★★★½

“I can only apologize.”

Not for the show, I should stress. But as a Brit… Wow, were were really such utter bastards to the Indians when the country was a colony? I was under the impression it was all tea and cricket. But the British, as depicted here, appear largely to be working entirely for the East Indian company, treating the local population with, at best, disdain, and often brutality. All the while, seeking to manipulate local politics (with, it must be said, the help of some Indians) to their own advantage. After 70 episodes of this, such is the guilt, I can barely enjoy my chicken tikka masala without giving it reparations.

Not for the show, I should stress. But as a Brit… Wow, were were really such utter bastards to the Indians when the country was a colony? I was under the impression it was all tea and cricket. But the British, as depicted here, appear largely to be working entirely for the East Indian company, treating the local population with, at best, disdain, and often brutality. All the while, seeking to manipulate local politics (with, it must be said, the help of some Indians) to their own advantage. After 70 episodes of this, such is the guilt, I can barely enjoy my chicken tikka masala without giving it reparations.

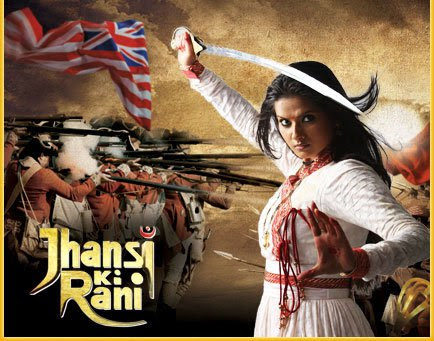

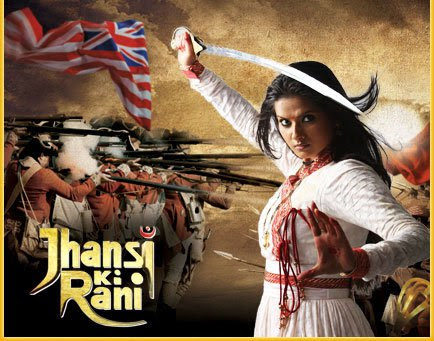

I say 70 episodes, but the entire series is considerably longer. Wikipedia lists it as 408, but those are apparently 25-minute shows. Netflix seems to have doubled it up (bringing its length into line with the more traditional Hispanic telenovelas which I’ve previously reviewed). Yet even allowing for that, to this point they only seem to have about 30% of the show. They also shortened the title from its full name, Ek Veer Stree Ki Kahaani… Jhansi Ki Rani, which translates as Story of a Brave Woman… The Queen of Jhansi.

Simply based on the level of intrigue here, this feels like an Indian version of Game of Thrones. Albeit without the incest. Or the dragons. Or the budget. And is based on a real character, Lakshmibai. But it’s quite easy also to draw a line between Arya Stark and the teenage heroine here, Manikarnika (Gupta) a.k.a. Manu, neither caring one bit for ‘traditional’ behaviour. Manu, in particular, objects to the occupying British forces and their disrespectful treatment of the native population. So she crafts a secret identity, Kranti Guru, and uses this to fight back against the Brits, even (gasp!) desecrating the Union Jack. She’s helped by her mentor, Tatya Tope, who occasionally dons the mask as well, when necessary.

However, a literally stellar horoscope leads to Manu being betrothed to the Maharaja of Jhansi, Gangadhar Rao (Dharmadhikari). And this is my biggest issue. Cultural differences be damned, there is no way in which a prepubescent girl marrying a middle-aged man can seem appropriate, or other than incredibly creepy. Manu gets her first period in one of the final episodes, and the reaction of everyone can be summarised as, “Good, now you can give the king a heir.” [The reality was slightly less creepy: Lakshmibai did, indeed, marry the king at age 13. However, they didn’t have a son until she was in her twenties]

The British – already unhappy with Manu’s rebellious outbursts – are far from happy at the prospect of her marrying Gangadhar and continuing the line. Even before she arrives at the palace, there are backroom conspiracies involving some of his relatives (not least his own mother), who ally themselves with the colonialists for their mutual benefit. These schemes go up to and include multiple assassination plots against the king, and indeed, his bride-to-be. Time for Kranti Guru to come out again, particularly to face off against gold-toothed British psychopath Marshall (Verma). His relentless pursuit, without regard for who gets hurt, earns him Manu’s undying enmity. [Weirdly, he’s played by an Indian actor in “white face”, as are some – but not all – of the other English officers, some of whom are dubbed.]

