Literary rating: ★★★★

Kick-butt quotient: Variable

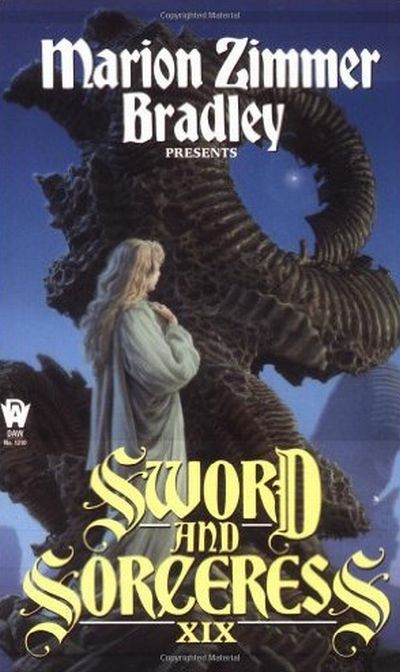

Although the late Bradley (d. 1999) is credited as “editor” of this volume of the series, it’s really the second of three that were made from the pile of manuscripts submitted before her death, and actually edited by her sister-in-law, Elisabeth Waters. It continues a trend I noticed in Sword and Sorceress XVII,: much more emphasis on the sorcery half of the sword-and-sorcery equation. Out of 25 tales here, 20 have heroines who are magic users; only six feature swordswomen (one protagonist is both), and two of the latter don’t do any actual fighting in their stories. (Of course, magic-wielding heroines may be fighters too, in their own way!) Other trends that I noticed here were a number of stories treating real-world or imagined pagan pantheons as real, frequent use of various historic world cultures (ancient Egypt, the Hellenistic world, 10th-century Britain, etc.) as settings or models for invented settings, and several coming-of-age stories. While I enjoyed the vast majority of the selections here, I felt that this volume didn’t have as high a number of really outstanding stories as previous series volumes that I’ve read, so it’s the first of the latter not to get five stars from me. (But four is still a high rating!) Five of the writers represented are males, about the average proportion for this series.

Although the late Bradley (d. 1999) is credited as “editor” of this volume of the series, it’s really the second of three that were made from the pile of manuscripts submitted before her death, and actually edited by her sister-in-law, Elisabeth Waters. It continues a trend I noticed in Sword and Sorceress XVII,: much more emphasis on the sorcery half of the sword-and-sorcery equation. Out of 25 tales here, 20 have heroines who are magic users; only six feature swordswomen (one protagonist is both), and two of the latter don’t do any actual fighting in their stories. (Of course, magic-wielding heroines may be fighters too, in their own way!) Other trends that I noticed here were a number of stories treating real-world or imagined pagan pantheons as real, frequent use of various historic world cultures (ancient Egypt, the Hellenistic world, 10th-century Britain, etc.) as settings or models for invented settings, and several coming-of-age stories. While I enjoyed the vast majority of the selections here, I felt that this volume didn’t have as high a number of really outstanding stories as previous series volumes that I’ve read, so it’s the first of the latter not to get five stars from me. (But four is still a high rating!) Five of the writers represented are males, about the average proportion for this series.

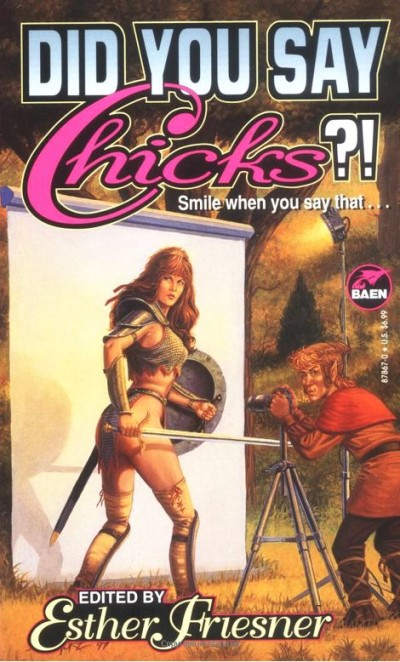

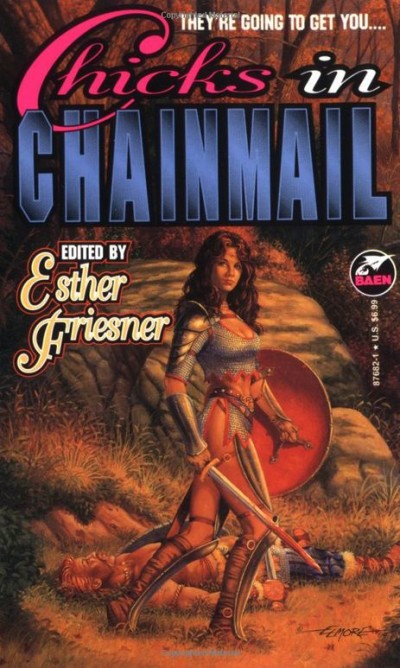

Bradley had instituted a by-invitation-only policy for submissions before she died, but had invited everyone who’d previously contributed to the series. So all of the contributors here have been represented in previous volumes, though some are new to me (I haven’t read all of the previous numbers) and some who aren’t are writers whose names I’ve forgotten. Those whose work I’ve definitely read before include Diana Paxson, Esther Friesner, Bunnie Bessel, and Dorothy Heydt (whose daughter also has a story here).

