Literary rating: ★★★★★

Kick-butt quotient: ☆☆☆☆½

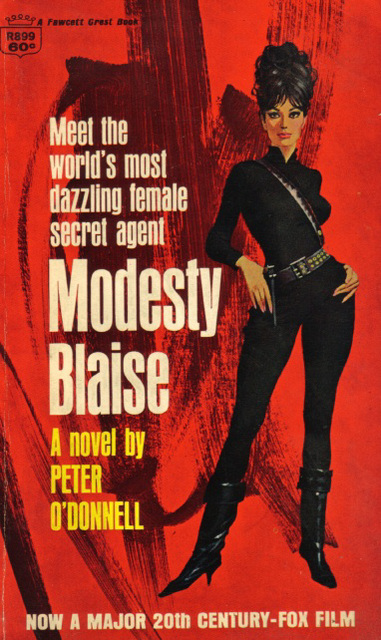

British author Peter O’Donnell created the iconic character of Modesty Blaise in 1963 as the heroine of an action adventure comic strip. He didn’t do the art work for the strip (that was done by four successive artists altogether), but he was responsible for the storylines and printed matter during the whole 38-year run, continuing until 2001. (These original strips are currently being reprinted as a series of graphic novels.) It quickly proved popular enough that 20th-Century Fox enlisted him to write a screenplay for a spin-off movie, which he did. However, he approached the character and the project seriously; and the filmmakers decided that they wanted to produce a parody of the James Bond films instead.

British author Peter O’Donnell created the iconic character of Modesty Blaise in 1963 as the heroine of an action adventure comic strip. He didn’t do the art work for the strip (that was done by four successive artists altogether), but he was responsible for the storylines and printed matter during the whole 38-year run, continuing until 2001. (These original strips are currently being reprinted as a series of graphic novels.) It quickly proved popular enough that 20th-Century Fox enlisted him to write a screenplay for a spin-off movie, which he did. However, he approached the character and the project seriously; and the filmmakers decided that they wanted to produce a parody of the James Bond films instead.

So, they brought in another writer to rework his screenplay, and ended up only keeping one sentence of it. Surprisingly, though, they asked O’Donnell, not his replacement, to do the novelization. He did –but he used his screenplay as the basis. That became the book I’m reviewing here, which was published in 1965 and sparked a long-running series of novels and stories, all with original plots distinct from those of the comic strips. (Meanwhile, the movie, with its caricature of Modesty in the main role, hit the screens in 1966, but failed to spark any fan enthusiasm comparable to what the books and comics generated.)

O”Donnell’s Modesty is a fascinating, complex and layered character, with an unusual back-story that’s provided in its basics at the beginning of this book, but fleshed out more as the tale unfolds. Born about 1939 –she doesn’t know exactly when, nor what her real name and nationality is– she was orphaned as a small child in the chaos and atrocities of World War II, and wandered alone through the Balkans and Middle East, sometimes living in refugee or DP camps. Exposed to a lot of danger and brutality, she survived against all odds because she learned to defend herself and to develop a tough, pragmatic mentality. As a tween, she was mentored by another refugee, a former university professor (whom she protected, rather than the other way around) who taught her a great deal; intelligent and gifted with a good memory, she’s well-educated as a result.

Winding up in Tangier at 17, she soon succeeded to the leadership of a criminal gang, and built it into a substantial international organization, the Network, that engaged in art and jewel thefts, currency manipulations, smuggling, and intelligence brokering. She did NOT, however, engage in drug or sex trafficking (and sometimes provided the authorities with tips that enabled them to bust drug operations); her criminal activities violated the law, but never her own personal moral code and sense of honor. (It was during her Network days that she forged her abiding friendship with Willie Garvin, a skilled knife-fighter whose life had pretty much hit bottom until she saw his potential and recruited him; he would become her lieutenant and faithful sidekick.) Having amassed her goal of half a million pounds sterling by the time she was about 25, she turned the Network over to its regional bosses and she and Willie (also wealthy by that time) retired to a quiet life in England.

The book opens about a year later, when she’s bored and restive, increasingly aware that she’s psychologically geared to find fulfillment and purpose in high-risk physical action, and doesn’t feel really alive when she’s vegetating without it. At this point, she’s approached by Sir Gerald Tarrant, head of British Intelligence (who did business with her, through Willie, when she was brokering items of information that interested the British government). As partial payment to a Middle Eastern sheik for an oil concession, Britain is shipping ten million pounds worth of diamonds from South Africa to Beirut –and there are rumors that the secrecy of the shipment has been compromised, and that someone may be out to steal it. Being aware of Modesty’s unique wide knowledge of, and contacts in, the international underworld, Tarrant would like her to check this out for him. First, though, she’ll have another priority on the agenda –rescuing Willie (also bored and restive) from the South American prison where he’s awaiting execution, having been a mercenary on the losing side in a civil war.

