★★★

“CSI: Shacheng”

The heroine of this period piece us Sima Feiyan (Shang), a roaming law officer, currently in the process of tracking down a gang of four criminals. She successfully nails three in the opening sequence, and tracks the fourth to the city of Shacheng. There, she meets up with old friend Wu Jing Ping (Qi) and his son, Jingbin (Zhang R.B.). She gets diverted by the case of a missing person, which takes to a nearby inn, where a host of suspicious figures are gathering. Turns out, there’s a lost city reported to be accessible only once every 49 years, and treasure hunters are gathering for the chase. Unsurprisingly, this ends up being connected to the missing person, the criminal she seeks and even the Wu family.

The heroine of this period piece us Sima Feiyan (Shang), a roaming law officer, currently in the process of tracking down a gang of four criminals. She successfully nails three in the opening sequence, and tracks the fourth to the city of Shacheng. There, she meets up with old friend Wu Jing Ping (Qi) and his son, Jingbin (Zhang R.B.). She gets diverted by the case of a missing person, which takes to a nearby inn, where a host of suspicious figures are gathering. Turns out, there’s a lost city reported to be accessible only once every 49 years, and treasure hunters are gathering for the chase. Unsurprisingly, this ends up being connected to the missing person, the criminal she seeks and even the Wu family.

While more or less shamelessly lifting elements from sources as diverse as Sherlock Holmes, Dragon Inn and Indiana Jones, as well as the TV show noted above, this Chinese TV movie does so with enough energy and invention of its own to make for an entertaining time. Sima is rather like the great detective, though this “Sherlock” is rather more pugilistic than Conan Doyle’s version – or even Robert Downey’s! She is able to look at a scene and “see” in her mind how things rolled out – hence the CSI comparison – and is accompanied by a plucky (but less talented) sidekick, Ye Zi (Zhang P.Y), basically the Watson to her Holmes. There’s no shortage of action, save perhaps at the end, which was a bit disappointing. Much running around a trap-laden underground complex (coughTempleOfDoomcough!), but not the grandstand climax I wanted.

Up until then, however, it has been genuinely a good bit of fun. It takes a little bit of a while for the story to settle down, yet when it does, it’s a genre mash-up that provides decent value, despite the occasionally ropey bit of green-screen work. Shang has just the right approach to the role. She portrays Sima as possessing a calm demeanour, even when provoked, and as someone takes her job seriously; that makes the viewer take events seriously as well. It’s Ye Zi who generally provides the film’s lighter moments, and gets shunted off to one side for the climax. The action is not bad. It does suffer a little from the hyper-kinetic editing, yet is still capable of being followed. There’s enough invention that the viewer should be willing to cut it some slack, and there certainly no shortage, which helps.

It feels like the pilot episode for a TV series, and does a solid job of establishing the general situation and the characters. This kind of “historical crime investigator” seems to be a mini-trend in the Far East, with franchises such as Detective Dee in China, or the Korean Detective K. This is the first I’ve seen which goes with a woman, and while not perfect, it’s sprightly enough that I’d certainly be interested in seeing more of its heroine.

Dir: Si Shu-bu

Star: Shang Rong, Zhang Pei Yu, Qi Jingbin, Zhang Ren Bo

Having previously read and thoroughly enjoyed, the same author’s

Having previously read and thoroughly enjoyed, the same author’s  Not quite the first film from Kazakhstan I’ve ever seen. That would be

