Literary rating: ★

Kick-butt quotient: ☆☆☆

Disclaimer at the outset: I haven’t read this novel from cover to cover. Seven years ago, I read the prologue and first three chapters; this time around, I read the first seven (re-reading the ones I’d read before), and skimmed the last ten and the epilogue –though I skimmed very thoroughly, taking about three hours and absorbing all of the major plot points. I feel qualified to give it a fair rating and review; but the level of bad language and grungy sexual content, blended with the tedious prose style and the wall-to-wall cynicism of the author’s literary vision (if we can call it that) made this too distasteful to read word-for-word any further.

Disclaimer at the outset: I haven’t read this novel from cover to cover. Seven years ago, I read the prologue and first three chapters; this time around, I read the first seven (re-reading the ones I’d read before), and skimmed the last ten and the epilogue –though I skimmed very thoroughly, taking about three hours and absorbing all of the major plot points. I feel qualified to give it a fair rating and review; but the level of bad language and grungy sexual content, blended with the tedious prose style and the wall-to-wall cynicism of the author’s literary vision (if we can call it that) made this too distasteful to read word-for-word any further.

Our title character here is Teresa Mendoza, who, when we first meet her, is a 22-year-old girl from Culiacan, Sinola, Mexico, a community dominated by the cross-border Mexican-U.S. drug traffic. Her boyfriend is a airplane pilot ferrying drugs for a local narco kingpin. But this boyfriend had a bad habit of defrauding his employer with side deals of his own and bragging about it when he was drunk; the prologue opens with her phone ringing to inform her that his boss has just had him killed –and that she’d better run, because the killers are on their way to dispatch her, too. Her resulting 13-year odyssey will take her to Spain (Perez-Reverte’s home country), see her eventually rise to control the drug traffic into and through southern Spain, and eventually bring her back full circle to the place of her birth and a reckoning with the past.

There’s a solid story here, which despite its seeming far-fetched improbability is plotted in a way that actually comes across as believable (except for Teresa settling and working in Spain under her real name, and not getting whacked within a matter of weeks!) and told with a few twists that I did not see coming, even though I’d skimmed the ending seven years earlier. The author appears to be extremely knowledgeable about the history and minutia of drug trafficking, at least up to 2002 when the novel was written (though he doesn’t quite understand that not all readers are necessarily as fascinated as he apparently is with every scrap of minutia). Teresa is a complex character, not one a reader will readily forget; and there are moments in the story that are quite emotionally evocative, even poignant.

However, the execution of the idea is wanting here, in several respects. First, Perez-Reverte gives us two interlaced narratives, Teresa’s own direct story in the third person and that of a journalist, in the first person, who’s piecing together her story from interviews with her (in the first chapter; most of the rest of her saga unfolds in flashback) and others who knew her. The actual meat of the story is in the former strand of narrative, however; the journalist’s really adds nothing except padding to bulk the book up to its 436 pages. There’s nothing of substance in his contribution that couldn’t have been conveyed much more economically, and with a more unified structure, by incorporating it into the third-person narrative. Every time we switch to his strand, there’s a marked loss of momentum and interest.

Even in the strand focused on Teresa directly, however, the prose is slow-moving, and detail heavy (about a third of the text could probably have been edited out without major damage, and it would have produced a quicker, more easily-flowing read). Given that it’s also peppered with constant f-words (probably incongruous for Spanish-language speakers) and other foul language and crude sexual content, both heterosexual and lesbian, for me it was a real chore to read as much as I did. Perez-Reverte (who’s the author of at least five other novels, though I haven’t read any of those) also affects a self-consciously “literary” style, with a lot of emphasis on his protagonist’s inner thoughts and on portentiously-described Significant Moments, which gets old quickly. In fairness to the author, the translator is probably responsible for the f-words and for the erroneous use of “clips” to describe ammunition magazines –and certainly for the frequent Spanish phrases left untranslated, apparently to give the text a Spanish flavor. (Most monolingual English-language readers would have preferred that he’d stuck to doing that with familiar words like “si” and “gracias,” that don’t need translation.)

For a writer who was so inclined, the subject matter here would be a gold mine for moral and social reflection. The storyline cries out for exploration of the (im)morality of a drug trade that corrupts and destroys every life it touches, of the roots of demand for drugs in modern society, of the inequities in Mexican government and society for which the drug trade is a symptom and a result, of the failure of the prison system as an instrument of rehabilitation or justice, and any number of other serious themes. Readers who bring the raw materials for such reflection with them to the book may indeed think about these things, but without any direct encouragement from the author. His basic message appears to be nihilistic cynicism; and if anything, he tends to glorify drug trafficking, in somewhat the same fashion as the “narcocorridos” that he quotes at times.

