[Click pics to enlarge]

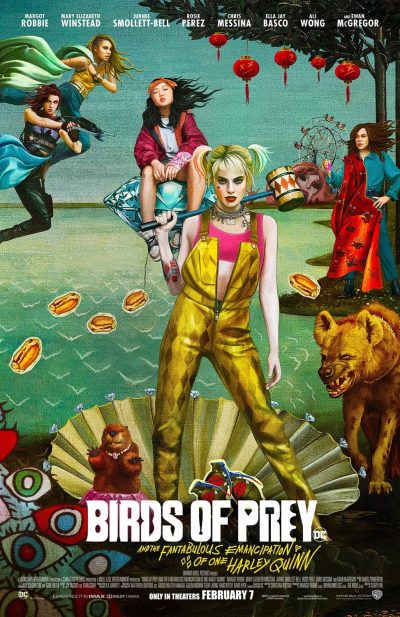

Birds of Prey

[Click pics to enlarge]

[Click pics to enlarge]

Or, to give this its full, rather misguided name: Birds of Prey (and the Fantabulous Emancipation of One Harley Quinn). I am not convinced that films are improved by giving them gimmick titles including made-up words. It smacks rather of desperation on the part of the makers. Though this is… alright. It did not actively annoy me in quite the same way Captain Marvel did, but it is still disappointing. Robbie’s Harley Quinn was easily the best thing about Suicide Squad. She’s also the best thing about this, but it feels at a considerably lower level. All the edges seem to have been filed off, with Robbie (who produced this and came up with the idea) apparently intent on making her much more of a heroic figure than the barely-restrained psychopath I was hoping to see.

Or, to give this its full, rather misguided name: Birds of Prey (and the Fantabulous Emancipation of One Harley Quinn). I am not convinced that films are improved by giving them gimmick titles including made-up words. It smacks rather of desperation on the part of the makers. Though this is… alright. It did not actively annoy me in quite the same way Captain Marvel did, but it is still disappointing. Robbie’s Harley Quinn was easily the best thing about Suicide Squad. She’s also the best thing about this, but it feels at a considerably lower level. All the edges seem to have been filed off, with Robbie (who produced this and came up with the idea) apparently intent on making her much more of a heroic figure than the barely-restrained psychopath I was hoping to see.

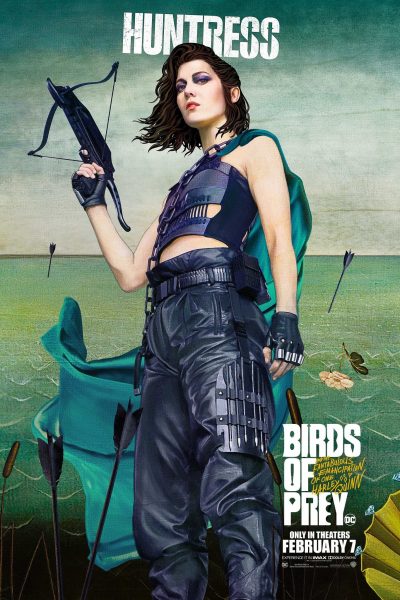

The main problem, however, is over-stuffing of storylines, with so many threads being weaved in, that they all inevitably suffer as a result. Let’s enumerate them. There’s Harley, who breaks up with the Joker, only to discover his protection was the only thing which had been keeping her safe. Detective Renee Montoya (Perez), whose case-load includes investigating crossbow vigilante killings, mob boss Roman Sionis (McGregor) and Harley herself. Sionis’s singer-turned-driver Dinah Lance, a.k.a. Black Canary (Jurnee Smollett-Bell), who… Well, I’m really not sure what purpose she serves here. The crossbow killer is Helena Bertinelli, a.k.a. Huntress (Winstead), seeking vengeance for the death of her family. And Cassandra Cain (Ella Jay Basco), a young pickpocket who steals and eats a diamond containing coded information sought by Sionis.

None of these are adequately developed, even Harley’s. Her story is adequately and brightly sketched out in an animated opening sequence, and then gets scant service as the script tries to keep all its balls, sorry, ovaries in the air. For the feminist leanings are probably the most painful aspect. As depicted here, the “emancipation” of the title seems less about building women up, than tearing men down. Virtually without exception, every male character is more or less a bastard, from the obvious ones like Sionis’s sidekick with a fondness for face-peeling through to Montoya’s former partner who stole credit for her work. Even the kindly store-owner turns out to be happy to sell Harley out. Is this emancipation? To steal from The Princess Bride: “You keep using that word, I do not think it means what you think it means.”