O’Donnell is a master of characterization; not just Modesty and Willie, but all of the secondary characters here too, are wonderfully wrought, full-orbed and realistic. The plotting is taut and well-paced, with no unnecessary filler, and there’s a real sense of danger and challenge. It’s clear that the author has a very good working knowledge of traditional Arab culture, which adds texture here. Unlike Ian Fleming, he doesn’t go in for far-fetched gadgetry, but he does endow his heroine and hero with some believable gadgets and an ability to secrete them on their person. He writes action scenes that are clear, vivid and gripping; and he sets his action in the context of a moral framework –recognizable good is pitted here against genuine evil, and O’Donnell makes us root wholeheartedly for the former and despise the latter. Modesty herself is no plaster saint; I didn’t approve of everything she’s done in her life, or every aspect of her lifestyle now. But I could understand her motivations, and didn’t have any trouble liking and respecting her as a heroine –she has a lot of very real virtues, is a born leader and as valiant a fighter as ever lived, cares about others and treats them decently, and respects innocent life (and will spare adversaries’ lives at times when some people in her shoes probably wouldn’t).

O’Donnell is a master of characterization; not just Modesty and Willie, but all of the secondary characters here too, are wonderfully wrought, full-orbed and realistic. The plotting is taut and well-paced, with no unnecessary filler, and there’s a real sense of danger and challenge. It’s clear that the author has a very good working knowledge of traditional Arab culture, which adds texture here. Unlike Ian Fleming, he doesn’t go in for far-fetched gadgetry, but he does endow his heroine and hero with some believable gadgets and an ability to secrete them on their person. He writes action scenes that are clear, vivid and gripping; and he sets his action in the context of a moral framework –recognizable good is pitted here against genuine evil, and O’Donnell makes us root wholeheartedly for the former and despise the latter. Modesty herself is no plaster saint; I didn’t approve of everything she’s done in her life, or every aspect of her lifestyle now. But I could understand her motivations, and didn’t have any trouble liking and respecting her as a heroine –she has a lot of very real virtues, is a born leader and as valiant a fighter as ever lived, cares about others and treats them decently, and respects innocent life (and will spare adversaries’ lives at times when some people in her shoes probably wouldn’t).

At one point, O’Donnell makes use of a double coincidence in his plotting, which some critics might fault him for. (But that personally didn’t bother me much; I ascribed it to the action of providence.) And while he drops the names of various firearms models to lend verisimilitude to his narrative, he makes a couple of bloopers in his treatment of guns. Also, he describes technical processes at places in the narrative in more detail than I would (I have a low tolerance for that kind of thing), but he usually has a good reason to, and does it with reasonable clarity; some fans will actually regard this as a strength of the writing. One major character displays some sexist attitudes, but I didn’t think O’Donnell was sharing in or justifying them, just realistically depicting the way many males in 1965 thought (and still do).

There’s a high body count here, but the violence is handled quickly and cleanly; while some of the villains are sadists, O”Donnell isn’t. There’s some bad language, and a certain amount of religious profanity, but no obscenity. While there’s no explicit sex, it’s made clear that unmarried sex took place a few times, and will again; Willie and Modesty are single, but not celibate. (Their relationship with each other, though, is perfectly chaste and Platonic –they genuinely do love each other, and would die for each other, but as true friends, not as erotic partners.)

In this book, it’s noted in passing that Modesty has been raped twice in her life. As it stands, that’s just a reflection of the tragic fact that women in our world often do face a lot of sexual violence; and she isn’t defined by the experience, and doesn’t have a victim mentality that allows it to permanently scar her life, which is positive modeling. But I’m told by other readers that in the other books of the series (though not the comics) Modesty tends to be raped quite frequently. To me, that’s a disturbing amount of sexual violence for one character to have to undergo; and it does seem like a morbid overuse of the motif. But that said, I’m still invested enough in this heroine and her future adventures to continue reading the series!

Author: Peter O’Donnell

Publisher: Souvenir Press, available through Amazon, currently only as a printed book.

A version of this review previously appeared on Goodreads.