The British – already unhappy with Manu’s rebellious outbursts – are far from happy at the prospect of her marrying Gangadhar and continuing the line. Even before she arrives at the palace, there are backroom conspiracies involving some of his relatives (not least his own mother), who ally themselves with the colonialists for their mutual benefit. These schemes go up to and include multiple assassination plots against the king, and indeed, his bride-to-be. Time for Kranti Guru to come out again, particularly to face off against gold-toothed British psychopath Marshall (Verma). His relentless pursuit, without regard for who gets hurt, earns him Manu’s undying enmity. [Weirdly, he’s played by an Indian actor in “white face”, as are some – but not all – of the other English officers, some of whom are dubbed.]

To be honest, Manu’s action scenes are a bit crap, mostly consisting of her waving a sword around in severely choreographed battles. She’d last about two minutes against other teenage warrioresses, like Hanna or Hit-Girl. Still, she has a certain charm, not least for her razor-sharp intellect, which lets her argue with – and usually kick the mental ass of – religious scholars, politicians and the king. She also has an unshakeable faith that everyone is redeemable, and more than once, turns enemies into loyal allies. Most notable is dacoit (bandit) Samar Singh, initially hired to murder Manu. When the tables are turned, and she forgives him, he abandons his life of crime. That’s the level of devotion she inspires.

Run away, foreigner, run away!

This brave Manu riding the horse is Lakshmi Bai

Fire will rain on you, now you are doomed.

Look at the colourful India, India will defeat you.

She has come to claim your head, the Queen of Jhansi has come.

Run away foreigner, the Queen of Jhansi has come!

Despite its origins, there are no song-and-dance numbers, though the music still plays a significant, if repetitive part. The song quoted above shows up in every other episode, and the re-use of certain cues could be turned into a drinking game, e.g. take a shot every time that “sad trombone”-like arpeggio sting is heard. However, the most defining style element is the reaction shot. It seems nothing dramatic can happen without everyone present in the scene subsequently being ready for their close-up – sometimes multiple times. And considering how often such moments happen in the king’s court… it takes a while. This does lighten the intellectual burden required to keep up. Chris was usually present for only about one-third of the screen time each day, yet she was able to hang in there, with only minor explanations from me.

For the great majority of the time, it’s light stuff, with Manu escaping every pitfall her enemies set for her. Then, the hammer drops: to extend the GoT comparison, it’s the Rani equivalent of the Red Wedding. Fewer bodies, to be sure – just one – yet the resulting emotional wallop was still brutal, sending me through multiple stages of grief during the subsequent fall-out. “No… Surely they haven’t… It’s got to be a dream sequence.” All told, it was easily the most impactful death in any of the telenovelas I’ve watched, regardless of their origin, and the repercussions ran on for multiple episodes. As do the reaction shots. So. Many. Reaction. Shots.

For the great majority of the time, it’s light stuff, with Manu escaping every pitfall her enemies set for her. Then, the hammer drops: to extend the GoT comparison, it’s the Rani equivalent of the Red Wedding. Fewer bodies, to be sure – just one – yet the resulting emotional wallop was still brutal, sending me through multiple stages of grief during the subsequent fall-out. “No… Surely they haven’t… It’s got to be a dream sequence.” All told, it was easily the most impactful death in any of the telenovelas I’ve watched, regardless of their origin, and the repercussions ran on for multiple episodes. As do the reaction shots. So. Many. Reaction. Shots.

I wonder if the 70-episode cutoff point was chosen by Netflix, being the point at which Manu “grows up”. It appears she is played by an older actress (right) in the latter stages of the series. As it stands, however, it’s an interesting approach to have a series apparently aimed at adults, with a 14-year-old character as the lead. While I can’t say it was wholly successful, it proved a remarkably easy watch, and I was genuinely sorry when I ran out of episodes.

