“A cleaved head never plots.”

“A cleaved head never plots.”

“I swear to you, this death will be avenged. And not in the afterlife.” –Freydis Eiriksdotter

Most readers with any knowledge of early American history are aware that Viking sailors, faring south-westward from Greenland, discovered mainland North America around the year 1000 A.D. No lasting settlements were made, but archaeologists have excavated the temporary settlement at L’Anse aux Meadows in present-day Newfoundland (probably the one referred to in the sagas as Straumsfjord). Our main contemporary historical sources for the Viking voyages to “Vinland” are two oral Icelandic sagas, committed to writing about 250 years after the events, which differ in details but basically present a common core of factual information. (The skalds who composed and transmitted the sagas weren’t composing fiction; they were recording history for an aliterate society, although they sometimes garbled or misunderstood details.)

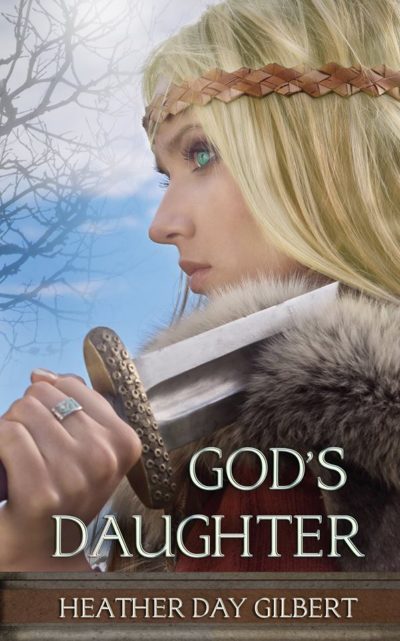

Evangelical Christian author Heather Day Gilbert has taken these sagas, coupled with serious research into the Viking history and culture of that era, plausibly reconstructed a unified picture of the events they present, and brought it to life in a masterful historical series, The Vikings of the New World Saga, consisting of two novels, God’s Daughter and this sequel. Faithful to known facts, she uses her imagination to flesh them out, and to reconstruct believable personalities for the major and minor players in the events. (I’ve read modern re-tellings of the sagas, though not the sagas themselves, and could recognize persons and events in both books.) The first book focused on Gudrid, former pagan priestess (now a Christian) and healer; I wouldn’t really characterize her as an action heroine, though she does pack a blade and is psychologically prepared to fight if she has to. However, this one focuses on her half-sister-in-law by a previous marriage, Freydis, out-of-wedlock daughter of Eirik the Red, and she’s most definitely a butt-kicking lady.

Historical fiction about real-life people uses imagination to reconstruct the details history leaves out, and especially the inner personalities and motivations that history may record imperfectly or not at all. The Icelandic sagas don’t remember Freydis kindly: she’s depicted as a vicious, treacherous psychopath who becomes the New World’s first mass murderer. BUT…. 1.) No historians, medieval or modern, are wholly free from biases that shape their reaction to their material. Gender relations in early Scandinavian/Germanic and Celtic society, as reflected in these books, were comparatively more egalitarian and meritocratic than those of the “civilized” states of southern Europe. By the 13th century, though, when the oral sagas were being committed to writing, the more patriarchal and stratified attitudes of the latter were re-shaping thought and practice in the northern lands. To these historiographers, a woman who clearly didn’t fit their picture of proper gender roles may well have been seen as an obviously deviant villainess by definition, whose actions called for censorious treatment. 2.) Even some of the details recorded by the saga compilers themselves, if one reads between the lines, cast doubt on the supposedly innocent and pacific intentions of Freydis’ adversaries. And 3.), the two key conversations in the sagas that cast Freydis in the worst light, taken at face value, were totally private conversations that none of the original tellers of the material could actually have been privy to. They’re imaginative reconstructions, just as much as Gilbert’s dialogue is –and they’re reconstructions created by writers with an ideological agenda of their own.

Gilbert follows the factual account of events in the sagas faithfully (even including the two conversations I find suspect). But she fleshes out the picture with a more sympathetic vision, and a broader reconstruction of a plausible context, that gives us a very different picture of what (may have) actually happened on the Vineland coast a thousand years ago. The Freydis who emerges here isn’t an evil harridan, and isn’t psychotic. What she is is a tough-as-nails young woman who’s the product of a society that puts a premium on physical courage and fighting ability, who’s had to fight tooth and nail for anything she’s ever gotten, who didn’t feel loved as a child, never knew her birth mother, and doesn’t show love or give trust very easily, a female warrior (in her culture, that wasn’t a contradiction in terms) who killed men in combat while she was still in her teens, who doesn’t readily take orders from any man, woman, or deity, and who isn’t a total stranger to the effects of the special kind of dried mushrooms imbibed by Viking “berserkers” –which are as potent as modern-day “angel dust,” and just as dangerous. She’s also a smart, competent woman (it says something that she’s the expedition leader here, not her husband) with principles as strong as steel, and deep reserves of love and loyalty. And like all of us, she’s a woman on a spiritual journey … which might not end where it began. In real life, the Vikings of succeeding generations never forgot her. Modern readers probably won’t, either.