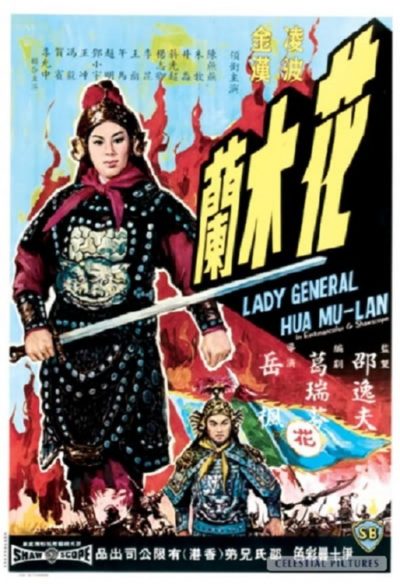

Not quite the first film from Kazakhstan I’ve ever seen. That would be  I probably should have done a bit more research before adding this to the list of versions for review here. I saw a sixties movie made by Shaw Brothers with that title, and presumed there would be kung-fu. Boy, was I wrong. There’s about one significant scene, which pits Mulan (Po) and some of her new army colleagues against each other. And that’s it. Oh, there is a battle between Imperial and invading forces. This might have contained some action, but was so poorly photographed – mostly due to incredibly bad lighting – that it was impossible to tell. What there was, instead, was singing.

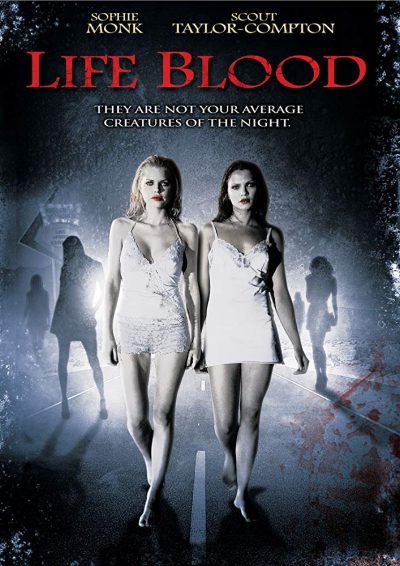

I probably should have done a bit more research before adding this to the list of versions for review here. I saw a sixties movie made by Shaw Brothers with that title, and presumed there would be kung-fu. Boy, was I wrong. There’s about one significant scene, which pits Mulan (Po) and some of her new army colleagues against each other. And that’s it. Oh, there is a battle between Imperial and invading forces. This might have contained some action, but was so poorly photographed – mostly due to incredibly bad lighting – that it was impossible to tell. What there was, instead, was singing. There’s a fascinating idea at the core here. Namely, that vampires were created by God, in order to mitigate mankind’s sin by preying on the most evil examples of humanity. They’re effectively angelic enforcers. The potential in this is great. The execution, however… Well, it largely comes down to two such vampire/angels sitting around a gas station for the majority of the running time. This isn’t the only aspect which is poorly considered. It starts in 1969, when lesbian couple Brooke (Lahiri) and Rhea (Monk) are at a New Year’s party. Brooke kills a rapist, stabbing him (literally) 87 times, and the pair then flee. In the desert, they are visited by God (model Angela Lindvall), who makes Rhea into one of her enforcers.

