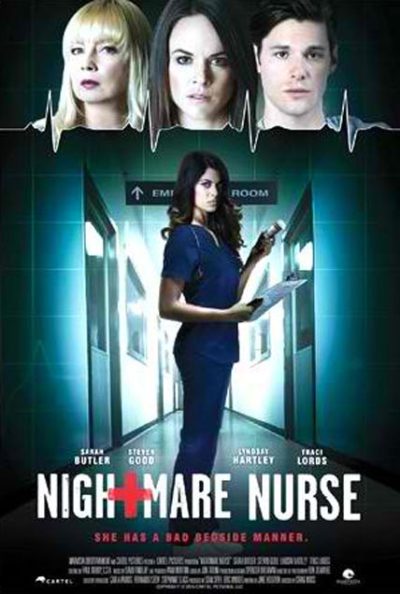

★★

“Nurse shark.”

This Lifetime TV movie is the story of Brooke (Butler) and Lance (Good). The happy young couple get into an accident returning from celebrating her promotion at the restaurant where she works. The pedestrian they hit is killed, while Lance breaks his leg, and is confined to bed while he recuperates. To assist with that task, since Brooke has to work, they hire Chloe (Hartley). She initially appears perfect for the job, helping out with the household chores as well as her nursing work. However, it’s not long before strange little incidents suggest that not all is well in Chloeland. We see her life with an abusive boyfriend, and she develops an attachment for Lance well beyond the normal bounds of professional concern. Might this, possibly, be something to do with the accident?

This Lifetime TV movie is the story of Brooke (Butler) and Lance (Good). The happy young couple get into an accident returning from celebrating her promotion at the restaurant where she works. The pedestrian they hit is killed, while Lance breaks his leg, and is confined to bed while he recuperates. To assist with that task, since Brooke has to work, they hire Chloe (Hartley). She initially appears perfect for the job, helping out with the household chores as well as her nursing work. However, it’s not long before strange little incidents suggest that not all is well in Chloeland. We see her life with an abusive boyfriend, and she develops an attachment for Lance well beyond the normal bounds of professional concern. Might this, possibly, be something to do with the accident?

Oh, who am I trying to kid. This is a Lifetime TV movie. Of course it has something to do with the accident, although the precise details are vague until the final 20 minutes. Which are actually when the film raised itself beyond the painfully humdrum, not least because of the return of Traci Lords. She plays “good” nurse Barbara, in what initially appears to be a glorified cameo, yet ends up an extremely pivotal role. Lords wipes the floor with the rest of the cast, and it’s a shame she is almost absent from the first hour. [It has to be said, knowledge of her past adds to the frisson here; she wouldn’t exactly be the person most women would want caring for their boyfriends!] The final battle, as Brooke defends her territory like a lioness, is certainly the most fun this has to offer.

Unfortunately, you have to get through an awful lot of Very Obvious to reach that point. Naturally, it’s another sensitive and sympathetic portrayal of mental illness and the stigma faced by those who suffer fro… Oh, again – who am I trying to kid? Chloe is as batty as a fruitcake, whose direction appears to be the result of viewing Fatal Attraction. Except, Hartley isn’t exactly Glenn Close, no matter how wide she opens her eyes and stares really hard. She’d have been better off watching Nurse 3D, and taking lessons in scenery-chewing from Paz de la Huerta. Butler and Good are serviceable enough as the perfect couple with impeccable teeth. Though I’m surprised Lance remains faithful, given the Lifetime tendency for all men to be unreliable in the loyalty department.

It just about stays on the acceptable side of entertainment, until the final reel. However, the main thing you’ll take from that is how much more entertaining it all might have been, if the makers had Lords play Chloe instead.

Dir: Craig Moss

Star: Sarah Butler, Steven Good, Lyndsay Hartley, Traci Lords

On the other hand, if the plot has more than some similarities, the tone and approach are different here. There’s much more in the way of social commentary here, with the disparate personas of the two young women. [Indeed, so disparate, you have to question how the heck they ever ended up sharing a house] Jamie (Vega) is serious-minded, the kind of person who labels her food in the fridge, and seeking to pursue an academic career, but desperately needs funds to cover tuition at her chosen college. Dee (Grammer) is a party girl, whose days are filled with going to the gym and tanning, while her nights are filled with tequila and casual sex.

On the other hand, if the plot has more than some similarities, the tone and approach are different here. There’s much more in the way of social commentary here, with the disparate personas of the two young women. [Indeed, so disparate, you have to question how the heck they ever ended up sharing a house] Jamie (Vega) is serious-minded, the kind of person who labels her food in the fridge, and seeking to pursue an academic career, but desperately needs funds to cover tuition at her chosen college. Dee (Grammer) is a party girl, whose days are filled with going to the gym and tanning, while her nights are filled with tequila and casual sex.

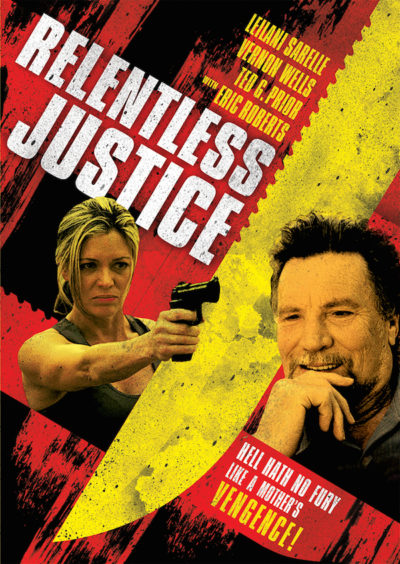

Nicole Johnson (Sheridan) comes home with her daughter to find a robbery in progress, but is a well-armed home-owner and ends up blowing away one of the intruders. The other, Ray (Howell), bails with their getaway driver, Jade (Duff), who was also the dead perp’s girlfriend. She vows to take vengeance on Nicole and her family, in a variety of forms, from posing as a swimming teacher, to poisoning the customers at Nicole’s restaurant, then setting the place on fire and framing her for arson. Plus, of course, she’s a believer in the old Biblical law of an eye for an eye – or, in this case, a boyfriend for a boyfriend, Jade fixing to inject her nemesis’s other half with that old “undetectable poison”, potassium chloride. I have probably just got myself on a government watch-list by Googling that. Should have done it on my boss’s computer. Oh, well….

Nicole Johnson (Sheridan) comes home with her daughter to find a robbery in progress, but is a well-armed home-owner and ends up blowing away one of the intruders. The other, Ray (Howell), bails with their getaway driver, Jade (Duff), who was also the dead perp’s girlfriend. She vows to take vengeance on Nicole and her family, in a variety of forms, from posing as a swimming teacher, to poisoning the customers at Nicole’s restaurant, then setting the place on fire and framing her for arson. Plus, of course, she’s a believer in the old Biblical law of an eye for an eye – or, in this case, a boyfriend for a boyfriend, Jade fixing to inject her nemesis’s other half with that old “undetectable poison”, potassium chloride. I have probably just got myself on a government watch-list by Googling that. Should have done it on my boss’s computer. Oh, well….