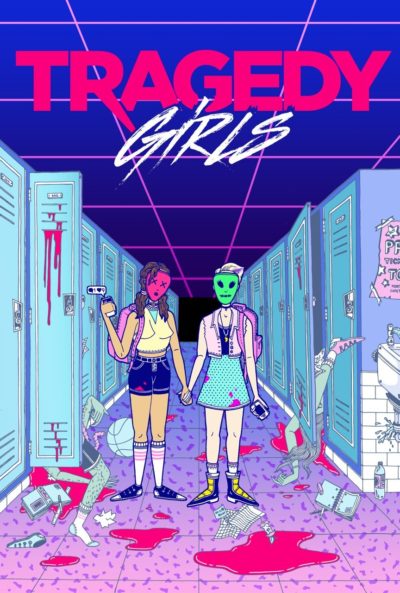

★★★

“Like, rather than retweet.”

Playing like a more social media-conscious version of Heathers, the central characters are high school girls McKayla (Shipp) and Sadie (Hildebrand). They believe their town of Rosedale is the hunting territory of a serial killer, whom the police won’t acknowledge, and the girls have a (not very successful) blog, Tragedy Girls, about the case. The pair succeed in luring out and capturing the killer (Durand), and discover that if they continue operating in his name, they and their site experiences a rise in popularity.

Playing like a more social media-conscious version of Heathers, the central characters are high school girls McKayla (Shipp) and Sadie (Hildebrand). They believe their town of Rosedale is the hunting territory of a serial killer, whom the police won’t acknowledge, and the girls have a (not very successful) blog, Tragedy Girls, about the case. The pair succeed in luring out and capturing the killer (Durand), and discover that if they continue operating in his name, they and their site experiences a rise in popularity.

Except, murderin’ ain’t easy, especially when their initial crimes are dismissed by authorities to avoid causing a panic. McKayla and Sadie clearly need to step up their game. Except as things escalate, there’s a growing sense of dissension in the ranks, both with regard to the directions each feels they should take with their efforts, and over Jordan (Quaid), a cute classmate who help edit videos for the site… Will it be “Sisters before misters”? Or are those creative differences going to lead to the band splitting up, just as they achieve their desired fame?

The target here is obvious, yet certainly worthy of repeated stabbing with a sharp object. I have a deep disdain for the vapid lives of Internet “celebrities”, who measure themselves purely in the number of likes, follows and shares social media, and will do whatever it takes to get them. The reductio ad absurdum in this case is that even cold-blooded murder is not beyond the pale, if it gets these attention-seekers what they crave. It’s a depressingly accurate view of unformed teenage morality, that the end justifies the means.

Credit MacIntyre for clearly knowing his horror stuff, from an opening scene which is as much a parody of slasher films as an introduction. Chris initially mistook it for the real thing, turning to ask me with dripping sarcasm, “And what is the title of this gem?” [A subsequent, blink-and-you’ll-miss-it reference to the amazing Martyrs, was the point in my initial viewing where I stopped, realizing this merited watching with her]. He also has the guts to take the premise to its logical, and very dark, conclusion – here, it does surpass Heathers, which in one early version ended in the entire school blowing up. Given current cultural squeamishness led to a TV series based on Heathers being canned entirely in the US, this is no small feat.

Yet in other ways, it’s still well short of its inspiration. Neither of the leads have the likeability Winona Ryder brought to Veronica Sawyer, everyone else is here depicted as little more than occasionally useful idiots, and the dialogue fails to ‘pop’ in the immensely quotable way Daniel Waters’ script achieved. These factors help lead to a middle section in desperate need of both escalation and an antagonist – other than the one who spends most of the film locked up in a basement. If still worth a look, and rarely less than interesting, I doubt anyone will be rebooting this in 25 years.

Dir: Tyler MacIntyre

Star: Alexandra Shipp, Brianna Hildebrand, Kevin Durand, Jack Quaid

It would, certainly, be easy to look at the poverty-row production values here, and dismiss this contemptuously as a bad film. I mean, the very first shot supposedly sets the scene at the infamous New England house in 1892, where Lizzie Borden took an axe and gave her mother forty whacks. But

It would, certainly, be easy to look at the poverty-row production values here, and dismiss this contemptuously as a bad film. I mean, the very first shot supposedly sets the scene at the infamous New England house in 1892, where Lizzie Borden took an axe and gave her mother forty whacks. But  Oh, be afraid… Be

Oh, be afraid… Be  I am a loner. A destroyed woman. A woman destroyed by people… I have a choice – to kill myself or to kill others. I choose TO PAY BACK MY HATERS. It would be too easy to leave this world as an unknown suicide victim. Society is too indifferent, rightly so. My verdict is: I, Olga Hepnarová, the victim of your bestiality, sentence you to death.

