Month: February 2018

The first action heroines

“Within a sensational action-adventure framework of the sort generally associated with male heroics, serials gave narrative preeminence to an intrepid young heroine who exhibited a variety of traditionally “masculine” qualities: physical strength and endurance, self-reliance, courage, social authority and freedom to explore novel experiences outside the domestic sphere.”

— Melodrama and Modernity: Early Sensational Cinema and Its Contexts by Ben Singer

Despite what some people apparently think, the action heroine predates Ellen Ripley by… oh, almost eight decades. What should likely be regarded as the first of its kind actually appeared just five years after the Lumiere brothers shocked the audiences with a train arriving at a station. It was called Le Duel d’Hamlet and was released in 1900, as part of a program at the Exposition Universelle in Paris that year. The film clocks in at just under two minutes, and is an excerpt from Shakespeare’s Hamlet, in particular the fencing scene with Laertes – it’s basically nothing but action! This is notable, not just for being the first filmed “version” of the play, but because the part of Hamlet is played by Sarah Bernhardt, at the time one of the most renowned stage actresses in France (or any other country).

Despite what some people apparently think, the action heroine predates Ellen Ripley by… oh, almost eight decades. What should likely be regarded as the first of its kind actually appeared just five years after the Lumiere brothers shocked the audiences with a train arriving at a station. It was called Le Duel d’Hamlet and was released in 1900, as part of a program at the Exposition Universelle in Paris that year. The film clocks in at just under two minutes, and is an excerpt from Shakespeare’s Hamlet, in particular the fencing scene with Laertes – it’s basically nothing but action! This is notable, not just for being the first filmed “version” of the play, but because the part of Hamlet is played by Sarah Bernhardt, at the time one of the most renowned stage actresses in France (or any other country).

However, the crown of the earliest “true” film action queen perhaps belongs to the little-known Gene Gauntier. She got her start in the first decade of the 20th century, before credits became established, which partly explains why her place in history has almost evaporated. She literally walked on to her first film set with no experience to become a stunt-woman, being thrown into 30-foot deep water – despite not being able to swim! While acting was not her sole talent – she wrote the scenario for a 1907 adaptation of Ben Hur, which ended up costing her studio $25,000 in a landmark copyright case – it was her role of “Nan, the Confederate Spy” which merits her claim to the title here. In 1909-10, the character appeared in The Girl Spy, The Girl Spy Before Vicksburg and The Further Adventures of the Girl Spy.

Similarly ground-breaking was What Happened to Mary – note, no question-mark, it being a statement rather than a question. This was the earliest motion picture serial made in the United States, the first of its 12 monthly episodes being released in July 1912. This was also a very early example of cross-promotion. The idea originated as, and was then tied to, a series of stories in Ladies’ World Magazine; these were left unfinished, as a contest for readers to submit their own endings. However, each episode stood alone, with titles such as The Escape from Bondage or A Race to New York.

The series helped make a star of Mary Fuller, who had previously appeared in 1910’s Frankenstein, the first cinematic adaptation of Mary Shelley’s story, playing the doctor’s fiancée. After Mary, she’d go on to further serial success with Dolly of the Dailies, which depicted the adventures of Dolly Desmond, lady reporter extraordinaire. In an October 1914 poll of stars in Motion Picture Magazine which garnered a total of 11 million votes, she finished third among actresses, behind only Clara Young and Mary Pickford. She was also a screenwriter, who had eight scripts turned into films between 1913 and 1915. But her career was basically over by 1917; she subsequently had more than one nervous breakdown and spent the last 26 years of her life in a psychiatric institution, before dying in 1973, all but forgotten.

Sadly, both these are now largely lost. Only a couple of episodes of Dolly survive, one discovered in New Zealand of all places (apparently, it was often the final worldwide stop for prints during the silent era) in 2010. That entry was #5, titled The Chinese Fan. In in, Dolly goes to Chinatown to review a play. Unfortunately, the brooch she is sporting is actually a Triad symbol, leading to her being kidnapped by a Chinese gang. However, this ordeal simply allows our heroine to help free a heiress, also abducted for the usual nefarious purposes of Chinese gangs from the era, fortuitously getting a scoop for her paper at the same time.

The popularity of Mary and Dolly led to a legion of imitators, including The Adventures of Kathlyn, which introduced the “cliff-hanger” concept to serials. It starred Kathlyn Williams, who like Fuller was a writer, and also directed on occasion. Kathlyn was a 13-episode series, which takes place in the Indian sub-continent, in the fictitious country of Allaha, as the heroine goes to rescue her kidnapped father from Oriental intrigue. While little remains of the series, or the feature version two years later, the novelization by Harold MacGrath is available through Project Gutenberg, and we have reviewed it here.

You will see her bound by fanatical natives on the top of a giant funeral pyre and watch the flames creeping ever nearer her helpless form. You will see her tied with thongs in a tiger trap as human bait for the blood thirsty beasts of the jungle. You will see her swimming for her life to escape a maddened water-buffalo in the black waters of a Bengal river. Time after time, in scene after scene, this actress takes her life in her hands and walks grimly up to the very jaws of death in order to portray with lifelike realism the actual adventures of MacGrath’s heroine.

— Advertising poster for The Adventures of Kathlyn

The series was ground-breaking in other ways, particularly its advertising. The film is credited by some as being the first use of a trailer: a short clip from the next episode shown at the end, to whet the audience’s appetite. Spin-off merchandising associated with it included a cocktail, face-power, perfume and more than one song. And like Mary, it was among the first examples of media cross-promotion, with the story being serialized in newspapers from Los Angeles to Boston. In Chicago, Kathlyn and Dolly ended up facing off directly. The former had her story serialized in the Chicago Tribune, the newspaper paying the then remarkable price of $12,000 for the rights – 10% of the cost of making the series, and about $300,000 in modern money. Following its success in boosting the publication’s circulation, its local rival the Evening American, under legendary mogul William Randolph Hearst, bought the rights to Dolly of the Dailies, in order to run its story there.

