Literary rating: ★★★

Kick-butt quotient: ☆☆☆☆

“Have you not learned by this time that I am not a weak woman, but a strong one? You have harried me and injured me and wronged me and set tortures for me, but here I stand, unharmed. This day I will have my revenge.”

“Have you not learned by this time that I am not a weak woman, but a strong one? You have harried me and injured me and wronged me and set tortures for me, but here I stand, unharmed. This day I will have my revenge.”

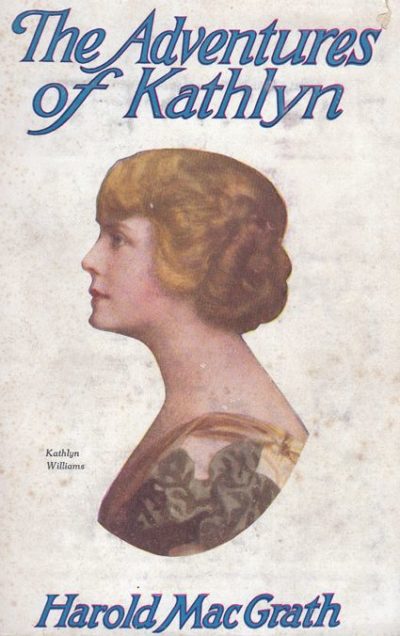

As we discussed earlier this week, the novel is an adaptation of the 13-part serial by the same name starring Kathlyn Williams. The first episode was originally released between Christmas and New Year 1913, and the book was published a few days later, as a tie-in. With both the serial and the feature-length version of the story, released in 1916, both almost entirely lost (one episode and print fragments remaining), the book is virtually all we have to go on in terms of documenting the proto-action heroine who is its titular character.

Kathlyn Hare is the daughter of Colonel Hare, a noted “bring ’em back alive” hunter, who provides animals to circuses and zoos. He had spent many years searching for big game on the Indian sub-continent, in particular the country of Allaha, where he saved the king from a leopard attack. Years later, the senile king makes the Colonel his successor, much to the chagrin of Prince Umballah. The Colonel returns to Allaha, intending to abdicate, leaving a sealed letter behind, for Kathlyn and her sister Winnie to open if he doesn’t come back.

When that comes to pass, the letter triggers Kathlyn’s departure across the world to Allaha, on a courageous mission to rescue her father. Before it’s over, and Umballah is finally defeated, there will be encounters with wild creatures, wilder locals, and an almost endless stream of perils, both natural and man-made. Fortunately, there’s the brave explorer Bruce to help out, as well as some friendly natives, and not least, Kathlyn’s very particular set of skills, involving a particular affinity for animals.

With its action-wilderness setting and breathless pace, Kathlyn feels almost like the ancestor of Lara Croft, though she defers significantly to the men when it comes to the heavy lifting and most of the fighting. But there’s a lengthy period where she has to fend entirely for herself in the jungle. Considering this comes from a time before women were even allowed to vote, she still makes for a striking character. Of course, this dates from a different era, and the unfortunate attitudes of the time, more than a century ago, are frequently reflected in the content. When Kathlyn is informed she is to marry Umballah, there are a million valid reasons to be horrified: he has basically abducted her, after all. But the one the author chooses to have Kathlyn express? “Marry you? Oh, no! Mate with you, a black?”

But, wait! There’s more:

- Sexism! “Not a sign of that natural hysteria of woman, though [Kathlyn] had been through enough to drive insane a dozen ordinary women.”

- Racism! “The Hindus are a suicidal race.”

- Sexism and racism! “The women of [Umballa’s] race were chattels, lazy and inert, without fire, merely drudges or playthings.”

Painful though such sentiments obviously are, I feel you can’t validly judge a vintage book by modern standards, any more than you can complain that Shakespeare’s play do not depict parliamentary democracies. If you feel such things are important, however, this novel is likely not for you.

The writing style, while enthusiastic, is occasionally odd in that it chooses to skip over what should be thrilling moments. I wonder if perhaps this was the book’s way of not stealing the serial’s thunder? For example, as Kaitlyn sets off, accompanying a big cat her father was shipping to its end buyer, a major incident is all but entirely skipped over thus: “How the lion escaped, how the fearless young woman captured it alone, unaided, may be found in the files of all metropolitan newspapers.” Uh, what? But there are times when MacGrath does hit it out of the park, descriptively: “In the blue of night the temple looked as though it had been sculptured out of mist. Here and there the heavy dews, touched by the moon lances, flung back flames of sapphire, cold and sharp.”

The writing style, while enthusiastic, is occasionally odd in that it chooses to skip over what should be thrilling moments. I wonder if perhaps this was the book’s way of not stealing the serial’s thunder? For example, as Kaitlyn sets off, accompanying a big cat her father was shipping to its end buyer, a major incident is all but entirely skipped over thus: “How the lion escaped, how the fearless young woman captured it alone, unaided, may be found in the files of all metropolitan newspapers.” Uh, what? But there are times when MacGrath does hit it out of the park, descriptively: “In the blue of night the temple looked as though it had been sculptured out of mist. Here and there the heavy dews, touched by the moon lances, flung back flames of sapphire, cold and sharp.”

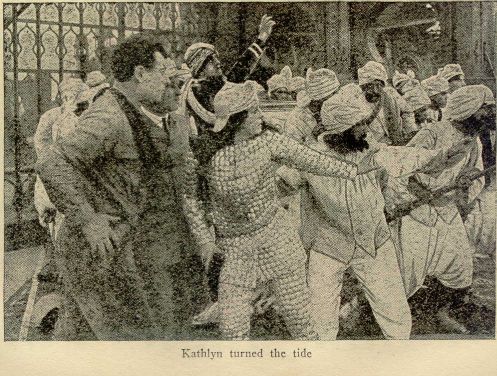

Or there’s this stirring description of Kathlyn, in her role as a “Joan of Allaha”: “With the sun breaking in lances of light against the ancient chain armor, her golden hair flying behind her like a cloud, on, on, Kathlyn ran, never stumbling, never faltering, till she came out into the square before the palace. Like an Amazon of old, she called to the scattering revolutionists, called, harangued, smothered them under her scorn and contempt, and finally roused them to frenzy.” It’s sections like this which make me feel it’s a real shame we’ll never be able to experience the theatrical version of this story. On the other hand, the book does have the advantage of being able to include dialogue, something not available in the silent era, so it might still be more accessible to the modern audience.

I found it an interesting snapshot of a bygone era, and if you’re happy to take this for what it is, and forgive the crude stereotyping, it’s an entertaining and fast-paced read (if occasionally repetitive, in terms of story – how many times is Kathlyn and her family going to escape the clutches of Umballah and not GTFO?). Time for a remake starring Saoirse Ronan, I’d say!

Author: Harold MacGrath

Publisher: Originally in 1914 by the Bobbs-Merrill company, it is now available free from Project Gutenberg, in a variety of formats.