Along those lines I was initially prepared to criticize Margot for pre-release statements, like it being “hugely important to find a female director for this.” However, that snippet is a bit misleading, since the full quote in context goes on, “…if possible. But at the end of the day — male, female — the best director gets the job and Cathy was the best director.” I’m fine with that. Though it has to be said, I’m not sure what made Yan the best, given her only feature before this was Dead Pigs, a comedy-drama about an incident where 16,000 deceased porcines were found in a Chinese river. But the direction here is serviceable enough: it doesn’t get in the way of Margot Robbie, which may be what the star wanted all along.

The action is a bit of a mixed bag. There are a couple of very good brawls for Harley, most notably one in a police evidence warehouse (even if the cops seem curiously unwilling to draw and use their firearms. What is this, the United Kingdom?) where Robbie and her stunt doubles get to showcase some stellar moves. But the final fight has much the same problem as the plot in general. In trying to make sure each of the four fighting leads get their chance to shine (Cassandra basically cowers in a corner for the duration of it), the climax basically succeeds in selling all of them short. There is quite a nice “funhouse” atmosphere there, since it takes place in an abandoned amusement park, though it feels like some of the potential wasn’t fully developed.

The action is a bit of a mixed bag. There are a couple of very good brawls for Harley, most notably one in a police evidence warehouse (even if the cops seem curiously unwilling to draw and use their firearms. What is this, the United Kingdom?) where Robbie and her stunt doubles get to showcase some stellar moves. But the final fight has much the same problem as the plot in general. In trying to make sure each of the four fighting leads get their chance to shine (Cassandra basically cowers in a corner for the duration of it), the climax basically succeeds in selling all of them short. There is quite a nice “funhouse” atmosphere there, since it takes place in an abandoned amusement park, though it feels like some of the potential wasn’t fully developed.

It does seem to draw some inspiration from Leon, in the relationship between Harley and Cassandra, which is not dissimilar to the one between Leon and Matilda. In both, the adult is forced to tap into a previously unknown nurturing side after a young girl is dropped into their care, though they are hardly the ideal parent. But probably the most obvious nod is at the end, where Cassandra pulls a very similar “ring trick” to the one which takes care of Stansfield at the end of Leon. As soon as she said it, I figured out what Cassandra meant, before Harley did. However, this maternal element does play into the softening of Harley, one of the disappointing aspects. Given the freedom of an R-rating. I’d have expected a bit more in the way of mature content than a potty mouth and some intermittently brutal violence. At times, it feels more like Robbie is cosplaying Harley, rather than playing her.

Robbie’s avowed aim was to make a “girl gang” pic, perhaps inspired by things like Switchblade Sisters, Faster Pussycat or the pinky violence genre. But what she didn’t bring from them, is that those all had strong leadership. There was no doubt that Tura Satana or Meiko Kaji were the stars: the films accordingly orbited around them and their fabulous screen presence. Her previous movies have shown us, Robbie can deliver that, which makes it all the more of a shame that she abdicated the throne here. Sadly, this ends up closer to an episode from the last series of Doctor Who, with its “very flat team structure.” Or to borrow from Monty Python and the Holy Grail, an anarcho-syndicalist commune where Harley and her pals take it in turns to act as a sort of executive officer for the week. Maybe the title, with its supposed heroine relegated to the tenth and eleventh words, was accurate after all.

Dir: Cathy Yan

Star: Margot Robbie, Ewan McGregor, Mary Elizabeth Winstead, Rosie Perez

This was a genuine and pleasant surprise. The original release was pushed back due to some severe controversy: not many films get Tweeted about by the President of the United States, who stated this was “made in order to inflame and cause chaos.” Needless to say, the studio ended up riding that publicity when the movie eventually came out. The current pandemic ended up trumping that (pun intended), so the film hit the home markets, just a week after its theatrical release. To my surprise, it’s considerably more nuanced than the “Red State vs. Blue State” concept I expected. And Gilpin has clearly put her GLOW training to good use, becoming quite the thirty-something bad-ass here.

