“I couldn’t love a man who commands me – any more than I could love one who lets himself be commanded by me.”

“I couldn’t love a man who commands me – any more than I could love one who lets himself be commanded by me.”

— Jacquotte Delahaye

For the purposes of this article, we are defining “women pirates” somewhat loosely. You don’t necessarily have to be wielding the cutlass yourself, though such a hands-on approach is certainly appreciated. Staying safely on shore and commanding a bunch of scurvy swabs [am I doing this Piratespeak right?] is perfectly fine. However, we do draw the line at plausible deniability. For instance, in the era of Queen Elizabeth I, piracy was barely discouraged if the victims were Spanish, with “privateers” like John Hawkins operating with the more or less tacit approval of the crown. But, at least nominally, it was still a hanging offense.

Among the earliest examples of piratically-inclined ladies was Queen Teuta of Illyria, known as the Terror of the Adriatic, though she was more a commander of pirates than one herself. She inherited the throne of the area which would become 20th-century Yugoslavia, around 230 B.C. after her husband died, and gave local buccaneers the green light to go raiding in her name, up and down the Adriatic. However, these predations eventually brought her to the attention of the Roman Empire, who dropped the hammer on Teuta in no uncertain fashion, sending a 20,000 strong army over for a cup of tea and a chat. She ended up stripped of most of her territories, though was at least allowed to keep her life and, nominally, her title.

Alfhild

Alfhild

The 12th-century work by Danish author Saxo Grammaticus called the Gesta Danorum, was also a source when we covered Viking warrior women a few months back – and, of course, the line between “piracy” and “extremely enthusiastic foraging” is a thin one. But Grammaticus also mentions, mostly in passing, others such as Wigbiorg, Hetha. Wisna and Princess Sela. The last-name was sister to the King of Norway, Koller, and Saxo calls her, “a skilled warrior and experienced in roving.” [She was killed by Horwendil, the father of Hamlet]

The most interesting is perhaps Alfhild [various spellings of her name exist, e.g. Alvid, Awilda], from Volume VII. According to the chronicler, she was such a babe, her father, a King of the Goths called Siward, kept her locked up, protected by snakes – and further decreed that if any suitor tried to reach her and failed, his head would be forfeit. Understandably, this limited her teenage dating exploits. Eventually, one brave warrior, Alf, succeeded. However, Siward still gave his daughter freedom of choice in the matter – and Alfhild promptly spurned his advances, spurred on by her mother:

Alfhild was led to despise the young Dane; whereupon she exchanged woman’s for man’s attire, and, no longer the most modest of maidens, began the life of a warlike rover. Enrolling in her service many maidens who were of the same mind, she happened to come to a spot where a band of rovers were lamenting the death of their captain, who had been lost in war; they made her their rover captain for her beauty, and she did deeds beyond the valour of woman.

But Alf eventually got his girl, though it took “many toilsome voyages” – proving that the term “playing hard to get”, takes on a whole new level of meaning when your fiancee is a Scandinavian pirate queen.

Jeanne de Clisson

Alfhild’s historical existence is uncertain, with Grammaticus writing a long time after her supposed exploits. That isn’t the case for our next seafaring lady, with contemporary French documentation offering supporting evidence. Jeanne was born in 1300, and first married at the age of 12, as was not uncommon for the era. After her husband died, she married again, but to little better end, as this second spouse was executed in 1343, on suspicion of collaborating with the English, against whom France was at war. Jeanne swore revenge on King Philip VI, sold her estates and began attacking his forces across Brittany. When the heat in France got too much, she relocated to England, and with help from King Edward III, created the Black Fleet.