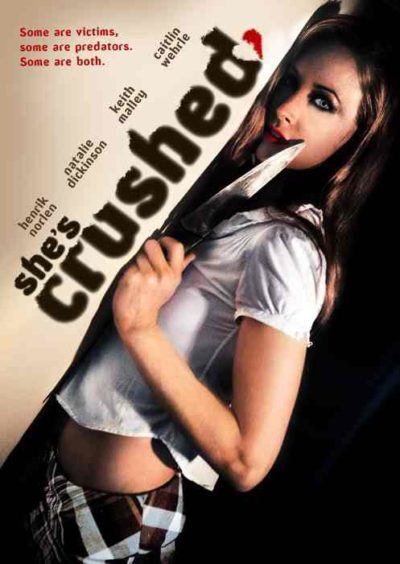

I am a loner. A destroyed woman. A woman destroyed by people… I have a choice – to kill myself or to kill others. I choose TO PAY BACK MY HATERS. It would be too easy to leave this world as an unknown suicide victim. Society is too indifferent, rightly so. My verdict is: I, Olga Hepnarová, the victim of your bestiality, sentence you to death. Playing somewhat like a more brutal version of Fatal Attraction, this sees Ray (Norlén) help out the girl next door, Tara (Dickinson) with some heavy suitcases she’s trying to move into her car. From this eventually stems a one-night stand between the pair, made all the more unfortunate by Ray’s girlfriend, Maddy (Wehrle) being stranded by the side of the road with a flat, while the pair do the dirty deed. Ray then discovers Tara’s darker side: and when I say “darker side”, I mean she makes Alex Forrest of Fatal Attraction look like a bunny-boiling beginner. With the aid of a condom from their dangerous liaison, she frames him for the rape/murder of his boss, forcing him to help her get rid of the body. And Tara is only getting warmed up. Wait until she gets her hands on Maddy…

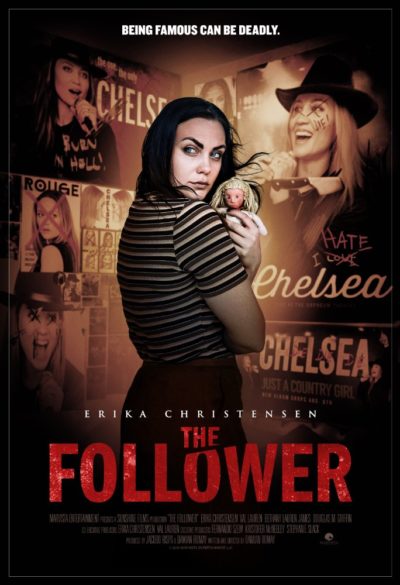

Playing somewhat like a more brutal version of Fatal Attraction, this sees Ray (Norlén) help out the girl next door, Tara (Dickinson) with some heavy suitcases she’s trying to move into her car. From this eventually stems a one-night stand between the pair, made all the more unfortunate by Ray’s girlfriend, Maddy (Wehrle) being stranded by the side of the road with a flat, while the pair do the dirty deed. Ray then discovers Tara’s darker side: and when I say “darker side”, I mean she makes Alex Forrest of Fatal Attraction look like a bunny-boiling beginner. With the aid of a condom from their dangerous liaison, she frames him for the rape/murder of his boss, forcing him to help her get rid of the body. And Tara is only getting warmed up. Wait until she gets her hands on Maddy… Country singer Chelsea Angel (Christensen) announces to her fanbase that’s she taking a time-out from touring and recording – not least because of her recently-discovered pregnancy. Her flight home crashes in the middle of nowhere, and she wakes up to find herself chained up in a remote cabin, along with another survivor, Evelyn (James). Except, it soon turns out that Evelyn isn’t the innocent air hostess she initially appears. She’s Chelsea’s most obsessive and dedicated fan, who was actually responsible for the plane going down. And now, she has the object of her affection – not to mention, her unborn baby – all to herself, for some quality time, in which she can address Chelsea’s new style, with which Evelyn is not happy. Meanwhile, the singer’s boyfriend, Dillon (Lauren), and the guy in charge of her fan-club, Frank (Kirkpatrick), are trying to figure out where Chelsea has gone, following the online trail Evelyn left behind.

Country singer Chelsea Angel (Christensen) announces to her fanbase that’s she taking a time-out from touring and recording – not least because of her recently-discovered pregnancy. Her flight home crashes in the middle of nowhere, and she wakes up to find herself chained up in a remote cabin, along with another survivor, Evelyn (James). Except, it soon turns out that Evelyn isn’t the innocent air hostess she initially appears. She’s Chelsea’s most obsessive and dedicated fan, who was actually responsible for the plane going down. And now, she has the object of her affection – not to mention, her unborn baby – all to herself, for some quality time, in which she can address Chelsea’s new style, with which Evelyn is not happy. Meanwhile, the singer’s boyfriend, Dillon (Lauren), and the guy in charge of her fan-club, Frank (Kirkpatrick), are trying to figure out where Chelsea has gone, following the online trail Evelyn left behind.

