★★★½

“We need to go deeper…”

Despite the critical and commercial success of the original film, it took a while for anything further to emerge from the GitS universe. Over the seven years after the movie, the only adapted media to be released was a 1997 video-game. This hiatus came to an end in October 2002 when Stand Alone Complex took the air on Japanese satellite station SKY PerfecTV!. This was a 26-part series, each episode lasting 25 minutes, and was followed in 2004 by S.A.C. 2nd GIG, which had the same format. In turn, the first season was adapted into both a feature-length version, The Laughing Man, and two manga volumes, while the second was also edited down into a feature-length edition, Individual Eleven.

Despite the critical and commercial success of the original film, it took a while for anything further to emerge from the GitS universe. Over the seven years after the movie, the only adapted media to be released was a 1997 video-game. This hiatus came to an end in October 2002 when Stand Alone Complex took the air on Japanese satellite station SKY PerfecTV!. This was a 26-part series, each episode lasting 25 minutes, and was followed in 2004 by S.A.C. 2nd GIG, which had the same format. In turn, the first season was adapted into both a feature-length version, The Laughing Man, and two manga volumes, while the second was also edited down into a feature-length edition, Individual Eleven.

The main advantage the TV series offers over the movie should be apparent: it has much greater scope at which to explore the world of cyberbrain networks, information warfare, and their resulting impact on society and humanity. This is particularly apparent early on in the first series. There does eventually develop an ongoing story arc, focusing on the search for an elite hacker (the “Laughing Man”, who takes inspiration from a J.D. Salinger short story) who is trying to expose a conspiracy between the government and cyber-medical companies. But the series also has episodes that don’t advance this at all, exploring other aspects of life in the technologically advanced society which is 2030’s Japan.

It can also be pretty damn cerebral at times. Even the titlular concept, the “Stand Alone Complex”, is not easy for the viewer to wrap their head around. It’s a little bit like the notion of copycat incidents – except, in the case of the Stand Alone Complex, the original didn’t take place, or at least not in the way perceived by those who copy it. It’s probably easiest to provide an example: “Slender Man”. This was a supposed supernatural creature, belief in which reportedly caused two 12-year-old girls to stab another, a ritual designed to impress Slender Man. But the urban legend in question was actually a piece of fiction, created wholesale by a Internet forum user. This idea informs both seasons, with reality and perceived reality both triggering subsequent actions. It’s sometimes way above my head, that’s for sure.

Another result of the extra room is an approach which occasionally becomes meandering to the point of irritation. On the other hand, you can only admire a show which is confident enough in its own abilities, to have an episode which takes place, almost in its entirety, in an Internet chat room. Another ongoing thread is the growing self-awareness of the Tachikomas, independent AI tanks employed by Section 9. These feature in little vignettes at the end of every episode in the first season. To be honest, I initially found their squeaky little voices fairly irritating and fast-forwarded as soon as the final credits rolled. However, they did redeem themselves with a surprising bit of altruism at the end of the series, and were considerably more tolerable in the second season.

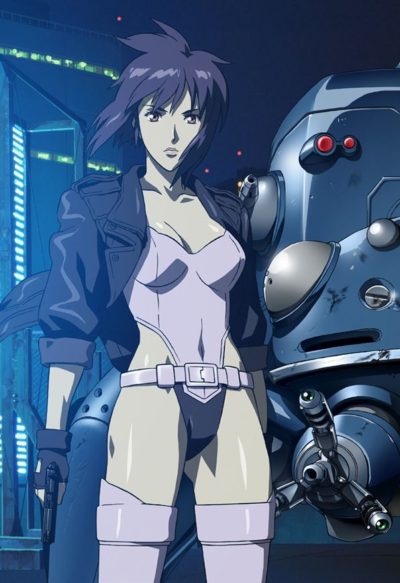

Compared to the movie, the animation is a little less fluid – as you’d expect, given the constraints of cost and time. The budget was reportedly $300,000 per episode, compared to $10 million for the film: so the entire first season, running nine hours or so (excluding credits), still cost less than the 80-minute movie, even allowing for seven years of inflation. The style is also a little different, with the character designs more closely resembling the original manga. This is perhaps most apparent in the look of Major Kusanagi. For the TV version seems quite enthusiastic in the area of fan service, with some of her costumes looking as if she’d just rolled out of a Victoria’s Secret catalogue, rather than those typically worn by a public servant – see below for an example!

