Literary rating: ★★★★

Kick-butt quotient: ☆☆

Born in 1875, as a youth Burroughs actually spent time working as a cowboy on a 19th-century Western ranch owned by his brother. Though that was in Idaho, while this novel is set in Arizona, his knowledge of basic ranch life and Western conditions in the frontier era was firsthand; and the descriptions here suggest that he had some personal familiarity with the landscape of the Southwest as well. So in this novel, he was following the axiomatic advice for authors, “Write about what you know.” His main weakness in much of his work, his disdain for research, is therefore largely moot here, while his main strengths –an ability to deliver adventurous plots and stirring depictions of action, creation of strong heroes who embody what are traditionally thought of as “masculine” virtues, moral clarity, and a masterful evocation of the theme of “primitivism” that can appeal to repressed and regimented readers– are undiminished. I’m not typically a Western fan, because I think modern examples of the genre too often degenerate into cliché.’ But the early Westerns produced by the writers of Burrough’s generation (which also included Zane Grey, whose influence I recognize here) preceded the modern cliches,’ and possess a more original quality –even if some of the tropes were beaten to death by later writers.

Born in 1875, as a youth Burroughs actually spent time working as a cowboy on a 19th-century Western ranch owned by his brother. Though that was in Idaho, while this novel is set in Arizona, his knowledge of basic ranch life and Western conditions in the frontier era was firsthand; and the descriptions here suggest that he had some personal familiarity with the landscape of the Southwest as well. So in this novel, he was following the axiomatic advice for authors, “Write about what you know.” His main weakness in much of his work, his disdain for research, is therefore largely moot here, while his main strengths –an ability to deliver adventurous plots and stirring depictions of action, creation of strong heroes who embody what are traditionally thought of as “masculine” virtues, moral clarity, and a masterful evocation of the theme of “primitivism” that can appeal to repressed and regimented readers– are undiminished. I’m not typically a Western fan, because I think modern examples of the genre too often degenerate into cliché.’ But the early Westerns produced by the writers of Burrough’s generation (which also included Zane Grey, whose influence I recognize here) preceded the modern cliches,’ and possess a more original quality –even if some of the tropes were beaten to death by later writers.

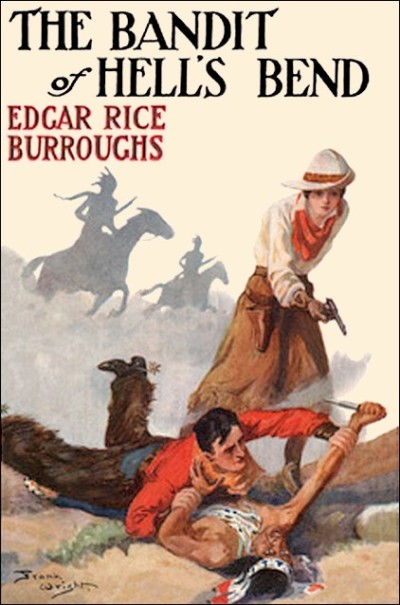

In 1880s Arizona, the inhabitants of the Bar-Y Ranch and neighboring Hendersville have to contend with occasional lethal Apache attacks, and the stage carrying bullion from Elias Henders’ mine is being held up with disconcerting regularity. Local suspicion pegs the principal masked culprit as Bar-Y cowboy Bull –but is local suspicion correct? And the plot will soon thicken, because both ranch and mine will face a suave menace that fights with the machinery of the law rather than with guns and tomahawks. The storyline is genuinely exciting, with a strong narrative drive that kept me eagerly turning pages to see what would happen next, with an element of mystery. (I guessed the culprit’s identity before the denouement, but I didn’t foresee everything that would happen.) Burroughs also understood that romance doesn’t need to be sappy to be romantic. There’s a well-drawn theme of conflict here between the effete, over-civilized, arrogant East that fights through dishonesty and wants to take from others (and the West that Burroughs saw was in many ways an oppressed colony of the U.S.-European industrialized world, as much as the hapless peoples of Asia and Africa were) vs. the primal, strong, down-to-earth West whose people look you in the eye and fight for what’s theirs

Burroughs has created a hero and heroine that you strongly care about, and want to see come through their jeopardy. Bull is more flawed than some Burrough’s heroes, because he has to struggle with a bit of an alcohol addiction; but that doesn’t diminish him for me –he’s a human being, with some human weakness as well as strength. Diana Henders is not a weak hot-house flower who functions solely as a damsel in distress –like any of us, she may find herself in need of a rescue sometime, but not through any weakness or incompetence on her part; and she’s also ready to do some rescuing herself when it’s needed. Of any of the Burroughs heroines I’ve encountered –and that’s been several– she’s the one I like the best, and that I find to be the most sharply-drawn, and most possessed of leadership and heroic qualities. (She’s an intelligent, likeable girl who enjoys reading and playing her piano. If you’re attacked by an Apache war party bent on ending your life, you’d also find her a very capable and cool-headed ally to have at your side with her Colt.) Some of the secondary characters here also come across as more vivid and lifelike than is usual for this writer, IMO.

Like other regional writers of his day, Burroughs was careful to reproduce authentic dialect in the character’s speech, indicated by unconventional spellings that reflect the pronunciations, not only of Western cowboy patois, but of a thick Irish brogue and a Chinese accent as well. This isn’t done to ridicule anyone; indeed, some characters who exhibit each of these speech patterns prove to be very sympathetic.

There’s a bit of ethnic stereotyping, in that Wong the cook is knowledgeable about poisons, and an opium user (of course, a fair number of 19th-century Chinese were opium users –not very surprisingly, since the British promoted the opium trade, and forced it on China in two wars!) and there’s no real attempt to understand or present the Apache viewpoint. (Though even if their basic grievances are just and legitimate, when they’re attacking with the intention of killing you, fighting back IS your only short-range option.) But the only real villains here are white. And while Bull’s comment, “Thet greaser’s whiter’n some white men,” is phrased in racist terms, the insight he’s experiencing is subversive of racism. (“Greaser” is an ethnic slur some characters use for the Hispanic character, but he thinks of Anglos as “gringos” with just as little authorial censure; I think Burroughs here is only reflecting the common parlance of the day, as with his dialect speech. When Wong is referred to as an “insolent Chink,” it’s by a creep whom the reader readily recognizes as Wong’s inferior.)

My rating of four stars rather than five was for a very few logical slips in details, and for a few glossed-over points where plot developments were a tad dubious, IMO. But those are quibbles; this was a really good read, for any Western and/or action adventure fan!

Author: Edgar Rice Burroughs

Publisher: Both Ace Books and CreateSpace, available through Amazon, both for Kindle and as a printed book.

A version of this review previously appeared on Goodreads.