This was a genuine and pleasant surprise. The original release was pushed back due to some severe controversy: not many films get Tweeted about by the President of the United States, who stated this was “made in order to inflame and cause chaos.” Needless to say, the studio ended up riding that publicity when the movie eventually came out. The current pandemic ended up trumping that (pun intended), so the film hit the home markets, just a week after its theatrical release. To my surprise, it’s considerably more nuanced than the “Red State vs. Blue State” concept I expected. And Gilpin has clearly put her GLOW training to good use, becoming quite the thirty-something bad-ass here.

It is, at its heart, another variant on The Most Dangerous Game, with a dozen people being kidnapped from their everyday lives, and taken somewhere that looks much like Arkansas, to be hunted by the rich for sport. The film is very good in the earlier stages at disconcerting the viewer by shifting their focus: you’ll settle in with one character, only for them to be wiped out in brutal fashion. Gilpin’s character, Crystal Creasey, isn’t even seen until more than 25 minutes in. But she makes up for her late arrival in no uncertain style, quickly establishing that the people behind the hunt, led by Athena (Swank), might have made a mistake by selecting Crystal as their entertainment.

What I found interesting is how even-handed this is. Yes, it’s about the elite hunting common people, and on its surface, i.e. the trailer, could be seen as Democrats hunting Republicans. But they’re hardly depicted as heroic, and indeed, it turns out, there’s considerably more to this. The whole thing started as an off-colour joke by Athena that got out, causing the wrath of #CancelCulture, as propagated through social media and conspiracy circles. She then decided, if we’re going to be blamed for something we didn’t do – why not do it anyway, and targets those who were her harshest critics on social media? Neither side gets out unscathed: not the liberals with their virtue signalling and hypocrisy, nor the conservatives with their paranoia and self-deceit. Yes, it is certainly guilty of picking at the raw scab which is the divided state of the nation (something for which the media, in general, must take much of the blame).

But the horror movie as social commentary is something that has been around for at least fifty years, since Night of the Living Dead. As I’ve previously made clear, I’m fine with that, providing the film works regardless. And you could safely ignore all the satirical aspects, and you’d still have something among the upper tier of movies inspired by The Most Dangerous Game. It all builds to a kitchen battle between Crystal and Athena, that for sheer savagery, is one of the best woman-on-woman brawls I’ve seen since Kill Bill, Volume 2. Providing you are not too blinkered in your political views, the payoff here should be worth putting them to one side for ninety minutes.

Dir: Craig Zobel

Star: Betty Gilpin, Ike Barinholtz, Amy Madigan, Emma Roberts

This may be a first, in that the heroine here is non-human – contrary to what you (and, indeed, I!) might expect from the cover. I think I may have covered various crypto-humans before, such as vampires or elves. But this is likely the first entirely alien species. I began to suspect on page 1, when I read that Sah Lee “sank her pin-sharp teeth through the thick fur of the calf’s throat, and tasted the sweet metallic tang of its young blood.” This is clearly not your average twelve-year-old. And so it proves. The story really kicks under way two years later, when Sah Lee leaves her rural village on the planet of Aarn to attend school in the city of Aa Ellet.

This may be a first, in that the heroine here is non-human – contrary to what you (and, indeed, I!) might expect from the cover. I think I may have covered various crypto-humans before, such as vampires or elves. But this is likely the first entirely alien species. I began to suspect on page 1, when I read that Sah Lee “sank her pin-sharp teeth through the thick fur of the calf’s throat, and tasted the sweet metallic tang of its young blood.” This is clearly not your average twelve-year-old. And so it proves. The story really kicks under way two years later, when Sah Lee leaves her rural village on the planet of Aarn to attend school in the city of Aa Ellet.

She is out of town on a class trip, when demons descend from the sky, causing massive death and destruction. Of course, they’re actually an alien tribe known as “outcasts”, who specialize in this kind of thing. But Sah Lee being a pre-first contact civilization, demons it is. Eventually, the rest of the galaxy, led by the super-advanced group known as “the People”, come to the rescue, but by that point, the planet is uninhabitable and most of the Aarnth dead. Sah Lee is taken aboard a ship, and vows to take revenge on the outcasts by any means necessary, which involves joining one of the galactic armies. But there will be a period of sharp adjustment from the pastoral life she had on Aarn, to being an interstellar soldier. Not drinking out of the toilet will be a start.