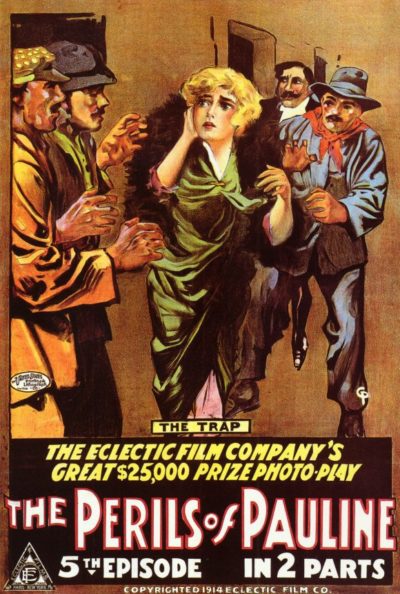

1914 saw action heroines become a veritable craze, giving us The Exploits of Elaine and The Perils of Pauline (both starring Pearl White), Lucille Love, Girl of Mystery (starring Grace Cunard) and The Hazards of Helen. White was perhaps the name most associated with serials in the public’s eye, appearing in half a dozen over the rest of the decade. [Though she was firmly based on the East coast, and apparently never even visited Hollywood] But Pauline remains perhaps the best known serial, with its simple yet open-ended plot. If Pauline Marvin (White) dies before she marries, she will not inherit her fortune; instead, it’ll go to her guardian, Koerner (Paul Panzer). No prizes for guessing where this leads. Repeatedly…

Grace Cunard was a particularly interesting character, who was a prolific writer, and co-directed many of her own adventures, alongside frequent co-star Francis Ford (the older brother of renowned Western director, John). Cunard created the character of “My Lady Raffles,” described as, “a jewel thief with a delightfully reckless charm,” and also played the Queen of the Apaches, a Robin Hood-like heroine, in the 1916 serial, The Purple Mask. The advertising for the latter series promised: “The most mysterious plot; the swiftest action; the most fascinating locale – Parisian high society and the Apache underworld; dare-devil stunts; romance, adventure – a true love-story”

“Miss Holmes is everywhere in the picture, flipping cars on fast moving trains, boarding engines and remaking train schedules after cutting into the train dispatcher’s wire from all sorts of remote mountain way stations; fording rivers up to her neck in icy water, and holding up members of the raiding gang at the point of her trusty automatic.”

— Reel Life, May 05, 1917

However, it was The Hazards of Helen which became the longest-running of these serials, with 119 episodes through February 1917. The first fifty or so episodes of Helen starred Helen Holmes, but when she left the studio, they turned to the woman generally recognized as Hollywood’s first stuntwoman, Rose Gibson (renaming her Helen Gibson, naturally!), who had occasionally doubled for Holmes. Gibson had first performed in a Wild West Show at age 17, but when her current employer suddenly closed, stranding the performers in California, she ended up working part-time in the fledgling movie industry. Her first billed role was in Ranch Girls on a Rampage, which is not as good as its title sounds.

Helen recounts the adventures of its titular heroine, a telegraph operator stationed at a remote outpost in the West, who saves the company from ruin and disaster on a near-weekly basis. There may have been some inspiration from Holmes herself, who was the daughter of a railroad engineer, and she also took a significant part in production behind the scenes. In a 1916 interview for The Green Book Magazine, she said, “If a photoplay actress wants to achieve real thrills, she must write them into the scenario herself. And the reason is odd: Nearly all scenario writers and authors for the films are men, and men usually won’t provide for a girl, things they wouldn’t do themselves. So if I want real thrilly action, I ask permission to write it in myself.”

Worth noting these early action heroine were not strictly limited to serials, however. The year also gave us the standalone short feature (1000 ft, which I think works out to about 14 minutes) When The Cartridges Failed. In this, Gertrude McCoy plays an office worker who stands in for the usual armed guard on a wage delivery. She has to defend the money from an attempted robbery, despite the revolver she was given having only two bullets loaded into it. While the movie itself is gone, the one still image which survives (above), suggests this may well be an early, standalone “girls with guns” film.

“I have always been afraid. But I would be ashamed to let fear rule me.” – Pearl White

These women didn’t just play daring heroines. Being an actor was a risky job in the early days, because it was a time before stands-in were at all common. If something dangerous needed to be done, it was usually the player who did it, and there was no respecting the gentler sex, when it came to embracing danger. For instance, in her diary entry for April 6th, 1914, Mary Fuller wrote, “They blew me up with a Black Hand bomb today, doing Dolly of the Dailies (No. 7). The charge of dynamite was very heavy. The shack was wrecked, my clothes were torn and blackened, and blood ran from a scalp wound,” adding almost laconically, “It was exciting. I hope my fans will like it.” She also almost drowned, filming a scene for Mary in which she played a mermaid.

Similarly, the Des Moines News in 1912 said admiringly of Kathlyn Williams, “She has never refused to risk her own safety for the sake of a good picture.” Her area of particular renown was working with animals, including big cats (as shown in the picture above), causing Kathlyn to be known as “the Unafraid”. Even before her serial, she required stitches in a head wound after a lion tore a gash in her scalp during the filming of Lost in the Jungle. The Los Angeles Times said of another Williams’ film, The Lady and the Tigers, “Miss Williams was required to enter the cage of three tigers lately brought from the jungle, which were untamed and didn’t know a moving-picture genius from a meat-pie.”

Injuries were common, though in the experience of Pearl White, they “never happened when I was doing what looked really dangerous… Why worry about the big things? It’s the little ones that get me.” But there was no shortage of major stunts done by these leading ladies. As an example, those performed by Helen Holmes included “riding a balky horse down a steep cliff and plunging into the river; dropping from an aerial steel cable onto the roof of a boxcar going 20 mph; leaping from a burning building; jumping from the roof of one moving train to another; and dropping from a trestle into an automobile.”

For real sangfroid though, it’s hard to beat Ruth Roland, star of 1919 series The Adventures of Ruth. According to her director there, George Marshall, “I used to shoot at her feet with real bullets. Didn’t bother her none.”

But it couldn’t last. From a modern perspective, the passing of the 19th amendment by Congress in 1919, giving women the right to vote, may have sapped the public’s drive for strong cinematic heroines. But for whatever reason, the genre died out almost entirely in the twenties. By 1936, the Los Angeles Times was able to proclaim, “There are no more serial queens…Helen Holmes, Pearl White and the others have long since retired, and the ladies of the serials now prefer to let their menfolk wear the pants.” It would be several more decades before anyone even remotely comparable would return to the screens in America.

Below, you’ll find a YouTube playlist including a number of the films discussed above, in chronological order. It starts with Sarah Bernhardt’s scene from Hamlet, then goes through Gene Gautier’s The Girl Spy Before Vicksburg, The Car of Death starring Helen Holmes, and the Chinese Fan episode of Mary Fuller’s Dolly of the Dailies, finishing with several parts of The Hazards of Helen, starring both Holmes and Helen Gibson.

Camelia La Texana

Pearl White: The Heroine of a Thousand Dangerous Stunts

American actress Pearl White was dubbed “Queen of the Serials” for her roles in some of the most popular episodic cinema productions. Beginning in 1914 with The Perils of Pauline, she was a pioneer of action heroine roles, famous for doing her own stunts, regardless of the risk. The following interview with her was originally published in the September 1921 issue of The American magazine, and offers a glimpse into the lost world of movie-making, almost a century ago.

