maiden aunts, and switched off all moral qualms.

I should point out, before the inevitable accusations come in, that the mark awarded to the film is scored on a radically different scale from “normal” movies. I don’t recommend this movie unless you possess a very black sense of humour, are immune to being offended by fictional material, have carefully stowed all children and maiden aunts, and switched off all moral qualms.

Even so, the question must still be asked, is a Nazi camp a suitable setting for any piece of entertainment? No, probably not. But tell that to the producers of Hogan’s Heroes, a comedy set in a similar location. [Indeed, She-Wolf was filmed on Hogan’s sets, and the private life of star Bob Crane, was no less sordid than most exploitation films – as shown in Paul Schrader’s Auto Focus, which would make a fine double-bill with She-Wolf]. Or perhaps Schindler’s List, which in my opinion is more guilty of exploiting the Holocaust (interestingly, She-Wolf never mentions the J-word – it’s just a natural reaction these days to equate Nazi camps with Jews).

If I may digress for a moment, I find List a truly cynical work: Steven Spielberg performs his usual adept emotional manipulation, but what purpose is served? Like all docudramas, it alters the facts, and no Aryan Nation adherent will sit through a three-hour plus, black and white film for “educational” reasons. It seems more like a cynical, and successful, attempt to win Spielberg an Academy Award. Ask yourself an awkward question: would it have won seven Oscars if it had been about gypsies?

Like Schindler, the cinematic Ilsa was based on a real character. Ilsa Koch was the “Bitch of Buchenwald,” whose practices perhaps surpassed those in the movie, including the stripping and curing of human skin – particularly from tattoed inmates – for her collection of lampshades, gloves, etc. Unlike her fictional counterpart, she survived the war, being sentenced to live in prison, but sadly, didn’t live to see a twisted depiction of her life, committing suicide in 1967.

At least She-Wolf is upfront about its exploitational nature, despite an opening title which reads, in part, “We dedicate this film with the hope that these heinous crimes will never occur again.” This is such an implausible claim, you can’t even begin to take it seriously, especially when the next scene shows Ilsa (Dyanne Thorne) writhing atop one of the camp’s inmates. We don’t initially ‘know’ it’s her (though I doubt anyone is fooled!), until she returns, dressed as the commandant of Medical Camp 9.

It’s not long before her true persona is revealed, as she castrates her lover, fulfilling in a twisted way her promise that he wouldn’t return to the camp. The arrival at camp of a new batch of inmates allows the depiction of a whole new range of potential tortures, even if there is a surprising amount of plot going on too:

It’s not long before her true persona is revealed, as she castrates her lover, fulfilling in a twisted way her promise that he wouldn’t return to the camp. The arrival at camp of a new batch of inmates allows the depiction of a whole new range of potential tortures, even if there is a surprising amount of plot going on too:

- Ilsa’s attempts to prove women are better than men at handling pain…

- Her growing infatuation with American prisoner Wolfe (Gregory Knoph)…

- The prisoners’ plans to revolt…

- The imminent arrival of a General on a tour of inspection…

- The equally imminent arrival of Allied forces.

Though, being honest, these are secondary to the depiction of a huge range of sadistic and/or fetishistic practices. Floggings, electric dildos, decompression, surgery, golden showers, bondage – it’s all here, as well as good old-fashioned sexuality, making this truly a film with something for everyone. This is part of what makes for such uncomfortable viewing, it mixes the repellent and the fascinating unlike any other movie ever made – the closest I can think of would be Pasolini’s Salo, but that is Art, and consequently extremely tedious. That’s something you can certainly not say about Ilsa, where every few minutes brings some new unpleasantness to contemplate.

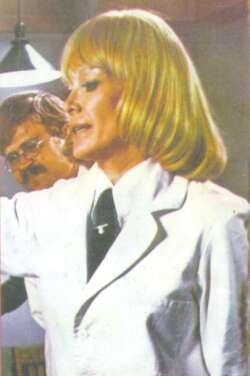

The “fascinating” would be Dyanne Thorne, whose portrayal is spot on, and without which the film would be no more than a parade of atrocities. She was already in her 40’s when it was made, and it’s rare, even nowadays, for a female character of that age to be shown with such unfettered sexuality. Admittedly, Thorne’s German accent is awful (she can’t even pronounce “Reich” correctly), but it’s a captivating and iconic performance of charisma and amorality.

It’s difficult to criticize the rest of the participants, since an awful lot of them seem to have suspiciously short filmographies, and I suspect pseudonyms were being used e.g. writer “Jonah Royston”, lead actor “Gregory Knoph” and, of course, producer “Herman Traeger” was in reality Dave Friedman, who worked with Herschell Gordon Lewis on the likes of Blood Feast and 2000 Maniacs. The only notable name, save an uncredited Uschi Digard, is Maria Marx, playing Anna, the prisoner whom even Ilsa cannot break – ironically Marx’s parents left Germany as refugees from Hitler. She was married to Melvin Van Peebles and is Mario’s mother.

