“Being young, vigorous, and not afraid to show herself to the multitude, she gained a great influence over the hearts of the people. It was this influence, this force of character, added to a splendid and inspiring courage, that enabled her to offer a desperate resistance to the British…. Whatever her faults in British eyes may have been, her countrymen will ever believe that she was driven by ill-treatment into rebellion; that her cause was a righteous cause. To them she will always be a heroine.”

— “History of the Indian Mutiny” by Sir John Kaye and Colonel George Malleson

The notion of a warrior woman, who leads the fight against occupying forces is something which quite a common trope of legend and lore worldwide. The family tree includes the likes of Boudicaa in Roman England, through Vietnam’s Trung Sisters, Martha Christina Tiahahu of Indonesia – and, of course, Joan of Arc in France.

The notion of a warrior woman, who leads the fight against occupying forces is something which quite a common trope of legend and lore worldwide. The family tree includes the likes of Boudicaa in Roman England, through Vietnam’s Trung Sisters, Martha Christina Tiahahu of Indonesia – and, of course, Joan of Arc in France.

Lakshmibai is far from unique in Indian history as a warrior woman. The line probably starts with Rudrama Devi, who reigned in her own right over the Kakatiya kingdom for three decades during the late 13th century. In terms of rebellion against the British, who began occupying parts of India from around 1757, Lakshmibai was preceded by Rani Velu Nachiyar. After Nachiyar’s husband was killed in 1772, she raised an army and allied with other monarchs to fight the British.

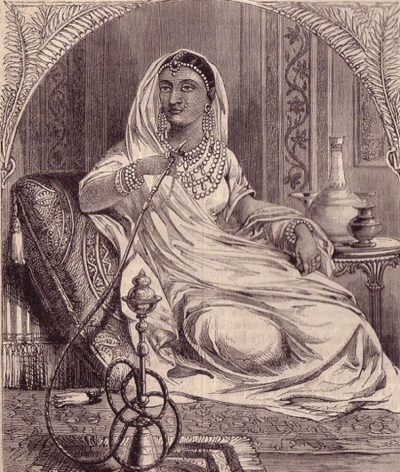

Half a century later, in 1828, Manikarnika Tambe was born – the girl who would become Rani Lakshmibai. Her mother died when Manu, as she was known, was still a toddler. She was therefore brought up more by her father, who worked for local ruler Baji Rao II. This may explain why her upbringing was non-traditional, Manu learning how to wield a sword, as well as archery and horsemanship. But barely after becoming a teenager, at the age of 13, she was married to the Maharaja of Jhansi, Raja Gangadhar Newalkar. As was tradition, she took a new name: Lakshmibai, in honour of the Hindu goddess of wealth, fortune and prosperity, Lakshmi.

She was not able to provide him with a heir, their only child dying while only a few months old. Instead, shortly before the Maharaja’s death in 1853, they adopted a son. And that’s where Lakshmibai’s problems with the British started. For the British East India Company refused to recognize the adopted son as heir to the throne, applying what was called the ‘Doctrine of Lapse’ and annexing the state of Jhansi to its territories. The following year, Lakshmibai was literally pensioned off, being given a stipend and ordered to leave the palace. Despite this, she does not seem to have initially harboured strong anti-British feelings at this point.

“Her two qualities worth mentioning are her bravery and her generosity. Mostly, she was dressed in male attire. She used to wear a pajama with a vest of dark purple colour. On her head, she wore a turban like cap. On her waist would be a duppatta-like cloth in which a sword would be tucked.”

— Vishnubhat Godse

In June 1857, rebel soldiers seized the fort at Jhansi and massacred, not only the officers garrisoned there, but their families. After the rebels left, Lakshmibai took over, running Jhansi on behalf of the British until they could send a superintendent. That’s not exactly Joan of Arc-like… Instead, she fought off efforts by the rebels to claim the Jhansi throne for her husband’s nephew, as well as an attempted invasion by neighbouring states. It’s possible the latter enemy’s alliance with the British helped sour relations between them and Lakshmibai, though she still seems to have intended to act as a caretaker to this point.

In June 1857, rebel soldiers seized the fort at Jhansi and massacred, not only the officers garrisoned there, but their families. After the rebels left, Lakshmibai took over, running Jhansi on behalf of the British until they could send a superintendent. That’s not exactly Joan of Arc-like… Instead, she fought off efforts by the rebels to claim the Jhansi throne for her husband’s nephew, as well as an attempted invasion by neighbouring states. It’s possible the latter enemy’s alliance with the British helped sour relations between them and Lakshmibai, though she still seems to have intended to act as a caretaker to this point.

