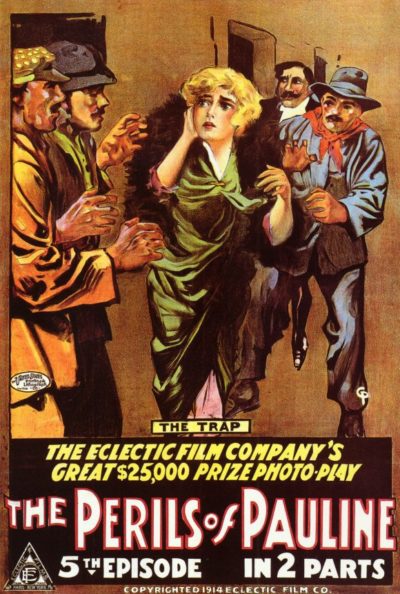

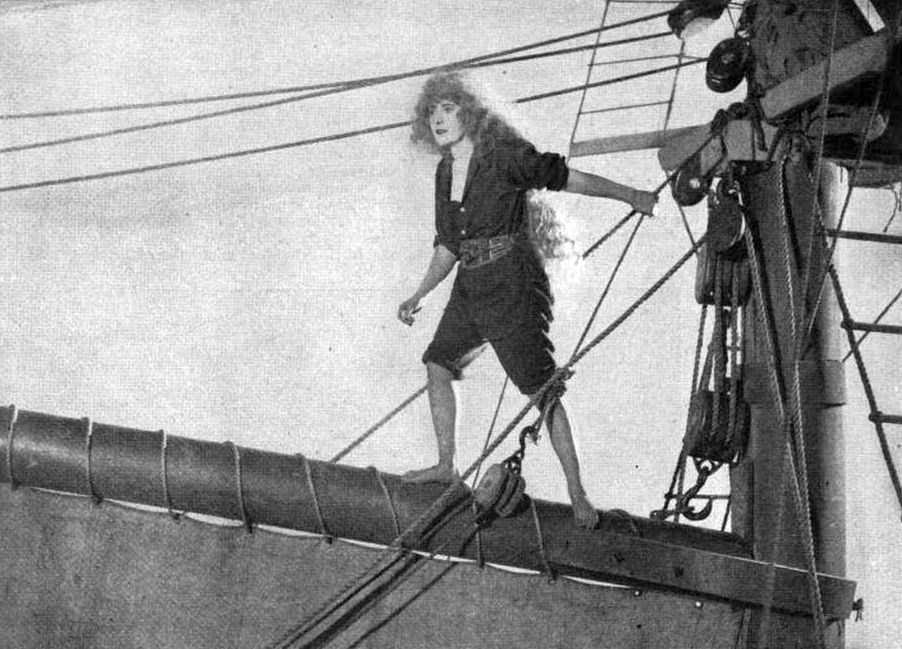

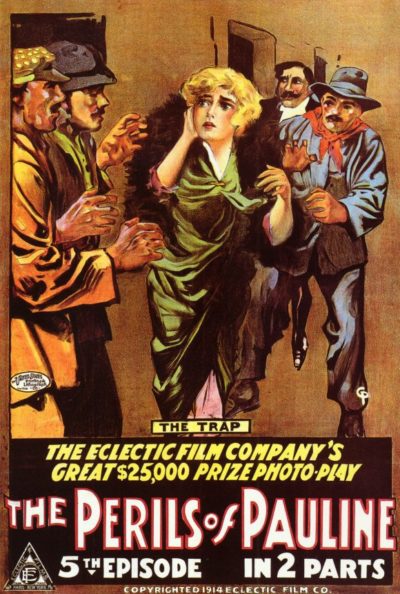

American actress Pearl White was dubbed “Queen of the Serials” for her roles in some of the most popular episodic cinema productions. Beginning in 1914 with The Perils of Pauline, she was a pioneer of action heroine roles, famous for doing her own stunts, regardless of the risk. The following interview with her was originally published in the September 1921 issue of The American magazine, and offers a glimpse into the lost world of movie-making, almost a century ago.

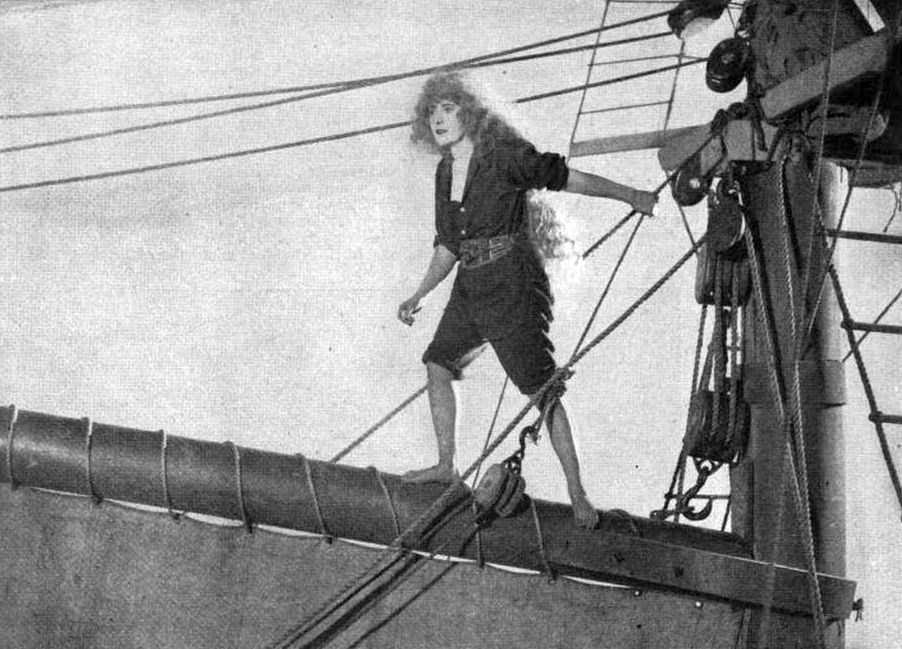

This picture shows Miss White walking the pole at the top of a ship’s mainsail, fifty feet or more above the deck. If she had slipped and fallen, she undoubtedly would have been killed. Once, when she was visiting the battleship “Mississippi,” the sailors begged her to do a “stunt.” Whereupon she climbed to the top of the forward “haystack” mast, the only woman who ever did it on any battleship.

Pearl White’s name is a synonym for courage and daring; yet she says she is “a born coward.”

“I have always been afraid,” she declares; “but I would be ashamed to let fear rule me”

By Mary B. Mullett

Pearl White is one of the most amazing human beings I ever have encountered. As I was leaving her dressing-room at the Fox Film Corporation studios in New York, the man who had arranged the interview asked me what I thought of her. “She’s a wonder!” I said. “Yes,” he agreed. “And the most remarkable thing about her is that she is a living wonder. She has done enough hair-raising stunts to kill half a dozen ordinary girls. Of course, she is doing only regular feature pictures now. No more stunts!… Well—that is—”

He hesitated a moment; then we laughed. No more stunts? That was a joke. She has been in danger over and over again during the past year; and she will keep on doing that sort of thing, because she is “that sort of girl.”