When I encountered Heydt’s ancient Greek sorceress, Cynthia, in Sword and Sorceress XVII, I made the comment in my review that she might be a series character. That’s confirmed here in “Lord of the Earth;” but that story has so much allusion to back-story that it loses a lot for readers who haven’t followed the character through the whole story cycle. Paxson’s “The Sign of the Boar” is a sequel to “Lady of Flame” from the same earlier volume; but here, her considerable talent is disappointingly wasted on a story mainly intended to disparage Christians. “A Simple Spell” by Marilyn A. Racette is a very slight story, which (at least for this reader) failed to make much impression. In her brief intro to A. Hall’s “Sylvia,” Waters notes that she wanted to close the volume with something “short and funny.” It’s quite short, and has a mordant black humor in its conclusion; but it’s really more tragic than funny if you think about it (and definitely makes the point that, when you try to gain your ends by sneaky and manipulative means instead of honesty, the results may not be what you bargained for).

Those are the weaker stories, but I’d rate all of the rest with at least three stars, and often more. Set in a land ruled by queens chosen by a magic-endued sword, Bessel’s “Sword of Queens” is the one five-star work here; it has the emotional and psychological complexity and power of the series’ best tales. Laura J. Underwood’s Scottish-flavored “The Curse of Ardal Glen” is a standout among the serious stories, and Aimee Kratts “One in Ten Thousand” has both an unusual setting (ancient Egypt) and a very original magic system.

Humorous fantasy is represented here fairly often. “Pride, Prejudice and Paranoia’ by Michael Spence is perhaps the best of these; it’s a sequel to “Salt and Sorcery,” which he co-wrote with Waters for an earlier volume, and is set in a magic school (despite the title, it’s set in the present, not Regency England). It would be most appreciated by those who’ve read the first story (which I haven’t, but want to!), but can delight even those that haven’t. The evocation of a graduate school environment is spot-on (Spence was a seminary student when he wrote it), the family dynamics are precious, and there’s a good, subtle message. “A Little Magic” by P. E. (Patricia Elizabeth) Cunningham and “Eloma’s Second Career” by Lorie Calkins are also fine examples of fantasy in a humorous vein; the latter will be especially appealing to ladies of a certain age whose family is raised and who are ready to take on new challenges instead of sitting around and vegetating. (Though their new challenges probably won’t include training to be a sorceress.)

Not a humorous tale, Deborah Burros dark “Artistic License” also deserves mention; it’s a tale of murder and deadly sorcery (but not all murders evoke quite the same moral indignation). This doesn’t mention all of the stories, but at least it should provide prospective readers with something of the flavor of the collection!

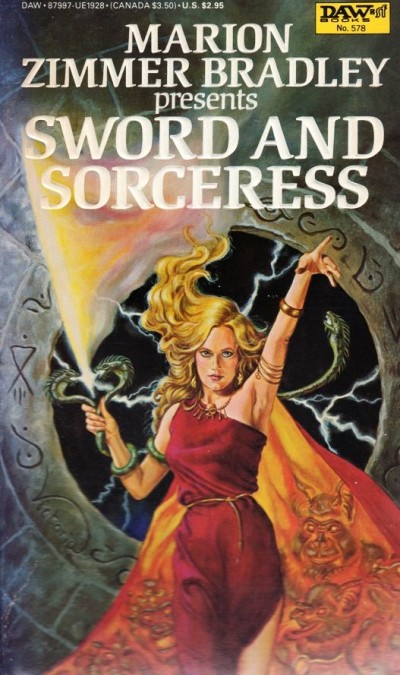

Editors: Marion Zimmer Bradley, Elisabeth Waters

Publisher: DAW, available through Amazon, currently only as a printed book.

A version of this review previously appeared on Goodreads.

