Literary rating: ★★★★½

Kick-butt quotient: ☆

This opening installment of the author’s Lockwood and Company series is a brisk-paced tale with easily flowing prose that would be a quick read for most folks. It’s a novel that will appeal to fans of the supernatural, as well as of feisty heroines.

This opening installment of the author’s Lockwood and Company series is a brisk-paced tale with easily flowing prose that would be a quick read for most folks. It’s a novel that will appeal to fans of the supernatural, as well as of feisty heroines.

Technically, this could be called fantasy, since it’s set in an alternate England. Aside from the Problem and its ramifications, the setting is much like the real world. (I originally thought it might be supposed to be our world, decades into the future, but a reference to capital punishment existing in England at the time of a 50-year-old murder precluded that idea.) But the ramifications of the Problem are big. For half a century, ghostly apparitions have become VERY common in England (it’s not said whether that’s true in the rest of the world), and universally recognized as real.

The ghostly Visitors aren’t always malevolent; but they can be, and their touch can kill. Curfews keep people indoors at night, iron and other charms are commonly used to ward buildings and people, and agencies that deal with apparitions are respected and profitable. But though most agencies are run and supervised by adults, only some children gifted with the sensitivity can see, hear or sense ghosts directly; and they lose this sensitivity as they become adults. So the field operatives of these agencies are tweens and teens; well-paid for their work, but subject to lethal danger all the same. Lockwood and Co. is atypical in not having adult supervisors; the teen owner and his two associates (one of whom is our narrator, Lucy Carlyle) are on their own.

This brings us to one point that’s admittedly unrealistic. I don’t mean the idea that society would countenance putting minors in harm’s way. If that’s what it took to handle something like the Problem, politicians and pundits who now wax eloquent about protecting children and the merits of child labor laws would hesitate about one nanosecond (if that). But it’s not likely that they’d tolerate three teens living together on their own and running their own business. True, Lockwood’s an orphan. But he’d been “in care” at one time, and I can’t see them voluntarily letting him out of it. Lucy’s a runaway, though not without some reason; and the fact that her Talent made her the main breadwinner for her mother and sister would give the former a big incentive to want her back. (Her cavalier abandonment of her family is the one blot on her character for me; I can see leaving, but not just abandoning without a goodbye or any further thought or contact.) We don’t know where George’s parents are; they’re not even mentioned.

This is Stroud’s way of freeing his teen characters to act on their own without adult guidance, and let his teen readers vicariously fantasize about being free to have their own adventures and show the mettle they think ((sometimes with a basis!) that they have, even if adults don’t agree. It’s certainly a conceptual flaw in the premise, though. (Like Ilona Andrews in her Kate Daniels series, he also doesn’t deal with the massive revolutionary social and ideological implications that a cultural admission that the supernatural is real would have.) But I still found this a great read!

With its teen characters, this is marketed as a YA novel. In keeping with that, it has no sex, hardly any bad language, and no wallowing in ultra-grisly or gross violence (though the feeling of danger is very real). But it’s not in any sense a dumbed-down or pablum read; it’s a quality work, which can easily command the appreciation of adult readers. Stroud delivers a well-constructed plot, excellently drawn main characters whom you readily like (with the single caveat above) and root for, and a style that’s about as pitch-perfect as one could ask for. The tone is mostly serious, and the author is one of the best I’ve read at evoking a menacing Gothic atmosphere in the right places. (If you’re a buff of haunted house yarns, you owe it to yourself to “visit” Combe Carey Hall –vicariously, with the light on.)

But he also knows when to insert a light leavening of humor, and the interactions of his three teens are as real-seeming as they come. Lucy has a great narrative voice. I classified her as an action heroine based on how she handles herself here in life-threatening physical challenges that demand guts, speed, and agility, although the foes she’s combatting aren’t flesh-and-blood humans. Intensely romance-allergic readers can take note that there’s none of THAT here –though I could imagine Lucy and Lockwood as a couple in a few years. And Lockwood’s a smart, resourceful, capable hero, in the psychic detective mold.