For the next thirteen years, these boats, painted black and with red sails, hunted French ships in the English Channel, killing their crews, but leaving a few alive to spread the legend of “The Lioness of Brittany”, as de Clisson became known. Her reign outlasted Philip, who died in 1350, but Jeanne was clearly having too much fun, and continued her assault. Legend has it she especially enjoyed capturing French noblemen, and would personally behead them with an axe. She eventually married for a third time, and retired from the seas. [Note: she should not be confused with another medieval bad-ass, Jeanne de Montfort, though both operated around the same time, and supported the English in their war against France]

Sayyida al Hurra

Sayyida al Hurra

Moving into the Middle Ages and the 16th century, we see the likes of Irish sea-queen Gráinne Ní Mháille, about whom we wrote previously. But equally notable was this Islamic pirate, whose full name we will only give once, for reasons which will soon be obvious: Sayyida al-Hurra ibn Banu Rashid al-Mandri al-Wattasi Hakima Tatwan. “Sayyida al Hurra” is actually an honorific title, apparently meanimg “the woman sovereign who bows to no superior authority.” She operated particularly around the Straits of Gibraltar between Spain and Morocco, after the last Moorish outpost in Spain fell in 1492. She and her husband relocated to northern Morocco, and ruled over the city of Tétouan, which they had helped rebuild.

Following the death of her husband in 1513, the widow took over the reins, but also used the proceeds from trading to begin assembling her forces. Her fleet set sail in 1520, attacking any Portuguese ships with the misfortune to meet them, and not just looting them, but taking hostages who could be ransomed for even more plunder – much of the evidence for Sayyida comes in the form of documents concerning these negotiations. But, as far as she was concerned, these attacks were as much an act of political rebellion as financial acquisition, harassing the Christians who had driven her and her family out of Granada. Such was her success that she was able to form an alliance with an even more well-known name, Barbarossa, carving up the Mediterranean so that each had their own territory. Her fleet operated for two decades, Spanish papers from 1540 recording a raid on Gibraltar, in which “they took much booty and many prisoners.” She was eventually deposed by her son-in-law two years later, and vanished from the historical record.

Jacquotte Delahaye and Anne Dieu-le-Veut

As we move in to the 17th century, pirate location changes. Previously, it had been based around the centres of civilization – in the apocryphal words of bank robber Willie Sutton, “because that’s where the money is.” But as the era of exploration blossomed, focus shifted toward the arena that would become most linked with pirates in popular culture: the Caribbean, as trade to/from the New World flourished.

These two operated there, and Delahaye was perhaps the first “true” pirate of the modern era, who has become a figure of legend. She was reportedly (let’s just take that word as read in this section!) the daughter of a French father and Haitian mother: the latter died in childbirth, and the former’s murder led to Delahaye’s entry into the world of piracy. She apparently faked her own death to escape those who pursued her, but her subsequent return to the fray earned this redhead the nickname of “Back from the Dead Red”. She is said to have led 100 pirates, and took over an island in 1656, turning it into a “freebooter’s republic”, a mini-Tortuga – she was killed defending it from the Spanish several years later.

Anne Dieu-le-Veut (Anne “God wills it”) appears to have a thing for pirates, marrying three of them. The story goes, she won the heart of the third, Laurens de Graaf, by challenging him to a duel to avenge the death of husband #2. When he accepted, and she wouldn’t back down, he proposed to her, in admiration of her courage. The two operated as equals in the piratical exploits, and attacked English-held Jamaica in 1693, but a couple of years later, Anne and their children were captured by English forces at Port-de-Paix in Haiti. They were held hostage for three years before being released [presumably ransomed] and Anne largely disappeared from the historical record thereafter.

Anne Bonney and Mary Read headline the golden age of piracy

“Had you fought like a man, you need not be hanged like a dog.” — Anne Bonny

It was not long after the turn of the 18th century that piracy in the Caribbean reached its peak, with the period from 1716 to 1726 considered the apex. as multiple colonial powers – Dutch, British, Spanish and French – jostled for position. But with resources also required for conflicts back in Europe, local representatives were largely reliant on their own recruitment efforts, and were typically none too fussy about where ships or sailors came from, or exactly how they operated. It was in this environment that two of the most famous female pirates of all time are found. While they were initially independent and separate, they ended their careers fighting alongside each other as part of the crew of another renowned name, John Rackham, a.k.a. Calico Jack.