Technically, it’s several steps better than you might think; there’s nothing complex or innovative, admittedly, but simply being coherent and in-focus puts it several levels above many video nasties, most of which are lamentably inept. Joe Blasco’s make-up effects hit the mark with disturbing frequency, though perhaps the most memorable moments are those which go beyond simple gore. For example, the dinner party entertainment, consisting of a naked woman suspended by piano wire, with her only support a steadily melting block of ice. This kind of stuff is simply wrong, yet I’ve little doubt worse things went on. [But for the most stomach-churning WW2 atrocity film, see Men Behind the Sun, covering the Japanese occupation of China and their human experiments]

Technically, it’s several steps better than you might think; there’s nothing complex or innovative, admittedly, but simply being coherent and in-focus puts it several levels above many video nasties, most of which are lamentably inept. Joe Blasco’s make-up effects hit the mark with disturbing frequency, though perhaps the most memorable moments are those which go beyond simple gore. For example, the dinner party entertainment, consisting of a naked woman suspended by piano wire, with her only support a steadily melting block of ice. This kind of stuff is simply wrong, yet I’ve little doubt worse things went on. [But for the most stomach-churning WW2 atrocity film, see Men Behind the Sun, covering the Japanese occupation of China and their human experiments]

While Ilsa wasn’t the first “video Nazi” (Love Camp 7 in 1967 predates it), it is certainly the most infamous, and is perhaps exploitation cinema in its most elemental form, going places where ordinary films would never dare to tread. Others among the most notorious films of the 1970’s have now been accepted into society (Texas Chainsaw Massacre, for example, now gets shown on British network TV), Ilsa still remains a pariah. If you have any interest in “polite society”, merely having the film on your shelf is an act of some courage – though any acknowledgement of its power and qualities, as here, does perhaps count as reckless. :-)

Ilsa is the antithesis of the word “heroine”, yet is undeniably a strong, independent female character (albeit one which proves that such traits are not necessarily a good thing), and on that ground alone, deserves recognition. There’s something almost rabidly feminist about her assertions of the superiority of women, and she is certainly a candidate for the most warped, despicable, relentlessly evil female character in cinema history. At the very least, the films remind us of the fragility of history: had things been only a little different, we could be living in a society where Ilsa was the heroine…

Dir: Don Edmonds

Star: Dyanne Thorne, Gregory Knoph, Tony Mumolo, Maria Marx

[I acknowledge the invaluable contribution of The Ilsa Chronicles, by Darren Venticinque and Tristan Thompson, published by Midnight Media, without which this article would be very plain in appearance!]

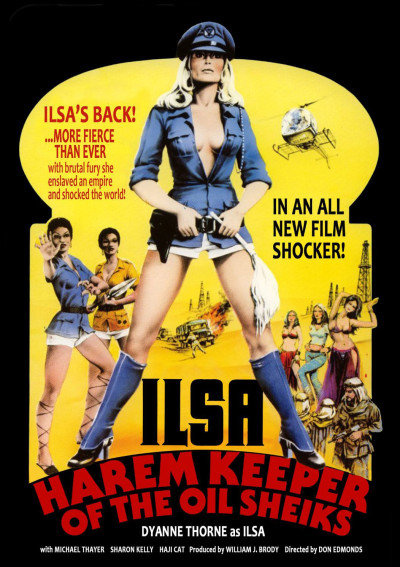

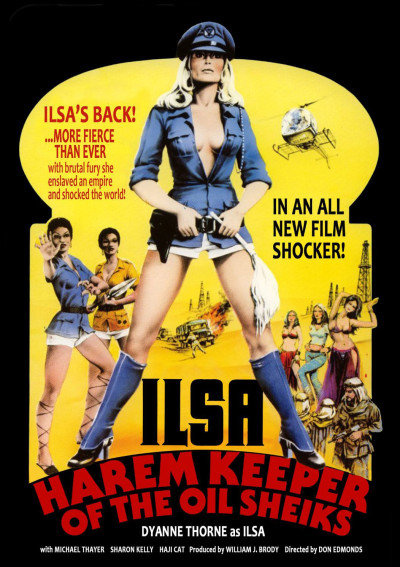

Ilsa, Harem Keeper of the Oil Sheiks

★★★

The success – or notoriety – of She-Wolf inevitably led to a sequel. riding roughshod over trivial issues like Ilsa having been killed at the end. Nor does anyone pay the slightest heed to thirty years having passed since the end of World War II, without her having apparently aged a day. That’s exploitation, folks! For this takes place in the modern era, with the Middle East replacing Germany, as the title suggests. Ilsa is now the right-hand woman of El Sharif (Alexander, a pseudonym for Jerry Delony), whose duties mostly involve keeping him supplied with a steady supply of more or less pliable Western woman for his sexual needs. Some discretion becomes necessary, due to the arrival of American businessman and thinly-disguised Dr. Kissinger lookalike, Dr. Kaiser (Roehm, a pseudonym for Richard Kennedy) and his “aide” Adam Scott (Thayer, a pseudonym – as in the original, you’ll be detecting a theme here – for Max Thayer), who is actually a CIA agent. Bedding Ilsa, he turns her against El Sharif, and when she is punished for her disloyalty, she switches sides entirely, supporting the nephew and assisting in a palace coup aimed at overthrowing her former employer.