Bottom line: this is good, clean supernatural fiction, as it’s meant to be! I think most readers of that genre will eat it up with a spoon.

Author: Jonathan Stroud

Publisher: Doubleday, available through Amazon, both for Kindle and as a printed book.

A version of this review previously appeared on Goodreads.

This series opener is one that was been on my radar for a long time, so I was delighted to finally read it last year! Although I’m a science fiction fan, I’m not generally attracted to military SF, which of course this is. But that’s mostly because my impression is that much of that sub-genre concentrates heavily on futuristic military hardware, to the neglect of the human element (and I think the human element is what good literature is all about). But that’s not a problem here. To be sure, there’s futuristic military hardware, and techno-babble (see below). But the human element, and a rousing tale of human adventure, is the core of the book.

This series opener is one that was been on my radar for a long time, so I was delighted to finally read it last year! Although I’m a science fiction fan, I’m not generally attracted to military SF, which of course this is. But that’s mostly because my impression is that much of that sub-genre concentrates heavily on futuristic military hardware, to the neglect of the human element (and I think the human element is what good literature is all about). But that’s not a problem here. To be sure, there’s futuristic military hardware, and techno-babble (see below). But the human element, and a rousing tale of human adventure, is the core of the book. “Ilona Andrews” is the pen name of a husband-and-wife author team; her first name really is Ilona. (There’s some confusion about his; “About the Authors” in the edition I read gives it as Andrew, but a comment in the extra material uses Gordon, as does the author page on Goodreads. Possibly Andrew Gordon?) They’ve attained considerable success with their urban fantasy Kate Daniels series. Since I’m a fan of both supernatural fiction and strong, kick-butt heroines, it isn’t surprising that the series had been on my radar for a long time before I read this opening volume, as a buddy read with a friend. It didn’t disappoint!

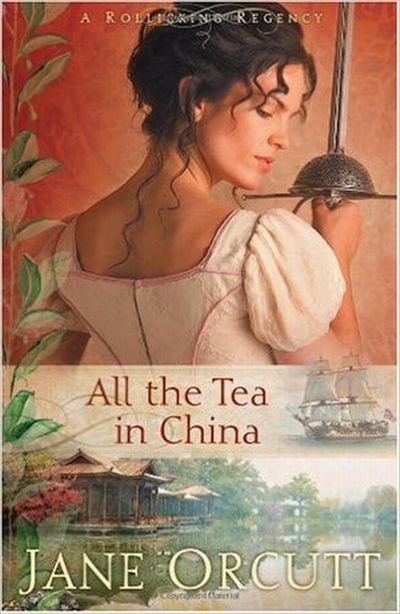

“Ilona Andrews” is the pen name of a husband-and-wife author team; her first name really is Ilona. (There’s some confusion about his; “About the Authors” in the edition I read gives it as Andrew, but a comment in the extra material uses Gordon, as does the author page on Goodreads. Possibly Andrew Gordon?) They’ve attained considerable success with their urban fantasy Kate Daniels series. Since I’m a fan of both supernatural fiction and strong, kick-butt heroines, it isn’t surprising that the series had been on my radar for a long time before I read this opening volume, as a buddy read with a friend. It didn’t disappoint! When I saw this book at a yard sale a few years ago, the captivating picture of a sword-wielding lady on the cover, coupled with the knowledge that the book is a romance by an evangelical Christian author, convinced me that this read would be right up my wife’s alley. I wasn’t wrong; she was initially skeptical of the historical setting (being more into modern settings), but once she got into it, she “couldn’t put it down.” She in turn recommended it to me; and obviously my reaction was positive as well!

When I saw this book at a yard sale a few years ago, the captivating picture of a sword-wielding lady on the cover, coupled with the knowledge that the book is a romance by an evangelical Christian author, convinced me that this read would be right up my wife’s alley. I wasn’t wrong; she was initially skeptical of the historical setting (being more into modern settings), but once she got into it, she “couldn’t put it down.” She in turn recommended it to me; and obviously my reaction was positive as well!