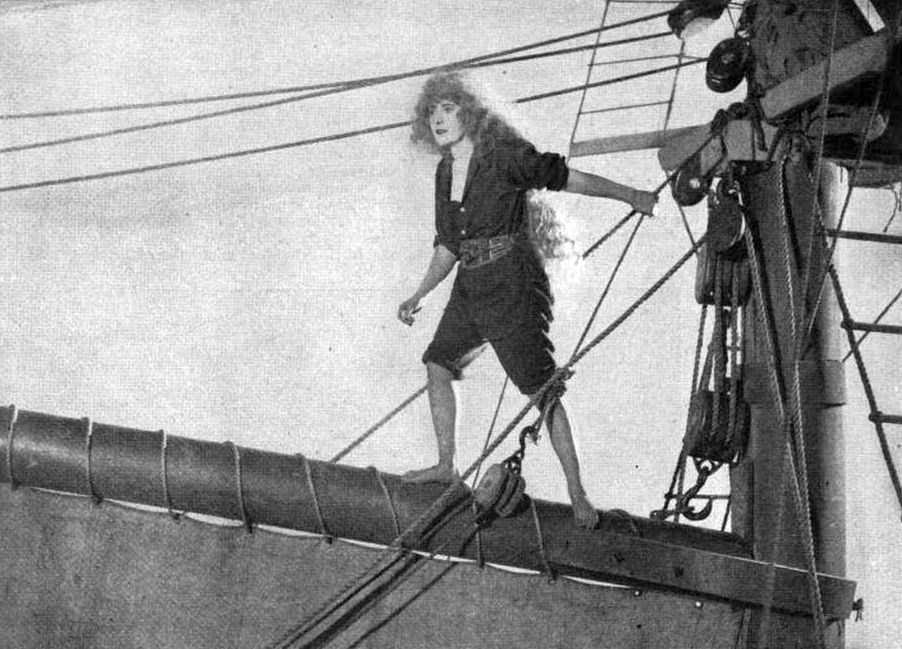

This picture shows Miss White walking the pole at the top of a ship’s mainsail, fifty feet or more above the deck. If she had slipped and fallen, she undoubtedly would have been killed. Once, when she was visiting the battleship “Mississippi,” the sailors begged her to do a “stunt.” Whereupon she climbed to the top of the forward “haystack” mast, the only woman who ever did it on any battleship.

Pearl White’s name is a synonym for courage and daring; yet she says she is “a born coward.”

“I have always been afraid,” she declares; “but I would be ashamed to let fear rule me”

By Mary B. Mullett

Pearl White is one of the most amazing human beings I ever have encountered. As I was leaving her dressing-room at the Fox Film Corporation studios in New York, the man who had arranged the interview asked me what I thought of her. “She’s a wonder!” I said. “Yes,” he agreed. “And the most remarkable thing about her is that she is a living wonder. She has done enough hair-raising stunts to kill half a dozen ordinary girls. Of course, she is doing only regular feature pictures now. No more stunts!… Well—that is—”

He hesitated a moment; then we laughed. No more stunts? That was a joke. She has been in danger over and over again during the past year; and she will keep on doing that sort of thing, because she is “that sort of girl.”

“The perils of Pauline” made Pearl White famous as a “stunt” star. Then came “The Exploits of Elaine,” “The Iron Claw,” “The Fatal Ring,” “The Lightning Raider,” and other serial pictures. All over the world, her name became a synonym for courage and daring.

When we sat down to talk, I looked at her curiously. She has fine dark eyes, sensitive nostrils, an expressive mouth. There isn’t an ounce of superfluous flesh on her body. In manner, she is as frank and unaffected as a boy. In fact, when she was talking about some of her experiences, she often said, “There was another boy in the company” — as if she herself were a boy.

As I thought of the things she has done, they seemed incredible; and I asked the question which millions of persons who have seen her on the screen must have wanted to ask:

“Aren’t you ever afraid?”

“Afraid!” she said. “I’m always afraid! I’ve been afraid all my life!

“I was born in Green Ridge, a little Missouri village which doesn’t exist now. My mother was an Italian and my father was Irish, although he was born in this country. An Irishman, you know. isn’t afraid of the devil himself. But as for my brother and me, we were a beautiful pair of cowards.

“I was afraid of people, afraid of animals, afraid of the dark – afraid of everything! We were the poorest children in town, and that’s saying a good deal. Half of the time I didn’t have any shoes. And because we were poor and because we were cowards, all the other kids picked on us.

“I was afraid of people, afraid of animals, afraid of the dark – afraid of everything! We were the poorest children in town, and that’s saying a good deal. Half of the time I didn’t have any shoes. And because we were poor and because we were cowards, all the other kids picked on us.

“When I was only five years old, I played in ‘Uncle Tom’s Cabin’ with a strolling company that came to the village. Of course the other children wanted to do it, and because I got the chance and they didn’t, they were jealous. So they picked on me all the more. But I was such a coward that I never stood up to them. I’d hit back and then run – with the emphasis on the ‘run’. My brother did the same.

“When my father found this out, he got a strap and told us that if he ever heard of our being beaten by any of the children, or of our running away from them, he would give us an extra whipping himself. He did it too. And soon we learned that it was better to stand up to the children than to take our punishment at home

“When my father found that we were afraid of the dark, he set out to cure us of that too. At night he would send us on errands, each of us in a different direction. Often I’ve had to go half a mile, or more, out on some dark and lonely road. And I couldn’t pretend that I had done it; for he made me go after something which I had to bring back as proof that I really had gone where I was sent. He used to send me to the dark cellar for things, and up0stairs to the dark bedrooms. He meant it all right, but it didn’t cure me. I am still afraid of the dark.”

“And do you mean that now, when you do dangerous stunts for the pictures, you are afraid?” I asked.

“I do mean it!” she said emphatically. “I am petrified with fear. Cold! Frozen! Terrified! I tell you. I’m a coward.”

“Yet you never have someone take your place when there is a particularly dangerous stunt to be dangerous gone through with, do you?”

“You mean, do I ever have anyone ‘double’ for me, as we call it in moving pictures? No, I never have done that.”

“Why not?”

“Well, there’s a sort of fascination about it, for one thing. And after it’s all over, there’s a kind of exhilaration in having done it! I suppose it means more to me because I am afraid. You say to yourself ‘I thought I couldn’t go through with it, but I did!’ And that makes you feel good inside.

“Then, too, you must remember that when I began working in the pictures, I didn’t count for much personally. I wasn’t famous. When I did ‘The Perils of Pauline’ it was the picture that drew. If I broke my neck, or my back, or spoiled my poor face, they could get somebody else. After I had made a reputation, it was different. My name counted then, so then they did want me to have someone double for me in any very dangerous stunts.”