It was not long after the turn of the 18th century that piracy in the Caribbean reached its peak, with the period from 1716 to 1726 considered the apex. as multiple colonial powers – Dutch, British, Spanish and French – jostled for position. But with resources also required for conflicts back in Europe, local representatives were largely reliant on their own recruitment efforts, and were typically none too fussy about where ships or sailors came from, or exactly how they operated. It was in this environment that two of the most famous female pirates of all time are found. While they were initially independent and separate, they ended their careers fighting alongside each other as part of the crew of another renowned name, John Rackham, a.k.a. Calico Jack.

Anne was the daughter of a Irish lawyer who emigrated to America when she was young. She reportedly demonstrated a fiery temper, stabbing a servant at age 13, then married minor pirate James Bonney, and moved with him to Nassau, a sanctuary for pirates supporting the English crown. There, she met Rackham, became his lover and eventually abandoned her husband – according to lore, disgusted by James having turned informant. She never saw the need to disguise her sex, but was apparently among the first to realize that new shipmate “Mark Read” was not exactly all he claimed to be. For Mark was actually Mary Read, though she had been brought up as a boy since she was very young, part of a plot to fleece money out of her grandfather. Read, however, continued the deception after leaving home, and served in the British military before eventually marrying another soldier. When he died, she set sail for the West Indies, but the ship was captured by pirates, and “Mark” was pressed into service, reverting to the illusion of manhood.

Some time later, she ended up becoming part of Calico Jack’s crew, and things became murky. Some say Bonney took a fancy to the young “man”, or that Jack grew jealous of their relationship, before matters were settled peacefully, and both allowed to remain part of the crew. This didn’t last long though: in October 1720, the ship of pirate hunter Jonathan Barnet attacked Rackham’s vessel. Whether through drink or cowardice, most pirates failed to put up a fight, leaving Bonney and Read to lead the defense. According to Daniel Defoe, the creator of Robinson Crusoe, who also wrote a book called The General History of the Pyrates, “none kept the Deck except Mary Read and Anne Bonny, and one more; upon which, she, Mary Read, called to those under Deck, to come up and fight like Men, and finding they did not stir, fired her Arms down the Hold amongst them, killing one, and wounding others.” However, they were overpowered and, along with Rackham, taken to Jamaica. There, they were tried, convicted and sentenced to death – leading to the quote above, reputedly Bonny’s last words to her man. The two women both claimed to be pregnant, allowing them a stay of execution. For Read, it was a temporary escape as she died of a fever in prison. Bonney? History has no record of either her execution or her release. Make up your own ending.

Ching Shih

But it’s the other side of the globe which saw perhaps the most successful female pirate of them all. Some estimates have her in command of up to 1,800 ships and 80,000 crew, her territory covering much of the China Sea in the early years of the 19th century. It’s one hell of a character arc. She was originally a prostitute in the City of Canton, but was captured by pirates, and married one, Zheng Yi, in 1801. He came from a long line of buccaneers, and forged a coalition of rivals into one entity, the Red Flag fleet. Zheng died in 1807, but his widow used her own phenomenal negotiating and political skills, not just to hold the fleet together, in the face of circling rivals seeking to take advantage, but to increase its strength even further. She bedded her husband’s adoptive nephew, Chang Pao – who, some say, was also his lover.

But it’s the other side of the globe which saw perhaps the most successful female pirate of them all. Some estimates have her in command of up to 1,800 ships and 80,000 crew, her territory covering much of the China Sea in the early years of the 19th century. It’s one hell of a character arc. She was originally a prostitute in the City of Canton, but was captured by pirates, and married one, Zheng Yi, in 1801. He came from a long line of buccaneers, and forged a coalition of rivals into one entity, the Red Flag fleet. Zheng died in 1807, but his widow used her own phenomenal negotiating and political skills, not just to hold the fleet together, in the face of circling rivals seeking to take advantage, but to increase its strength even further. She bedded her husband’s adoptive nephew, Chang Pao – who, some say, was also his lover.