It’s not quite clear what Sah Lee is. Mammalian, to be sure – and that’s significant, since one of the features of the universe depicted here is that it is peopled not just by mammals, but reptilians, avians and even insectoid species, generally (but not universally) getting along. Thank heavens for universal translators. Anyway, something cat-like is probably my best guess, though quite how… furry she is, is never established. It doesn’t matter much though: her story is what’s important. And this is at its best in the relatively early stages: seeing an alien invasion from the side of the natives, then following Sah Lee as she has to adjust to a radically new and unimaginably different life. It makes me wonder what first contact will be like for Earth, when it finally happens. Potentially not good.

It’s rather less effective one she settles in, becoming fairly standard space opera. Through a special relationship with the People, Sah Lee has a cutting-edge AI and tech which does make her a bit super-powered. She breezes through every situation, even getting harshly disciplined after breaking military protocol (albeit for good reason). I’m also very unsure of the timeframe here. By the end, she’s basically in charge of her own army, and I’m guessing she is no longer a teenager. Not least because the galaxy as a whole has more or less conquered disease, meaning that violent death is about the only thing preventing near-immortality, with one character being over 172,000 years old. But again, it’s just not clear.

It is, at least, a self-contained story, rather than being volume one of a saga. The book reaches its end at an appropriate and generally satisfying point, which could go on, yet doesn’t have to. I’d have been very interested at the half-way point, when this was offering a different and original perspective on a super-advanced society – looking at it from the bottom up. Now Sah Lee is no longer in that position, she has become considerably less appealing.

Author: Andrew Maclure

Publisher: Amazon Digital Services, available through Amazon, as an e-book only.

When I settled in to view this, I didn’t realize it starred Weaving, who was the best thing about the very entertaining Guns Akimbo. She’s also the best thing about this, and it largely solidifies my opinion that she’s one to watch in the future. By the end of this, her character has gone through an absolute meat-grinder of punishment, and she is literally drenched in gore. It’s all a very slight work, a comedy-horror that skews heavily towards the first of its genres, and is little more than a disposable bit of fluff. But I’m a sucker for a spot of wedding-dress mayhem – see also Queen’s High and Bloody Mallory.

When I settled in to view this, I didn’t realize it starred Weaving, who was the best thing about the very entertaining Guns Akimbo. She’s also the best thing about this, and it largely solidifies my opinion that she’s one to watch in the future. By the end of this, her character has gone through an absolute meat-grinder of punishment, and she is literally drenched in gore. It’s all a very slight work, a comedy-horror that skews heavily towards the first of its genres, and is little more than a disposable bit of fluff. But I’m a sucker for a spot of wedding-dress mayhem – see also Queen’s High and Bloody Mallory.

Weaving plays Grace, about to be married to Alex (Brody), a son from the rich Le Domas family, who made their money in cards, board games and sports teams. The wedding is taking place at their immense country mansion, with his family largely looking down their noses at Grace, believing her to be a gold-digger. Family tradition has new members pulling a card with a game on it, which they must then play. Except, Grace draws “Hide and Seek”. Which means she gets to hide, and quickly discovers that if found, she’ll be killed. This is the result of a pact with the devil made generations ago, the source of the Le Domas fortunes, which on occasion requires a sacrifice. Tonight being that occasion, and Grace being that sacrifice.

The main problem here is, the family are so inept as to pose no credible threat whatsoever. They may have the benefit of numbers, and operate on home-turf as well. Yet they are, in fact, more of a danger to each other or their (rapidly diminishing number of) servants than to Grace. In their defense, it’s not often that their sponsor demands blood, so it’s not as if they’re experienced at ritual murder. Still, is a basic degree of competence too much to ask? Instead, they spend much of the night bumbling around and/or bickering with each other, and it’s not as funny as it thinks. I will exempt Aunt Helene (Nicky Guadagni) from this, who has both an appropriately brutal approach and a nice line in deadpan familial snark. e.g. on being greeted by a disliked relative, she responds with, “Brown-haired niece. You continue to exist.”