The success – or notoriety – of She-Wolf inevitably led to a sequel. riding roughshod over trivial issues like Ilsa having been killed at the end. Nor does anyone pay the slightest heed to thirty years having passed since the end of World War II, without her having apparently aged a day. That’s exploitation, folks! For this takes place in the modern era, with the Middle East replacing Germany, as the title suggests. Ilsa is now the right-hand woman of El Sharif (Alexander, a pseudonym for Jerry Delony), whose duties mostly involve keeping him supplied with a steady supply of more or less pliable Western woman for his sexual needs. Some discretion becomes necessary, due to the arrival of American businessman and thinly-disguised Dr. Kissinger lookalike, Dr. Kaiser (Roehm, a pseudonym for Richard Kennedy) and his “aide” Adam Scott (Thayer, a pseudonym – as in the original, you’ll be detecting a theme here – for Max Thayer), who is actually a CIA agent. Bedding Ilsa, he turns her against El Sharif, and when she is punished for her disloyalty, she switches sides entirely, supporting the nephew and assisting in a palace coup aimed at overthrowing her former employer.

If not quite in as spectacularly poor taste as the original, it certainly isn’t going to be mistaken for a Disney movie, with exploding IUDs, forced plastic surgery, burning alive, any amount of more mundane tortures and soft(ish)-core sex, plus copious amounts of gratuitous nudity from just about every female in the cast. Those include the return of Russ Meyer favourite Uschi Digard, who gets a larger role than in the first film, and also Haji from Faster Pussycat, who plays an undercover asset for Scott, whose mission is discovered by Ilsa. Having a tape-recorder that looks about the size of a briefcase was probably, in hindsight, a bad move… Outside of Ilsa, however, the two most memorable are Ilsa’s sidekicks, Satin and Velvet (Tanya Boyd and Marilyn Joy – the latter would play Cleopatra Schwarz in The Kentucky Fried Movie the following year), who appear inspired by Bambi and Thumper in Diamonds are Forever. They kick ass, not least while topless and oiled, ripping off the testicles of one delinquent soldier with their bare hands, so he can be added to Ilsa’s stable of eunuchs. That’s an incentive policy I hope my workplace doesn’t adopt.

It’s significantly slicker than She-Wolf, with considerably better production values, but that isn’t unequivocally a good thing for the grindhouse genre, since it’s the rough edges which tend to make for the most memorable entries. You get the sense here the makers were more self-consciously going for the shock and outrage, rather than them stemming organically from the setting, and their deliberate nature makes them less effective. I was also disappointed in how Ilsa suddenly switched into acting like a love-struck schoolgirl at the drop of one good bedding at the hands (or whatever) of Adam: that isn’t the villainess for which I signed up. Still, it is kinda nice to reach the end and not feel that you need a shower, with the camp elements here helping to lighten the tone, and providing a welcome reminder than none of this should be taken in the slightest bit seriously.