“The perils of Pauline” made Pearl White famous as a “stunt” star. Then came “The Exploits of Elaine,” “The Iron Claw,” “The Fatal Ring,” “The Lightning Raider,” and other serial pictures. All over the world, her name became a synonym for courage and daring.

When we sat down to talk, I looked at her curiously. She has fine dark eyes, sensitive nostrils, an expressive mouth. There isn’t an ounce of superfluous flesh on her body. In manner, she is as frank and unaffected as a boy. In fact, when she was talking about some of her experiences, she often said, “There was another boy in the company” — as if she herself were a boy.

As I thought of the things she has done, they seemed incredible; and I asked the question which millions of persons who have seen her on the screen must have wanted to ask:

“Aren’t you ever afraid?”

“Afraid!” she said. “I’m always afraid! I’ve been afraid all my life!

“I was born in Green Ridge, a little Missouri village which doesn’t exist now. My mother was an Italian and my father was Irish, although he was born in this country. An Irishman, you know. isn’t afraid of the devil himself. But as for my brother and me, we were a beautiful pair of cowards.

“I was afraid of people, afraid of animals, afraid of the dark – afraid of everything! We were the poorest children in town, and that’s saying a good deal. Half of the time I didn’t have any shoes. And because we were poor and because we were cowards, all the other kids picked on us.

“I was afraid of people, afraid of animals, afraid of the dark – afraid of everything! We were the poorest children in town, and that’s saying a good deal. Half of the time I didn’t have any shoes. And because we were poor and because we were cowards, all the other kids picked on us.

“When I was only five years old, I played in ‘Uncle Tom’s Cabin’ with a strolling company that came to the village. Of course the other children wanted to do it, and because I got the chance and they didn’t, they were jealous. So they picked on me all the more. But I was such a coward that I never stood up to them. I’d hit back and then run – with the emphasis on the ‘run’. My brother did the same.

“When my father found this out, he got a strap and told us that if he ever heard of our being beaten by any of the children, or of our running away from them, he would give us an extra whipping himself. He did it too. And soon we learned that it was better to stand up to the children than to take our punishment at home

“When my father found that we were afraid of the dark, he set out to cure us of that too. At night he would send us on errands, each of us in a different direction. Often I’ve had to go half a mile, or more, out on some dark and lonely road. And I couldn’t pretend that I had done it; for he made me go after something which I had to bring back as proof that I really had gone where I was sent. He used to send me to the dark cellar for things, and up0stairs to the dark bedrooms. He meant it all right, but it didn’t cure me. I am still afraid of the dark.”

“And do you mean that now, when you do dangerous stunts for the pictures, you are afraid?” I asked.

“I do mean it!” she said emphatically. “I am petrified with fear. Cold! Frozen! Terrified! I tell you. I’m a coward.”

“Yet you never have someone take your place when there is a particularly dangerous stunt to be dangerous gone through with, do you?”

“You mean, do I ever have anyone ‘double’ for me, as we call it in moving pictures? No, I never have done that.”

“Why not?”

“Well, there’s a sort of fascination about it, for one thing. And after it’s all over, there’s a kind of exhilaration in having done it! I suppose it means more to me because I am afraid. You say to yourself ‘I thought I couldn’t go through with it, but I did!’ And that makes you feel good inside.

“Then, too, you must remember that when I began working in the pictures, I didn’t count for much personally. I wasn’t famous. When I did ‘The Perils of Pauline’ it was the picture that drew. If I broke my neck, or my back, or spoiled my poor face, they could get somebody else. After I had made a reputation, it was different. My name counted then, so then they did want me to have someone double for me in any very dangerous stunts.”

“Why didn’t you do it?”

“Partly from pride and partly because, for some reason, I never seem to get hurt doing the big things.” She rapped on the wooden table beside her. “I’ve done a million stunts. I’ve been hurt over and over again. But” (rap, rap, rap) “it never happened when I was doing what looked really dangerous.

“At least, not since I have been in moving pictures. When I was a young girl, I traveled with the circus for a while doing a trapeze act. Once, when I was hanging by my right hand, the ligaments in my wrist pulled out, and I dropped. I fell on the edge of the net, rolled out of it, came down on my shoulder, and broke my collar bone.

“Once I went into the pictures, my serious injuries have come through some slight mischance; not during a big moment of danger. For instance, in one picture I was bound with ropes, my hands tied behind me, and I was left in the cellar of a building, which was then set on fire. The hero was to rescue me just in the nick of time.

“Everything went smoothly until he tried to carry me up the stairs. I was still bound, and he had thrown me over his shoulder, with my head hanging down his back. He had carried me up six or seven steps when he lost his balance, and toppled over backward. I couldn’t help myself, so I struck on the top of my head, displacing several vertebra.

“Everything went smoothly until he tried to carry me up the stairs. I was still bound, and he had thrown me over his shoulder, with my head hanging down his back. He had carried me up six or seven steps when he lost his balance, and toppled over backward. I couldn’t help myself, so I struck on the top of my head, displacing several vertebra.

“That was the worst hurt I have received. The pain was terrible. For two years I simply lived with osteopaths, and to this day I have some pretty bad times with my back. Yet you wouldn’t have called that a dangerous stunt, or any stunt at all, so far as I was concerned.

“In another picture, I was thrown into the water from a ferryboat just as it was coming into the ferry slip. The slip is enclosed by high walls of solid planking, reaching down into the water, and it would look as if I could not escape being crushed between the boat and the wall of the slip. But at the crucial moment a rope is thrown to me, I catch it, and am pulled out just in time to miss death.

“Well, the program was carried out all right. I was thrown into the water; then, while the ferry—which looked to me as big as the Woolworth Building—came slowly closer, the rope was thrown to me. I had been afraid I would miss it; but I didn’t and they pulled me up onto the dock just in time.

“Then, as I lay there in somebody’s arms, with my eyes closed, I said, ‘Well, boys! I did it! And with that, I threw out my left arm in a gesture which anyone might have made in those circumstances. As I let it drop, my hand went over the side of the dock; and at that moment the ferryboat crashed in, caught my hand, and broke the bones in all the fingers.

“Do you see? The dangerous part of the stunt went off all right. And then, when it was all over and I was ‘safe,’ I did a simple little thing and got my hand smashed.

As the heroine in “The Black Secret,” Pearl White has a fight with a ruffian who throws her down a flight of stairs. She has had many of these struggles on stairs, one of them continuing down several flights and resulting in her jaw being dislocated.

“In one picture I had to fight with another boy down several flights of stairs. It was real fighting, too; rolling over and over, striking our heads against the banisters and the wall, struggling all the way. I accidentally knocked the other boy unconscious; but aside from that and the inevitable bruises, neither of us was hurt.

“Then we wound up with what looked like a comparatively simple stunt: he was to be sitting on a low bench in the hall below, and I was to jump over the banister from above and land on him. Then we were to roll off onto the floor and continue our fight. It wasn’t a very big jump, and the bench he was on was only about two feet high.