“Why didn’t you do it?”

“Partly from pride and partly because, for some reason, I never seem to get hurt doing the big things.” She rapped on the wooden table beside her. “I’ve done a million stunts. I’ve been hurt over and over again. But” (rap, rap, rap) “it never happened when I was doing what looked really dangerous.

“At least, not since I have been in moving pictures. When I was a young girl, I traveled with the circus for a while doing a trapeze act. Once, when I was hanging by my right hand, the ligaments in my wrist pulled out, and I dropped. I fell on the edge of the net, rolled out of it, came down on my shoulder, and broke my collar bone.

“Once I went into the pictures, my serious injuries have come through some slight mischance; not during a big moment of danger. For instance, in one picture I was bound with ropes, my hands tied behind me, and I was left in the cellar of a building, which was then set on fire. The hero was to rescue me just in the nick of time.

“Everything went smoothly until he tried to carry me up the stairs. I was still bound, and he had thrown me over his shoulder, with my head hanging down his back. He had carried me up six or seven steps when he lost his balance, and toppled over backward. I couldn’t help myself, so I struck on the top of my head, displacing several vertebra.

“Everything went smoothly until he tried to carry me up the stairs. I was still bound, and he had thrown me over his shoulder, with my head hanging down his back. He had carried me up six or seven steps when he lost his balance, and toppled over backward. I couldn’t help myself, so I struck on the top of my head, displacing several vertebra.

“That was the worst hurt I have received. The pain was terrible. For two years I simply lived with osteopaths, and to this day I have some pretty bad times with my back. Yet you wouldn’t have called that a dangerous stunt, or any stunt at all, so far as I was concerned.

“In another picture, I was thrown into the water from a ferryboat just as it was coming into the ferry slip. The slip is enclosed by high walls of solid planking, reaching down into the water, and it would look as if I could not escape being crushed between the boat and the wall of the slip. But at the crucial moment a rope is thrown to me, I catch it, and am pulled out just in time to miss death.

“Well, the program was carried out all right. I was thrown into the water; then, while the ferry—which looked to me as big as the Woolworth Building—came slowly closer, the rope was thrown to me. I had been afraid I would miss it; but I didn’t and they pulled me up onto the dock just in time.

“Then, as I lay there in somebody’s arms, with my eyes closed, I said, ‘Well, boys! I did it! And with that, I threw out my left arm in a gesture which anyone might have made in those circumstances. As I let it drop, my hand went over the side of the dock; and at that moment the ferryboat crashed in, caught my hand, and broke the bones in all the fingers.

“Do you see? The dangerous part of the stunt went off all right. And then, when it was all over and I was ‘safe,’ I did a simple little thing and got my hand smashed.

As the heroine in “The Black Secret,” Pearl White has a fight with a ruffian who throws her down a flight of stairs. She has had many of these struggles on stairs, one of them continuing down several flights and resulting in her jaw being dislocated.

“In one picture I had to fight with another boy down several flights of stairs. It was real fighting, too; rolling over and over, striking our heads against the banisters and the wall, struggling all the way. I accidentally knocked the other boy unconscious; but aside from that and the inevitable bruises, neither of us was hurt.

“Then we wound up with what looked like a comparatively simple stunt: he was to be sitting on a low bench in the hall below, and I was to jump over the banister from above and land on him. Then we were to roll off onto the floor and continue our fight. It wasn’t a very big jump, and the bench he was on was only about two feet high.

“I made the jump all right, landed on him, and we rolled off. But as we went over, his hand happened to catch me just right, at the side of my neck, and dislocated my jaw! Again the big stunt had gone through safely, and my injury had come in some unexpected mischance.

“Why, I was standing on the curb one day, waiting for a street car. Millions of people do that and never think of danger. Neither did I. But when I stepped off— only about a six-inch step—I somehow fell and broke my ankle.

“When I first went into pictures, we were making some cowboy scenes up in the Bronx, right near New York. I was a good rider; in fact, it was my riding that got me my chance at moving picture work. Although I was a ‘trap’ performer in the circus, I was crazy to be an equestrienne and was always riding the horses around ‘the lot’ in my spare moments. Later, I traveled with a theatrical company, doing one-night stands in the Southwest. And every time I had a chance, I would get a a horse and go cavorting around the country.

“In that way I learned to ride pretty well. When it came to the wild riding necessary in the pictures, I did all kinds of stunts. I’ve been thrown dozens of times; and while I have been knocked out repeatedly, I never was badly injured.

“One day, in making those Wild-West pictures in the Bronx, I was doing a perfectly simple bit of work, just straight riding. However, the sun was in my eyes and 1 didn’t notice a little sapling ahead. It wasn’t thicker than my wrist, anyway. But my pony dashed by so close to the sapling that it struck my knee and broke my knee cap.

“So why worry about the big things? It’s the little ones that get me. There was the time, for instance, when we were making pictures down in Florida. In one scene, I was to jump off a moving steam yacht. And, by the way, I want to say this: I never do a serious stunt without first studying the possibilities of danger, so as to avoid an accident if I can.

“In this case, for example, the director told me to jump from the rail of the yacht, at the middle of the boat, which was to continue steaming ahead until it moved out of the picture. I was to have a life preserver in my hand and was to keep hold of it as I struck the water.

“Well, I did some thinking on my own hook. And then, when the director had gone off to the tug, where the camera man was, and which was to keep abreast of us so as to get a long shot of the whole performance, I hunted up the captain.

‘”Do you know from what part of the boat I am to jump?’ I asked him.

“Why, from toward the stern,’ he said.

‘”Not at all!’ I explained. ‘I’m to jump from the middle of the boat.’

“‘But you can’t do that!’ he said. ‘If I’m steaming ahead, the suction will carry you under the vessel.’

“‘I know that,’ I told him. ‘But if you stop your engine, I will get away, and your momentum will carry you out of the picture all right. I’ll have somebody give you the signal when to stop.’

“I made another change, too. I realized that if I held onto the life preserver when I struck the water, my arm would get an awful wrench. So I let go of the life preserver just before I hit the water, and then caught hold of it again as I came up.

“But,” she went on with a touch of bitterness,”there was one thing which nobody had told me! Perhaps they did not know—certainly I did not know—what was in the water between the yacht and the tug. . . . Sharks! … I saw several of them around me as I swam to the tug; and I was too frightened then to do anything but swim—and pray. I did both as hard as I could.

“But,” she went on with a touch of bitterness,”there was one thing which nobody had told me! Perhaps they did not know—certainly I did not know—what was in the water between the yacht and the tug. . . . Sharks! … I saw several of them around me as I swam to the tug; and I was too frightened then to do anything but swim—and pray. I did both as hard as I could.