Gilbert follows the factual account of events in the sagas faithfully (even including the two conversations I find suspect). But she fleshes out the picture with a more sympathetic vision, and a broader reconstruction of a plausible context, that gives us a very different picture of what (may have) actually happened on the Vineland coast a thousand years ago. The Freydis who emerges here isn’t an evil harridan, and isn’t psychotic. What she is is a tough-as-nails young woman who’s the product of a society that puts a premium on physical courage and fighting ability, who’s had to fight tooth and nail for anything she’s ever gotten, who didn’t feel loved as a child, never knew her birth mother, and doesn’t show love or give trust very easily, a female warrior (in her culture, that wasn’t a contradiction in terms) who killed men in combat while she was still in her teens, who doesn’t readily take orders from any man, woman, or deity, and who isn’t a total stranger to the effects of the special kind of dried mushrooms imbibed by Viking “berserkers” –which are as potent as modern-day “angel dust,” and just as dangerous. She’s also a smart, competent woman (it says something that she’s the expedition leader here, not her husband) with principles as strong as steel, and deep reserves of love and loyalty. And like all of us, she’s a woman on a spiritual journey … which might not end where it began. In real life, the Vikings of succeeding generations never forgot her. Modern readers probably won’t, either.

Gilbert brings Freydis’ world vividly to life here, without employing info-dumps or cluttering the narrative with excessive details. (She includes a family tree for Freydis and a short list of other characters in the back, along with a short glossary of Viking terms used in the text; but I personally didn’t need the former, and with my Scandinavian background, the latter only included a couple of words I didn’t know –and I’d roughly deduced the meanings of those from the context already. Even readers who haven’t read much about Vikings, I think, could guess the definitions of all these terms the same way.) This is a very taut, gripping read, with a lot of suspense in the first part even when you know the general outline of the history, and the plot continues to hold dangers and surprises up to the denouement and beyond. It’s written in first-person, present-tense, which puts us inside Freydis’ head and bonds us to her quickly. As in the first book, the characterizations are believable and vivid. All told, this is historical fiction at its finest! I give it my highest recommendation, and I’m looking forward to reading more of Gilbert’s work.

I would strongly advise reading both books in order; they have many of the same characters, and it will help you as a reader to come to this book with the better and deeper understanding of the relationships, personalities and general situation that reading the first book will give you. Action heroine fans usually like other kinds of strong heroines as well, and Gudrid easily fits into that sorority.

Full disclosure: I was gifted with a free copy of this work by the author, just because she knew I wanted to read it. I wasn’t asked to give a favorable review (or, really, any review at all) –that had to be earned, and it was earned in abundance.

Author: Heather Day Gilbert

Publisher: WoodHaven Press, available through Amazon, both for Kindle and as a printed book.

A version of this review previously appeared on Goodreads.

I must admit, my initial reaction to this was, it is less than a film, than footage from a group of Viking LARPers (Live-action Role-playing). The resources on view here are… not great. But the deeper I went into this, the more I found myself able to forgive the limited budget, and began to appreciate the story it was telling, and the characters inhabiting it. Oh, there are still major problems, such as in the “battle scenes”. And I use quotes there, since the count of participants there feels like it might reach… eight, if we’re being charitable. But when it wasn’t making ill-advised efforts to be epic in scale, I ended up enjoying this, and subsequently bought the Blu-ray.

I must admit, my initial reaction to this was, it is less than a film, than footage from a group of Viking LARPers (Live-action Role-playing). The resources on view here are… not great. But the deeper I went into this, the more I found myself able to forgive the limited budget, and began to appreciate the story it was telling, and the characters inhabiting it. Oh, there are still major problems, such as in the “battle scenes”. And I use quotes there, since the count of participants there feels like it might reach… eight, if we’re being charitable. But when it wasn’t making ill-advised efforts to be epic in scale, I ended up enjoying this, and subsequently bought the Blu-ray.

There is certainly room for reworking of the tale of Beowulf and Grendel, and making the heroines of this version female is what got me interested in it. However, the warning signs were out very quickly. Opening titles which said “Denmark… 500 AD… (-ish)” are a good sign of what to expect, for it’s clear that the makers were not happy to leave their changes at that. Indeed, they consciously embrace anachronism, especially in the dialogue, which is thoroughly modern, and could not be further from the epic poetry of the original if they tried. And I suspect they

There is certainly room for reworking of the tale of Beowulf and Grendel, and making the heroines of this version female is what got me interested in it. However, the warning signs were out very quickly. Opening titles which said “Denmark… 500 AD… (-ish)” are a good sign of what to expect, for it’s clear that the makers were not happy to leave their changes at that. Indeed, they consciously embrace anachronism, especially in the dialogue, which is thoroughly modern, and could not be further from the epic poetry of the original if they tried. And I suspect they  ★★★

★★★

“A cleaved head never plots.”