Dir: Don Edmonds

Star: Dyanne Thorne, Michael Thayer, Victor Alexander, Wolfgang Roehm

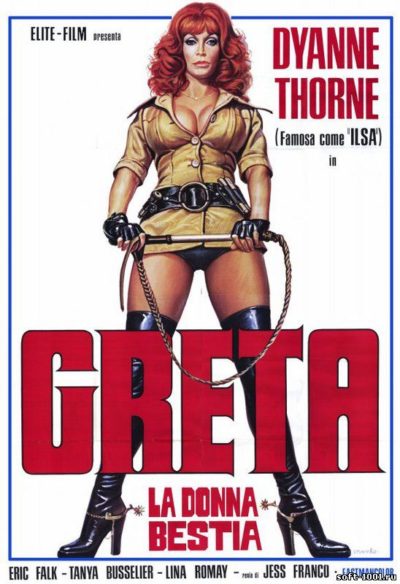

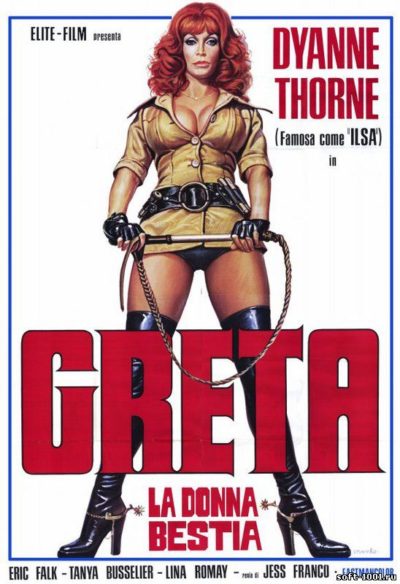

Ilsa, the Wicked Warden

★½

Director Jess Franco has something of a cult following, which I never understood. Sure, there are worse directors out there, but there aren’t many duller ones. I had the misfortune to watch two of his films this week: the other was his Count Dracula, and managed to be coma-inducingly tedious, despite haviing Christopher Lee and Klaus Kinski, two actors I would watch recite the telephone directory. This “bootleg Ilsa” entry is perhaps even worse. It wasn’t originally intended as part of the series – a big giveaway is that Dyanne Thorne’s character isn’t even blonde – but at some point ended up re-titled and redubbed to turn the originally-named “Greta” into “Ilsa”. To avoid any additional confusion, the latter is how I’ll refer to her.

Director Jess Franco has something of a cult following, which I never understood. Sure, there are worse directors out there, but there aren’t many duller ones. I had the misfortune to watch two of his films this week: the other was his Count Dracula, and managed to be coma-inducingly tedious, despite haviing Christopher Lee and Klaus Kinski, two actors I would watch recite the telephone directory. This “bootleg Ilsa” entry is perhaps even worse. It wasn’t originally intended as part of the series – a big giveaway is that Dyanne Thorne’s character isn’t even blonde – but at some point ended up re-titled and redubbed to turn the originally-named “Greta” into “Ilsa”. To avoid any additional confusion, the latter is how I’ll refer to her.

It’s certainly not far from the other entries in tone or content. Ilsa (Thorne) runs a lunatic asylum, Las Palomas Clinic, in the South American jungle, that specializes in young women with sexual issues such as nymphomania or lesbianism (in other words, the photogenic ones!). When one escapes, making it to the house of Dr. Arcos (Franco) before being recaptured and vanishing, the good doctor raises concerns. He’s approached by her sister, Abby Phillips (Bussellier), and agrees to have her committed to the asylum under an assumed name, so she can find out what’s going on. Turns out the place is also being used as a black site for political dissidents, with Ilsa also running a side-line of pornographic films starring the inmates. Discovering this will require Abby to get through not just Ilsa, but also Juana (Romay), the top dog at the facility, who abuses her position ever bit as much.

This is mind numbingly dull, with a capital D, despite an almost constant parade of female nudity – the clinic appears to suffer from a shocking lack of underwear. While the other entries in the series are fairly equal-opportunity in their viciousness, with both sexes falling foul of Ilsa’s sadism, this frequently descends into fully-fledged misogyny – even if the perpetrators are often women too. If you make it all the way through, you’ll likely need a shower, though it’s more probably your interest will have made an exit before that becomes necessary. It doesn’t even have the grace to focus on Ilsa, with Abby being the central character for much of it. About the only section likely to stick in your mind is the very end – again, if you haven’t found anything better to do – where Franco suddenly decides he’s making the world’s first cannibal women-in-prison film.

Not helped by a dub that appears to be English as a second language, containing made-up words such as “provocate,” this solidifies Franco’s position as among the least talented directors in cinema history. Despite having already helmed over 80 movies by this point in his career, there’s no indication he had learned anything from the experience, delivering a feature-film which all but entirely squanders its main asset, Thorne’s charisma. Nice though it would be to claim the political angle was subtle satire regarding life in post-Franco Spain, that would seem a real stretch. If I never have to sit through two of his movies in the same week again, it will be too soon.

Dir: Jess Franco

Star: Tania Busselier, Dyanne Thorne, Lina Romay, Jess Franco

a.k.a. Greta: Haus Ohne Männer; Greta, the Mad Butcher; Ilsa: Absolute Power; Wanda, the Wicked Warden