Creative Director: Sujata Rao

Star: Ulka Gupta, Sameer Dharmadhikari, Vikas Verma, Ashnoor Kaur

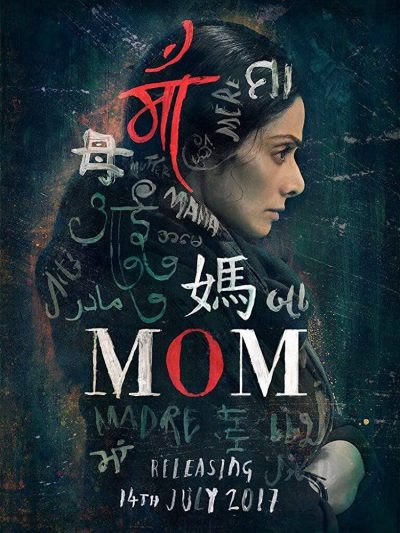

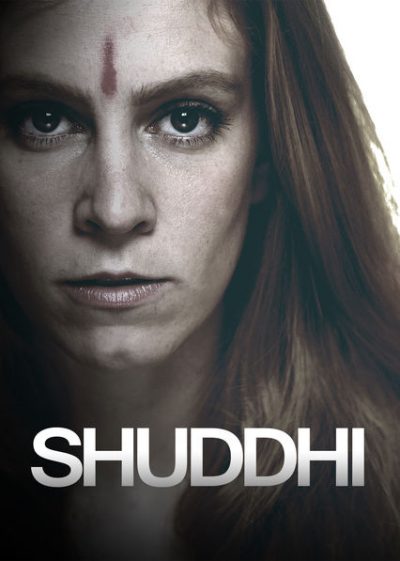

This strong Indian tale of revenge and (step)mother love was, sadly, the last major appearance for its star. Sridevi accidentally drowned in a Dubai hotel, a few months after the film was released. But it’s a wonderful monument to her talent. She plays Devki Sabarwal, a biology teacher who is having trouble in the relationship with her teenage step-daugher, Arya (Ali). But everything changes after Arya is abducted while leaving a party, raped and beaten, then thrown into a roadside ditch. The fact Arya had been drinking is used to discredit her testimony, and the absence of forensic evidence helps her attackers walk free. Blood relation or not, Devki isn’t having that. With the help of private eye DK (Siddiqui), she starts to impose her own kind of justice, despite the increasing suspicions of Detective Francis (Khanna).

This strong Indian tale of revenge and (step)mother love was, sadly, the last major appearance for its star. Sridevi accidentally drowned in a Dubai hotel, a few months after the film was released. But it’s a wonderful monument to her talent. She plays Devki Sabarwal, a biology teacher who is having trouble in the relationship with her teenage step-daugher, Arya (Ali). But everything changes after Arya is abducted while leaving a party, raped and beaten, then thrown into a roadside ditch. The fact Arya had been drinking is used to discredit her testimony, and the absence of forensic evidence helps her attackers walk free. Blood relation or not, Devki isn’t having that. With the help of private eye DK (Siddiqui), she starts to impose her own kind of justice, despite the increasing suspicions of Detective Francis (Khanna).