While the feature focused directly on the Major and her quest for identity, the series also uses its greater freedom to become more of an ensemble piece. The Major is clearly still the leader and boss, with skills that surpass everyone else – they defer to her, and it’s entirely understandable. But over the course of these 52 episodes, the spotlight turns at one point onto just about everyone else, from her hulking second-in-command, former Army Ranger Batou, through to Togusa, the member of Section 9 who has undergone the least amount of cybernetic enhancement. This allows it to explore their history. For example, the (somewhat notorious, due to its graphic violence) “Jungle Cruise” episode, had Batou hunting down an ex-military colleague who has become a serial killer.

While the feature focused directly on the Major and her quest for identity, the series also uses its greater freedom to become more of an ensemble piece. The Major is clearly still the leader and boss, with skills that surpass everyone else – they defer to her, and it’s entirely understandable. But over the course of these 52 episodes, the spotlight turns at one point onto just about everyone else, from her hulking second-in-command, former Army Ranger Batou, through to Togusa, the member of Section 9 who has undergone the least amount of cybernetic enhancement. This allows it to explore their history. For example, the (somewhat notorious, due to its graphic violence) “Jungle Cruise” episode, had Batou hunting down an ex-military colleague who has become a serial killer.

The second season, while still having some individual episodes, has an interesting main thread which has become particularly relevant in the light of subsequent geo-political events. A refugee crisis has broken out, leading to a large influx of displaced people to Japan, causing tension between them and the locals. A charismatic refugee leader, Kuze, has sprung up, leading a movement demanding autonomy for the island where they are being housed. A right-wing group within the government, led by creepy intelligence officer Goda, seeks to exploit the tension by “false flagging” a nuclear incident as a refugee terrorist act, allowing the group to stage effectively a military coup. While originally inspired by the Japanese reaction to 9/11, it’s easy to see parallels to the current world situation here.

Partly due to this, I’m curious to see how much of the series ends up present in the live-action film. The very first episode includes a hostage situation involving android geisha, which is a part of the trailers we’ve seen. As mentioned, each series was edited down into a feature-length compilation, so could be the basis for the 2017 story – though as I haven’t bothered with those, I can’t comment on how coherent the results ended up. But other aspects of the trailers appear to come from the original movie, so I suspect we’ll be looking at a combination, drawing from multiple elements of the GitS universe. It’ll probably be based more on “what looks cool?” rather than narrative sense!

Dir: Kenji Kamiyama

Star (voice): Mary Elizabeth McGlynn, Richard Epcar, Crispin Freeman, William Frederick Knight

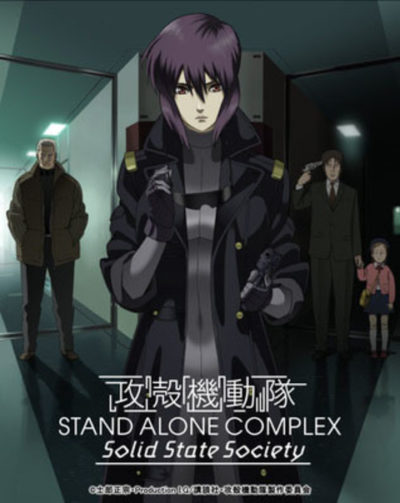

Ghost in the Shell: Stand Alone Complex – Solid State Society

★★½

“Solid State Survivors.”