“Again luck was with me. Or maybe it was Providence. I believe in praying. I confess that I don’t do enough of it, except when I am frightened. But I’m scared so often that I keep in pretty good practice.

“Anyway, I escaped that time, when the risk was really a serious one. And then the next day, when I was doing a scene on the beach, where you wouldn’t have thought I could get hurt if I tried, I stepped on a shell, cut my foot, had blood poisoning, and was laid up for three weeks.

“At one time, I thought I wanted to be an aviator; so I had a couple of months of off-and-on instructions; off and on as to lessons, I mean; for I never went ‘off’ the ground. About that time we were making a picture in which the hero was cast away on a desert island. The place was really Staten Island, in New York Harbor; but there are parts of it which are deserted as anything you will find in the South Seas.

‘They wanted a scene where the heroine lands on the island in an airplane, rescues the hero, and flies away with him. They thought I would double for this scene; have somebody else actually fly the machine for the long shot of it in the air. They could take close-ups of me starting it and landing.

“But I insisted on making the whole trip. The machine they had was an old one-passenger Wright biplane, so I had to go alone. I never had been in the air by myself. My only experience hid been running the machine on the ground. But the director didn’t know this, and I didn’t tell him.

“As a matter of fact, I made the flight safely. But as I came down to make the landing, I miscalculated the distance and ‘landed’ in the water! If it had been a hydroplane, I might have been all right. But it wasn’t. And when the machine struck, the engine simply turned over with a jump, and the whole thing sank. Luckily I got out and swam ashore. Now, that really was a dangerous stunt, because I didn’t know how to fly an airplane. Yet I wasn’t hurt.

“I had another very unpleasant experience in the air. They wanted a scene showing the heroine taking a little pleasure ride in a captive balloon, such as you will find at many amusement parks. But in this case the villain was to cut the ropes and set the balloon adrift.

“We staged the scene at Palisades Park, across the Hudson from New York City. There was no one in the basket but the aeronaut and myself. According to our plan, after the ropes were cut the balloon would go off over New Jersey, and we would descend after being in the air about fifteen minutes.

“We staged the scene at Palisades Park, across the Hudson from New York City. There was no one in the basket but the aeronaut and myself. According to our plan, after the ropes were cut the balloon would go off over New Jersey, and we would descend after being in the air about fifteen minutes.

“But about ten minutes after we were cut loose, a sudden storm broke. It was April and this was a good old-fashioned April thunderstorm, with rain, wind, lightning, and all the trimmings. I don’t suppose it lasted over twenty minutes, but they seemed to me like twenty years. We were drenched to the skin and half frozen.

“In order to rise above the storm, we threw out ballast and got up to about five thousand feet. Then, when the storm passed and we wanted to come down, we found that we were over New York City! We did not dare to descend there. The balloon might land on the edge of a twenty-story building and tip us into the street.

“For three hours and a half we were in the air; most of the time over the city, although once we were carried two miles out to sea. But we didn’t dare to come down in the water, of course. Most of this time, I was busy tearing a long roll of tissue paper in pieces and dropping them over the side of the basket. As they fell, they would show in which direction the currents of the air below were moving. There seemed to be different levels, on which the currents moved in different directions. At first, the aeronaut would throw out ballast in order to rise; or would let some of the gas escape, in order to descend.

“In this way we jockeyed around, trying to get into a current which would carry us to a safe landing place. But we couldn’t make it. Finally, all the ballast was gone and, to complicate the situation still more, the bag was leaking gas. We had settled down until we were only about a thousand feet above the roofs of New York and were slowly sinking still nearer to them.

“But my luck held; for finally the wind veered, carried us clear of the city, and we came down safely. But that was the longest three hours and a half I ever put in.

“As a rule, when you are doing picture stunts, there isn’t any long-drawn-out suspense. It generally goes with a rush, and the danger is over before you have time to lose your nerve.

“For instance, I have walked a board across an open court between two twelve-story apartment houses. The board was perhaps fifteen feet long and was laid from one roof to the other. If I had made a misstep, or had lost my balance, I should have fallen those twelve stories to the paved courtyard below.”

“Perhaps you’re not afraid of being in high places,’ I said.

“Afraid is too mild a way to put it!” was the earnest response. “I am almost rigid with terror. If I looked down, I should be lost. I am a Catholic, you know; and I never do one of these stunts that terrify me, without saying a ‘Hail, Mary’ as I start.

“Often I have had to jump across a four-foot chasm between two buildings. Four feet isn’t very wide a jump, when you have a running start. But suppose my foot slips, or my toe catches, just as I take off. It that happened—Well, it never has.” Again she rapped on the table beside her.

“Are you superstitious?” I asked.

“No! I believe it’s unlucky to break a mirror—because then you’ll have to buy a new one. I think it would be unlucky to fall in front of a street car—because you might be run over. But I don’t have any so-called mascots, or things that I think bring me luck. I try to be careful, and then I let it go at that. The reason I rap on wood is simply because other people do, and I have picked it up from them.

“Experiences like those I have had make you feel that you will die when your time comes—not before. Anyway, the thing I dread is not death, but being maimed or disfigured. That’s another reason why I prefer the big risks. If I missed my footing and fell a hundred feet, it would kill me. If I fell twenty feet, I might only be crippled for life, or hopelessly disfigured.

“Yesterday we were doing a scene here in the studio and I had to fall backward through a large picture hanging on the wall. It was a fall of less than six feet. It didn’t look like much of a stunt, but I’d rather have jumped off a seventy-foot cliff into the water than have done that little backward tumble onto the floor. Yesterday we did the scene from the front. To-day we do it again from the back of the painting. And I’m afraid! Honestly I am.”

“You speak of jumping off a seventy-foot cliff,” 1 said. “Have you ever done it?”

“You speak of jumping off a seventy-foot cliff,” 1 said. “Have you ever done it?”

“Oh yes, several times. There’s a cliff that high up at Saranac Lake, and I’ve jumped from it for three different pictures. I’m not good at jumping into the water, either. I can drop all right and strike the water with my toes, which is the proper way. But when I jump, I come down on my heels; and that gives a bad jar to the spine.”

“Of course you are a good swimmer?” I asked.

“I can swim pretty well now. But when I first did stunts where I was thrown into the water, I couldn’t swim a stroke. If there had been any hitch in the program, I should have drowned. But you know,” she laughed, “a company has a very good reason, aside from any considerations of humanity, for wanting to save the actor. Especially if the actor is a star.

“Suppose half the scenes of a picture have been made. They have cost a lot of money. And suppose I am the star who is featured in the play. If I am killed, they can’t substitute somebody else; so they try to protect themselves by having all the scenes which are not dangerous made first. The ones in which the star risks his or her neck are done last. Then, if anything does happen, someone can double for the disabled or deceased star, and the picture can still be shown. The close-ups nave already been made. And in the long shots the double will not be recognized.