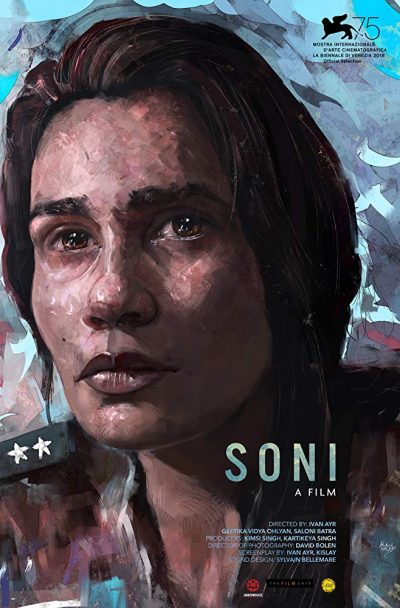

This takes place in the Indian city of Delhi, and despite the title and the poster, is really about two policewomen, almost equally. Title billing goes to Soni (Ohlyan), a young officer who is coming to terms with life after divorce from her husband, Naveen (Shukla). She is also the possessor of a fierce temper, which repeatedly gets her into trouble because she’s unable to keep her cool with suspects. Forced to play clean-up is her boss, superintendent Kalpana Ummat (Batra), who seems to see something of her younger self in Soni, as well as appreciating the junior cop’s potential. But there’s only so far she can protect Soni from the consequences of her outbursts.

This takes place in the Indian city of Delhi, and despite the title and the poster, is really about two policewomen, almost equally. Title billing goes to Soni (Ohlyan), a young officer who is coming to terms with life after divorce from her husband, Naveen (Shukla). She is also the possessor of a fierce temper, which repeatedly gets her into trouble because she’s unable to keep her cool with suspects. Forced to play clean-up is her boss, superintendent Kalpana Ummat (Batra), who seems to see something of her younger self in Soni, as well as appreciating the junior cop’s potential. But there’s only so far she can protect Soni from the consequences of her outbursts. Not unlike the saga of

Not unlike the saga of  I should probably start by providing some background the film omits – likely because the intended Indian audience were well aware of it. In 2012, a notorious gang-rape took place in Delhi, the victim subsequently dying. Of the six attackers, four were sentenced to death and one committed suicide in prison – but the sixth, being a juvenile, could only receive a maximum sentence of three years. This loophole appalled many, including two journalists depicted in this film, Jyothi (Nivedhitha) and Divya (Karagada), who begin a campaign to revise the law.

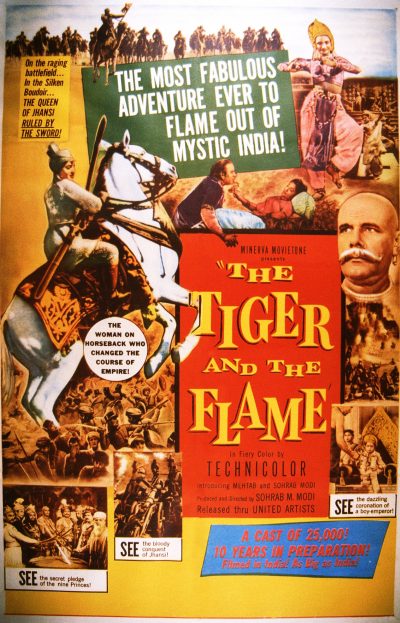

I should probably start by providing some background the film omits – likely because the intended Indian audience were well aware of it. In 2012, a notorious gang-rape took place in Delhi, the victim subsequently dying. Of the six attackers, four were sentenced to death and one committed suicide in prison – but the sixth, being a juvenile, could only receive a maximum sentence of three years. This loophole appalled many, including two journalists depicted in this film, Jyothi (Nivedhitha) and Divya (Karagada), who begin a campaign to revise the law. The movie opens with a particularly elaborate disclaimer, admitting that “certain cinematic liberties have been sought,” and that “this film does not claim historical authenticity.” Probably wise: Indians take their national heroes very seriously; just last year, another historical epic, Padmaavat,

The movie opens with a particularly elaborate disclaimer, admitting that “certain cinematic liberties have been sought,” and that “this film does not claim historical authenticity.” Probably wise: Indians take their national heroes very seriously; just last year, another historical epic, Padmaavat,  Not for the show, I should stress. But as a Brit… Wow, were were really such utter bastards to the Indians when the country was a colony? I was under the impression it was all tea and cricket. But the British, as depicted here, appear largely to be working entirely for the East Indian company, treating the local population with, at best, disdain, and often brutality. All the while, seeking to manipulate local politics (with, it must be said, the help of some Indians) to their own advantage. After 70 episodes of this, such is the guilt, I can barely enjoy my chicken tikka masala without giving it reparations.