A rather clunky title for an OAV (original animation video), which came out in September 2006, about 18 months after the end of season two. It’s also two years after the events depicted, with Major Kusanagi (Tanaka) having quit her job as Section 9, and largely dropped off the grid. Batou (Ōtsuka) has taken over her position as S9’s top field operative, with Togusa (Yamadera) the. After a series of suicides exposes a plot for a bioterror attack, the group is on the hunt for a hacker called the Puppeteer, apparently behind it. But the investigation finds the apparent attack was almost a diversion, and uncovers a massive child abduction ring that may be responsible for as many as 20,000 kidnappings.

A rather clunky title for an OAV (original animation video), which came out in September 2006, about 18 months after the end of season two. It’s also two years after the events depicted, with Major Kusanagi (Tanaka) having quit her job as Section 9, and largely dropped off the grid. Batou (Ōtsuka) has taken over her position as S9’s top field operative, with Togusa (Yamadera) the. After a series of suicides exposes a plot for a bioterror attack, the group is on the hunt for a hacker called the Puppeteer, apparently behind it. But the investigation finds the apparent attack was almost a diversion, and uncovers a massive child abduction ring that may be responsible for as many as 20,000 kidnappings.

Even by the standards of a series which has always waxed philosophical, this has some pretty deep constructs. For example, the Puppeteer is described by the Major as a “rhizome”. Wikipedia tells me this is a concept developed by Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari in their Capitalism and Schizophrenia (1972–1980) project. It is what Deleuze calls an “image of thought,” based on the botanical rhizome, that apprehends multiplicities. Well, glad we’ve cleared that up, then. Fortunately, you don’t really need to understand any of this: basically just think of of it as an example of a computer network becoming self-aware, and acting on its own behalf. Everything beyond that, feels a bit like extracts from a paper by a college student who wants you to know how deep they are.

It’s somewhat better when not vanishing up its own philosophical backside. Probably the best sequence has Togusa becoming the victim of a brain-hack and compelled to make a terrible choice: hand his own daughter over to the Puppeteer, to become one of the abductees (with his memory then wiped) or kill himself. It’s a chilling sequence, and also marks the return of the Major to work with Section 9. She has been carrying out her own investigation, free from the restrictions inevitably resulting out of her official role. It turns out to be connected to the aging of Japanese society – a major problem now, and likely to be worse by the late 2030’s when this is set.

It looks pretty slick, with a budget definitely on the high-end for video animation, and there’s no need to have seen the TV series, for this to make sense. But it’s largely forgettable stuff, and the significant absence of the Major, particularly in the first half, weakens proceedings considerably, robbing it of the universe’s most memorable character.

Dir: Kenji Kamiyama

Star (voice): Atsuko Tanaka, Akio Ōtsuka, Koichi Yamadera, Osamu Saka

You might be forgiven for expecting something Hunger Games-like, given Katniss was referred to frequently as the “girl on fire,” only one letter different from the title here. That really isn’t the case at all: though both are, broadly speaking, science-fiction, instead of an urban dystopia, this is sprawling space opera. The heroine, 17-year-old Trattora, lives on Cwelt, a fringe planet largely overlooked and bypassed by the rest of the galaxy. She’s a chieftain’s daughter there, but was adopted, and is clearly different from the rest of her people; she yearns to find the truth about her ancestry.

You might be forgiven for expecting something Hunger Games-like, given Katniss was referred to frequently as the “girl on fire,” only one letter different from the title here. That really isn’t the case at all: though both are, broadly speaking, science-fiction, instead of an urban dystopia, this is sprawling space opera. The heroine, 17-year-old Trattora, lives on Cwelt, a fringe planet largely overlooked and bypassed by the rest of the galaxy. She’s a chieftain’s daughter there, but was adopted, and is clearly different from the rest of her people; she yearns to find the truth about her ancestry.