“I made the jump all right, landed on him, and we rolled off. But as we went over, his hand happened to catch me just right, at the side of my neck, and dislocated my jaw! Again the big stunt had gone through safely, and my injury had come in some unexpected mischance.

“Why, I was standing on the curb one day, waiting for a street car. Millions of people do that and never think of danger. Neither did I. But when I stepped off— only about a six-inch step—I somehow fell and broke my ankle.

“When I first went into pictures, we were making some cowboy scenes up in the Bronx, right near New York. I was a good rider; in fact, it was my riding that got me my chance at moving picture work. Although I was a ‘trap’ performer in the circus, I was crazy to be an equestrienne and was always riding the horses around ‘the lot’ in my spare moments. Later, I traveled with a theatrical company, doing one-night stands in the Southwest. And every time I had a chance, I would get a a horse and go cavorting around the country.

“In that way I learned to ride pretty well. When it came to the wild riding necessary in the pictures, I did all kinds of stunts. I’ve been thrown dozens of times; and while I have been knocked out repeatedly, I never was badly injured.

“One day, in making those Wild-West pictures in the Bronx, I was doing a perfectly simple bit of work, just straight riding. However, the sun was in my eyes and 1 didn’t notice a little sapling ahead. It wasn’t thicker than my wrist, anyway. But my pony dashed by so close to the sapling that it struck my knee and broke my knee cap.

“So why worry about the big things? It’s the little ones that get me. There was the time, for instance, when we were making pictures down in Florida. In one scene, I was to jump off a moving steam yacht. And, by the way, I want to say this: I never do a serious stunt without first studying the possibilities of danger, so as to avoid an accident if I can.

“In this case, for example, the director told me to jump from the rail of the yacht, at the middle of the boat, which was to continue steaming ahead until it moved out of the picture. I was to have a life preserver in my hand and was to keep hold of it as I struck the water.

“Well, I did some thinking on my own hook. And then, when the director had gone off to the tug, where the camera man was, and which was to keep abreast of us so as to get a long shot of the whole performance, I hunted up the captain.

‘”Do you know from what part of the boat I am to jump?’ I asked him.

“Why, from toward the stern,’ he said.

‘”Not at all!’ I explained. ‘I’m to jump from the middle of the boat.’

“‘But you can’t do that!’ he said. ‘If I’m steaming ahead, the suction will carry you under the vessel.’

“‘I know that,’ I told him. ‘But if you stop your engine, I will get away, and your momentum will carry you out of the picture all right. I’ll have somebody give you the signal when to stop.’

“I made another change, too. I realized that if I held onto the life preserver when I struck the water, my arm would get an awful wrench. So I let go of the life preserver just before I hit the water, and then caught hold of it again as I came up.

“But,” she went on with a touch of bitterness,”there was one thing which nobody had told me! Perhaps they did not know—certainly I did not know—what was in the water between the yacht and the tug. . . . Sharks! … I saw several of them around me as I swam to the tug; and I was too frightened then to do anything but swim—and pray. I did both as hard as I could.

“But,” she went on with a touch of bitterness,”there was one thing which nobody had told me! Perhaps they did not know—certainly I did not know—what was in the water between the yacht and the tug. . . . Sharks! … I saw several of them around me as I swam to the tug; and I was too frightened then to do anything but swim—and pray. I did both as hard as I could.

“Again luck was with me. Or maybe it was Providence. I believe in praying. I confess that I don’t do enough of it, except when I am frightened. But I’m scared so often that I keep in pretty good practice.

“Anyway, I escaped that time, when the risk was really a serious one. And then the next day, when I was doing a scene on the beach, where you wouldn’t have thought I could get hurt if I tried, I stepped on a shell, cut my foot, had blood poisoning, and was laid up for three weeks.

“At one time, I thought I wanted to be an aviator; so I had a couple of months of off-and-on instructions; off and on as to lessons, I mean; for I never went ‘off’ the ground. About that time we were making a picture in which the hero was cast away on a desert island. The place was really Staten Island, in New York Harbor; but there are parts of it which are deserted as anything you will find in the South Seas.

‘They wanted a scene where the heroine lands on the island in an airplane, rescues the hero, and flies away with him. They thought I would double for this scene; have somebody else actually fly the machine for the long shot of it in the air. They could take close-ups of me starting it and landing.

“But I insisted on making the whole trip. The machine they had was an old one-passenger Wright biplane, so I had to go alone. I never had been in the air by myself. My only experience hid been running the machine on the ground. But the director didn’t know this, and I didn’t tell him.

“As a matter of fact, I made the flight safely. But as I came down to make the landing, I miscalculated the distance and ‘landed’ in the water! If it had been a hydroplane, I might have been all right. But it wasn’t. And when the machine struck, the engine simply turned over with a jump, and the whole thing sank. Luckily I got out and swam ashore. Now, that really was a dangerous stunt, because I didn’t know how to fly an airplane. Yet I wasn’t hurt.

“I had another very unpleasant experience in the air. They wanted a scene showing the heroine taking a little pleasure ride in a captive balloon, such as you will find at many amusement parks. But in this case the villain was to cut the ropes and set the balloon adrift.

“We staged the scene at Palisades Park, across the Hudson from New York City. There was no one in the basket but the aeronaut and myself. According to our plan, after the ropes were cut the balloon would go off over New Jersey, and we would descend after being in the air about fifteen minutes.

“We staged the scene at Palisades Park, across the Hudson from New York City. There was no one in the basket but the aeronaut and myself. According to our plan, after the ropes were cut the balloon would go off over New Jersey, and we would descend after being in the air about fifteen minutes.

“But about ten minutes after we were cut loose, a sudden storm broke. It was April and this was a good old-fashioned April thunderstorm, with rain, wind, lightning, and all the trimmings. I don’t suppose it lasted over twenty minutes, but they seemed to me like twenty years. We were drenched to the skin and half frozen.

“In order to rise above the storm, we threw out ballast and got up to about five thousand feet. Then, when the storm passed and we wanted to come down, we found that we were over New York City! We did not dare to descend there. The balloon might land on the edge of a twenty-story building and tip us into the street.

“For three hours and a half we were in the air; most of the time over the city, although once we were carried two miles out to sea. But we didn’t dare to come down in the water, of course. Most of this time, I was busy tearing a long roll of tissue paper in pieces and dropping them over the side of the basket. As they fell, they would show in which direction the currents of the air below were moving. There seemed to be different levels, on which the currents moved in different directions. At first, the aeronaut would throw out ballast in order to rise; or would let some of the gas escape, in order to descend.

“In this way we jockeyed around, trying to get into a current which would carry us to a safe landing place. But we couldn’t make it. Finally, all the ballast was gone and, to complicate the situation still more, the bag was leaking gas. We had settled down until we were only about a thousand feet above the roofs of New York and were slowly sinking still nearer to them.

“But my luck held; for finally the wind veered, carried us clear of the city, and we came down safely. But that was the longest three hours and a half I ever put in.