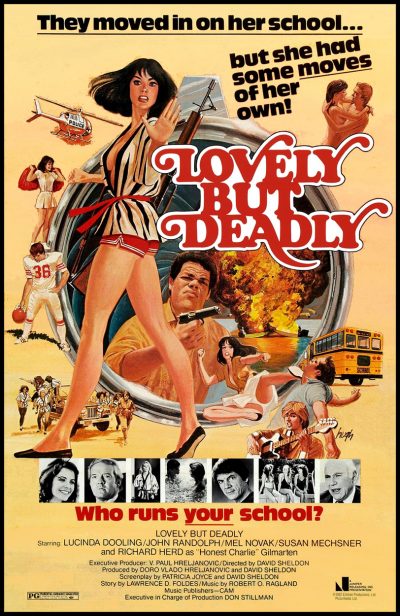

There’s a fascinating idea at the core here. Namely, that vampires were created by God, in order to mitigate mankind’s sin by preying on the most evil examples of humanity. They’re effectively angelic enforcers. The potential in this is great. The execution, however… Well, it largely comes down to two such vampire/angels sitting around a gas station for the majority of the running time. This isn’t the only aspect which is poorly considered. It starts in 1969, when lesbian couple Brooke (Lahiri) and Rhea (Monk) are at a New Year’s party. Brooke kills a rapist, stabbing him (literally) 87 times, and the pair then flee. In the desert, they are visited by God (model Angela Lindvall), who makes Rhea into one of her enforcers. After her brother drowns while high on drugs, Mary Ann “Lovely” Lovitt (Dooling) goes undercover at his school, Pacific Coast High, in order to root out the dealers responsible for his death. She discovers that the problem is far larger than is admitted, with those involved, and includes not just some of the most revered pupils e.g. star players on the football team (and, on more than one occasion, their jealous girlfriends!). A number of adults are also culpable, including leading school boosters, all the way up to leading local businessman ‘Honest Charley’ Gilmarten (Herd). Fortunately, Mary Ann is an expert in martial-arts, so proves more than capable of defending herself when attempts are made to dissuade her from investigating further.

After her brother drowns while high on drugs, Mary Ann “Lovely” Lovitt (Dooling) goes undercover at his school, Pacific Coast High, in order to root out the dealers responsible for his death. She discovers that the problem is far larger than is admitted, with those involved, and includes not just some of the most revered pupils e.g. star players on the football team (and, on more than one occasion, their jealous girlfriends!). A number of adults are also culpable, including leading school boosters, all the way up to leading local businessman ‘Honest Charley’ Gilmarten (Herd). Fortunately, Mary Ann is an expert in martial-arts, so proves more than capable of defending herself when attempts are made to dissuade her from investigating further. It’s one of those weird coincidences. I watched two action heroine flicks last weekend and both, while American, starred actresses who were born in Greece. Really, what are the odds?

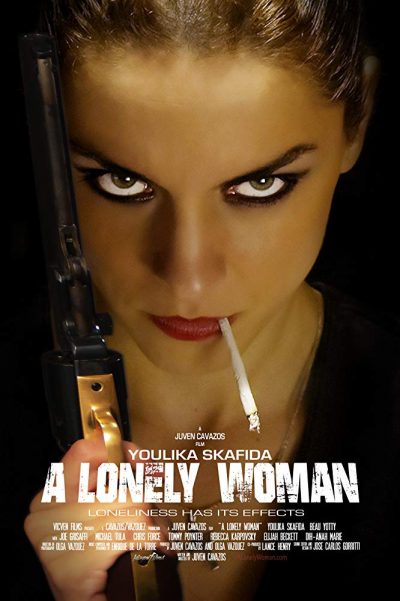

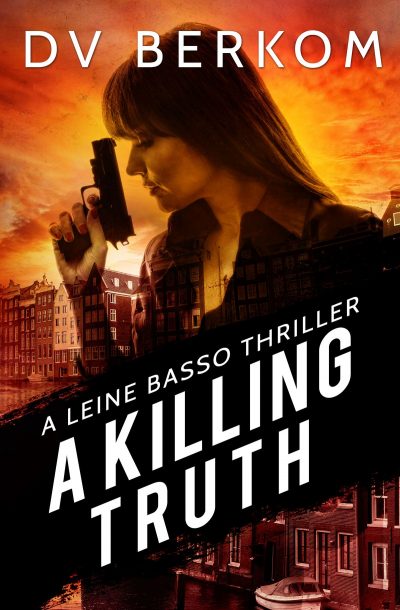

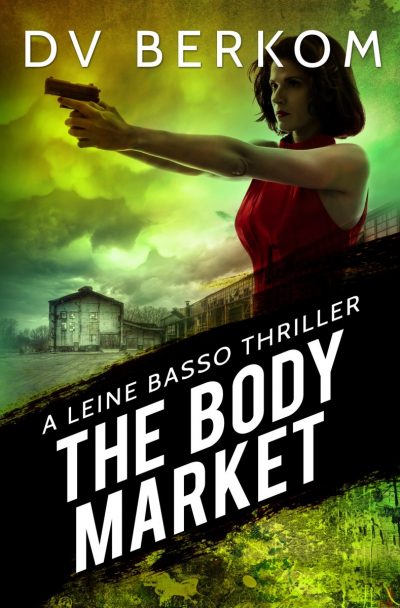

It’s one of those weird coincidences. I watched two action heroine flicks last weekend and both, while American, starred actresses who were born in Greece. Really, what are the odds?  Leine (short for Madeleine) Basso quit her job as a somewhat-sanctioned government assassin, after realizing her boss was using her to carry out off-book, non-sanctioned ops for his personal gain. Oh, and he also tricked her into killing her lover, and b Initially working in private security, she is hired on a reality show, following the murder of a contestant (Book 1: Serial Date) by a serial killer out to make a point. Leine’s daughter is abducted, and it turns out the perpetrator is a shadow from her past, with a grudge.