For a writer who was so inclined, the subject matter here would be a gold mine for moral and social reflection. The storyline cries out for exploration of the (im)morality of a drug trade that corrupts and destroys every life it touches, of the roots of demand for drugs in modern society, of the inequities in Mexican government and society for which the drug trade is a symptom and a result, of the failure of the prison system as an instrument of rehabilitation or justice, and any number of other serious themes. Readers who bring the raw materials for such reflection with them to the book may indeed think about these things, but without any direct encouragement from the author. His basic message appears to be nihilistic cynicism; and if anything, he tends to glorify drug trafficking, in somewhat the same fashion as the “narcocorridos” that he quotes at times.

To the extent that he has a vision, it could fairly be summarized as: “Wow, Teresa is a tough survivor who climbs to the top of the heap against odds; isn’t she COOL?” Well –no. She is a tough survivor who can handle threatening situations with courage and resolution; she has intelligence and talents that could be put to more constructive uses than they get, and she demonstrates some instinctive basic decency in her face-to-face relations with people. But she’s incapable (or doesn’t want to be capable) of any reflection about the consequences of her actions for people who use the drugs she transports, and doesn’t come across as particularly likable or admirable in most ways that count. (We’re also asked to believe –unrealistically– that her own drug habit has no more psychological or physical consequences than chewing gum would have; and some readers probably will believe it, to their own detriment.) I wouldn’t characterize her as an evil villainess –but I wouldn’t call her a heroine or a role model, either.

Readers who frequent this site will, understandably, be interested in the book’s action component. I set Teresa’s kick-butt quotient at three stars as a matter of attitude; she’s pragmatic about the elimination of enemies, though unlike the drug lords of Sinola, she’s not into slaughtering their innocent families. (She may threaten it for effect, but the reader knows that on that score, her bark is worse than her bite; and she’s capable of mercy where others in her position might not have shown it.) But as far as any direct personal action on her part goes, she picks up and uses a gun here exactly twice, once near the beginning and once in the climactic shoot-out near the end. And that scene is described, in Perez-Reverte’s typically “literary” fashion, in a sort of stream-of-consciousness style from a slightly befuddled viewpoint; he doesn’t handle the action with the clarity that some other writers would.

Author: Arturo Perez-Reverte

Publisher: Putnam, available through Amazon, both for Kindle and as a printed book.

This book wasn’t on my radar until a friend recommended it. But it proved to be well worth the read –and further demonstrates that there are independent authors out there producing quality work, and who aren’t getting the notice they ought to. J. C. Antonelli is one of these! Hopefully, this review will give you an idea of whether or not the book would be up your alley. If so, the novel has the added advantage of being a stand-alone; reading it won’t suck you into a long series.

This book wasn’t on my radar until a friend recommended it. But it proved to be well worth the read –and further demonstrates that there are independent authors out there producing quality work, and who aren’t getting the notice they ought to. J. C. Antonelli is one of these! Hopefully, this review will give you an idea of whether or not the book would be up your alley. If so, the novel has the added advantage of being a stand-alone; reading it won’t suck you into a long series.

