Literary rating: ★★★★★

Kick-butt quotient: ☆☆½

Theoretically, this book by Canadian author Wayland Drew is the novelization of the 1988 movie Willow. However, it’s not based directly on the movie itself, but on Bob Dolman’s screenplay (which was itself developed from a guiding storyline written by George Lucas). Much of this screenplay was omitted –and some of it apparently changed, usually to condense and simplify the dialogue and action– in filming the actual movie, and one of the stars (Val Kilmer) ad-libbed most of his dialogue. So the movie actually differs significantly from the book; the latter is much richer in world-building and character development and has a number of significant events that aren’t in the former, and that help to explain some character’s attitudes and choices that are only weakly explained in the film. This means that the relationship of the two is more like that of a movie adapted from a book than that of a typical novelization. It also means it’s harder to identify Drew’s individual modifications and contributions than it would be with most novelizations.

Theoretically, this book by Canadian author Wayland Drew is the novelization of the 1988 movie Willow. However, it’s not based directly on the movie itself, but on Bob Dolman’s screenplay (which was itself developed from a guiding storyline written by George Lucas). Much of this screenplay was omitted –and some of it apparently changed, usually to condense and simplify the dialogue and action– in filming the actual movie, and one of the stars (Val Kilmer) ad-libbed most of his dialogue. So the movie actually differs significantly from the book; the latter is much richer in world-building and character development and has a number of significant events that aren’t in the former, and that help to explain some character’s attitudes and choices that are only weakly explained in the film. This means that the relationship of the two is more like that of a movie adapted from a book than that of a typical novelization. It also means it’s harder to identify Drew’s individual modifications and contributions than it would be with most novelizations.

Regardless of the prehistory of the book’s text, though, the finished novel is a fine work of epic fantasy, with well-developed characters, a stirring plot that doesn’t have logical holes, and vivid prose. In general conception, it owes something to Tolkien’s monumental Lord of the Rings series –but few works of post-Tolkien epic fantasy do not, and it has its own distinct premise, plot, characteristics and flavor; any literary influence is simply that, not slavish dependence. Like Sauron, Bavmorda is a power-freak magic-wielder hungry for world domination; but where Sauron is an impersonal, off-stage evil force, Bavmorda is a fully human character we see up close and personal, in all her ugly glory. Drew’s short-statured Nelwyn race has some general similarities to hobbits, and perhaps more to dwarves; but in the final analysis, they’re neither, a race and culture all their own. (And the basic structure of a quest narrative in fantasy goes back long before Tolkien, as do other archetypes that appear here.) But like the LOTR saga, it has a very clear conflict of good and evil, and a recurring theme of the necessity and important consequences of the moral choices we’re called to make and the responsibilities we’re called to shoulder, whether we see ourselves as well-qualified heroic types or not.

Lucas’ influence is evident in a few places, where the Mystery of magic is presented in terms vaguely reminiscent of the Force in his Star Wars saga (the kind of thing Francis Schaeffer referred to as “contentless mysticism”), but this is a minor note that has no real significance for the storyline. A more prominent (and more positive) theme is the strong affection for the natural world that’s evident, with the idea that good people care about the latter, while evil results in defilement and destruction of nature. (This is brought out much more in the book than in the movie.) The book is also grittier and more violent than the movie in places, but it has no bad language (Madmartigan’s h-words in the film resulted from Kilmer’s ad-libbing) and no real sexual content, beyond the implication of womanizing by Madmartigan with an innkeeper’s wife at one point. (That aspect of his character isn’t glorified, and is explained as a reaction to an earlier event in his past.)

The action-heroine aspect of the book is embodied in the character of Sorsha (played in the movie by Joanne Whalley), the most important female character in the tale. She’s Bavmorda’s daughter, raised not to question her mother –but there’s another side to her heritage, too. Her moral journey, and the choice before her, will be one of those most central to the book. She’s also definitely raised as a warrior, really comfortable only in battle, in the camp or on the march, or in the hunt for dangerous game, thoroughly accustomed to handling weapons (she sleeps with a dagger under her pillow), and as tough as nails; we hardly ever see her out of her armor. For fans of the action-female motif, the one complaint here is that she doesn’t have much in the way of actual fighting scenes –just a couple in the entire book, although she acquits herself bravely and capably in both of them. It’s arguably a pity that the plot here didn’t allow more scope for the display of her butt-kicking abilities.