But clearly something changed her mind. For when the British eventually showed up, in March 1858, she declined to hand over the fort, instead issuing a proclamation: “We fight for independence. In the words of Lord Krishna, we will if we are victorious, enjoy the fruits of victory, if defeated and killed on the field of battle, we shall surely earn eternal glory and salvation.” Brave words, though with hindsight, basically saying, “Come and have a go if you think you’re hard enough,” to the British, at the point of basically peak Empire, might not have been the wisest of tactics…

The British laid siege to Jhansi, and the last hope of rescue ended when an approaching force of 20,000 supporters, under the command of Lakshmibai’s childhood friend, Tatya Tope, was headed off and beaten at the Battle of Betwa River. After ten days, the walls were breached, and the British entered. There is some debate over what happened to the civilian population thereafter. Some reports indicate all were massacred, but Brahmin priest Vishnubhat Godse gave an eye-witness account which said, “All men between the ages of five to thirty were searched out and killed… But the British did not kill women; they stood at a distance from women and told them to hand over whatever gold and jewellery they were wearing.”

Legend states that the queen leapt from the fort on a horse, with her adopted son strapped to her back. Godse’s account is slightly tamer: “She wore male attire, riding shoes and armour covering her whole body. She did not carry even a paisa coin on herself. With a resounding ‘Jai Shankar’ war cry, she descended from the fort and, crossing the city, went out through the north gate. The Company cavalry chased them for about a kos and a half (3 miles). Thereafter, [Lakshmibai]’s horses were no longer in sight.” She regrouped with the remnants of Tatya Tope’s forces, but they were again beaten by Imperial forces, and forced to flee once again.

Two months later, on June 17, she fought her final battle, her army going up against the 8th King’s Royal Irish Hussars. Again, what exactly happened to Lakshmibai has been clouded through the mists of time and folklore. One story says she dressed as a cavalry officer and attacked the hussars; unhorsed, she was wounded, but fought on, firing at her opponent with a pistol, before being shot by his rifle. Godse’s account is almost terse, saying she was “wounded by a bullet, but she continued to fight. Just then, her thigh was wounded with a sword and she fell off the horse. Tatya Tope rushed forward and held her dead body.”

“The high descent of the Rani, her unbounded liberality to her troops and retainers, and her fortitude, which no reverses could shake, rendered her an influential and dangerous adversary.”

— Sir Hugh Rose

Her post-rebellion legacy was a complex one. Some English writers maligned Lakshmibai, blaming her for the massacre by the rebels at Jhansi – in particular army doctor, Thomas Lowe, who called the queen the “Jezebel of India.” However, Sir Hugh Rose, commander of the British forces who took Jhansi spoke of her in much kinder terms, calling her “Personable, clever and beautiful,” “The most dangerous of all Indian leaders,” and “The bravest and best military leader of the rebels”.

Her post-rebellion legacy was a complex one. Some English writers maligned Lakshmibai, blaming her for the massacre by the rebels at Jhansi – in particular army doctor, Thomas Lowe, who called the queen the “Jezebel of India.” However, Sir Hugh Rose, commander of the British forces who took Jhansi spoke of her in much kinder terms, calling her “Personable, clever and beautiful,” “The most dangerous of all Indian leaders,” and “The bravest and best military leader of the rebels”.

She became a character in a number of English novels, such as The Rane: A Legend of the Indian Mutiny written in 1887 under the pseudonym of “Gillean”, by British officer John Maclean. In it, she seduces an agent of the empire, reinforcing Lowe’s negative depiction. Yet others were more sympathetic, such as Michael White’s Lachmi Bai, Rani of Jhansi, published in 1901. For example, that version of her story absolves Lakshmibai of responsibility for the rebel massacre, blaming a treacherous Muslim associate instead.

In India, of course, there is no such divergence, and she is revered to this day. There are many statues of her, typically on horseback with her son on her back, as the stories depict. She has been honoured in poem and song, and multiple films and TV series. The first was 1953’s Jhansi Ki Rani, released in an English dub three years later as The Tiger and the Flame. The first Technicolor film to be made in India, it was also the most expensive Hindi film made to that point. The makers brought in talent from Hollywood, such as Ernest Haller, Oscar-winning cinematographer for Gone With The Wind, and editor Russell Lloyd, who had also worked with Vivien Leigh, on Anna Karenina in 1948. However, this version proved to be a flop at the box-office.

There have been three television series and two further movies based on the life of the queen. [Some of these adaptations and versions will be reviewed here shortly, and will be listed below] Still to come, and potentially the biggest in the West, is The Warrior Queen of Jhansi, originally titled Swords and Sceptres. In this, Devika Bhise (shown above right) plays Lakshmibai, with Rupert Everett as Sir Hugh Rose, and the supporting cast including Ben Lamb, Derek Jacobi and Jodhi Ma. This picked up distribution through Roadside Attractions in June, and is supposedly scheduled for a fall 2019 release – though no date has been fixed as yet. I’m curious to see how it performs, and if it will help Lakshmibai become as familiar an icon here, as she is in India.