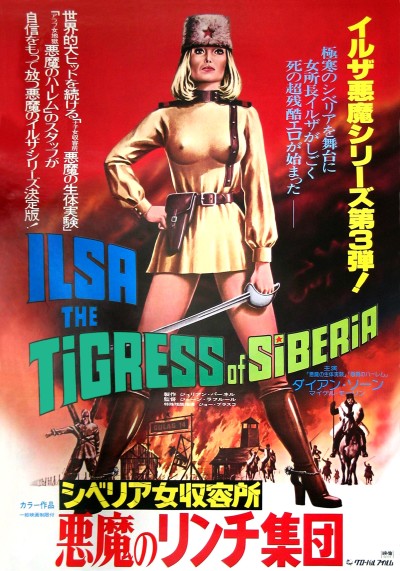

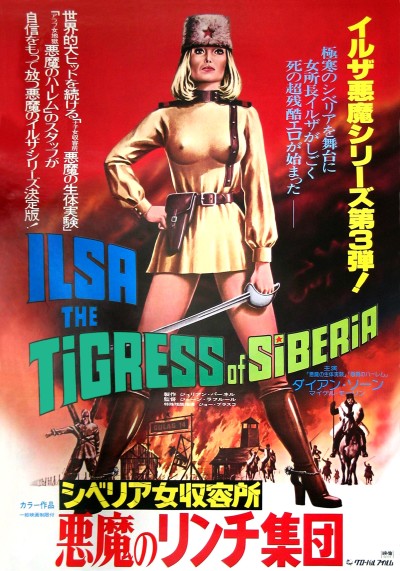

Ilsa, the Tigress of Siberia

★★½

If the second film showcased Ilsa’s apparently miraculous immortality, the fourth and final is even more implausible, taking place both in 1953 Soviet Russia, and 1977 Montreal, with Thorne looking more or less identical in both, save for a change in hairstyle. It begins in a gulag, where Ilsa has found a new use for her sadistic talents overseeing a Siberian prison, the Soviets presumably being willing to overlook that whole pesky “Nazi war criminal” thing. There, she has clearly not mellowed, spearing an escaped prisoner, and ensuring he’s dead by having his head smashed with an enormous mallet. Oh, and the name “Tigress” isn’t just a sobriquet, given she keeps one of them in a pit. The new arrivals include political dissident Andrei Chikurin, (Morin), whom she vows to break, and the son of a Politburo member, imprisoned for drunken hooliganism. When the regime in Moscow changes after Stalin’s death, Ilsa swiftly packs up shop: as with her Nazi camp, the aim is to dispose of all the prisoners and leave no witnesses, but Chikurin survives.

If the second film showcased Ilsa’s apparently miraculous immortality, the fourth and final is even more implausible, taking place both in 1953 Soviet Russia, and 1977 Montreal, with Thorne looking more or less identical in both, save for a change in hairstyle. It begins in a gulag, where Ilsa has found a new use for her sadistic talents overseeing a Siberian prison, the Soviets presumably being willing to overlook that whole pesky “Nazi war criminal” thing. There, she has clearly not mellowed, spearing an escaped prisoner, and ensuring he’s dead by having his head smashed with an enormous mallet. Oh, and the name “Tigress” isn’t just a sobriquet, given she keeps one of them in a pit. The new arrivals include political dissident Andrei Chikurin, (Morin), whom she vows to break, and the son of a Politburo member, imprisoned for drunken hooliganism. When the regime in Moscow changes after Stalin’s death, Ilsa swiftly packs up shop: as with her Nazi camp, the aim is to dispose of all the prisoners and leave no witnesses, but Chikurin survives.

24 years later, he’s part of a hockey team playing games in Canada, and goes to a whorehouse with some team-mates, completely unaware that it’s run by Ilsa, who now has a new line in mind-control technology, which she uses both on her hookers and rival gangsters, to cement her position. She’s startled to see him and, concerned he’s out for revenge, kidnaps Chikurin. However, that backfires, as it brings her back to the attention of the Soviets – not least the Politburo members who still holds a grudge against her for the death of her son, and who sets the local office of the KGB on her tail. Which makes this an extremely rare case of a North American movie from the time where the KGB are not the bad guys. It’s also worth noting that even the mind-control aspects are not that far-fetched, since the CIA’s infamous Project MKUltra had a Montreal outpost from 1957 to 1964 at McGill University, information revealed a couple of years prior to Tigress‘s 1977 release.

The first half does ramp up the violence at the cost of the sex, mostly because Ilsa is close to being the only woman in the gulag. But the second half flips that around, as we get into the prostitution ring, and to be honest, given the amount of time devoted to them, the film would be more accurately titled Ilsa, Madam of Montreal. And that’s a bit of a shame, because it’s probably the stuff in the frozen wastes of Siberia that are more interesting than a prosaic and forgettable crime story, which is what the second half collapses into. Even Ilsa seems to be a kinder, gentler model; I can only blame Canada for this disappointing softness. There is some ironic appropriateness to the ending, which sees Ilsa stuck in the middle of a frozen lake, burning her money to try and stay warm. Though compared to the fate which befell many of those who cross their path, this is certainly weak sauce as well. It’s a shame they did not apparently proceed with an entire film based in Siberia, as what results instead is little more than half a true Ilsa film.

Dir: Jean LaFleur

Star: Dyanne Thorne, Michel Morin, Tony Angelo, Terry Coady

There are elements here which reminded me of Children of Men, though this is set further down the road, when civilization has decayed a good deal further. The issue here is slightly different: specifically, a lack of female children, which has triggered a rapid collapse into anarchy for the United States. 25 years later, the National Obstetric Alliance (NOA) seek far and wide for young girls, who are brought to their compound in the Pacific Northwest, to be held until the age of 21 when… Well, their fate gets a bit murky. Approaching that point is Zoey, who has known almost no other life. But after she’s subjected to a harrowing bout of psychological torture in a sensory-deprivation chamber called “the box”, her whole attitude changes, and she’s prepared to go to any lengths to escape, and take the other women with her.