She is particularly remember for a rigorous pirate code, which punished disobedience harshly, and helped forge a force which basically ruled the waves. The Chinese navy couldn’t defeat her. Even the colonial superpowers in the area, the British and Portuguese, were unable to restrain Ching’s fleet. In the end, the Chinese government basically said, “Look, just stop, and we’ll give you amnesty for everything you’ve done.” There was some friction over the authorities’ demand that the pirates kneel to them – something Ching Shih refused to do. But a compromise was reached whereby a government official would act as witness at her wedding to Chang Pao, so could be acknowledged without loss of face. She lived up to her end of the bargain, becoming one of the very few ever to retire from piracy with both life and loot intact. Ching opened a gambling house back in Canton, where she lived for more than three decades, before dying at the ripe old age for a pirate, of 69. Well played, madam.

Women pirates in the movies

There have been a number of attempts to depict women pirates over the years, in . Some are fully reviewed elsewhere on the site, as listed at the end. But there are others worth at least a mention in passing.

- The Spanish Main (1945) – Binnie Barnes takes on the role of Anne Bonny.

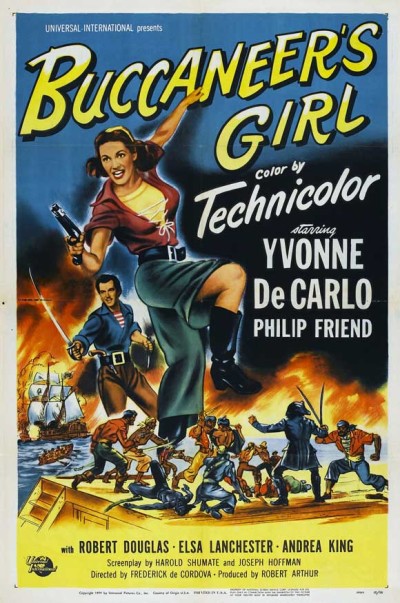

- Buccaneer’s Girl (1950) – Yvonne de Carlo stars as a New Orleans singer who becomes involved with a pirate.

- Against All Flags (1951) – Errol Flynn falls in love with pirate captain “Spitfire” Stevens (Maureen O’Hara), even as he is on an undercover mission to take down her organization.

- The Golden Hawk (1952) – French sea captain Kit Gerardo (Sterling Hayden) seeks the pirate responsible for killing his mother, and meets female buccaneer Captain Rouge (Rhonda Fleming).

- The King’s Pirate (1967) – A remake of Against All Flags, with Doug McClure and Jill St. John playing the two leads.

- Pirates of the Caribbean: At World’s End (2007) – Likely inspired by Ching Shih, the third entry included Mistress Ching (Takayo Fischer), a pirate queen who retired to enjoy her incredible wealth.

- Black Sails (2014) – Anne Bonny is portrayed in the Starz series by Clara Paget.

One worth mentioning never got off the ground. In the early 1990’s Paul Verhoeven was working on a film called Anne Bonny: Mistress of the Seas, based on John Carlova’s book. It had a stellar cast, with Geena Davis attached, plus Harrison Ford and Michelle Pfeiffer as Calico Jack and Mary Read. However, Pfeiffer soon lost interest, saying, “I had two meetings with Paul Verhoeven… Both conversations were about how much skin I would show.” She may have had a point, one studio exec describing Verhoven’s concept as ”a sex film that, oh, by the way, had a couple of ships in it.” Pressed to take it mainstream, the director left in July 1993, citing “creative differences”, and the studio turned to Davis’s beau Renny Harlin instead. However, Verhoeven agreed to return, only for Davis to bail, allegedly due to the studio ditching her man. She and Harlin went on to make Cutthroat Island, a megaflop which basically killed the entire pirate genre for a decade. Verhoeven was left without a star, and eventually, a film, sniping, “The studio didn’t dare to make a movie about a woman.”