“As a rule, when you are doing picture stunts, there isn’t any long-drawn-out suspense. It generally goes with a rush, and the danger is over before you have time to lose your nerve.

“For instance, I have walked a board across an open court between two twelve-story apartment houses. The board was perhaps fifteen feet long and was laid from one roof to the other. If I had made a misstep, or had lost my balance, I should have fallen those twelve stories to the paved courtyard below.”

“Perhaps you’re not afraid of being in high places,’ I said.

“Afraid is too mild a way to put it!” was the earnest response. “I am almost rigid with terror. If I looked down, I should be lost. I am a Catholic, you know; and I never do one of these stunts that terrify me, without saying a ‘Hail, Mary’ as I start.

“Often I have had to jump across a four-foot chasm between two buildings. Four feet isn’t very wide a jump, when you have a running start. But suppose my foot slips, or my toe catches, just as I take off. It that happened—Well, it never has.” Again she rapped on the table beside her.

“Are you superstitious?” I asked.

“No! I believe it’s unlucky to break a mirror—because then you’ll have to buy a new one. I think it would be unlucky to fall in front of a street car—because you might be run over. But I don’t have any so-called mascots, or things that I think bring me luck. I try to be careful, and then I let it go at that. The reason I rap on wood is simply because other people do, and I have picked it up from them.

“Experiences like those I have had make you feel that you will die when your time comes—not before. Anyway, the thing I dread is not death, but being maimed or disfigured. That’s another reason why I prefer the big risks. If I missed my footing and fell a hundred feet, it would kill me. If I fell twenty feet, I might only be crippled for life, or hopelessly disfigured.

“Yesterday we were doing a scene here in the studio and I had to fall backward through a large picture hanging on the wall. It was a fall of less than six feet. It didn’t look like much of a stunt, but I’d rather have jumped off a seventy-foot cliff into the water than have done that little backward tumble onto the floor. Yesterday we did the scene from the front. To-day we do it again from the back of the painting. And I’m afraid! Honestly I am.”

“You speak of jumping off a seventy-foot cliff,” 1 said. “Have you ever done it?”

“You speak of jumping off a seventy-foot cliff,” 1 said. “Have you ever done it?”

“Oh yes, several times. There’s a cliff that high up at Saranac Lake, and I’ve jumped from it for three different pictures. I’m not good at jumping into the water, either. I can drop all right and strike the water with my toes, which is the proper way. But when I jump, I come down on my heels; and that gives a bad jar to the spine.”

“Of course you are a good swimmer?” I asked.

“I can swim pretty well now. But when I first did stunts where I was thrown into the water, I couldn’t swim a stroke. If there had been any hitch in the program, I should have drowned. But you know,” she laughed, “a company has a very good reason, aside from any considerations of humanity, for wanting to save the actor. Especially if the actor is a star.

“Suppose half the scenes of a picture have been made. They have cost a lot of money. And suppose I am the star who is featured in the play. If I am killed, they can’t substitute somebody else; so they try to protect themselves by having all the scenes which are not dangerous made first. The ones in which the star risks his or her neck are done last. Then, if anything does happen, someone can double for the disabled or deceased star, and the picture can still be shown. The close-ups nave already been made. And in the long shots the double will not be recognized.

“For instance, suppose it is that seventy-foot leap up at Saranac. Three separate views of it are taken. There is a close-up of me, just as I am jumping off, and another close-up as I strike the water. Then there is the long shot. To make this, the camera is far enough away to show the whole height of the cliff, and the actual leap from start to finish. There can be no fake about this. The seventy-foot jump is actually made. But the figure is so far away that you can’t recognize the features.

“The close-ups are probably not made at the real cliff at all. In the one which shows the beginning of the leap, I am jumping from a ledge into a net, or perhaps only about ten feet into the water. For the close-up of me striking the water, I have made only a short jump from a bank or a platform, which does not show in the picture.

“Now suppose all the scenes have been made, except the long shot of the actual seventy-foot leap. And suppose something happens to me when I do make that leap. If I am killed, or injured, they can find an expert diver, dress him in my clothes, put a wig on him that will be like my hair, take the long shot—and the picture is saved. So that’s why the dangerous stunt is kept until the last.”

“What was the worst experience you’ve ever had?” I asked.

She thought for a moment, then gave a little laugh.

When a bunch of moving picture German soldiers thrust their bayonets almost within pricking distance of her throat, Pearl White could only shut her eyes and hope that the men behind those particular guns were good judges of distance.

“I think the hardest thing I ever did was during the drive for the Victory Loan. The New York Fire Department sent out one of its huge ladder trucks, with a crew to operate it, and I went along. They would raise the ladder almost straight into the air—not leaning it against a building —and I climbed it, one rung for each subscription from the crowd below. I think there were seventy-two rungs. I went to the very top; then over the top, and down the other side, one rung at a time.

“The worst thing about it all was the slowness: of it. I used to stand on that ladder, simply praying that somebody would take another bond—and take it quickly! People in the crowd, or in the windows, would call to me. Apparently, I would look down and bow. But I had to shut my eyes when I did it. We went all over the city with that awful ladder.”

“But why did you do it, if you were so frightened?”

“I don’t know—one doesn’t want to be a quitter. Being a coward is one thing. You can’t help that. But acting the coward is very different. I’m not ashamed of feeling fear. But I would be ashamed if I let my fear rule me. I guess that’s it.

“There was another time when I did something which absolutely terrified me, and which wasn’t done for the pictures, or for anything as worth while as patriotism either. It was just a ‘publicity’ stunt. I believe it was in 1915, when one of the picture companies was moving into a new building. The scheme was this; I was to climb down the front of the building to an electric light sign, then down this sign to a painters’ scaffold, and paint one letter of the company’s new sign. Our publicity manager had got a steeplejack to make the attempt first, and the steeplejack had proved that it could be done.

“But the manager began to get cold feet as the day approached. So he arranged for me to wear a harness under my clothing and to have strong wires attached to this harness. The wires would not be visible to the crowd in the street; and they would be fastened to something on the roof and ‘paid out’ as I climbed down. Then, if I lost my footing, or my head, or my nerve, I wouldn’t be killed.

“But when the time came, I found that the manager had let a lot of newspaper men come up where I was to start! Well! It would be a fine story, wouldn’t it, to tell about me! How I was all tied with wires. So I told the manager that I wouldn’t have the wires used. It would simply ‘make a Chinaman’ of me.

“‘Well then,’ he declared, ‘you mustn’t go! We’ll call the whole thing off. We can say that you are sick.’

“I was sick; sick with fear! But if I backed out, I should ‘make a Chinaman’ of myself. So I insisted on going through with it.

“I got to the electric sign safely and began to climb down that. It was one of the meanest things I ever saw—that sign. It shook and swung and behaved as if it were bewitched. But I managed to reach the scaffold all right. While I was climbing down, I looked up occasionally, and I could see the manager, leaning over the top, watching me. His face was dead white.