It’s always interesting when reviews of a film are deeply polarized, and that’s the case here. The first page of Google results run the gamut from “I simply despised the film as a whole” to “The images are frightening within, and the only thing better than the scares are the performances.” While I lean toward the latter, I can see how this could have failed to make a connection with some viewers, and if that happens, then there isn’t much else to prevent the former opinion. It’s the kind of film where there isn’t likey to be a middle ground in reactions.

It’s always interesting when reviews of a film are deeply polarized, and that’s the case here. The first page of Google results run the gamut from “I simply despised the film as a whole” to “The images are frightening within, and the only thing better than the scares are the performances.” While I lean toward the latter, I can see how this could have failed to make a connection with some viewers, and if that happens, then there isn’t much else to prevent the former opinion. It’s the kind of film where there isn’t likey to be a middle ground in reactions. ★★★

★★★ The story has a very clever approach to the whole “whitewashing” controversy: at least initially, rather than Motoko Kusanagi, she has been reinvented by Hanka Robotics as Mira Killian, who give her a whole new set of memories, which may or may not be accurate. It’s this quest for her real identity which drives the plot, containing more than a few echoes of Robocop. And that’s an illustration of the main problem here: it feels less like anything cutting edge, than a conglomeration of elements taken from films which has gone before. That half of these stole from the animated Ghost, doesn’t help the live-action version much.

The story has a very clever approach to the whole “whitewashing” controversy: at least initially, rather than Motoko Kusanagi, she has been reinvented by Hanka Robotics as Mira Killian, who give her a whole new set of memories, which may or may not be accurate. It’s this quest for her real identity which drives the plot, containing more than a few echoes of Robocop. And that’s an illustration of the main problem here: it feels less like anything cutting edge, than a conglomeration of elements taken from films which has gone before. That half of these stole from the animated Ghost, doesn’t help the live-action version much.

★★★★

★★★★ Much more a reboot, complete with a redesigned lead, than any kind of sequel, this four-part series of hour-long episodes received a theatrical release in Japan, before being released on DVD. In a typically confusing GitS universe approach, it was then broadcast on TV in 10 episodes, with extra material added. I mention this only because it’s the four-part version which will be reviewed here. It starts before Major Kusanagi (Maxwell) joins up with her boss, Aramaki (Swasey): initially, she’s part of the 501st, a counter-cyberterrorism group which owns her cyborg body. However, Aramaki offers her the opportunity to go freelance under him, doing similar work, and assemble a team who will largely be free from bureaucratic oversight.

Much more a reboot, complete with a redesigned lead, than any kind of sequel, this four-part series of hour-long episodes received a theatrical release in Japan, before being released on DVD. In a typically confusing GitS universe approach, it was then broadcast on TV in 10 episodes, with extra material added. I mention this only because it’s the four-part version which will be reviewed here. It starts before Major Kusanagi (Maxwell) joins up with her boss, Aramaki (Swasey): initially, she’s part of the 501st, a counter-cyberterrorism group which owns her cyborg body. However, Aramaki offers her the opportunity to go freelance under him, doing similar work, and assemble a team who will largely be free from bureaucratic oversight. Over the course of the four episodes, she recruits others whose names will be familiar. For example, ex-Ranger Batou (Sabat), comes aboard after initially being part of a team working against Kusanagi, who are trying to prove government complicity in war crimes. This is an interesting change, compared to the previous versions, which always seemed to join Section 9 “in progress,” and provides some intriguing insight into what makes – literally, to some extent – the Major the way she is. For, in this incarnation, we discover that she has been in her prosthetic body since birth, and has never known any other way of life.