“For instance, suppose it is that seventy-foot leap up at Saranac. Three separate views of it are taken. There is a close-up of me, just as I am jumping off, and another close-up as I strike the water. Then there is the long shot. To make this, the camera is far enough away to show the whole height of the cliff, and the actual leap from start to finish. There can be no fake about this. The seventy-foot jump is actually made. But the figure is so far away that you can’t recognize the features.

“The close-ups are probably not made at the real cliff at all. In the one which shows the beginning of the leap, I am jumping from a ledge into a net, or perhaps only about ten feet into the water. For the close-up of me striking the water, I have made only a short jump from a bank or a platform, which does not show in the picture.

“Now suppose all the scenes have been made, except the long shot of the actual seventy-foot leap. And suppose something happens to me when I do make that leap. If I am killed, or injured, they can find an expert diver, dress him in my clothes, put a wig on him that will be like my hair, take the long shot—and the picture is saved. So that’s why the dangerous stunt is kept until the last.”

“What was the worst experience you’ve ever had?” I asked.

She thought for a moment, then gave a little laugh.

When a bunch of moving picture German soldiers thrust their bayonets almost within pricking distance of her throat, Pearl White could only shut her eyes and hope that the men behind those particular guns were good judges of distance.

“I think the hardest thing I ever did was during the drive for the Victory Loan. The New York Fire Department sent out one of its huge ladder trucks, with a crew to operate it, and I went along. They would raise the ladder almost straight into the air—not leaning it against a building —and I climbed it, one rung for each subscription from the crowd below. I think there were seventy-two rungs. I went to the very top; then over the top, and down the other side, one rung at a time.

“The worst thing about it all was the slowness: of it. I used to stand on that ladder, simply praying that somebody would take another bond—and take it quickly! People in the crowd, or in the windows, would call to me. Apparently, I would look down and bow. But I had to shut my eyes when I did it. We went all over the city with that awful ladder.”

“But why did you do it, if you were so frightened?”

“I don’t know—one doesn’t want to be a quitter. Being a coward is one thing. You can’t help that. But acting the coward is very different. I’m not ashamed of feeling fear. But I would be ashamed if I let my fear rule me. I guess that’s it.

“There was another time when I did something which absolutely terrified me, and which wasn’t done for the pictures, or for anything as worth while as patriotism either. It was just a ‘publicity’ stunt. I believe it was in 1915, when one of the picture companies was moving into a new building. The scheme was this; I was to climb down the front of the building to an electric light sign, then down this sign to a painters’ scaffold, and paint one letter of the company’s new sign. Our publicity manager had got a steeplejack to make the attempt first, and the steeplejack had proved that it could be done.

“But the manager began to get cold feet as the day approached. So he arranged for me to wear a harness under my clothing and to have strong wires attached to this harness. The wires would not be visible to the crowd in the street; and they would be fastened to something on the roof and ‘paid out’ as I climbed down. Then, if I lost my footing, or my head, or my nerve, I wouldn’t be killed.

“But when the time came, I found that the manager had let a lot of newspaper men come up where I was to start! Well! It would be a fine story, wouldn’t it, to tell about me! How I was all tied with wires. So I told the manager that I wouldn’t have the wires used. It would simply ‘make a Chinaman’ of me.

“‘Well then,’ he declared, ‘you mustn’t go! We’ll call the whole thing off. We can say that you are sick.’

“I was sick; sick with fear! But if I backed out, I should ‘make a Chinaman’ of myself. So I insisted on going through with it.

“I got to the electric sign safely and began to climb down that. It was one of the meanest things I ever saw—that sign. It shook and swung and behaved as if it were bewitched. But I managed to reach the scaffold all right. While I was climbing down, I looked up occasionally, and I could see the manager, leaning over the top, watching me. His face was dead white.

“I painted the letter as I had been told to do; but before I was half through, the manager began calling me to come back. 1 paid no attention to him. I was safe where I was, and I was in no hurry to take the return trip. I was glad he was suffering. I said to myself, ‘He got me into this. Now he can worry a while.’

“I finished the letter on the sign, and then I deliberately painted my own initials on the wall of the building. I made them good and large, too. It was the Saturday before Easter, I remember. I knew they would have to stay there over Sunday, anyway, and I thought I might as well get what I could for myself out of the experience. I think I must have been down there twenty minutes. Then I climbed back. When they helped me over the ledge at the top—the manager fainted.’

“And you?” I asked.

“Oh, I didn’t faint, if that’s what you mean. I never have fainted. I’ve been knocked unconscious a good many times, but I’ve never fainted.”

“You said you were afraid of animals. Have you ever done stunts with lions and other wild beasts?” I asked.

“Yes, of course. Last year we were making a picture down in Cuba, and they had a famous lion, called Jimmie, for some of the scenes. In one of them, I went into a sort of cave, which was already occupied by Jimmie. I sat down on the sand, according to directions, and was proceeding with the action, when Jimmie suddenly leaped at me. Perhaps I swerved aside. At any rate, he missed me and struck the sharp edge of a rock, cutting his paw. He stopped a minute to lick the cut—and then turned to attack me again. But before he could reach me, the trainers were on him.”

“No more lions for you, after that, I imagine!” I said.

She looked at me with the expression I had noticed so often while we were talking, a curious mixture of nonchalance and intensity.

“Not for half hour or so,” she said; “then we did the scene again. Fortunately, Jimmie behaved better that time. Or maybe he’d lost his taste for me.”

‘If the photographer went on turning the camera handle when Jimmie leaped at you, it must have made a great picture,” I said. “Do they often get these thrilling accidental scenes?”

“They happen once in a while, but I never have known of an accident picture that could be used. You see, they never fit into the story. The time I sank the airplane, for instance, the picture couldn’t be used, because the story required me to land safely and to rescue the hero from his desert island. It is always that way. The accident spoils the story.

“Once I had to make a flying leap from a moving automobile to the running board of another machine which was racing abreast of it. I missed the running board and fell. I had on a leather coat, which caught in the wheel, and 1 was carried for at least one complete revolution before the machine could be stopped. But the picture of the accident couldn’t be used, because in the story I made the leap successfully.”

“Speaking of automobiles, I must tell you of the most wonderful nine days I ever spent. It was one summer during the war. I was sick of New York, fed up with Broadway, disgusted with everything and everybody. We had just finished a picture and I had a six-weeks vacation ahead of me. The very first night of it, I packed a bag, had a roll of blankets put into my car, and started out alone to get away from all the noise and glare and sordidness of the city into the good clean country.

