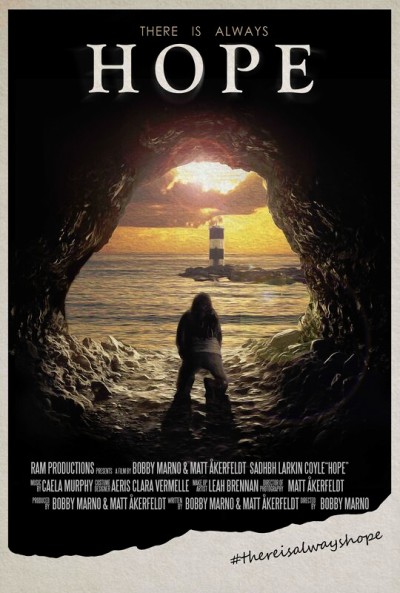

★★

“Hope isn’t necessarily good.”

Hope (Larkin-Coyle) is an aspiring vlogger, though has not yet figured out how to make it pay sufficiently to quit her grindingly dull day job, for a boss who perpetually questions Hope’s commitment. She’s not wrong, because Hope’s heart definitely lives in the outdoors, not at a desk or in a Zoom meeting. Her particular niche of content creation is in wilderness adventures, whether that’s going up mountains, diving underwater or – as in this case – scaling a cliff-face. She then posts the videos online, so that others can live vicariously through her experience. She’s excited for her next trip, which will take her back to a part of Ireland by the ocean, which was a favourite haunt of her late mother.

Hope (Larkin-Coyle) is an aspiring vlogger, though has not yet figured out how to make it pay sufficiently to quit her grindingly dull day job, for a boss who perpetually questions Hope’s commitment. She’s not wrong, because Hope’s heart definitely lives in the outdoors, not at a desk or in a Zoom meeting. Her particular niche of content creation is in wilderness adventures, whether that’s going up mountains, diving underwater or – as in this case – scaling a cliff-face. She then posts the videos online, so that others can live vicariously through her experience. She’s excited for her next trip, which will take her back to a part of Ireland by the ocean, which was a favourite haunt of her late mother.

However, a moment’s inattention leads to disaster, with Hope sent plummeting to the rocks below. When she regains consciousness, she finds her shin bone shattered and sticking out of her leg. With (inevitably!) no cell signal, she is thrown back on her own resources, and will have to make her way out of an increasingly precarious situation, entirely by herself. As you can imagine from this synopsis, it puts a lot of weight on the shoulders of the lead actress, and it’s all a little contrived. Initially, I expected there to be much more of her speaking to the camera, documenting events for her online followers. But the film doesn’t really go that way, favoring a more general voicing of Hope’s inner monologue.

In the main, to be blunt, you are basically watching a woman crawl across rocks for an hour, and I’m probably stating the obvious when I say that this is of limited appeal. There are some inconsistencies which seemed annoying at the time, almost as if whole scenes had been removed. One second, Hope is on a beach. The next, she’s swimming in the water – broken leg and all. Then she’s suddenly marooned in a cave. There’s also character stupidity, such as Hope’s ignorance or wilful disregard for basic survival protocols. However, there’s a third-act twist which, to be fair, goes a long way to explaining what had gone before. On the other hand, you’re left wondering if perhaps the film-makers have sabotaged the entire point with it.

A more definite problem is the sense that there simply is not enough happening here. The fall, presumably for budgetary reasons, is a simple fade to black accompanied by a scream. I will say, the sounds Coyle makes when exploring her wound are legitimately harrowing, and help sell her injury as much as the small but effective effects work on her leg. That takes care of about five minutes, leaving… 93 others, which fall well short of possessing the same degree of intensity. It feels as if the makers were looking to paint a psychological portrait, using the frame of a wilderness survival story. As someone who was expecting a genuine wilderness survival story, I’m left feeling distinctly short-changed, and a little bit cheated.

Dir: Bobby Marno

Star: Sadhbh Larkin Coyle

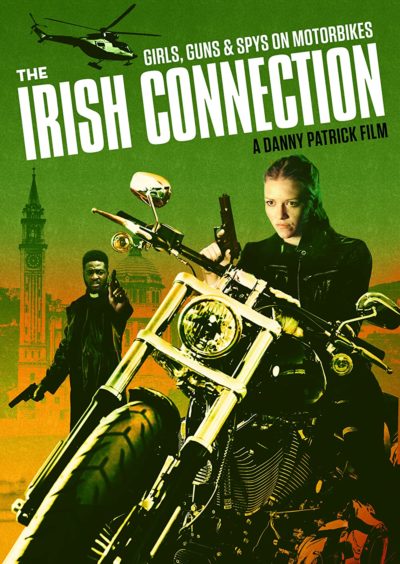

At times this feels more like a fancy dress party than a film. People dressed up as nuns. People dressed up as clowns. People dressed as priests. This probably isn’t surprising, considering that it feels like Patrick is cosplaying as a film-maker. There’s little or no evidence to indicate he knows how to construct a coherent or interesting narrative. Instead, he proceeds by simply dropping in scenes which, I gueaa, are supposed to be “amusing”, without rhyme or reason. I called Aureille the heroine above, though there’s precious little to make her so. I presumed she is supposed to be the “good guy”, because there are no other credible candidates for that role, so she earns it by default.