“I painted the letter as I had been told to do; but before I was half through, the manager began calling me to come back. 1 paid no attention to him. I was safe where I was, and I was in no hurry to take the return trip. I was glad he was suffering. I said to myself, ‘He got me into this. Now he can worry a while.’

“I finished the letter on the sign, and then I deliberately painted my own initials on the wall of the building. I made them good and large, too. It was the Saturday before Easter, I remember. I knew they would have to stay there over Sunday, anyway, and I thought I might as well get what I could for myself out of the experience. I think I must have been down there twenty minutes. Then I climbed back. When they helped me over the ledge at the top—the manager fainted.’

“And you?” I asked.

“Oh, I didn’t faint, if that’s what you mean. I never have fainted. I’ve been knocked unconscious a good many times, but I’ve never fainted.”

“You said you were afraid of animals. Have you ever done stunts with lions and other wild beasts?” I asked.

“Yes, of course. Last year we were making a picture down in Cuba, and they had a famous lion, called Jimmie, for some of the scenes. In one of them, I went into a sort of cave, which was already occupied by Jimmie. I sat down on the sand, according to directions, and was proceeding with the action, when Jimmie suddenly leaped at me. Perhaps I swerved aside. At any rate, he missed me and struck the sharp edge of a rock, cutting his paw. He stopped a minute to lick the cut—and then turned to attack me again. But before he could reach me, the trainers were on him.”

“No more lions for you, after that, I imagine!” I said.

She looked at me with the expression I had noticed so often while we were talking, a curious mixture of nonchalance and intensity.

“Not for half hour or so,” she said; “then we did the scene again. Fortunately, Jimmie behaved better that time. Or maybe he’d lost his taste for me.”

‘If the photographer went on turning the camera handle when Jimmie leaped at you, it must have made a great picture,” I said. “Do they often get these thrilling accidental scenes?”

“They happen once in a while, but I never have known of an accident picture that could be used. You see, they never fit into the story. The time I sank the airplane, for instance, the picture couldn’t be used, because the story required me to land safely and to rescue the hero from his desert island. It is always that way. The accident spoils the story.

“Once I had to make a flying leap from a moving automobile to the running board of another machine which was racing abreast of it. I missed the running board and fell. I had on a leather coat, which caught in the wheel, and 1 was carried for at least one complete revolution before the machine could be stopped. But the picture of the accident couldn’t be used, because in the story I made the leap successfully.”

“Speaking of automobiles, I must tell you of the most wonderful nine days I ever spent. It was one summer during the war. I was sick of New York, fed up with Broadway, disgusted with everything and everybody. We had just finished a picture and I had a six-weeks vacation ahead of me. The very first night of it, I packed a bag, had a roll of blankets put into my car, and started out alone to get away from all the noise and glare and sordidness of the city into the good clean country.

“Speaking of automobiles, I must tell you of the most wonderful nine days I ever spent. It was one summer during the war. I was sick of New York, fed up with Broadway, disgusted with everything and everybody. We had just finished a picture and I had a six-weeks vacation ahead of me. The very first night of it, I packed a bag, had a roll of blankets put into my car, and started out alone to get away from all the noise and glare and sordidness of the city into the good clean country.

“I told you that I was afraid of the dark. I am! But I slept every night under the car, in some lonely field away from the road. One night I was frightened half out of my wits when a cow almost stepped on my arm, which was sticking out from under the machine. I used to drive at night, too; and when the road ran through woods I was in terror every minute of the time. But I kept on going. I followed no set route, but wandered around in all directions.

“The fourth day, I turned into a little by-road up near Schenectady and came to a shabby farmhouse. The yard seemed to me to be alive with dogs, which set up a tremendous barking. The rumpus brought a woman to the door, and I asked her for a glass of water. I hadn’t been near a hotel since I had left New York. It had rained more than once; but I had a rain coat and had kept right on going. I would buy food at village stores and eat it when I came to some quiet bit of road. It was a wild proceeding; but I was happy, out under God’s stars, as I told myself, and all that sort of thing.

“Well, the woman asked me if I wouldn’t get out and stay a while. I had been sick of people—but not of people of her sort. So I got out and we two sat there on her little porch and talked for five hours! She was wonderful. Uneducated, so far as schooling went; but with a philosophy of wisdom of her own. I never have felt so small as I did sitting there and listening to her.

“We talked of everything; of right and wrong, of why people are what they are, of what is really worth while, and of what is only on the surface and doesn’t count in the long run.

“It was a strange experience; and, for me, a very wonderful one. I had been half inclined to come back to New York. But after my talk with her, I stayed out five days longer. I think I would have spent the whole six weeks that way if I hadn’t gone to Albany. After nine days of roughing it, I went to a hotel there to have a few hours in a bathtub and to replenish my limited supply of clothing. As luck would have it, I met friends there, and they persuaded me to give up what they considered my mad escapade. But those nine days will always be literally the ‘nine days wonder’ of my life.”

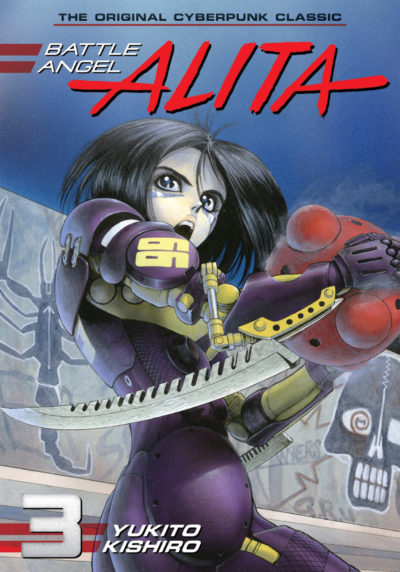

There have been two (or perhaps three) subsequent comic-book incarnations. First was Battle Angel Alita: Last Order, originally published from 2001-14 in Japan. Then came Battle Angel Alita: Holy Night and Other Stories, though this was a collection of four side-stories – hence the “perhaps three”! Most recently, we had Battle Angel Alita: Mars Chronicle (2015-17). Two of the volumes from the first incarnation were adapted into a pair of 30-minute OVAs (Original Video Animation), released in June 1993. Rumblings of a live-action version have been around almost as long, with James Cameron securing the rights to the comic in 1999, having been introduced to the property by Guillermo Del Toro. By the mid-2000’s, a script had been created, but after developing the project in parallel with Avatar, Cameron decided to devote his efforts to that instead, and Alita went on the back-burner.

There have been two (or perhaps three) subsequent comic-book incarnations. First was Battle Angel Alita: Last Order, originally published from 2001-14 in Japan. Then came Battle Angel Alita: Holy Night and Other Stories, though this was a collection of four side-stories – hence the “perhaps three”! Most recently, we had Battle Angel Alita: Mars Chronicle (2015-17). Two of the volumes from the first incarnation were adapted into a pair of 30-minute OVAs (Original Video Animation), released in June 1993. Rumblings of a live-action version have been around almost as long, with James Cameron securing the rights to the comic in 1999, having been introduced to the property by Guillermo Del Toro. By the mid-2000’s, a script had been created, but after developing the project in parallel with Avatar, Cameron decided to devote his efforts to that instead, and Alita went on the back-burner.