In a fantasy genre that’s overrun by bloated series, this one also has the advantage of being a stand-alone book with a contained storyline and a clear-cut resolution. Lucas actually intended to make sequels to the film, but never did; instead, he wrote a series of follow-up books, the Chronicles of the Shadow War. But these are set after the events here, and aren’t directly related to them, or at least that’s my impression –I’ve never read them. (That’s why Goodreads labeled the book “Chronicles of the Shadow War 0,” rather than giving it a number as an actual part of the sequence.) So this would be a great choice for fantasy readers who don’t want to commit to a multi-volume series! But it’s a solid, rewarding read for any epic fantasy fan.

Author: Wayland Drew

Publisher: Ballantine Books, available through Amazon, currently only as a printed book.

A version of this review previously appeared on Goodreads.

This series opener is one that was been on my radar for a long time, so I was delighted to finally read it last year! Although I’m a science fiction fan, I’m not generally attracted to military SF, which of course this is. But that’s mostly because my impression is that much of that sub-genre concentrates heavily on futuristic military hardware, to the neglect of the human element (and I think the human element is what good literature is all about). But that’s not a problem here. To be sure, there’s futuristic military hardware, and techno-babble (see below). But the human element, and a rousing tale of human adventure, is the core of the book.

This series opener is one that was been on my radar for a long time, so I was delighted to finally read it last year! Although I’m a science fiction fan, I’m not generally attracted to military SF, which of course this is. But that’s mostly because my impression is that much of that sub-genre concentrates heavily on futuristic military hardware, to the neglect of the human element (and I think the human element is what good literature is all about). But that’s not a problem here. To be sure, there’s futuristic military hardware, and techno-babble (see below). But the human element, and a rousing tale of human adventure, is the core of the book. “Ilona Andrews” is the pen name of a husband-and-wife author team; her first name really is Ilona. (There’s some confusion about his; “About the Authors” in the edition I read gives it as Andrew, but a comment in the extra material uses Gordon, as does the author page on Goodreads. Possibly Andrew Gordon?) They’ve attained considerable success with their urban fantasy Kate Daniels series. Since I’m a fan of both supernatural fiction and strong, kick-butt heroines, it isn’t surprising that the series had been on my radar for a long time before I read this opening volume, as a buddy read with a friend. It didn’t disappoint!

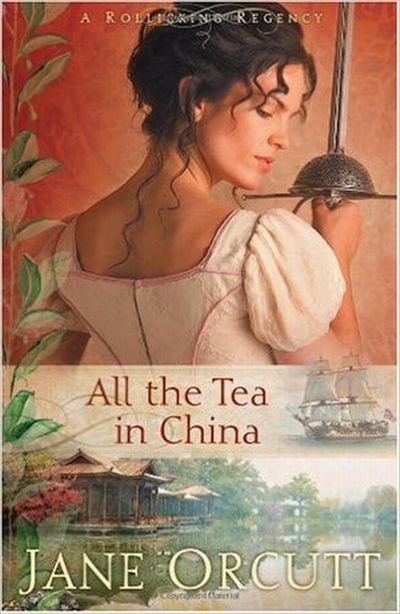

“Ilona Andrews” is the pen name of a husband-and-wife author team; her first name really is Ilona. (There’s some confusion about his; “About the Authors” in the edition I read gives it as Andrew, but a comment in the extra material uses Gordon, as does the author page on Goodreads. Possibly Andrew Gordon?) They’ve attained considerable success with their urban fantasy Kate Daniels series. Since I’m a fan of both supernatural fiction and strong, kick-butt heroines, it isn’t surprising that the series had been on my radar for a long time before I read this opening volume, as a buddy read with a friend. It didn’t disappoint! When I saw this book at a yard sale a few years ago, the captivating picture of a sword-wielding lady on the cover, coupled with the knowledge that the book is a romance by an evangelical Christian author, convinced me that this read would be right up my wife’s alley. I wasn’t wrong; she was initially skeptical of the historical setting (being more into modern settings), but once she got into it, she “couldn’t put it down.” She in turn recommended it to me; and obviously my reaction was positive as well!

When I saw this book at a yard sale a few years ago, the captivating picture of a sword-wielding lady on the cover, coupled with the knowledge that the book is a romance by an evangelical Christian author, convinced me that this read would be right up my wife’s alley. I wasn’t wrong; she was initially skeptical of the historical setting (being more into modern settings), but once she got into it, she “couldn’t put it down.” She in turn recommended it to me; and obviously my reaction was positive as well!