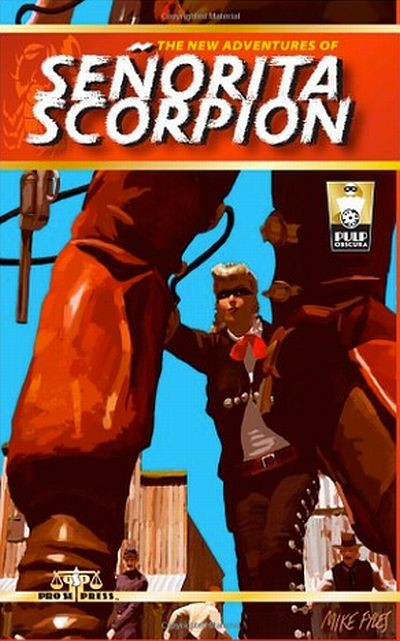

Action adventure fiction, in the pulp era, tended to be a male-dominated field; the writers and readers were overwhelmingly male, and the protagonists having the adventures and engaging in the derring-do tended to be correspondingly male. The culture of that day had deep-rooted stereotypes about the unfitness of the “weaker sex” for strenuous physical challenges, and about the inappropriateness of combat as a role for females who were supposed to be naturally gentle and demure. But there were writings that bucked these assumptions, particularly in the Western genre. Senorita Scorpion, the creation of Les Savage, Jr. (1922-1958), wasn’t actually the first pistol-packing cowgirl to be featured in the Western pulps of the 30s and 40s; but she proved to be the most popular, one of the most unique, and probably the subject of the longest running and thickest corpus of material of any of these fictional ladies: seven stories, originally published in Action Stories from 1944-49. Through its Altus Press imprint, (CreateSpace is just the printing service) Pro Se Press seeks to bring the best fiction of the early modern pulp magazine era back into print, in book form now, for a new generation of fans. These stories (plus one by Emmett McDowell, which used the Senorita Scorpion name for an entirely different character) were a felicitous choice for one of their first projects, in two volumes.

Action adventure fiction, in the pulp era, tended to be a male-dominated field; the writers and readers were overwhelmingly male, and the protagonists having the adventures and engaging in the derring-do tended to be correspondingly male. The culture of that day had deep-rooted stereotypes about the unfitness of the “weaker sex” for strenuous physical challenges, and about the inappropriateness of combat as a role for females who were supposed to be naturally gentle and demure. But there were writings that bucked these assumptions, particularly in the Western genre. Senorita Scorpion, the creation of Les Savage, Jr. (1922-1958), wasn’t actually the first pistol-packing cowgirl to be featured in the Western pulps of the 30s and 40s; but she proved to be the most popular, one of the most unique, and probably the subject of the longest running and thickest corpus of material of any of these fictional ladies: seven stories, originally published in Action Stories from 1944-49. Through its Altus Press imprint, (CreateSpace is just the printing service) Pro Se Press seeks to bring the best fiction of the early modern pulp magazine era back into print, in book form now, for a new generation of fans. These stories (plus one by Emmett McDowell, which used the Senorita Scorpion name for an entirely different character) were a felicitous choice for one of their first projects, in two volumes. From this beginning, the first four stories proceed in a chronological arc; each is self contained, but the following ones build on the preceding ones in terms of character and situational development, so that what we have is a genuine story cycle. In the later three stories, the chronological relationship to the rest of the corpus isn’t as clear, except that they all take place after the events of the first story, and that “Lash of the Six-Gun Queen” is set near the end of the decade. Savage makes statements inconsistent in details with what he wrote earlier in one story, and another tale also gives some evidence of forgetfulness on his part. The rest of the Douglas clan simply disappears in the later stories, and their unique sociological circumstances aren’t explored at all, while the Santiago Ranch functions about like a set or a piece of furniture; there’s not much attention to its fortunes or the practicalities of running it. Elgera’s supposedly well-known skill at cards is only brought out in “Brand of the Gallows-Ghost,” and never mentioned elsewhere.

From this beginning, the first four stories proceed in a chronological arc; each is self contained, but the following ones build on the preceding ones in terms of character and situational development, so that what we have is a genuine story cycle. In the later three stories, the chronological relationship to the rest of the corpus isn’t as clear, except that they all take place after the events of the first story, and that “Lash of the Six-Gun Queen” is set near the end of the decade. Savage makes statements inconsistent in details with what he wrote earlier in one story, and another tale also gives some evidence of forgetfulness on his part. The rest of the Douglas clan simply disappears in the later stories, and their unique sociological circumstances aren’t explored at all, while the Santiago Ranch functions about like a set or a piece of furniture; there’s not much attention to its fortunes or the practicalities of running it. Elgera’s supposedly well-known skill at cards is only brought out in “Brand of the Gallows-Ghost,” and never mentioned elsewhere. Full disclosure up front: the author and I are in a couple of Goodreads groups together, so I was aware of his debut novel; and I knew he’d offered a free review e-copy to group members. I didn’t request one, since I prefer to read in print format; but on the recommendation of my friend David Wittlinger, I did put my name in for the paperback Goodreads giveaway (which is still ongoing!). When Bran became aware of my preference for paper, he kindly gifted me with a paperback copy, which I really appreciate. His openness to honest feedback is also appreciated; he made it clear from the outset that he’d appreciate even a bad review as long as it was honest and provided him with feedback. It didn’t take me long to read enough to tell that my review wasn’t going to be a bad one!

Full disclosure up front: the author and I are in a couple of Goodreads groups together, so I was aware of his debut novel; and I knew he’d offered a free review e-copy to group members. I didn’t request one, since I prefer to read in print format; but on the recommendation of my friend David Wittlinger, I did put my name in for the paperback Goodreads giveaway (which is still ongoing!). When Bran became aware of my preference for paper, he kindly gifted me with a paperback copy, which I really appreciate. His openness to honest feedback is also appreciated; he made it clear from the outset that he’d appreciate even a bad review as long as it was honest and provided him with feedback. It didn’t take me long to read enough to tell that my review wasn’t going to be a bad one!