Over the course of the four episodes, she recruits others whose names will be familiar. For example, ex-Ranger Batou (Sabat), comes aboard after initially being part of a team working against Kusanagi, who are trying to prove government complicity in war crimes. This is an interesting change, compared to the previous versions, which always seemed to join Section 9 “in progress,” and provides some intriguing insight into what makes – literally, to some extent – the Major the way she is. For, in this incarnation, we discover that she has been in her prosthetic body since birth, and has never known any other way of life. This is largely included purely for completeness: if this had been a stand-alone film, it likely wouldn’t have qualified, not reaching the mandatory minimum quota of action heroineness. For in this sequel, Major Kusanagi (Tanaka) has abandoned even her artificial physical form, for life entirely inside the Internet. Her presence in this is therefore more spiritual, with Batou (Yamadera) referring to her as his “guardian angel”, and her impact is more felt than seen – particularly in its ramification for Batou, whose degree of cybernetic enhancement is not much lower than hers. She only returns to a tangible persona in the final scene, where Batou has to take on a near-endless stream of combat-reprogrammed sex robots. My, that’s a phrase I never thought I’d be writing…

This is largely included purely for completeness: if this had been a stand-alone film, it likely wouldn’t have qualified, not reaching the mandatory minimum quota of action heroineness. For in this sequel, Major Kusanagi (Tanaka) has abandoned even her artificial physical form, for life entirely inside the Internet. Her presence in this is therefore more spiritual, with Batou (Yamadera) referring to her as his “guardian angel”, and her impact is more felt than seen – particularly in its ramification for Batou, whose degree of cybernetic enhancement is not much lower than hers. She only returns to a tangible persona in the final scene, where Batou has to take on a near-endless stream of combat-reprogrammed sex robots. My, that’s a phrase I never thought I’d be writing… Despite the critical and commercial success of the original film, it took a while for anything further to emerge from the GitS universe. Over the seven years after the movie, the only adapted media to be released was a 1997 video-game. This hiatus came to an end in October 2002 when Stand Alone Complex took the air on Japanese satellite station SKY PerfecTV!. This was a 26-part series, each episode lasting 25 minutes, and was followed in 2004 by S.A.C. 2nd GIG, which had the same format. In turn, the first season was adapted into both a feature-length version, The Laughing Man, and two manga volumes, while the second was also edited down into a feature-length edition, Individual Eleven.

Despite the critical and commercial success of the original film, it took a while for anything further to emerge from the GitS universe. Over the seven years after the movie, the only adapted media to be released was a 1997 video-game. This hiatus came to an end in October 2002 when Stand Alone Complex took the air on Japanese satellite station SKY PerfecTV!. This was a 26-part series, each episode lasting 25 minutes, and was followed in 2004 by S.A.C. 2nd GIG, which had the same format. In turn, the first season was adapted into both a feature-length version, The Laughing Man, and two manga volumes, while the second was also edited down into a feature-length edition, Individual Eleven. While the feature focused directly on the Major and her quest for identity, the series also uses its greater freedom to become more of an ensemble piece. The Major is clearly still the leader and boss, with skills that surpass everyone else – they defer to her, and it’s entirely understandable. But over the course of these 52 episodes, the spotlight turns at one point onto just about everyone else, from her hulking second-in-command, former Army Ranger Batou, through to Togusa, the member of Section 9 who has undergone the least amount of cybernetic enhancement. This allows it to explore their history. For example, the (somewhat notorious, due to its graphic violence) “Jungle Cruise” episode, had Batou hunting down an ex-military colleague who has become a serial killer.

While the feature focused directly on the Major and her quest for identity, the series also uses its greater freedom to become more of an ensemble piece. The Major is clearly still the leader and boss, with skills that surpass everyone else – they defer to her, and it’s entirely understandable. But over the course of these 52 episodes, the spotlight turns at one point onto just about everyone else, from her hulking second-in-command, former Army Ranger Batou, through to Togusa, the member of Section 9 who has undergone the least amount of cybernetic enhancement. This allows it to explore their history. For example, the (somewhat notorious, due to its graphic violence) “Jungle Cruise” episode, had Batou hunting down an ex-military colleague who has become a serial killer. A rather clunky title for an OAV (original animation video), which came out in September 2006, about 18 months after the end of season two. It’s also two years after the events depicted, with Major Kusanagi (Tanaka) having quit her job as Section 9, and largely dropped off the grid. Batou (Ōtsuka) has taken over her position as S9’s top field operative, with Togusa (Yamadera) the. After a series of suicides exposes a plot for a bioterror attack, the group is on the hunt for a hacker called the Puppeteer, apparently behind it. But the investigation finds the apparent attack was almost a diversion, and uncovers a massive child abduction ring that may be responsible for as many as 20,000 kidnappings.