“Speaking of automobiles, I must tell you of the most wonderful nine days I ever spent. It was one summer during the war. I was sick of New York, fed up with Broadway, disgusted with everything and everybody. We had just finished a picture and I had a six-weeks vacation ahead of me. The very first night of it, I packed a bag, had a roll of blankets put into my car, and started out alone to get away from all the noise and glare and sordidness of the city into the good clean country.

“I told you that I was afraid of the dark. I am! But I slept every night under the car, in some lonely field away from the road. One night I was frightened half out of my wits when a cow almost stepped on my arm, which was sticking out from under the machine. I used to drive at night, too; and when the road ran through woods I was in terror every minute of the time. But I kept on going. I followed no set route, but wandered around in all directions.

“The fourth day, I turned into a little by-road up near Schenectady and came to a shabby farmhouse. The yard seemed to me to be alive with dogs, which set up a tremendous barking. The rumpus brought a woman to the door, and I asked her for a glass of water. I hadn’t been near a hotel since I had left New York. It had rained more than once; but I had a rain coat and had kept right on going. I would buy food at village stores and eat it when I came to some quiet bit of road. It was a wild proceeding; but I was happy, out under God’s stars, as I told myself, and all that sort of thing.

“Well, the woman asked me if I wouldn’t get out and stay a while. I had been sick of people—but not of people of her sort. So I got out and we two sat there on her little porch and talked for five hours! She was wonderful. Uneducated, so far as schooling went; but with a philosophy of wisdom of her own. I never have felt so small as I did sitting there and listening to her.

“We talked of everything; of right and wrong, of why people are what they are, of what is really worth while, and of what is only on the surface and doesn’t count in the long run.

“It was a strange experience; and, for me, a very wonderful one. I had been half inclined to come back to New York. But after my talk with her, I stayed out five days longer. I think I would have spent the whole six weeks that way if I hadn’t gone to Albany. After nine days of roughing it, I went to a hotel there to have a few hours in a bathtub and to replenish my limited supply of clothing. As luck would have it, I met friends there, and they persuaded me to give up what they considered my mad escapade. But those nine days will always be literally the ‘nine days wonder’ of my life.”

Wanted: Seasons one and two

★★★

“Where women glow and men plunder.”

Not to be confused with the Angelina Jolie movie, this Australian TV series kicks off with an incident at a bus-stop, where Lola (Gibney) and Chelsea (Hakewill) are witnesses to a bloody battle, in which Lola accidentally shoots one of the participants. Both women are abducted by the survivor, but he in turn is gunned down by a former policeman. The pair high-tail it from the scene in the car, and discover it contains a hold-all carrying a large quantity of cash. Unable to trust the authorities – not least because both women have legal clouds hanging over them – they are forced on the run. In pursuit is the owner of the cash, Morrison (Phelan), and his minions, led by corrupt copper Ray Stanton. For Lola and Chelsea are entirely right in their paranoia.

Not to be confused with the Angelina Jolie movie, this Australian TV series kicks off with an incident at a bus-stop, where Lola (Gibney) and Chelsea (Hakewill) are witnesses to a bloody battle, in which Lola accidentally shoots one of the participants. Both women are abducted by the survivor, but he in turn is gunned down by a former policeman. The pair high-tail it from the scene in the car, and discover it contains a hold-all carrying a large quantity of cash. Unable to trust the authorities – not least because both women have legal clouds hanging over them – they are forced on the run. In pursuit is the owner of the cash, Morrison (Phelan), and his minions, led by corrupt copper Ray Stanton. For Lola and Chelsea are entirely right in their paranoia.

There have been two seasons to date, each of six 45-minute episodes, making for a relatively quick watch. The story does occasionally strain belief in a couple of areas, with the long arm of coincidence playing more of a part than it ideally should. Chris also would like you to know that none of the dramatis personae should submit their applications to MENSA any time soon [or put another way, I lost track of the numbers of times, she yelled “STU-pid…” at the screen]. But I was largely willing to overlook these flaws, in the service of two great lead characters, whose interaction is a joy to watch. Lola is the tougher one out of the box, for reasons that become apparent, and more likely to engage in direct action, right from the very beginning. She’s driven by fierce loyalty to her family, especially her son. Chelsea, is almost the exact opposite: a mouse who slowly finds her inner lion, who is both smart and dumb at the same time, without it seemed a contradiction.

The first season ended in a pure cliff-hanger, Lola getting a call to be told, “Did you think this was over? We have your son.” Consequently, the second broadens the scope of the show considerably, with Lola haring off to recover and try to protect him (cue Chris with the “STU-pid…”, as the young man makes another in a series of questionable decisions!). She’s also after a key piece of evidence that will put Morrison away, allowing her and Chelsea to return to something approaching a normal life. The setting expands out too, from Australia to include both Thailand and, in particular, New Zealand, where the landscapes are almost a distraction on the “Tourist Board promotional film” level. [Seriously, at one point, a villain even pauses in his pursuit to take a selfie with the scenery]

The strength of the show though, remains the pairing of Gibney and Hakewill; the former’s age (in her fifties) makes her an interesting rarity in our genre, where youth dominates. She was also co-creator of the show, along with her husband – the lesson here being, if you want a good role, write it yourself! Despite obvious comparisons I’ve seen to Thelma & Louise, this does a better job of digging into the depths of the central pair, albeit with few scenes even approaching Ridley Scott’s style. Perhaps Season 3 can have a little less reliance on unfortunate happenstance, rather than direct action. For example, we do not need anyone else being disposed of, by falling onto a pointy branch…

Created by: Rebecca Gibney, Richard Bell

Star: Rebecca Gibney, Geraldine Hakewill, Stephen Peacocke, Anthony Phelan

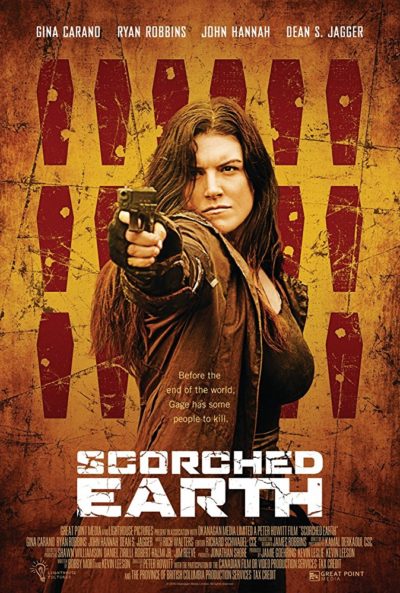

Scorched Earth

★★★

“Future imperfect.”

This workmanlike effort, if not particularly memorable, does at least cross two genres not frequently combined: the Western and the post-apocalypse movie. For it takes place in a world where global warming and other stuff have created a poisoned wasteland. Consequently, the currencies of choice are water purification tablets and silver, the latter being the raw ingredient in the air filtration masks which have become essential. Using vehicles powered by fossil fuels is totally outlawed, and those who do have rewards placed on their heads, attracting the attention of bounty hunters.