“A cleaved head never plots.” Gilbert follows the factual account of events in the sagas faithfully (even including the two conversations I find suspect). But she fleshes out the picture with a more sympathetic vision, and a broader reconstruction of a plausible context, that gives us a very different picture of what (may have) actually happened on the Vineland coast a thousand years ago. The Freydis who emerges here isn’t an evil harridan, and isn’t psychotic. What she is is a tough-as-nails young woman who’s the product of a society that puts a premium on physical courage and fighting ability, who’s had to fight tooth and nail for anything she’s ever gotten, who didn’t feel loved as a child, never knew her birth mother, and doesn’t show love or give trust very easily, a female warrior (in her culture, that wasn’t a contradiction in terms) who killed men in combat while she was still in her teens, who doesn’t readily take orders from any man, woman, or deity, and who isn’t a total stranger to the effects of the special kind of dried mushrooms imbibed by Viking “berserkers” –which are as potent as modern-day “angel dust,” and just as dangerous. She’s also a smart, competent woman (it says something that she’s the expedition leader here, not her husband) with principles as strong as steel, and deep reserves of love and loyalty. And like all of us, she’s a woman on a spiritual journey … which might not end where it began. In real life, the Vikings of succeeding generations never forgot her. Modern readers probably won’t, either.

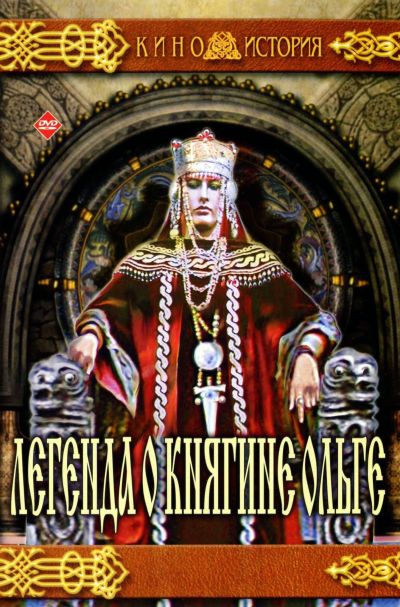

Gilbert follows the factual account of events in the sagas faithfully (even including the two conversations I find suspect). But she fleshes out the picture with a more sympathetic vision, and a broader reconstruction of a plausible context, that gives us a very different picture of what (may have) actually happened on the Vineland coast a thousand years ago. The Freydis who emerges here isn’t an evil harridan, and isn’t psychotic. What she is is a tough-as-nails young woman who’s the product of a society that puts a premium on physical courage and fighting ability, who’s had to fight tooth and nail for anything she’s ever gotten, who didn’t feel loved as a child, never knew her birth mother, and doesn’t show love or give trust very easily, a female warrior (in her culture, that wasn’t a contradiction in terms) who killed men in combat while she was still in her teens, who doesn’t readily take orders from any man, woman, or deity, and who isn’t a total stranger to the effects of the special kind of dried mushrooms imbibed by Viking “berserkers” –which are as potent as modern-day “angel dust,” and just as dangerous. She’s also a smart, competent woman (it says something that she’s the expedition leader here, not her husband) with principles as strong as steel, and deep reserves of love and loyalty. And like all of us, she’s a woman on a spiritual journey … which might not end where it began. In real life, the Vikings of succeeding generations never forgot her. Modern readers probably won’t, either. While the film itself is not that good, it did introduce me to a new action heroine of history: Olga of Kiev, who seems to have been a serious bad-ass, even by the high standards of European bad-asses of the time. There’s some suggestion she was of Viking extraction, with her name originally Helga, and that would certainly make sense. She married Igor of Kiev around 903, and after his death, ruled the state of Kievan Rus’ for 18 years, in the name of her young son, Svyatoslav. The Russian Primary Chronicle