I used to read a

I used to read a  wever, there’s still an amazing amount going on in terms of story-line and universe-building. You can easily see how the feature film will only be able to cover perhaps one-quarter of the series. I presume it will begin with the origin story, in which Ido finds the head of Alita in the scrapyard beneath the floating city of Tiphares, and gives it a cybernetic body. He’s a part-time bounty hunter, only to find out quickly, the combat abilities of his new charge far surpass his own. Unfortunately, she has little or no memory of her prior life; where she got these skills and how she ended up in the scrapyard is only revealed well into the series.

wever, there’s still an amazing amount going on in terms of story-line and universe-building. You can easily see how the feature film will only be able to cover perhaps one-quarter of the series. I presume it will begin with the origin story, in which Ido finds the head of Alita in the scrapyard beneath the floating city of Tiphares, and gives it a cybernetic body. He’s a part-time bounty hunter, only to find out quickly, the combat abilities of his new charge far surpass his own. Unfortunately, she has little or no memory of her prior life; where she got these skills and how she ended up in the scrapyard is only revealed well into the series.

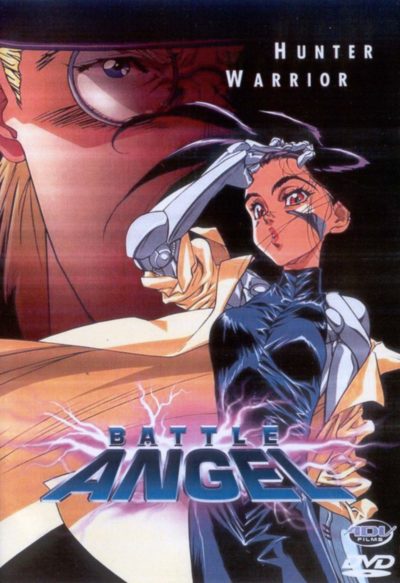

Watching this after having read the manga version, it feels like the anime version can do little more than scratch the surface of the world of Tiphares, in the barely fifty minutes it has to work with across its two OVA (Original Video Animation) volumes. The stories here, originally released in 1993, cover the first two section of the manga, and it looks like much of what we see here will also be included in the live-action film next February. Slightly confusing matters, is the way this uses the original Japanese names. So Tiphares becomes Zalem here, and Hugo is Yugo. Most oddly, the heroine is not called Alita – hence the absence of her name from the title – but Gally. To avoid further confusion, I’m going to be consistent with our other articles on the topic, and stick to the translated ones for what follows.

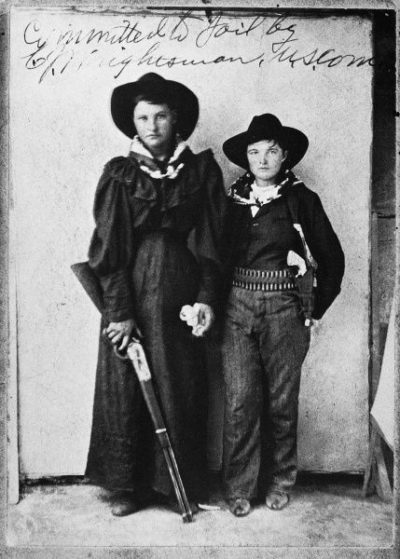

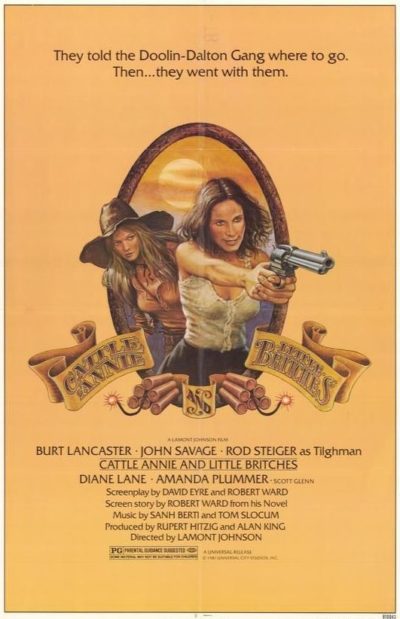

Watching this after having read the manga version, it feels like the anime version can do little more than scratch the surface of the world of Tiphares, in the barely fifty minutes it has to work with across its two OVA (Original Video Animation) volumes. The stories here, originally released in 1993, cover the first two section of the manga, and it looks like much of what we see here will also be included in the live-action film next February. Slightly confusing matters, is the way this uses the original Japanese names. So Tiphares becomes Zalem here, and Hugo is Yugo. Most oddly, the heroine is not called Alita – hence the absence of her name from the title – but Gally. To avoid further confusion, I’m going to be consistent with our other articles on the topic, and stick to the translated ones for what follows. There’s something satisfyingly circular about the story of Cattle Annie and Little Britches. Two teenage girls, inspired by the questionably accurate literary exploits of Western outlaw derring-do, leave their homes and families to join those outlaws. They end up becoming the stuff of these same legends themselves, with their story being turned into a Hollywood movie (see below). Art imitating life imitating art. Given this, discovering the truth behind the myth is almost impossible, with sources telling different versions, and often contradicting each other. As such, take what follows as a best guess…

There’s something satisfyingly circular about the story of Cattle Annie and Little Britches. Two teenage girls, inspired by the questionably accurate literary exploits of Western outlaw derring-do, leave their homes and families to join those outlaws. They end up becoming the stuff of these same legends themselves, with their story being turned into a Hollywood movie (see below). Art imitating life imitating art. Given this, discovering the truth behind the myth is almost impossible, with sources telling different versions, and often contradicting each other. As such, take what follows as a best guess…

For example, rather than being born and brought up in Oklahoma, the duo are portrayed as making their way out to California to seek their fortune, when they’re forcibly detoured to Guthrie, OK, There, they encounter Bill Doolin (Lancaster) when he and his gang visit the town. Annie falls for gang member Bittercreek Newcomb (John Savage) and they end up being taken by him to the gang’s hideout. Their knowledge of the Doolin Gang is entirely based on the embellished stories they’ve heard about them, and they’re disappointing to find reality comes up short.

For example, rather than being born and brought up in Oklahoma, the duo are portrayed as making their way out to California to seek their fortune, when they’re forcibly detoured to Guthrie, OK, There, they encounter Bill Doolin (Lancaster) when he and his gang visit the town. Annie falls for gang member Bittercreek Newcomb (John Savage) and they end up being taken by him to the gang’s hideout. Their knowledge of the Doolin Gang is entirely based on the embellished stories they’ve heard about them, and they’re disappointing to find reality comes up short.