Not for the show, I should stress. But as a Brit… Wow, were were really such utter bastards to the Indians when the country was a colony? I was under the impression it was all tea and cricket. But the British, as depicted here, appear largely to be working entirely for the East Indian company, treating the local population with, at best, disdain, and often brutality. All the while, seeking to manipulate local politics (with, it must be said, the help of some Indians) to their own advantage. After 70 episodes of this, such is the guilt, I can barely enjoy my chicken tikka masala without giving it reparations. The British – already unhappy with Manu’s rebellious outbursts – are far from happy at the prospect of her marrying Gangadhar and continuing the line. Even before she arrives at the palace, there are backroom conspiracies involving some of his relatives (not least his own mother), who ally themselves with the colonialists for their mutual benefit. These schemes go up to and include multiple assassination plots against the king, and indeed, his bride-to-be. Time for Kranti Guru to come out again, particularly to face off against gold-toothed British psychopath Marshall (Verma). His relentless pursuit, without regard for who gets hurt, earns him Manu’s undying enmity. [Weirdly, he’s played by an Indian actor in “white face”, as are some – but not all – of the other English officers, some of whom are dubbed.]

The British – already unhappy with Manu’s rebellious outbursts – are far from happy at the prospect of her marrying Gangadhar and continuing the line. Even before she arrives at the palace, there are backroom conspiracies involving some of his relatives (not least his own mother), who ally themselves with the colonialists for their mutual benefit. These schemes go up to and include multiple assassination plots against the king, and indeed, his bride-to-be. Time for Kranti Guru to come out again, particularly to face off against gold-toothed British psychopath Marshall (Verma). His relentless pursuit, without regard for who gets hurt, earns him Manu’s undying enmity. [Weirdly, he’s played by an Indian actor in “white face”, as are some – but not all – of the other English officers, some of whom are dubbed.] For the great majority of the time, it’s light stuff, with Manu escaping every pitfall her enemies set for her. Then, the hammer drops: to extend the GoT comparison, it’s the Rani equivalent of the Red Wedding. Fewer bodies, to be sure – just one – yet the resulting emotional wallop was still brutal, sending me through multiple stages of grief during the subsequent fall-out. “No… Surely they haven’t… It’s got to be a dream sequence.” All told, it was easily the most impactful death in any of the telenovelas I’ve watched, regardless of their origin, and the repercussions ran on for multiple episodes. As do the reaction shots. So. Many. Reaction. Shots.

For the great majority of the time, it’s light stuff, with Manu escaping every pitfall her enemies set for her. Then, the hammer drops: to extend the GoT comparison, it’s the Rani equivalent of the Red Wedding. Fewer bodies, to be sure – just one – yet the resulting emotional wallop was still brutal, sending me through multiple stages of grief during the subsequent fall-out. “No… Surely they haven’t… It’s got to be a dream sequence.” All told, it was easily the most impactful death in any of the telenovelas I’ve watched, regardless of their origin, and the repercussions ran on for multiple episodes. As do the reaction shots. So. Many. Reaction. Shots.

Officer Shivani Shivaji Roy (Mukerji) is part of the Serious Crimes Squad in Delhi, whose approach to policing is very much “by any means necessary.” However, she is taken out of her area of expertise when Pyaari. a young girl she has been helping goes missing from an orphanage. Everything indicates the girl has been picked up by a sex trafficking ring, run by Sunny Katyal (Verma) and his partner, Karan (Bhasin), and will soon be sold off to the highest bidder and exported out of the country. Roy has to work her way up the chain to rescue Pyaari, despite opposition both from her boss, because it’s not her responsibility, and from the gang. As she gets nearer to the top, the climb becomes increasingly hard, with the criminals making it clear they won’t take lightly the threat to their lucrative business which Roy represents. It’s also clear they have friends in high places.