I get the feeling there is some class criticism going on here, albeit at a lower level than, say, Knives Out, so that can safely be ignored. For it’s the Samara show, and whenever we are watching Grace’s beautiful wedding-dress disintegrate into a blood-drenched mess, it’s an unexpected delight, especially since Alex is next to useless. I’m not sure I’ve seen such a character arc, going from victim to bad-ass so completely, since Evil Dead II. I also did enjoy the ending, which looked like it was going to zig, before zagging in no uncertain terms. While it would have been nice to see Grace administering the startlingly messy coup de grace, I’m okay with settling for what we get.

Dir: Matt Bettinelli-Olpin, Tyler Gillett

Star: Samara Weaving, Adam Brody, Mark O’Brien, Henry Czerny

Regardless of its flaws, this does at least show that comic-book adaptations needn’t involve superheroes and Thanos snaps. This is instead a crime story, beginning towards the end of the seventies in Hell’s Kitchen, a working-class area of New York. Following a failed armed robbery, the husbands of Kathy (McCarthy), Ruby (Haddish) and Claire (Moss) are sent to jail, leaving the wives to fend for themselves. To make ends meet, the trio begin to move in on the territory of local boss Little Jackie, who has been taking money from local businesses, without delivering the promised protection. When Jackie goes after them, he is killed by the women’s ally, Gabriel (Gleeson), who begins a relationship with Claire. But the husbands’ return to Hell’s Kitchen looms on the horizon, as the women’s growing power also brings them unwelcome attention – both from the authorities and the Mafia who dominate the city.

Regardless of its flaws, this does at least show that comic-book adaptations needn’t involve superheroes and Thanos snaps. This is instead a crime story, beginning towards the end of the seventies in Hell’s Kitchen, a working-class area of New York. Following a failed armed robbery, the husbands of Kathy (McCarthy), Ruby (Haddish) and Claire (Moss) are sent to jail, leaving the wives to fend for themselves. To make ends meet, the trio begin to move in on the territory of local boss Little Jackie, who has been taking money from local businesses, without delivering the promised protection. When Jackie goes after them, he is killed by the women’s ally, Gabriel (Gleeson), who begins a relationship with Claire. But the husbands’ return to Hell’s Kitchen looms on the horizon, as the women’s growing power also brings them unwelcome attention – both from the authorities and the Mafia who dominate the city.

More than slightly reminiscent of Widows, this is considerably less plausible. The area at the time was controlled by the Westies, a powerful Irish-American group, and the film gives you little or no reason to believe why they’d roll over and let a bunch of amateurs – and women at that – muscle in and take over. In reality, I strongly suspect they’d be squashed like bugs at the first collection of protection money. One woman leading a crew might be possible (see Dangerous Lady for a good example); tripling down, as the movie does, stretches credibility to breaking point. It doesn’t help that there is only one decent character arc between them. That belongs to Claire, who goes from abused wife and perpetual victim, to the group’s enforcer under the tutelage of Gabriel. One of the film’s best scenes has him giving a lesson on dismembering a body to dispose of it. Kathy can’t watch at all, and Ruby is similarly appalled; Claire is entirely fascinated. It’s clear something has been awakened inside. And her incarcerated husband isn’t going to like it much.

It’s a shame she is largely relegated to the sidelines, being the most interesting of the trio – as well as the one most suited to this site, as the poster suggests. Instead, it’s mostly the blandly uninteresting Kathy who takes centre-stage. Even Ruby would have been an improvement, her black heritage adding an element of racial tension, with her husband’s family reluctant to accept her into their bosom. We’re also asked to accept them as heroines without explanation, ignoring the inherently scummy nature of the protection racket which they operate. But they’re nice about it, so that’s okay! Then again, I’ve never bought into the “They’re just taking care of their family” excuse, especially when, as here, efforts to get gainful, legal employment are all but absent. Berloff seems to be aiming for a Scorsese-like approach, down to the use of contemporary pop songs as a commentary on proceedings. While there are worse auteurs to ape, you’ll likely be left with little more than a desire to go watch Goodfellas.