There’s another project which was announced a year ago, but of which little has been heard since. In February 2014, news broke of a “limited series” biopic from Steven Jensen’s Independent Television Group, about Ching Shih called Red Flag, starring Nikita‘s Maggie Q as the Chinese pirate. Said Q, “It’s exciting to have the opportunity to share Ching Shih’s real-life story with audiences that are both familiar and unfamiliar with her prominent history.” But since then? Nothing since March, when it was announced that Francois Arnaud would be the male lead. The silence may not be terminal at this point, and the project is still listed as “in development” on IMDb, but I’d have though something further would have happened by now…

See also

- Anne of the Indies

- Le Avventure di Mary Read

- Cutthroat Island

- Cutthroat Island: 20 years on

- Grace O’Malley: Scourge of the Sea

- The Legendary Adventures of the Pirate Queens, by James Grant Goldin

- The Muthers

- The Pirate Vortex, by Deborah Cannon

- Pirates! by Celia Rees

- The Queen of the Pirates

- Tiger of the Seven Seas

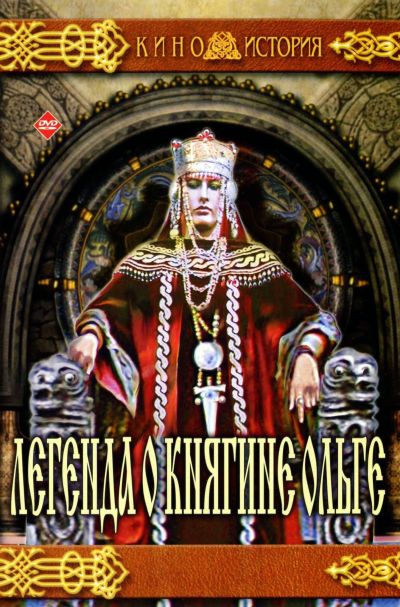

While the film itself is not that good, it did introduce me to a new action heroine of history: Olga of Kiev, who seems to have been a serious bad-ass, even by the high standards of European bad-asses of the time. There’s some suggestion she was of Viking extraction, with her name originally Helga, and that would certainly make sense. She married Igor of Kiev around 903, and after his death, ruled the state of Kievan Rus’ for 18 years, in the name of her young son, Svyatoslav. The Russian Primary Chronicle

While the film itself is not that good, it did introduce me to a new action heroine of history: Olga of Kiev, who seems to have been a serious bad-ass, even by the high standards of European bad-asses of the time. There’s some suggestion she was of Viking extraction, with her name originally Helga, and that would certainly make sense. She married Igor of Kiev around 903, and after his death, ruled the state of Kievan Rus’ for 18 years, in the name of her young son, Svyatoslav. The Russian Primary Chronicle  The key to the 2011 findings was the decision to determine the sex of buried Viking skeletons by analyzing the buried Viking skeletons. This may seem fairly basic to us laymen, but apparently, the previous technique involved deciding that if you were buried with a sword or shield. you were a man, and if you had a brooch, you were a woman. This led to the conclusion that Viking raiding parties were overwhelmingly male. However, a re-examination of 14 Norse burials, examining the bones rather than the contents alongside them, showed six were women, seven were men, and one was unable to be determined. This suggests,

The key to the 2011 findings was the decision to determine the sex of buried Viking skeletons by analyzing the buried Viking skeletons. This may seem fairly basic to us laymen, but apparently, the previous technique involved deciding that if you were buried with a sword or shield. you were a man, and if you had a brooch, you were a woman. This led to the conclusion that Viking raiding parties were overwhelmingly male. However, a re-examination of 14 Norse burials, examining the bones rather than the contents alongside them, showed six were women, seven were men, and one was unable to be determined. This suggests,

‘Ride of the Valkyries’ by John Charles Dollman [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

‘Ride of the Valkyries’ by John Charles Dollman [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