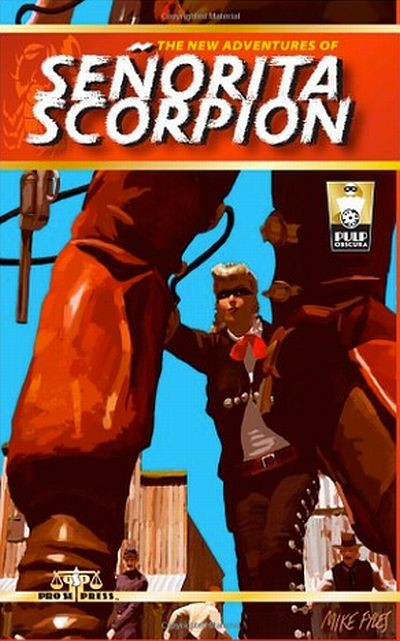

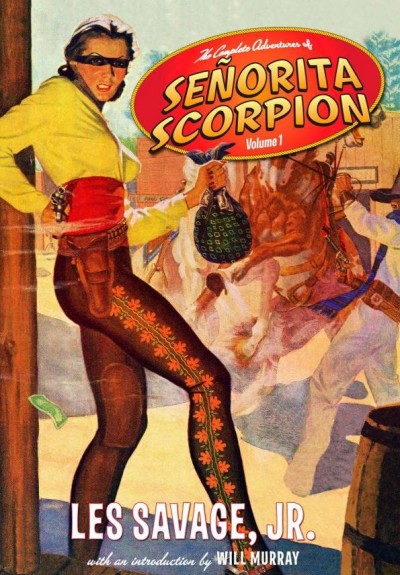

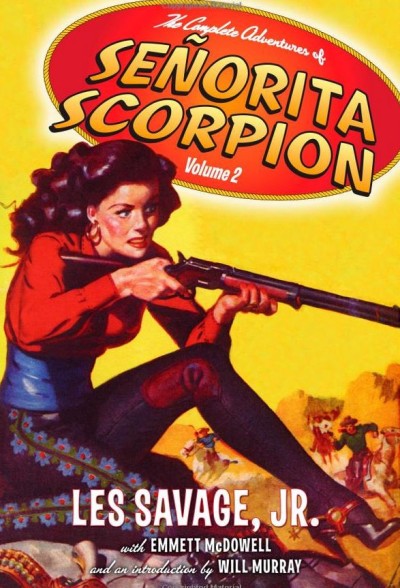

Action adventure fiction, in the pulp era, tended to be a male-dominated field; the writers and readers were overwhelmingly male, and the protagonists having the adventures and engaging in the derring-do tended to be correspondingly male. The culture of that day had deep-rooted stereotypes about the unfitness of the “weaker sex” for strenuous physical challenges, and about the inappropriateness of combat as a role for females who were supposed to be naturally gentle and demure. But there were writings that bucked these assumptions, particularly in the Western genre. Senorita Scorpion, the creation of Les Savage, Jr. (1922-1958), wasn’t actually the first pistol-packing cowgirl to be featured in the Western pulps of the 30s and 40s; but she proved to be the most popular, one of the most unique, and probably the subject of the longest running and thickest corpus of material of any of these fictional ladies: seven stories, originally published in Action Stories from 1944-49. Through its Altus Press imprint, (CreateSpace is just the printing service) Pro Se Press seeks to bring the best fiction of the early modern pulp magazine era back into print, in book form now, for a new generation of fans. These stories (plus one by Emmett McDowell, which used the Senorita Scorpion name for an entirely different character) were a felicitous choice for one of their first projects, in two volumes.

Action adventure fiction, in the pulp era, tended to be a male-dominated field; the writers and readers were overwhelmingly male, and the protagonists having the adventures and engaging in the derring-do tended to be correspondingly male. The culture of that day had deep-rooted stereotypes about the unfitness of the “weaker sex” for strenuous physical challenges, and about the inappropriateness of combat as a role for females who were supposed to be naturally gentle and demure. But there were writings that bucked these assumptions, particularly in the Western genre. Senorita Scorpion, the creation of Les Savage, Jr. (1922-1958), wasn’t actually the first pistol-packing cowgirl to be featured in the Western pulps of the 30s and 40s; but she proved to be the most popular, one of the most unique, and probably the subject of the longest running and thickest corpus of material of any of these fictional ladies: seven stories, originally published in Action Stories from 1944-49. Through its Altus Press imprint, (CreateSpace is just the printing service) Pro Se Press seeks to bring the best fiction of the early modern pulp magazine era back into print, in book form now, for a new generation of fans. These stories (plus one by Emmett McDowell, which used the Senorita Scorpion name for an entirely different character) were a felicitous choice for one of their first projects, in two volumes. From this beginning, the first four stories proceed in a chronological arc; each is self contained, but the following ones build on the preceding ones in terms of character and situational development, so that what we have is a genuine story cycle. In the later three stories, the chronological relationship to the rest of the corpus isn’t as clear, except that they all take place after the events of the first story, and that “Lash of the Six-Gun Queen” is set near the end of the decade. Savage makes statements inconsistent in details with what he wrote earlier in one story, and another tale also gives some evidence of forgetfulness on his part. The rest of the Douglas clan simply disappears in the later stories, and their unique sociological circumstances aren’t explored at all, while the Santiago Ranch functions about like a set or a piece of furniture; there’s not much attention to its fortunes or the practicalities of running it. Elgera’s supposedly well-known skill at cards is only brought out in “Brand of the Gallows-Ghost,” and never mentioned elsewhere.

From this beginning, the first four stories proceed in a chronological arc; each is self contained, but the following ones build on the preceding ones in terms of character and situational development, so that what we have is a genuine story cycle. In the later three stories, the chronological relationship to the rest of the corpus isn’t as clear, except that they all take place after the events of the first story, and that “Lash of the Six-Gun Queen” is set near the end of the decade. Savage makes statements inconsistent in details with what he wrote earlier in one story, and another tale also gives some evidence of forgetfulness on his part. The rest of the Douglas clan simply disappears in the later stories, and their unique sociological circumstances aren’t explored at all, while the Santiago Ranch functions about like a set or a piece of furniture; there’s not much attention to its fortunes or the practicalities of running it. Elgera’s supposedly well-known skill at cards is only brought out in “Brand of the Gallows-Ghost,” and never mentioned elsewhere.