Dir: Andrea Berloff

Star: Melissa McCarthy, Tiffany Haddish, Elisabeth Moss, Domhnall Gleeson

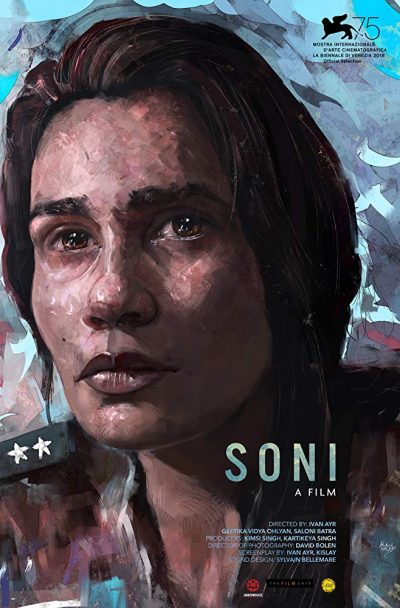

This takes place in the Indian city of Delhi, and despite the title and the poster, is really about two policewomen, almost equally. Title billing goes to Soni (Ohlyan), a young officer who is coming to terms with life after divorce from her husband, Naveen (Shukla). She is also the possessor of a fierce temper, which repeatedly gets her into trouble because she’s unable to keep her cool with suspects. Forced to play clean-up is her boss, superintendent Kalpana Ummat (Batra), who seems to see something of her younger self in Soni, as well as appreciating the junior cop’s potential. But there’s only so far she can protect Soni from the consequences of her outbursts.

This takes place in the Indian city of Delhi, and despite the title and the poster, is really about two policewomen, almost equally. Title billing goes to Soni (Ohlyan), a young officer who is coming to terms with life after divorce from her husband, Naveen (Shukla). She is also the possessor of a fierce temper, which repeatedly gets her into trouble because she’s unable to keep her cool with suspects. Forced to play clean-up is her boss, superintendent Kalpana Ummat (Batra), who seems to see something of her younger self in Soni, as well as appreciating the junior cop’s potential. But there’s only so far she can protect Soni from the consequences of her outbursts.

Ayr is going for a documentary feel here, using a lot of hand-held camera and single takes, which makes it seem as if the movie is following the characters, rather than them acting as directed. The problem is that there just isn’t enough in the script to sustain interest: we are not, for example, following Soni through the investigation of one particular case which could have acted as a common thread, tying things together. Instead, we get a series of semi-random incidents, which are more or less the same. Soni gets involved in an incident. Soni loses her temper after a man says something bad to her. Soni hits the man. Her superior officer has to deal with the aftermath. There are at least three cycles of the above, which is probably two too many. She literally can’t even go to the bathroom, without a fight breaking out.

That said, the policing aspects are still quite interesting, and I don’t envy either of the women, doing what has to be a thankless job; if this depiction is correct, Indian society is still inhabiting the Stone Age as far as gender equality is concerned. But even that aside, you’re picking the bones out of cases which are rarely clear-cut. For instance, one alleged sexual assault here might be nothing more than a dispute about rent, as Soni suspects, or may be legitimate, as Kalpana reckons. Figuring out the truth in these situations is as much an art as a science, and it’s here, as well as in negotiating the shoals of political influence, where the movie works best.

Unfortunately, it’s dragged down heavily, by the weight of the two women’s personal lives, which are tedious and uninteresting. Soni’s ex-husband keeps trying to get them back together; Kalpana has to deal with a husband, also a police officer, who outranks her, and a mother-in-law who is demanding grandchildren. This is all sub-telenovela rubbish, and doesn’t seem to add any informative or enlightening angles to either character. It also becomes more than slightly monotonous in its gender depictions, with men shown almost inevitably as lecherous, venal, corrupt or, at the very least, blindly indifferent. The lack of any true conclusion may be “realistic,” yet instead provides a final nail in the coffin.

Dir: Ivan Ayr

Star: Geetika Vidya Ohlyan, Saloni Batra, Vikas Shukla, Mohit S. Chauhan

There’s nothing wrong, as such, with a film playing its hand close to its chest. However, you’ve got to give the audience enough information to keep them interested, and wanting to find out more. It’s here that this movie fails entirely, doggedly remaining so reluctant to tell you anything, I wanted to strap it down in a chair and start waterboarding. We don’t even get names for anyone involved, it’s that willfully unforthcoming. This begins in the aftermath of a shoot-out at a wind-farm, from which there are apparently only two survivors: a woman (Szep) and her captive (de Francesco). They head across the rural terrain towards a rendezvous with her allies, pursued not only by the captive’s allies, but also other interested parties.