There are elements here which reminded me of Children of Men, though this is set further down the road, when civilization has decayed a good deal further. The issue here is slightly different: specifically, a lack of female children, which has triggered a rapid collapse into anarchy for the United States. 25 years later, the National Obstetric Alliance (NOA) seek far and wide for young girls, who are brought to their compound in the Pacific Northwest, to be held until the age of 21 when… Well, their fate gets a bit murky. Approaching that point is Zoey, who has known almost no other life. But after she’s subjected to a harrowing bout of psychological torture in a sensory-deprivation chamber called “the box”, her whole attitude changes, and she’s prepared to go to any lengths to escape, and take the other women with her.

Stealing from both Open Water and

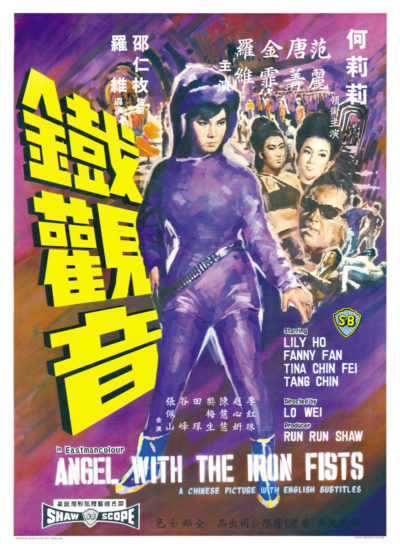

Stealing from both Open Water and  Swinging wildly between the surprisingly smart and the brain-numbingly stupid, this 1967 Hong Kong film is, in the end, not much more than a bad James Bond knock-off, despite its female lead. The heroine, Luo Na (Ho), is unsubtly named Agent 009, and goes to Hong Kong, posing as the mistress of an imprisoned gangster, who supposedly knows where he hid his ill-gotten gains. This brings her to the attention of the Dark Angels, whose leader is played by Tina Chin-Fei. This is a surprisingly gynocentric organization, owning both a vast, sprawling, underground lair and fetching two-piece uniforms. Keen to find out what Lona knows, they recruit her – which was 009’s cunning plan all along.

Swinging wildly between the surprisingly smart and the brain-numbingly stupid, this 1967 Hong Kong film is, in the end, not much more than a bad James Bond knock-off, despite its female lead. The heroine, Luo Na (Ho), is unsubtly named Agent 009, and goes to Hong Kong, posing as the mistress of an imprisoned gangster, who supposedly knows where he hid his ill-gotten gains. This brings her to the attention of the Dark Angels, whose leader is played by Tina Chin-Fei. This is a surprisingly gynocentric organization, owning both a vast, sprawling, underground lair and fetching two-piece uniforms. Keen to find out what Lona knows, they recruit her – which was 009’s cunning plan all along.

I used to have an Ilsa, She-wolf of the SS T-shirt, but only ever dared wear it once in public – the looks of hate it provoked were simply too much to bear, though I don’t exactly kowtow to moral pressure or political correctness easily. And when I bought the DVD in the Hollywood Virgin Megastore, a complete stranger standing next to me commented to the effect that this wasn’t the sort of thing we needed to see getting re-released. Such is the power of Ilsa.

I used to have an Ilsa, She-wolf of the SS T-shirt, but only ever dared wear it once in public – the looks of hate it provoked were simply too much to bear, though I don’t exactly kowtow to moral pressure or political correctness easily. And when I bought the DVD in the Hollywood Virgin Megastore, a complete stranger standing next to me commented to the effect that this wasn’t the sort of thing we needed to see getting re-released. Such is the power of Ilsa. I should point out, before the inevitable accusations come in, that the mark awarded to the film is scored on a radically different scale from “normal” movies. I don’t recommend this movie unless you possess a

I should point out, before the inevitable accusations come in, that the mark awarded to the film is scored on a radically different scale from “normal” movies. I don’t recommend this movie unless you possess a  It’s not long before her true persona is revealed, as she castrates her lover, fulfilling in a twisted way her promise that he wouldn’t return to the camp. The arrival at camp of a new batch of inmates allows the depiction of a whole new range of potential tortures, even if there is a surprising amount of plot going on too:

It’s not long before her true persona is revealed, as she castrates her lover, fulfilling in a twisted way her promise that he wouldn’t return to the camp. The arrival at camp of a new batch of inmates allows the depiction of a whole new range of potential tortures, even if there is a surprising amount of plot going on too: Technically, it’s several steps better than you might think; there’s nothing complex or innovative, admittedly, but simply being coherent and in-focus puts it several levels above many video nasties, most of which are lamentably inept. Joe Blasco’s make-up effects hit the mark with disturbing frequency, though perhaps the most memorable moments are those which go beyond simple gore. For example, the dinner party entertainment, consisting of a naked woman suspended by piano wire, with her only support a steadily melting block of ice. This kind of stuff is simply

Technically, it’s several steps better than you might think; there’s nothing complex or innovative, admittedly, but simply being coherent and in-focus puts it several levels above many video nasties, most of which are lamentably inept. Joe Blasco’s make-up effects hit the mark with disturbing frequency, though perhaps the most memorable moments are those which go beyond simple gore. For example, the dinner party entertainment, consisting of a naked woman suspended by piano wire, with her only support a steadily melting block of ice. This kind of stuff is simply

Director Jess Franco has something of a cult following, which I never understood. Sure, there are worse directors out there, but there aren’t many

Director Jess Franco has something of a cult following, which I never understood. Sure, there are worse directors out there, but there aren’t many

You could call this a foul-mouthed, borderline misogynist, zero budget piece of trash, with no coherent plot, where it seems every other word is a F-bomb or C-missile, and most of the lines are not so much spoken, as yelled. I wouldn’t argue with such an assessment, and understand perfectly why it is rated 1.4 on IMDb. And, yet… It has a relentless and manic energy which makes Crank look like a Merchant-Ivory costume drama. Put another way: unlike the overlong Rogue One, I did not fall asleep here, and it will likely stick in my mind longer than the three other, far more polished productions, which I watched the same day. Probably because, unlike this, they did not have a topless little person being tossed off a roof.

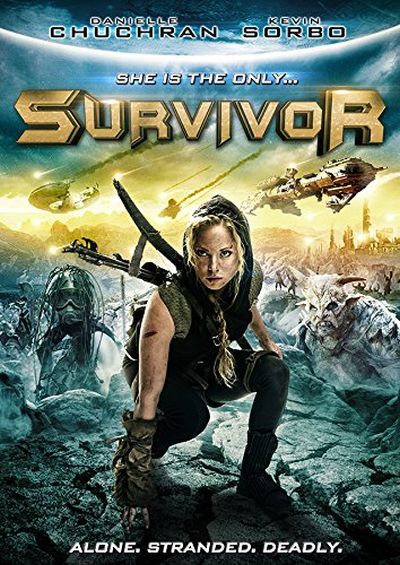

You could call this a foul-mouthed, borderline misogynist, zero budget piece of trash, with no coherent plot, where it seems every other word is a F-bomb or C-missile, and most of the lines are not so much spoken, as yelled. I wouldn’t argue with such an assessment, and understand perfectly why it is rated 1.4 on IMDb. And, yet… It has a relentless and manic energy which makes Crank look like a Merchant-Ivory costume drama. Put another way: unlike the overlong Rogue One, I did not fall asleep here, and it will likely stick in my mind longer than the three other, far more polished productions, which I watched the same day. Probably because, unlike this, they did not have a topless little person being tossed off a roof. Arrowstorm Entertainment appear to have quietly become a minor creator of action heroine flicks. We’ve previously written about several entries in their

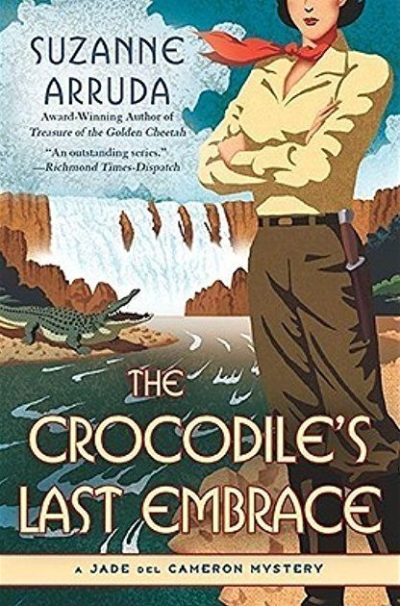

Arrowstorm Entertainment appear to have quietly become a minor creator of action heroine flicks. We’ve previously written about several entries in their  This sixth installment in Arruda’s outstanding series has much in common, in terms of style and other characteristics, with the preceding five. We pick up here in February 1921, and our setting is the familiar one of Nairobi and its environs; all or most of the supporting cast we’ve come to like are here, as well as Jade herself.