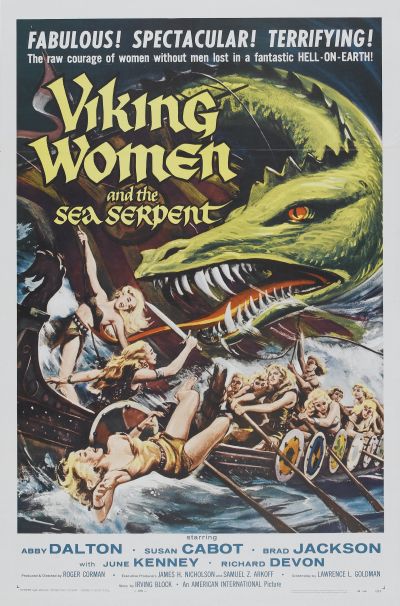

While the film itself is not that good, it did introduce me to a new action heroine of history: Olga of Kiev, who seems to have been a serious bad-ass, even by the high standards of European bad-asses of the time. There’s some suggestion she was of Viking extraction, with her name originally Helga, and that would certainly make sense. She married Igor of Kiev around 903, and after his death, ruled the state of Kievan Rus’ for 18 years, in the name of her young son, Svyatoslav. The Russian Primary Chronicle  I can see why, purely for reason of brevity, the title above was preferred to the full one of The Saga of the Viking Women and Their Voyage to the Waters of the Great Sea Serpent, even though the latter is more accurate. For the Sea Serpent has a supporting role here, met once on their way in, and again on the way out – it’s much more about what happens in the middle. Three years after their men left, the women of the Stannjold clan leave their shores under the command of Desir (Dalton), trying to find out what happened to them. Encounter #1 with the monster leads them to be shipwrecked on the same shores of the Grimault tribe as their menfolk, whose king, Stark (Devon), has set them to work as slaves in his mines. After initially appearing to welcome the women, it becomes clear that Stark has plans for the new arrivals as well. Viking high-priestess Enger (Cabot) has her own agenda, however: having set her eyes both on Desir’s husband and, for more immediate and pragmatic reasons, Stark, she sabotages Desir’s first attempt to free the men.

I can see why, purely for reason of brevity, the title above was preferred to the full one of The Saga of the Viking Women and Their Voyage to the Waters of the Great Sea Serpent, even though the latter is more accurate. For the Sea Serpent has a supporting role here, met once on their way in, and again on the way out – it’s much more about what happens in the middle. Three years after their men left, the women of the Stannjold clan leave their shores under the command of Desir (Dalton), trying to find out what happened to them. Encounter #1 with the monster leads them to be shipwrecked on the same shores of the Grimault tribe as their menfolk, whose king, Stark (Devon), has set them to work as slaves in his mines. After initially appearing to welcome the women, it becomes clear that Stark has plans for the new arrivals as well. Viking high-priestess Enger (Cabot) has her own agenda, however: having set her eyes both on Desir’s husband and, for more immediate and pragmatic reasons, Stark, she sabotages Desir’s first attempt to free the men.

14th-century Norway, not long after the Black Death has decimated the population. Signe (Andreasen) and her family are on the road, seeking a new life, when they are attacked by bandits. Signe is captured and taken to their camp, ruled by Dagmar (Berdal); she was expelled from the nearby town, whose inhabitants thought she was a witch. Signe isn’t the first girl abducted to give the matriarch a family; there’s also Frigg (Olin), a younger girl whom Dagmar is inducting into the ways of the clan. But Frigg is not there yet, and help Signe to escape: needless to say, an enraged Dagmar and the rest of her gang, are soon hot in pursuit, chasing them across the chilly (and beautifully-photographed) wilderness.

14th-century Norway, not long after the Black Death has decimated the population. Signe (Andreasen) and her family are on the road, seeking a new life, when they are attacked by bandits. Signe is captured and taken to their camp, ruled by Dagmar (Berdal); she was expelled from the nearby town, whose inhabitants thought she was a witch. Signe isn’t the first girl abducted to give the matriarch a family; there’s also Frigg (Olin), a younger girl whom Dagmar is inducting into the ways of the clan. But Frigg is not there yet, and help Signe to escape: needless to say, an enraged Dagmar and the rest of her gang, are soon hot in pursuit, chasing them across the chilly (and beautifully-photographed) wilderness.

Hammer were best known for their horror movies, but tried virtually every genre save Westerns at one time or another. This Roman “epic” is loosely based on the life of Boadicea, who led a revolt against the Romans in the first century A.D. They get the name of her tribe right (the Iceni), and some basic facts, such as her suicide after capture, but change her name to Salina and sprinkle in some wild inaccuracies. Despite the title, there are no actual Vikings to be found, and we also get the Druids worshipping Zeus, a Greek god!

Hammer were best known for their horror movies, but tried virtually every genre save Westerns at one time or another. This Roman “epic” is loosely based on the life of Boadicea, who led a revolt against the Romans in the first century A.D. They get the name of her tribe right (the Iceni), and some basic facts, such as her suicide after capture, but change her name to Salina and sprinkle in some wild inaccuracies. Despite the title, there are no actual Vikings to be found, and we also get the Druids worshipping Zeus, a Greek god!