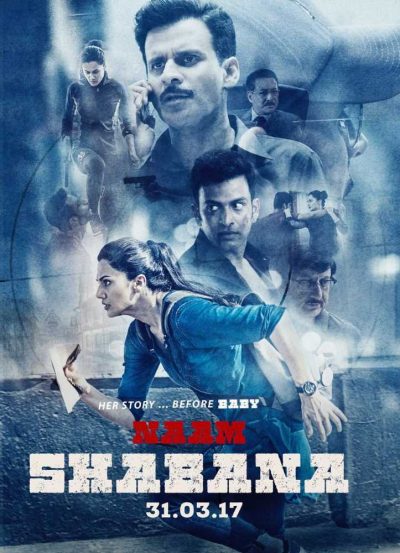

Officer Shivani Shivaji Roy (Mukerji) is part of the Serious Crimes Squad in Delhi, whose approach to policing is very much “by any means necessary.” However, she is taken out of her area of expertise when Pyaari. a young girl she has been helping goes missing from an orphanage. Everything indicates the girl has been picked up by a sex trafficking ring, run by Sunny Katyal (Verma) and his partner, Karan (Bhasin), and will soon be sold off to the highest bidder and exported out of the country. Roy has to work her way up the chain to rescue Pyaari, despite opposition both from her boss, because it’s not her responsibility, and from the gang. As she gets nearer to the top, the climb becomes increasingly hard, with the criminals making it clear they won’t take lightly the threat to their lucrative business which Roy represents. It’s also clear they have friends in high places. If you took four different films, by four different directors, and edited them together into a single entity, you might end up something similar to this. Oh, make no mistake: I still enjoyed most of this. It just doesn’t feel like a coherent whole, perhaps because it is a spin-off involving some of the same characters from an earlier film, Baby. For at least three-quarters of it, however, not having seen its predecessor shouldn’t be too much of a problem.

If you took four different films, by four different directors, and edited them together into a single entity, you might end up something similar to this. Oh, make no mistake: I still enjoyed most of this. It just doesn’t feel like a coherent whole, perhaps because it is a spin-off involving some of the same characters from an earlier film, Baby. For at least three-quarters of it, however, not having seen its predecessor shouldn’t be too much of a problem.

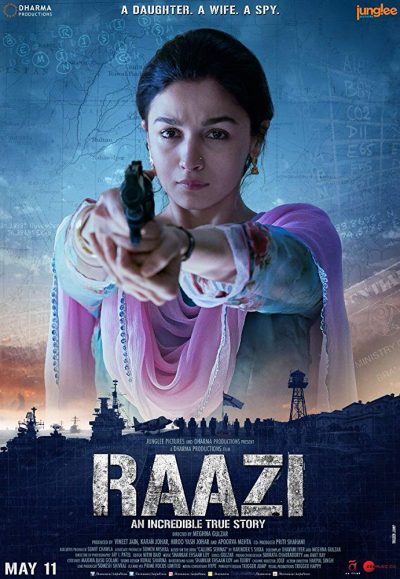

This Indian spy thriller manages to be both remarkably restrained and human, avoiding a potentially jingoistic approach, and going for something considerably more measured. It takes place just before the war between India and Pakistan in 1971, when Indian agent Hidayat Khan is pretending to give information to Pakistan. In order to get close to their top brass, he convinces his daughter, Sehmat (Bhatt), to enter an arranged marriage to Iqbal Syed (Ahlawat), an officer whose father (Sharma) is a Brigadier in the Pakistani army. After being trained by senior intelligence officer Khalid Mir (Kaushal), she goes to join her new husband, and begins operations as a spy inside the Brigadier’s household.

This Indian spy thriller manages to be both remarkably restrained and human, avoiding a potentially jingoistic approach, and going for something considerably more measured. It takes place just before the war between India and Pakistan in 1971, when Indian agent Hidayat Khan is pretending to give information to Pakistan. In order to get close to their top brass, he convinces his daughter, Sehmat (Bhatt), to enter an arranged marriage to Iqbal Syed (Ahlawat), an officer whose father (Sharma) is a Brigadier in the Pakistani army. After being trained by senior intelligence officer Khalid Mir (Kaushal), she goes to join her new husband, and begins operations as a spy inside the Brigadier’s household.