A rather clunky title for an OAV (original animation video), which came out in September 2006, about 18 months after the end of season two. It’s also two years after the events depicted, with Major Kusanagi (Tanaka) having quit her job as Section 9, and largely dropped off the grid. Batou (Ōtsuka) has taken over her position as S9’s top field operative, with Togusa (Yamadera) the. After a series of suicides exposes a plot for a bioterror attack, the group is on the hunt for a hacker called the Puppeteer, apparently behind it. But the investigation finds the apparent attack was almost a diversion, and uncovers a massive child abduction ring that may be responsible for as many as 20,000 kidnappings. Renowned for its influence on just about every subsequent cyberpunk entity, from The Matrix to Westworld, this also remains one of the classic anime movies, more than two decades after its release. The main problem though, is the translation of a densely-packed and heavily notated manga series by Masamune Shirow, into an 82-minute action feature. You’re left with something forced to cram the philosophical aspects into a couple of indigestible lumps – an approach certainly also adopted by the Wachowski Brothers.

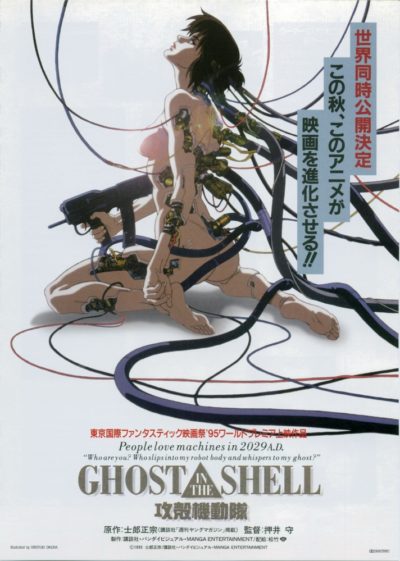

Renowned for its influence on just about every subsequent cyberpunk entity, from The Matrix to Westworld, this also remains one of the classic anime movies, more than two decades after its release. The main problem though, is the translation of a densely-packed and heavily notated manga series by Masamune Shirow, into an 82-minute action feature. You’re left with something forced to cram the philosophical aspects into a couple of indigestible lumps – an approach certainly also adopted by the Wachowski Brothers. I initially thought I had a fairly good handle on where the first book in the Immortal Vegas series (currently at six entries, plus a prequel) was going, with a Lara Croft-esque lead, who specializes in locating and recovering ancient artifacts. You can also throw in fragments of The Da Vinci Code, since she is hired to retrieve a relic from the secret basement beneath the Vatican, and is going up against a cult of religious, Catholic fanatics. But it somehow ends up taking a sharp right-turn, ending up in a version of Las Vegas where, just out of phase with the casinos and hotels, lurks a hidden dimension of other venues, populated by…

I initially thought I had a fairly good handle on where the first book in the Immortal Vegas series (currently at six entries, plus a prequel) was going, with a Lara Croft-esque lead, who specializes in locating and recovering ancient artifacts. You can also throw in fragments of The Da Vinci Code, since she is hired to retrieve a relic from the secret basement beneath the Vatican, and is going up against a cult of religious, Catholic fanatics. But it somehow ends up taking a sharp right-turn, ending up in a version of Las Vegas where, just out of phase with the casinos and hotels, lurks a hidden dimension of other venues, populated by… If this seems somewhat familiar, it’s because it is not dissimilar to

If this seems somewhat familiar, it’s because it is not dissimilar to