It’s still not w

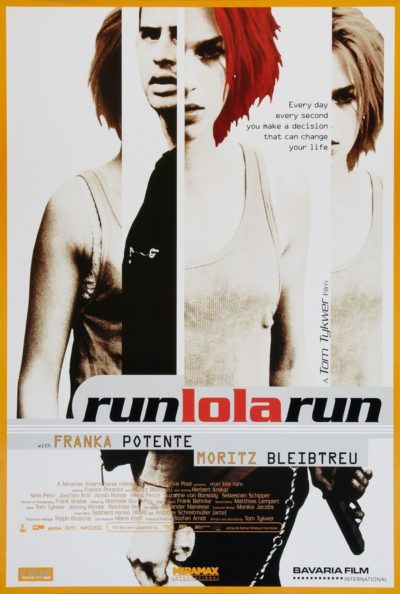

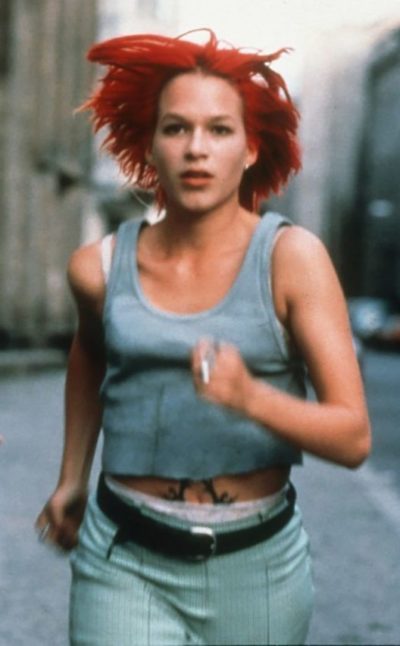

It’s still not w Yet in that light, it’s worth noting she’s not immune to external forces. Indeed, the first domino is her descent of the staircase in her apartment block and an encounter with another resident and his dog. The resulting outcome begins the process of changing the timeline. These are also not complete “resets”. In the opening run, Manni has to show her how to operate the safety on a gun; in the second, she knows what to do. Nor is her power without limits, or Lola could simply go back and prevent her boyfriend from losing the money to begin with. There are, apparently, rules to this game, though who sets them and why, is not a topic addressed in the film.

Yet in that light, it’s worth noting she’s not immune to external forces. Indeed, the first domino is her descent of the staircase in her apartment block and an encounter with another resident and his dog. The resulting outcome begins the process of changing the timeline. These are also not complete “resets”. In the opening run, Manni has to show her how to operate the safety on a gun; in the second, she knows what to do. Nor is her power without limits, or Lola could simply go back and prevent her boyfriend from losing the money to begin with. There are, apparently, rules to this game, though who sets them and why, is not a topic addressed in the film.

Despite what some people

Despite what some people

“I was afraid of people, afraid of animals, afraid of the dark – afraid of everything! We were the poorest children in town, and that’s saying a good deal. Half of the time I didn’t have any shoes. And because we were poor and because we were cowards, all the other kids picked on us.

“I was afraid of people, afraid of animals, afraid of the dark – afraid of everything! We were the poorest children in town, and that’s saying a good deal. Half of the time I didn’t have any shoes. And because we were poor and because we were cowards, all the other kids picked on us. “Everything went smoothly until he tried to carry me up the stairs. I was still bound, and he had thrown me over his shoulder, with my head hanging down his back. He had carried me up six or seven steps when he lost his balance, and toppled over backward. I couldn’t help myself, so I struck on the top of my head, displacing several vertebra.

“Everything went smoothly until he tried to carry me up the stairs. I was still bound, and he had thrown me over his shoulder, with my head hanging down his back. He had carried me up six or seven steps when he lost his balance, and toppled over backward. I couldn’t help myself, so I struck on the top of my head, displacing several vertebra.

“But,” she went on with a touch of bitterness,”there was one thing which nobody had told me! Perhaps they did not know—certainly I did not know—what was in the water between the yacht and the tug. . . . Sharks! … I saw several of them around me as I swam to the tug; and I was too frightened then to do anything but swim—and pray. I did both as hard as I could.

“But,” she went on with a touch of bitterness,”there was one thing which nobody had told me! Perhaps they did not know—certainly I did not know—what was in the water between the yacht and the tug. . . . Sharks! … I saw several of them around me as I swam to the tug; and I was too frightened then to do anything but swim—and pray. I did both as hard as I could. “We staged the scene at Palisades Park, across the Hudson from New York City. There was no one in the basket but the aeronaut and myself. According to our plan, after the ropes were cut the balloon would go off over New Jersey, and we would descend after being in the air about fifteen minutes.

“We staged the scene at Palisades Park, across the Hudson from New York City. There was no one in the basket but the aeronaut and myself. According to our plan, after the ropes were cut the balloon would go off over New Jersey, and we would descend after being in the air about fifteen minutes. “You speak of jumping off a seventy-foot cliff,” 1 said. “Have you ever done it?”

“You speak of jumping off a seventy-foot cliff,” 1 said. “Have you ever done it?”

“Speaking of automobiles, I must tell you of the most wonderful nine days I ever spent. It was one summer during the war. I was sick of New York, fed up with Broadway, disgusted with everything and everybody. We had just finished a picture and I had a six-weeks vacation ahead of me. The very first night of it, I packed a bag, had a roll of blankets put into my car, and started out alone to get away from all the noise and glare and sordidness of the city into the good clean country.

“Speaking of automobiles, I must tell you of the most wonderful nine days I ever spent. It was one summer during the war. I was sick of New York, fed up with Broadway, disgusted with everything and everybody. We had just finished a picture and I had a six-weeks vacation ahead of me. The very first night of it, I packed a bag, had a roll of blankets put into my car, and started out alone to get away from all the noise and glare and sordidness of the city into the good clean country. Before we get into looking forward to next year, let’s look back at 2017, and what happened to the films mentioned

Before we get into looking forward to next year, let’s look back at 2017, and what happened to the films mentioned

Cocaine Godmother (Jan 20)

Cocaine Godmother (Jan 20)

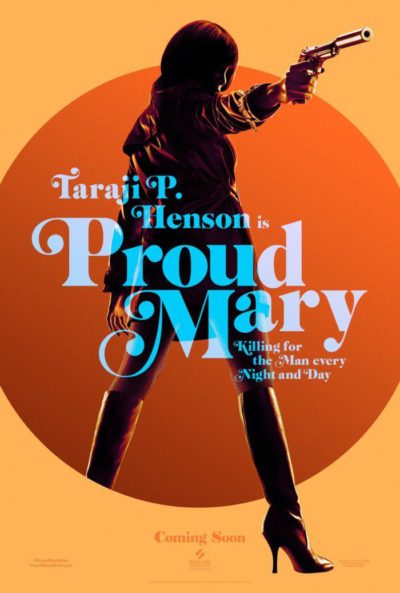

Proud Mary (Jan 12)