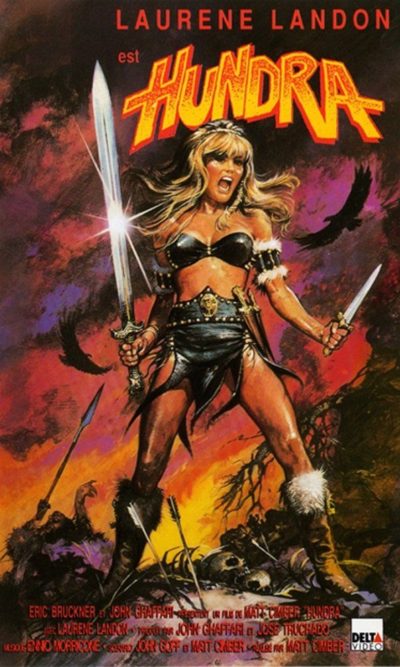

This sixth installment in Arruda’s outstanding series has much in common, in terms of style and other characteristics, with the preceding five. We pick up here in February 1921, and our setting is the familiar one of Nairobi and its environs; all or most of the supporting cast we’ve come to like are here, as well as Jade herself. Director Cimber seems always to have had an interest in the action-heroine genre, having previously directed Lady Cocoa, he’d go on to do Yellow Hair and the Fortress of Gold , also starring Landon, and work on Gorgeous Ladies of Wrestling. But this was likely his best work, a rather inspired Conan knock-off, which both predates and is significantly better than Red Sonja.

Director Cimber seems always to have had an interest in the action-heroine genre, having previously directed Lady Cocoa, he’d go on to do Yellow Hair and the Fortress of Gold , also starring Landon, and work on Gorgeous Ladies of Wrestling. But this was likely his best work, a rather inspired Conan knock-off, which both predates and is significantly better than Red Sonja.

I’m a big fan of any film with an outrageous premise, and this one certainly delivers. Mob hitman Frank Kitchen (Rodriguez) carries out his latest job with no qualms, killing a debtor. What he doesn’t realize is, the victim’s sister is a talented but EXTREMELY twisted surgeon, Dr. Rachel Jane (Weaver). She vows to take revenge on Frank by removing what she feels matters most to him: his masculinity. Kitchen is knocked out, kidnapped, and wakes up in a seedy hotel room, to find herself in possession of a couple of things she didn’t have before, and missing something she used to have. But gender reassignment does not make the (wo)man, and an extremely pissed-off Frank vows revenge of her own, both on Jane and Honest John Hartunian (LaPaglia), the former employer who betrayed Kitchen.

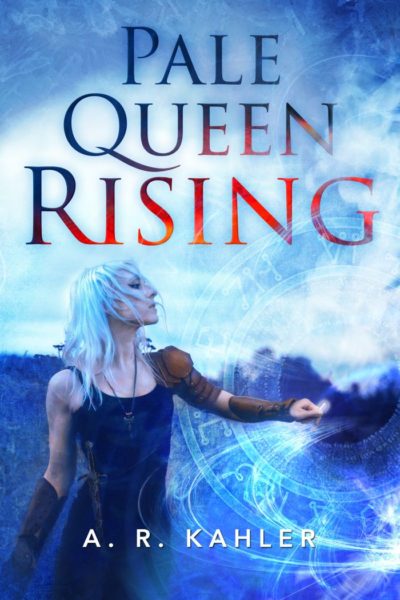

I’m a big fan of any film with an outrageous premise, and this one certainly delivers. Mob hitman Frank Kitchen (Rodriguez) carries out his latest job with no qualms, killing a debtor. What he doesn’t realize is, the victim’s sister is a talented but EXTREMELY twisted surgeon, Dr. Rachel Jane (Weaver). She vows to take revenge on Frank by removing what she feels matters most to him: his masculinity. Kitchen is knocked out, kidnapped, and wakes up in a seedy hotel room, to find herself in possession of a couple of things she didn’t have before, and missing something she used to have. But gender reassignment does not make the (wo)man, and an extremely pissed-off Frank vows revenge of her own, both on Jane and Honest John Hartunian (LaPaglia), the former employer who betrayed Kitchen. Claire is the official “court assassin” to Mab, who is the Winter Faerie Queen. Her realm lies in a world parallel to ours, but separate from it, and inhabited by a slew of creatures we humans know only from myth, who can travel back and forth to the mortal world. Mab traffics in “Dream”, which is somewhere between a food, a drug and currency for her citizens, and the product of human emotions, particularly in group settings such as concerts or other shows. However, someone is muscling in on her turf, with the intent of controlling the Dream, and she unleashes Claire to track down the culprit, who turns out to be the ‘Pale Queen’ of the title.

Claire is the official “court assassin” to Mab, who is the Winter Faerie Queen. Her realm lies in a world parallel to ours, but separate from it, and inhabited by a slew of creatures we humans know only from myth, who can travel back and forth to the mortal world. Mab traffics in “Dream”, which is somewhere between a food, a drug and currency for her citizens, and the product of human emotions, particularly in group settings such as concerts or other shows. However, someone is muscling in on her turf, with the intent of controlling the Dream, and she unleashes Claire to track down the culprit, who turns out to be the ‘Pale Queen’ of the title.