Leine (short for Madeleine) Basso quit her job as a somewhat-sanctioned government assassin, after realizing her boss was using her to carry out off-book, non-sanctioned ops for his personal gain. Oh, and he also tricked her into killing her lover, and b Initially working in private security, she is hired on a reality show, following the murder of a contestant (Book 1: Serial Date) by a serial killer out to make a point. Leine’s daughter is abducted, and it turns out the perpetrator is a shadow from her past, with a grudge. That’s a technical issue, not particularly relevant to this review, however. To be honest, when I got the first book, I was expecting more globetrotting assassinations, and less stuff more befitting a PI or homicide detective, which is really what the first two books are more like. Things perk up considerably in #3, with Leine having to handle life south of the border; you’ll probably be crossing Mexico off your list of potential destinations by the time you’re done there. They do seem – consciously or not – to become more exotic and international, as they go on. #4 and #5 take place almost exclusively abroad, to the point that I felt a bit sorry for Leine’s boyfriend, who must barely see her!

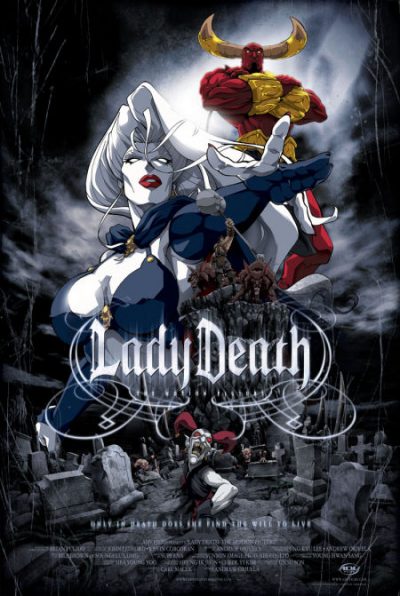

That’s a technical issue, not particularly relevant to this review, however. To be honest, when I got the first book, I was expecting more globetrotting assassinations, and less stuff more befitting a PI or homicide detective, which is really what the first two books are more like. Things perk up considerably in #3, with Leine having to handle life south of the border; you’ll probably be crossing Mexico off your list of potential destinations by the time you’re done there. They do seem – consciously or not – to become more exotic and international, as they go on. #4 and #5 take place almost exclusively abroad, to the point that I felt a bit sorry for Leine’s boyfriend, who must barely see her! My first viewing of this was on a day off from work, when I was down with some sinusy thing, and dosed up on DayQuil. So I chalked my losing interest and drifting off to the meds, and once I felt better, decided this deserved the chance of a re-view. However, the result was still the same: even as a bright-eyed and bushy-tailed viewer, I found attention lapsing. For this animated version of a mature comic, might as well be a He-Man and the Masters of the Universe episode. Which is a shame. I wanted to like it, since the creator of Lady Death, Brian Pulido, is something of a local comics legend here in my adopted home state of Arizona. This should have been better.

My first viewing of this was on a day off from work, when I was down with some sinusy thing, and dosed up on DayQuil. So I chalked my losing interest and drifting off to the meds, and once I felt better, decided this deserved the chance of a re-view. However, the result was still the same: even as a bright-eyed and bushy-tailed viewer, I found attention lapsing. For this animated version of a mature comic, might as well be a He-Man and the Masters of the Universe episode. Which is a shame. I wanted to like it, since the creator of Lady Death, Brian Pulido, is something of a local comics legend here in my adopted home state of Arizona. This should have been better.