There’s nothing wrong, as such, with a film playing its hand close to its chest. However, you’ve got to give the audience enough information to keep them interested, and wanting to find out more. It’s here that this movie fails entirely, doggedly remaining so reluctant to tell you anything, I wanted to strap it down in a chair and start waterboarding. We don’t even get names for anyone involved, it’s that willfully unforthcoming. This begins in the aftermath of a shoot-out at a wind-farm, from which there are apparently only two survivors: a woman (Szep) and her captive (de Francesco). They head across the rural terrain towards a rendezvous with her allies, pursued not only by the captive’s allies, but also other interested parties.

I’ll fill in some of the background, since the movie is painfully averse to doing so. There is a looming, if not already happening, ecological catastrophe, which will result in the loss of all potable water. This may potentially lead to the collapse of civilization, particularly in the more crowded Northern hemisphere. The 1% are aware of the impending situation, and are plotting to head south, taking over resources there for their own benefit – in particular, a large underground water source. This is what the captive was involved in, and what the woman is attempting to prevent. Yet there may also be other, hidden agendas.

The interplay between the two leads is probably the best thing about this, with trust hard to come by on either side. For instance, just before bedding down, he asks her, “What makes you think I won’t slit your throat in the middle of the night?” Her reply, which genuinely made me LOL: “Probably the ketamine I laced your food with,” just as he falls unconscious. It’s a shame their relationship operates in such a vacuum, as far as reasons to care go. Both she and he clearly know what’s happening here: they’re just unwilling to share this data with the audience, and the result is a low-intensity apathy. Which is a bit of a pity, since Szep is decent, a low-rent version of Rhona Mitra, and the pursuing group is led by another unnamed woman (Walker). Say what you like about this dystopian future, at least it’s clearly an equal opportunity one.

The scenery is quite nice, and well-photographed too, though I was a bit confused by the lobbing in of some South African references. I guess it’s all Southern Hemisphere. There’s also a scene where the woman just lets her captive run off, because… Well, like just about everything else here, it goes unexplained. Perhaps the most telling point is, I actually ended up watching this twice, because the first time, I got an hour in and realized I had no real clue what was happening. I blamed this on my having been distracted somehow, so restarted it. Nope. A second viewing proved it was truly a case where it was the movie’s fault, and not mine.

Dir: Michael Hatch

Star: Paris Szep, Vito de Francesco, Alyson Walker, Benjamin Francis Pascoe

Harry Potter, this is not. If it’s difficult to separate Radcliffe from the hero of the movie franchise, this is the kind of film which should help considerably. He plays Miles, a computer programmer and online troll, who trolls the wrong people. Specifically, the ones who run Skizm, an increasingly popular and hyper-violent online streaming service, which broadcasts death-matches between contestants. For his sins, Miles is knocked out, and wakes to find himself with guns bolted to both hands. He is now Skizm’s latest contestant, going up against their reigning champion, Nix (Weaving). And to encourage him, the man who runs the game, Riktor (Dennehy), has kidnapped Miles’s intermittent girlfriend, Nova (Bordizzo). To survive, he’s going to need help from a most unusual source: Nix.

Harry Potter, this is not. If it’s difficult to separate Radcliffe from the hero of the movie franchise, this is the kind of film which should help considerably. He plays Miles, a computer programmer and online troll, who trolls the wrong people. Specifically, the ones who run Skizm, an increasingly popular and hyper-violent online streaming service, which broadcasts death-matches between contestants. For his sins, Miles is knocked out, and wakes to find himself with guns bolted to both hands. He is now Skizm’s latest contestant, going up against their reigning champion, Nix (Weaving). And to encourage him, the man who runs the game, Riktor (Dennehy), has kidnapped Miles’s intermittent girlfriend, Nova (Bordizzo). To survive, he’s going to need help from a most unusual source: Nix.

This is the kind of incessantly kinetic, brutal action film that you’ll probably either love or hate. I was pushed firmly into the latter company by Samara Weaving, who is a coke-snorting, chain-gun wielding, spiky package of undiluted and venomous awesome. While Miles is the nominal lead character, Nix was considerably more fun to watch, and also has the better character arc. For example, her actions have considerably better motivations, considering Miles is basically trolling for the LOLs. There’s plenty of her in action to appreciate too, pushing this out of the “supporting girl with gun” category into qualification. I haven’t yet seen Birds of Prey, but suspect Weaving would have been an admirable alternate to Margot Robbie.