At times this feels more like a fancy dress party than a film. People dressed up as nuns. People dressed up as clowns. People dressed as priests. This probably isn’t surprising, considering that it feels like Patrick is cosplaying as a film-maker. There’s little or no evidence to indicate he knows how to construct a coherent or interesting narrative. Instead, he proceeds by simply dropping in scenes which, I gueaa, are supposed to be “amusing”, without rhyme or reason. I called Aureille the heroine above, though there’s precious little to make her so. I presumed she is supposed to be the “good guy”, because there are no other credible candidates for that role, so she earns it by default. Made on a shoestring in Ireland, the nicest thing you can say is probably, this doesn’t look as cheap as it was. If only you could say the same for the script, which seems to be trying to be Guy Ritchie, only to end up nearer to Guy Fieri. It’s not a terrible idea, if rather stretching belief. Katelin Ballantine (Doherty) is a film producer, trying to raise funds for her latest movie. To that end, she is hanging out, unwillingly, with sleazeball businessman, Felim Shaw. What she doesn’t know, is he is deep in debt to local mob-boss Edmund Murren (Fleming). He kidnaps them both, forces Katelin to kill her potential investor, then threatens her family to make her continue in her new career as his assassin, alongside former friend and now Murren associate, Henry Furey (Kealy).

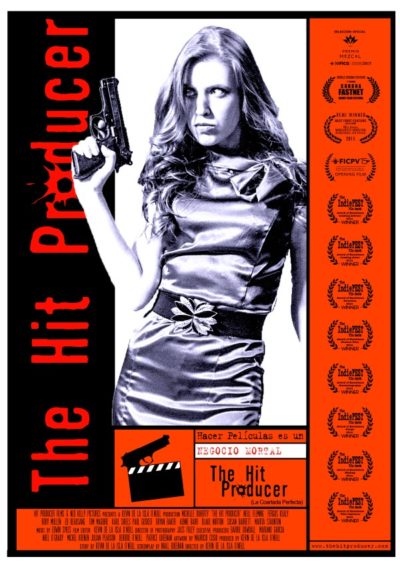

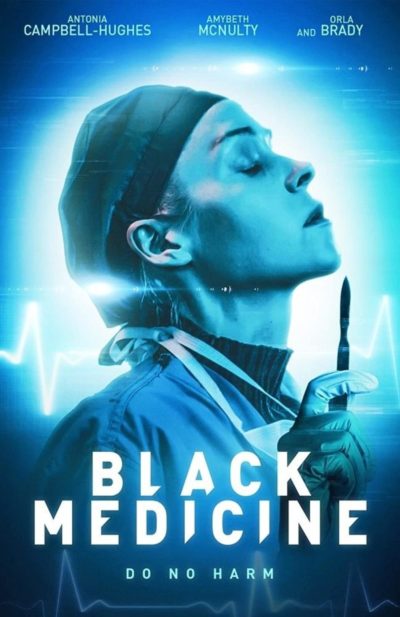

Made on a shoestring in Ireland, the nicest thing you can say is probably, this doesn’t look as cheap as it was. If only you could say the same for the script, which seems to be trying to be Guy Ritchie, only to end up nearer to Guy Fieri. It’s not a terrible idea, if rather stretching belief. Katelin Ballantine (Doherty) is a film producer, trying to raise funds for her latest movie. To that end, she is hanging out, unwillingly, with sleazeball businessman, Felim Shaw. What she doesn’t know, is he is deep in debt to local mob-boss Edmund Murren (Fleming). He kidnaps them both, forces Katelin to kill her potential investor, then threatens her family to make her continue in her new career as his assassin, alongside former friend and now Murren associate, Henry Furey (Kealy). I guess, at its heart, this is the story of two mothers. There’s Jo (Campbell-Hughes), an anaesthetist who has been struck off the medical register, for reasons that are left murky. She’s now practicing her healing arts on the underground market, from patching up dubious stabbing victims, to carrying out unlicensed abortions. Jo lost her daughter to meningitis, and has split from her husband. Then there’s Bernadette (Brady), a wealthy but no less murky character. Her daughter is dying, and in desperate need of a transplant. To that end, Bernadette has kidnapped a young woman, Aine (McNulty), with the intention of using her as an unwilling organ donor, and needs Jo’s help for the operation. But when Aine – who would be about the age of Jo’s daughter had she lived – escapes and hides in the back of the physician’s car, Jo is left with a series of difficult decisions.