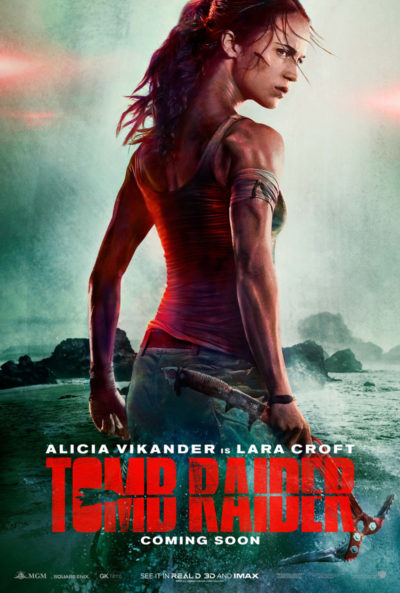

Proud Mary (Jan 12) Tomb Raider (Mar 16)

Tomb Raider (Mar 16)

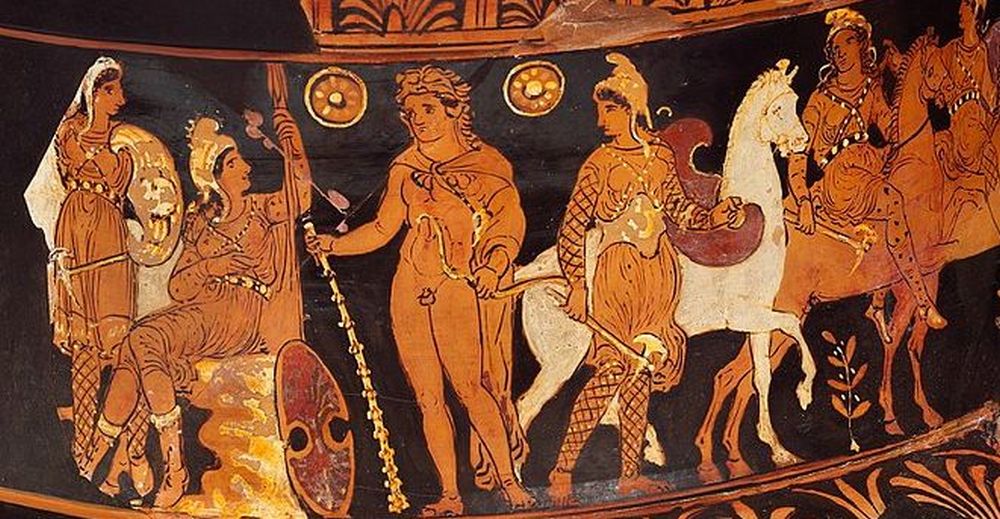

Hippolyte, queen of the Amazons, with Herakles between Amazons. Fragment of a terracotta volute-krater, created: circa 330–310 B.C

Hippolyte, queen of the Amazons, with Herakles between Amazons. Fragment of a terracotta volute-krater, created: circa 330–310 B.C The main source for information is Herodotus, a historian of the fifth century B.C. The story he tells starts with the Greeks defeating the Amazons and taking three shipfuls of them captive, only for the prisoners to overthrow their captors, and land in Scythia, on the north of the Black Sea. “The Amazons had nothing except their arms and their horses, and got their living… by hunting and by taking booty.” There, they fought the locals, until the Scythians decided to make love not war, and sent their young men out to befriend the raiders, which they did so successfully, it led eventually to an entire separate tribe, the Sauromatai, about whom he says:

The main source for information is Herodotus, a historian of the fifth century B.C. The story he tells starts with the Greeks defeating the Amazons and taking three shipfuls of them captive, only for the prisoners to overthrow their captors, and land in Scythia, on the north of the Black Sea. “The Amazons had nothing except their arms and their horses, and got their living… by hunting and by taking booty.” There, they fought the locals, until the Scythians decided to make love not war, and sent their young men out to befriend the raiders, which they did so successfully, it led eventually to an entire separate tribe, the Sauromatai, about whom he says: They were, however, still generally regarded as being little more than mythical. Belief in them as a historical entity was limited to the fringe, most notably Swiss scholar Johann Jakob Bachofen. In 1861 Bachofen published Mother Right: an investigation of the religious and juridical character of matriarchy in the Ancient World. This suggested civilization had gone through four phases, including “Das Mutterecht,” a matriarchal ‘lunar’ phase, which was the origin of the Amazon myth. Some suggest he was an influence on Richard Wagner, in particular with regard to the Valkyries.

They were, however, still generally regarded as being little more than mythical. Belief in them as a historical entity was limited to the fringe, most notably Swiss scholar Johann Jakob Bachofen. In 1861 Bachofen published Mother Right: an investigation of the religious and juridical character of matriarchy in the Ancient World. This suggested civilization had gone through four phases, including “Das Mutterecht,” a matriarchal ‘lunar’ phase, which was the origin of the Amazon myth. Some suggest he was an influence on Richard Wagner, in particular with regard to the Valkyries. Wonder Woman is just the most recent, and certainly most successful incarnation of the Amazon clan to find its way into the mass media. Virtually since the time of Herodotus, there have been a steady stream of tales, more or less exploiting prurient interest in the concept of a tribe entirely consisting of women. It has been used in ways both derogatory and complimentary: to mock women for losing their femininity, as well as to inspire them in their battle for increased rights. The suffragettes of the early twentieth century, in particular, frequently used the Amazons as a totem in their poems and stories.

Wonder Woman is just the most recent, and certainly most successful incarnation of the Amazon clan to find its way into the mass media. Virtually since the time of Herodotus, there have been a steady stream of tales, more or less exploiting prurient interest in the concept of a tribe entirely consisting of women. It has been used in ways both derogatory and complimentary: to mock women for losing their femininity, as well as to inspire them in their battle for increased rights. The suffragettes of the early twentieth century, in particular, frequently used the Amazons as a totem in their poems and stories. There have been no shortage of subsequent films to take the Amazon theme – though most of these bear about as much resemblance to the myth, as the myth does to the Scythians who inspired it! I’m not even going to attempt a comprehensive listing of these. Instead, I’ll pick and choose ten somewhat representative candidates, some of which have been reviewed on this site. They’re listed in chronological order.

There have been no shortage of subsequent films to take the Amazon theme – though most of these bear about as much resemblance to the myth, as the myth does to the Scythians who inspired it! I’m not even going to attempt a comprehensive listing of these. Instead, I’ll pick and choose ten somewhat representative candidates, some of which have been reviewed on this site. They’re listed in chronological order. The other television show people will generally associate with Amazons is, of course, Xena: Warrior Princess. This is a bit of a grey area: despite sharing a number of characteristics, Xena herself was never a formal member of the Amazon tribe, despite helping them out on a number of occasions. However, irritating sidekick Gabrielle became their queen (more by chance than intent), and over the six seasons for which the show ran, there were typically between two and four episodes per series, featuring the tribe to some extent.

The other television show people will generally associate with Amazons is, of course, Xena: Warrior Princess. This is a bit of a grey area: despite sharing a number of characteristics, Xena herself was never a formal member of the Amazon tribe, despite helping them out on a number of occasions. However, irritating sidekick Gabrielle became their queen (more by chance than intent), and over the six seasons for which the show ran, there were typically between two and four episodes per series, featuring the tribe to some extent.