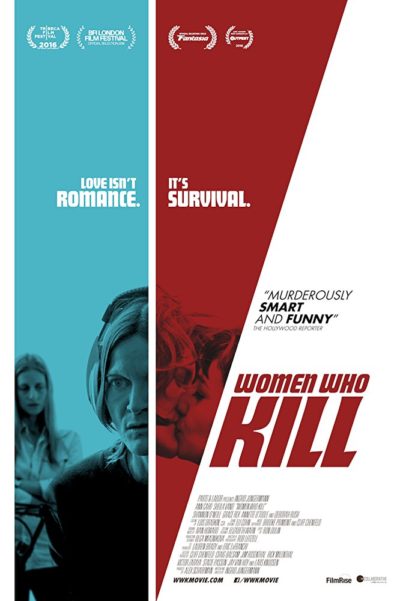

When I told Chris the title of this one, I swear you could hear her eyes rolling at the mere thought of it. But by the end, even she had to admit to having been won over by its dark charms. Most obviously is the sense of black humour which isn’t just dry, it’s as arid as the Atacama Desert. Morgan (Jungermann) and Jean (Carr) are fascinated by female serial killers, running a podcast on the topic which has acquired its own, unique fanbase. Morgan falls for Simone (Vand), a colleague at the food co-operative where she works. But Jean – who is also Morgan’s ex – can’t help thinking there is something seriously off with Simone.

When I told Chris the title of this one, I swear you could hear her eyes rolling at the mere thought of it. But by the end, even she had to admit to having been won over by its dark charms. Most obviously is the sense of black humour which isn’t just dry, it’s as arid as the Atacama Desert. Morgan (Jungermann) and Jean (Carr) are fascinated by female serial killers, running a podcast on the topic which has acquired its own, unique fanbase. Morgan falls for Simone (Vand), a colleague at the food co-operative where she works. But Jean – who is also Morgan’s ex – can’t help thinking there is something seriously off with Simone. The film never tries to hide the fact that Jessica is nutty as a fruitcake. As a result, its plotting is instead very much concerned just with getting the story from Point A to B, offering few surprises. I’m not exactly convinced by the “Based on a true story” claim here. And let’s not even start with the police procedures depictede: let’s just say, Stillwater PD could use some re-training, and move on. Yet the pleasures outweighed the deficiencies; in particular, as mentioned, watching the mousy Faith and psychotic glam-girl Jessica face off. The latter gets most of the cinematic highlights, vamping it up to great effect. Witness, for example, her hyper-ventilating in order to place a convincingly panicked phone call to her lover. Guess all Jessica’s acting classes finally paid off!

The film never tries to hide the fact that Jessica is nutty as a fruitcake. As a result, its plotting is instead very much concerned just with getting the story from Point A to B, offering few surprises. I’m not exactly convinced by the “Based on a true story” claim here. And let’s not even start with the police procedures depictede: let’s just say, Stillwater PD could use some re-training, and move on. Yet the pleasures outweighed the deficiencies; in particular, as mentioned, watching the mousy Faith and psychotic glam-girl Jessica face off. The latter gets most of the cinematic highlights, vamping it up to great effect. Witness, for example, her hyper-ventilating in order to place a convincingly panicked phone call to her lover. Guess all Jessica’s acting classes finally paid off! “Post-horror” is now, apparently, A Thing. It refers to horror films that subvert the traditional tropes and style of the genre in some way. Though based on the so-tagged example of it I’ve seen, the main subversion appears to be “not being frightening.” I think there’s a spot of pretension mixed in as well, since horror is generally regarded as marginally above pornography in terms of critical appreciation. By calling it something else, this gives those who turn their nose up at “horror” a chance to appreciate it. But it’s a bit of a double-edged sword for marketing, because you’re as likely to lose fans of “true” horror, who have been burned badly by films riding on the genre’s coat-tails.

“Post-horror” is now, apparently, A Thing. It refers to horror films that subvert the traditional tropes and style of the genre in some way. Though based on the so-tagged example of it I’ve seen, the main subversion appears to be “not being frightening.” I think there’s a spot of pretension mixed in as well, since horror is generally regarded as marginally above pornography in terms of critical appreciation. By calling it something else, this gives those who turn their nose up at “horror” a chance to appreciate it. But it’s a bit of a double-edged sword for marketing, because you’re as likely to lose fans of “true” horror, who have been burned badly by films riding on the genre’s coat-tails.