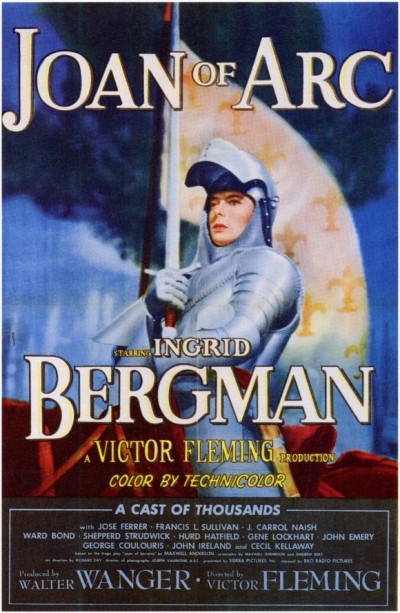

This film’s origins as a stage play are painfully apparent, and you can also see why the distributor’s felt it needed to have 45 minutes cut out before it could be released, as frankly, it’s a bit of a bore. The battle to recapture Orleans is the only action of note here, even though that represented the start of the Maid’s campaign to restore France to its proper ruler (Ferrer), rather than the end. After that, this more or less skips forward to his coronation, then Joan’s capture, spending the rest of the movie – and there’s a lot of it – going through the trial, and the railroading of the heroine into, first throwing herself on the church’s mercy, then recanting her recantation and returning to wearing men’s clothes, thereby sealing her fate. There’s not much here which you won’t have seen before, if you’ve seen any of the other versions of the story, touching the usual bases from Joan’s revelations that she’s going to be the saviour of France, through her trip to see the Dauphin, and so on. It does downplay the “voices” aspect, especially early on, perhaps a wise move since it’s difficult to depict, without making her seem like a religious fruitcake.

This film’s origins as a stage play are painfully apparent, and you can also see why the distributor’s felt it needed to have 45 minutes cut out before it could be released, as frankly, it’s a bit of a bore. The battle to recapture Orleans is the only action of note here, even though that represented the start of the Maid’s campaign to restore France to its proper ruler (Ferrer), rather than the end. After that, this more or less skips forward to his coronation, then Joan’s capture, spending the rest of the movie – and there’s a lot of it – going through the trial, and the railroading of the heroine into, first throwing herself on the church’s mercy, then recanting her recantation and returning to wearing men’s clothes, thereby sealing her fate. There’s not much here which you won’t have seen before, if you’ve seen any of the other versions of the story, touching the usual bases from Joan’s revelations that she’s going to be the saviour of France, through her trip to see the Dauphin, and so on. It does downplay the “voices” aspect, especially early on, perhaps a wise move since it’s difficult to depict, without making her seem like a religious fruitcake. In the late seventies, British television was notable for series which generally kicked ass on the performance front, but suffered from woefully inadequate production values. The most well-known example is Doctor Who, but that was just the tip of a dramatic iceberg which included the likes of Blake’s 7 and this series: in some cases, you can look past or ignore the deficiencies, because the acting is good enough to counteract them. That, sadly, isn’t the case here, with Phillips (a compatriot of Diana Rigg and Glenda Jackson at RADA) sadly adrift as Boudicca, the queen of the Iceni who takes on the occupying Roman forces after her daughters are assaulted. Having enjoyed the 2003 version, with Alex Kingston in the title role, I thought I’d give this one a chance, but when a supposed army of 6,000 is represented by four chariots and, maybe, ten guys in animal skins, it’s hard not to notice.

In the late seventies, British television was notable for series which generally kicked ass on the performance front, but suffered from woefully inadequate production values. The most well-known example is Doctor Who, but that was just the tip of a dramatic iceberg which included the likes of Blake’s 7 and this series: in some cases, you can look past or ignore the deficiencies, because the acting is good enough to counteract them. That, sadly, isn’t the case here, with Phillips (a compatriot of Diana Rigg and Glenda Jackson at RADA) sadly adrift as Boudicca, the queen of the Iceni who takes on the occupying Roman forces after her daughters are assaulted. Having enjoyed the 2003 version, with Alex Kingston in the title role, I thought I’d give this one a chance, but when a supposed army of 6,000 is represented by four chariots and, maybe, ten guys in animal skins, it’s hard not to notice. Probably best to approach this with few expectations of this being a factual representation of the time; more than once, it felt clearly like the writer was using the Roman occupation of Britain, and Boudica’s rebellion, as a metaphor for American’s involvement in Iraq. There are certainly enough anachronisms, particularly in the dialogue (the Roman Emperor chatting informally away with the leader of a British tribe, and references to “terrorists”), that it seems deliberate. The basic story is the one well-known of legend: after her husband’s death, and the raping of her daughters by the invading Romans, Boudica (Kingston) led her tribe in an initially successful revolt, only to be stopped when the full force of the Empire was turned on them.