I guess, at its heart, this is the story of two mothers. There’s Jo (Campbell-Hughes), an anaesthetist who has been struck off the medical register, for reasons that are left murky. She’s now practicing her healing arts on the underground market, from patching up dubious stabbing victims, to carrying out unlicensed abortions. Jo lost her daughter to meningitis, and has split from her husband. Then there’s Bernadette (Brady), a wealthy but no less murky character. Her daughter is dying, and in desperate need of a transplant. To that end, Bernadette has kidnapped a young woman, Aine (McNulty), with the intention of using her as an unwilling organ donor, and needs Jo’s help for the operation. But when Aine – who would be about the age of Jo’s daughter had she lived – escapes and hides in the back of the physician’s car, Jo is left with a series of difficult decisions.

2020’s first seal of approval goes to this uber-gritty Irish film, starring Sarah Bolger, whose most familiar to us from Into the Badlands. While her GWG creds there are overshadowed by the likes oE Emily Beecham, safe to say Bolger makes up for lost time here. She plays single mother Sarah Collins, who is struggling to come to terms with the recent, unsolved murder of her husband. Barely managing to make ends meet, her life is upended when entry-level criminal Tito (Simpson) breaks in, seeking sanctuary. He has stolen some drugs belonging to top boss Leo (Hogg), and offers Sarah a cut of the proceeds if she’ll act as his safe-house. Very reluctantly, she agrees. Needless to say, it doesn’t go as they plan.

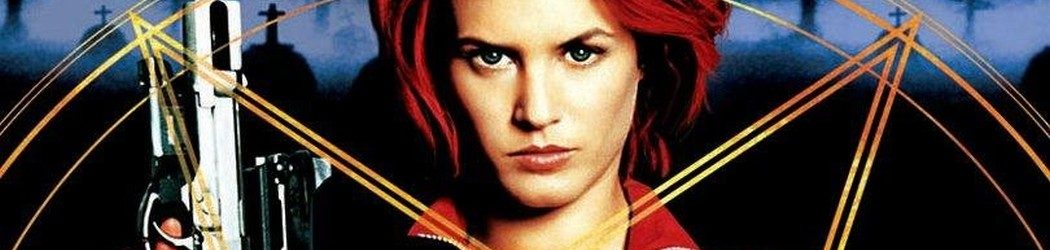

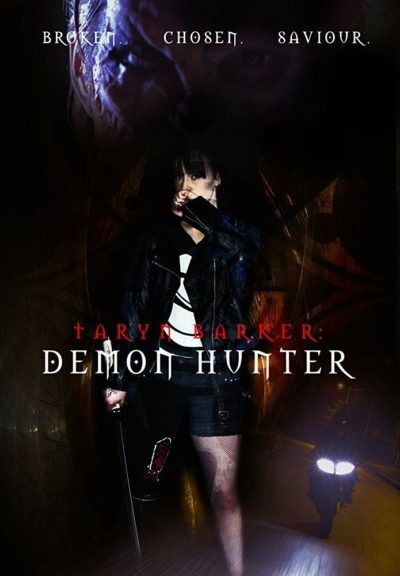

2020’s first seal of approval goes to this uber-gritty Irish film, starring Sarah Bolger, whose most familiar to us from Into the Badlands. While her GWG creds there are overshadowed by the likes oE Emily Beecham, safe to say Bolger makes up for lost time here. She plays single mother Sarah Collins, who is struggling to come to terms with the recent, unsolved murder of her husband. Barely managing to make ends meet, her life is upended when entry-level criminal Tito (Simpson) breaks in, seeking sanctuary. He has stolen some drugs belonging to top boss Leo (Hogg), and offers Sarah a cut of the proceeds if she’ll act as his safe-house. Very reluctantly, she agrees. Needless to say, it doesn’t go as they plan. Behind a remarkably generic and forgettable title sits an entirely reasonable slice of low-budget Irish action-horror. It’s clear creator Kavanagh knows what has gone before, and if the resources here don’t allow her to reproduce them on anything approaching the same scale, she knows her limitations and works well enough within them. Besides, who can resist a film that works a Ramones lyric into its dialogue? Taryn (Hogan) feels responsible for the death of her little sister, abducted and killed on the way home from school. She gets a chance to do something about it, when approached by the mysterious Falstaff (Parle) after her sister’s funeral. He reveals a secret world of demons and sacrifices – Taryn’s sister being one of the latter – and offers Taryn a chance for revenge, if she’ll come and work for him.

Behind a remarkably generic and forgettable title sits an entirely reasonable slice of low-budget Irish action-horror. It’s clear creator Kavanagh knows what has gone before, and if the resources here don’t allow her to reproduce them on anything approaching the same scale, she knows her limitations and works well enough within them. Besides, who can resist a film that works a Ramones lyric into its dialogue? Taryn (Hogan) feels responsible for the death of her little sister, abducted and killed on the way home from school. She gets a chance to do something about it, when approached by the mysterious Falstaff (Parle) after her sister’s funeral. He reveals a secret world of demons and sacrifices – Taryn’s sister being one of the latter – and offers Taryn a chance for revenge, if she’ll come and work for him.