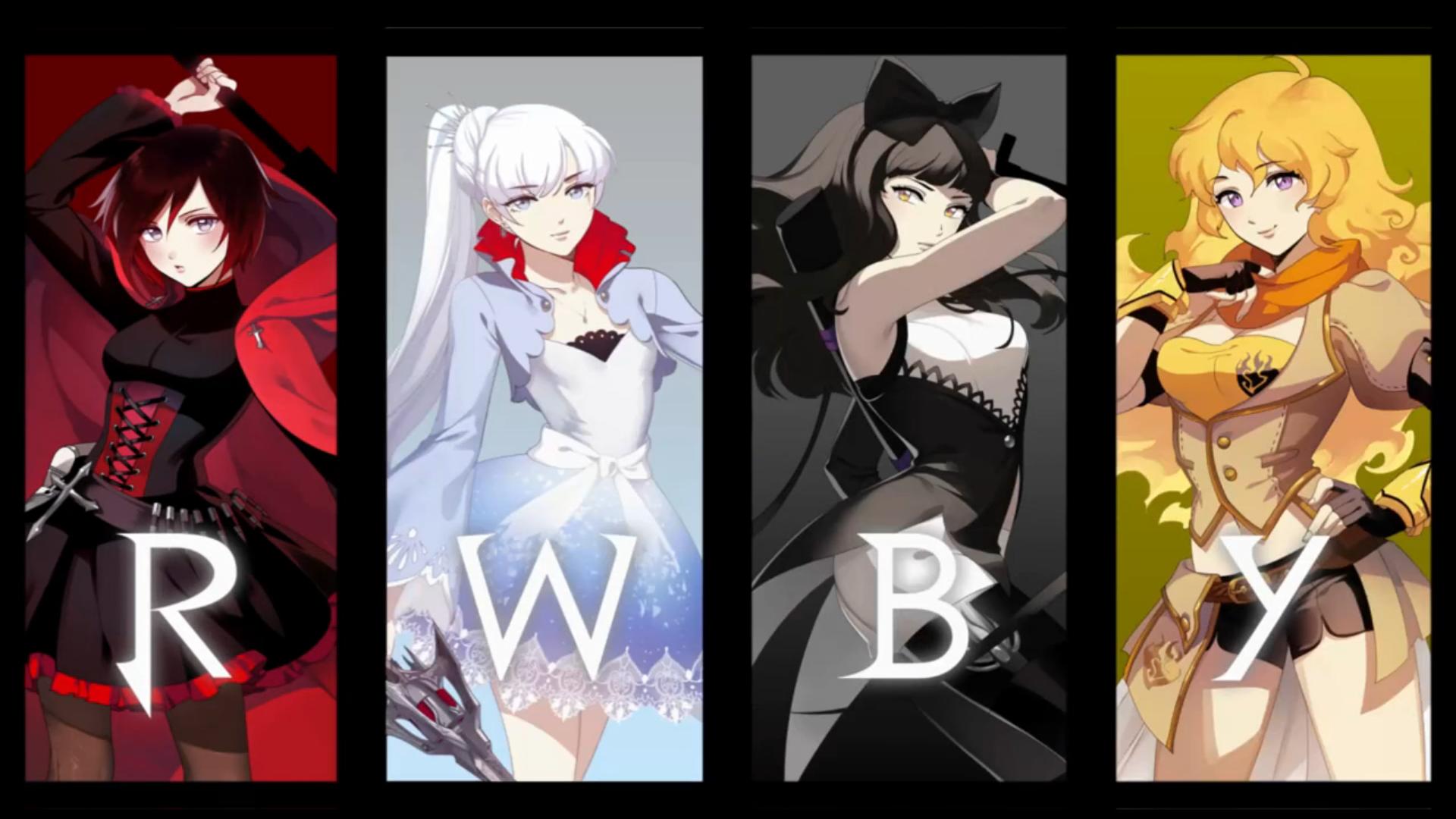

There are occasionally times where our book reviewer Werner’s “split scale” of grades for both artistic merit and action, would come in handy. This is one of those times. For the action scenes here are as glorious as you would expect from the man behind Dead Fantasy, virtuoso symphonies of exquisite hyper-violence, meted out and absorbed by characters and monsters without fear or bias, in ways limited only – and not very much, at that – by the creator’s imagination. Probably inevitably, this overshadows a fairly perfunctory plot, and characters whose characterization is largely defined by the shade they wear. On a split scale, this would merit five stars for both the quantity and quality of action, but likely three or three and a half for artistic merit.

There are occasionally times where our book reviewer Werner’s “split scale” of grades for both artistic merit and action, would come in handy. This is one of those times. For the action scenes here are as glorious as you would expect from the man behind Dead Fantasy, virtuoso symphonies of exquisite hyper-violence, meted out and absorbed by characters and monsters without fear or bias, in ways limited only – and not very much, at that – by the creator’s imagination. Probably inevitably, this overshadows a fairly perfunctory plot, and characters whose characterization is largely defined by the shade they wear. On a split scale, this would merit five stars for both the quantity and quality of action, but likely three or three and a half for artistic merit.