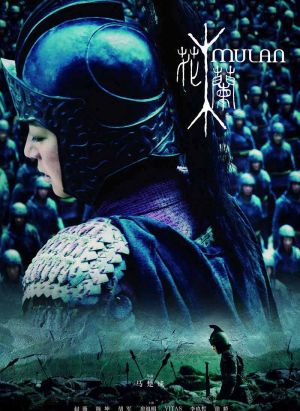

Probably best to approach this with few expectations of this being a factual representation of the time; more than once, it felt clearly like the writer was using the Roman occupation of Britain, and Boudica’s rebellion, as a metaphor for American’s involvement in Iraq. There are certainly enough anachronisms, particularly in the dialogue (the Roman Emperor chatting informally away with the leader of a British tribe, and references to “terrorists”), that it seems deliberate. The basic story is the one well-known of legend: after her husband’s death, and the raping of her daughters by the invading Romans, Boudica (Kingston) led her tribe in an initially successful revolt, only to be stopped when the full force of the Empire was turned on them. Inspired by the same poem as Disney’s much-loved feature, this has the same basic idea – a young woman impersonates a man in order to save her father from being drafted in the army. However, this takes a rather different approach, being much darker in tone, not that’s this is much of a surprise, I guess. It’s also a lot longer in scope, with Mulan (Zhao, whom you may recognize as the heroine/goalkeeper from Shaolin Soccer), rather than fighting a single campaign, becoming a career soldier and rising through the ranks as a result of her bravery in battle, eventually becoming a general, tasked with defending the Wei nation from the villainous Mendu (Hu). He has killed his own father in order to take control, and has united the nomadic tribes of the Rouran, amassing an army of 200,000 to invade Mulan’s home territory. She comes up with a plan to lure him into a trap, but when she is betrayed by a cowardly commander, things look bleak indeed for Mulan and Wentai (Chen), one of the few who know her secret.

Inspired by the same poem as Disney’s much-loved feature, this has the same basic idea – a young woman impersonates a man in order to save her father from being drafted in the army. However, this takes a rather different approach, being much darker in tone, not that’s this is much of a surprise, I guess. It’s also a lot longer in scope, with Mulan (Zhao, whom you may recognize as the heroine/goalkeeper from Shaolin Soccer), rather than fighting a single campaign, becoming a career soldier and rising through the ranks as a result of her bravery in battle, eventually becoming a general, tasked with defending the Wei nation from the villainous Mendu (Hu). He has killed his own father in order to take control, and has united the nomadic tribes of the Rouran, amassing an army of 200,000 to invade Mulan’s home territory. She comes up with a plan to lure him into a trap, but when she is betrayed by a cowardly commander, things look bleak indeed for Mulan and Wentai (Chen), one of the few who know her secret. I find the line between “terrorist” and “freedom fighter” an interesting one, drawn not so much by any objective measure, but by the viewer’s perspective and historical hindsight. Qiu Jin is a good example: she fought against the perceived oppression – particularly of women – by the Qing dynasty in the early 20th century, and ended up getting publicly beheaded for her support of revolutionary factions, by the government of the time. Now? A heroine and a martyr, who has an official museum ‘n’ stuff. Funny how things work out.

I find the line between “terrorist” and “freedom fighter” an interesting one, drawn not so much by any objective measure, but by the viewer’s perspective and historical hindsight. Qiu Jin is a good example: she fought against the perceived oppression – particularly of women – by the Qing dynasty in the early 20th century, and ended up getting publicly beheaded for her support of revolutionary factions, by the government of the time. Now? A heroine and a martyr, who has an official museum ‘n’ stuff. Funny how things work out.