I’m interested, if somewhat confused, about the moral message being sent here – or whether there is one at all. It’s both condemning the audience for violent entertainment… while, very clearly, feeding that same appetite. Any sense of intellectual superiority over the masses is similarly undercut by the extremely low-brow humour. Have you ever considered how hard it would be to go to the bathroom with your hands locked around firearms? Me neither. But with his writer’s cap on, Howden clearly has. Yet this does help insulate the film from suggestions of hypocrisy, its broken spiritual compass and disjointed one-liners a fitting match for the ADHD and morally bankrupt world it is depicting. Though the most implausible thing here, might be the way Miles’s fuzzy slippers stay on. I can’t even go down the stairs without mine making a bid for independence from my feet.

The action is almost non-stop, and the blood flows in rivers, to the point that it becomes almost a caricature of the more extreme end of video-gaming. It’s staged fairly well, though does occasionally topple over into the manic style of editing which is the bane of modern cinema. Things build towards the expected climax, in which Miles and Nix mount an all-out assault on Riktor’s headquarters, delivering one final shot of adrenaline-powered hyper-mayhem to your lizard brain. If not all the characters receive quite the fate you want, there’s enough here to make me believe Weaving has action heroine superstar potential.

Dir: Jason Lei Howden

Star: Daniel Radcliffe, Samara Weaving, Natasha Liu Bordizzo, Ned Dennehy

The first volume in the Imp series, A Demon Bound, was one of the most entertaining books I’ve read of late. It told the story of Samantha Martin, the human vessel occupied by a demon “who has chosen to spend her life among us mortals, rather than in the underworld… largely because it’s more fun up here.” I was thus stoked to read the next two entries in the series, with Sam’s further adventures. She’d ended the series having been “bound” to an angel, Gregory, and in the subsequent parts, this is now causing issues for both of them. He is getting flak from his colleagues for his association with her, while she is experiencing unfamiliar emotions, such as loyalty and kindness.

The first volume in the Imp series, A Demon Bound, was one of the most entertaining books I’ve read of late. It told the story of Samantha Martin, the human vessel occupied by a demon “who has chosen to spend her life among us mortals, rather than in the underworld… largely because it’s more fun up here.” I was thus stoked to read the next two entries in the series, with Sam’s further adventures. She’d ended the series having been “bound” to an angel, Gregory, and in the subsequent parts, this is now causing issues for both of them. He is getting flak from his colleagues for his association with her, while she is experiencing unfamiliar emotions, such as loyalty and kindness.

It makes sense to cover both of these as one volume, as they combine to represent a significant story arc. The main thread in that is her hell-spawned brother, Dar, has got in the bad graces of upper-tier demon, Haagenti. Unfortunately, that escalates into Haagenti putting out an infernal hit on Sam – as well as those she cares about, in particular her all-too human boyfriend, Wyatt. To deal with that, she ends up taking on a job for an elven lord, locating the offspring of an unfortunate liaison between an elf and a succubus – the latter just happening to be Sam’s foster sister, Leethu.

The main problem, I felt, was Dunbar over-stuffed these books with ideas. If she’d stuck to the basic concept above, and developed it properly, it might have worked a bit better. Instead, there are any number of threads which feel undercooked, to a greater or less degree. For example, the serial killer targetting Sam’s slum tenants, or the teenage boys who managed to summon her, courtesy of a ritual they found on the Internet. The latter feels especially rife with potential, sadly never realized. Or the heavenly bureaucracy in which Sam gets entangled, complete with committee meetings and detailed reports. I’d rather have heard more about these fascinating and amusing ideas, than the detailed discussion concerning the breeding habits of elves we get.

Fortunately, the heroine remains as wonderfully twisted a character as ever. Though I must confess, the angel influence is a little worrying, given what made Sam so deliciously bad was her complete lack of scruples. For when you are all but immortal, you can afford to push other entity’s buttons – such as when she manages to goad another angel into an all-out brawl during one of those committee meetings. There may have been a stale Danish pastry involved. If this sardonic edge becomes dulled due to the angelic influence, it would be a real shame, since it’s one of the main things which makes Sam stand out in the field of literary action-heroines. We’ll see what happens as we go forward in the series.

Author: Debra Dunbar

Publisher: Volumes 1-3 are available as an omnibus from Anessa Books, available through Amazon, as an e-book

Books 1-3 of 10 in the Imp series.