This workmanlike effort, if not particularly memorable, does at least cross two genres not frequently combined: the Western and the post-apocalypse movie. For it takes place in a world where global warming and other stuff have created a poisoned wasteland. Consequently, the currencies of choice are water purification tablets and silver, the latter being the raw ingredient in the air filtration masks which have become essential. Using vehicles powered by fossil fuels is totally outlawed, and those who do have rewards placed on their heads, attracting the attention of bounty hunters.

One such is Atticus Gage (Carano), who hears from former partner, Doc (Hannah) of an outlaw town, Defiance. This is run by Thomas Jackson (Robbins), whose bounty exceeds them all. Inevitably, Gage heads to the town to take Jackson out, adopting the identity of one of her previous targets, and insinuating herself into his posse. And equally inevitably, he turns out to have a connection to a dark incident in Gage’s past, when not plotting to re-open a nearby silver mine, the ore being dug out by pilgrims kidnapped off a nearby trail.

Carano has struggled to repeat the success of her (effective) feature debut, Haywire, with cinematic supporting parts in the likes of Deadpool and Fast and Furious 6 alternating with straight-to-video starring roles, such as In the Blood. These have been best when she has been allowed to concentrate on the physical aspects which are her strength, and the same goes here, right from the first moment we see her, riding into shot and dragging a coffin behind her, in a nice nod to the original Django. However, if she’s ever going to go further, she needs to show significantly more development as an actress. Haywire was now seven years ago – not that you’d know it from her performance here, especially when put alongside someone like Hannah.

I did like the overall setting, despite odd gaps in logic: sometimes people need to wear masks, at other times they don’t. It’s a universe which I’d have been interested to see explored some more, perhaps in an extended format, such as a TV series. This could have answered questions such as, where are those pilgrims going, anyway? I also appreciated how Gage has the ability to be a complete bad-ass, on more than one occasion showing absolutely no qualms about shiving or shooting those who might be about to blow the gaff on her assumed identity.

The tone is likely best summed up by a sequence in which Gage finds herself sealed into her own coffin and tossed off the side of a cliff. Naturally, she survives, staggering back to Doc, who patches her up, allowing the pair of them to return to Defiance, for a final grandstand(ish) shoot-out. It’s all thoroughly implausible, yet somehow, is in keeping with the pulp/comic-book aesthetic for which the makers seem to be aiming. I can’t say it’s entirely, or even largely, successful there. Yet it’s just enough to leave me back on the hook for whatever Carano does next, hoping for better.

Dir: Peter Howitt

Star: Gina Carano, Ryan Robbins, John Hannah, Stephanie Bennett

A Deadly Game

★½

“An arrow escape.”

Winner of the “Most misleading DVD cover of the year” award, the gap between expectation and reality has rarely been wider. It starts off promisingly enough, with young woman Kayla (Fairaway), carrying a bow and running away from a man in a car. She’s rescued by a passing motorist, but they are run off the road by their pursuer. There’s then a flashback, to explain how these events came about. Which would be fine, except for the flashback lasting close to an hour and a quarter of thoroughly mind-numbing chit-chat, before anyone even picks up a bow in anger. It’s not exactly the Hunger Games wannabe the sleeve is trying to suggest.

Winner of the “Most misleading DVD cover of the year” award, the gap between expectation and reality has rarely been wider. It starts off promisingly enough, with young woman Kayla (Fairaway), carrying a bow and running away from a man in a car. She’s rescued by a passing motorist, but they are run off the road by their pursuer. There’s then a flashback, to explain how these events came about. Which would be fine, except for the flashback lasting close to an hour and a quarter of thoroughly mind-numbing chit-chat, before anyone even picks up a bow in anger. It’s not exactly the Hunger Games wannabe the sleeve is trying to suggest.

One of the alternative names, Deadly Spa, is far more accurate, even though it’s a title more likely to raise a smirk than a rush of adrenaline-charged excitement. Kayla is at the spa in question – ‘The Source’ with her mother, Dawn (Pietz), having convinced Mom she needs a break. At first, the place seems beyond perfect: all meditation rooms, power food breakfasts, toxin-cleansing saunas, and of course, no cell-phones allowed. Though Kayla has a yearning for a cheeseburger, which she guiltily admits to sympathetic (and hunky!) spa employee, Brett (Werkheiser).

Like most things in Lifetime TV movies which seem too good to be true, this is too good to be true. In particular, spa owner David James (Whitworth) has more in common with David Koresh than his customers should expect. He takes a shine to Dawn, and successfully pulls the wool over her eyes. Kayla is nowhere near so easily convinced, not least because she has seen David’s more psychotic side. When her mother finally sees the light as well, the two try to escape, planning to divulge David’s dirty little secrets to the authorities. If you’re well-read on cult leaders like Jim Jones, you’ll know that, to David, it makes them a problem. The solution initially involves tying Kayla up in an attic and inflicting low-rent brain-washing techniques on her. It doesn’t take. This is my unsurprised face.

Eventually – and, boy, do I mean “eventually” – this brings us back to where we came in. It takes so long, that I was beginning to feel I was the one held captive against my will, though unfortunately without any of that nice Stockholm syndrome kicking in. [And the sooner the PTSD kicks in and erases the whole movie from my memory, the better] First mom, and then the daughter, use their archery skills, miraculously picked up after little more than two arrows, to defend themselves. It’s just enough content – along with Mom’s miraculous and unannounced judoka talents, allowing her to flip one of David’s henchmen off a cliff – to allow this to qualify for the site. However, this review should be considered far more of a warning, than any kind of endorsement. I’m sure the place will be getting a one-star review on Yelp as well.

Dir: Marita Grabiak

Star: Amy Pietz, Tracey Fairaway, Johnny Whitworth, Devon Werkheiser

a.k.a. Zephyr Springs and Deadly Spa

The Fire Beneath The Skin series, by Victor Gischler

Ink Mage

Literary rating: ★★★½

Kick-butt quotient: ☆☆☆

The small duchy of Klaar has been impervious to invasion, due to a secure location offering limited access. But when betrayal from within leads to its fall, to the vanguard of an invading Perranese army, heir apparent Rina Veraiin is forced on the run. She is fortunate to encounter one of a handful of people who know how to create mystic tattoos that will imbue the recipient with magical abilities. With her already significant combat skills radically enhanced, and her body now also blessed with a remarkable talent to heal, Rina can set about trying to recover her domain. It won’t be easy, since the king is not even aware the Perranese have landed. But she has help, albeit in the motley forms of a stable boy – sorry, head stable boy – a gypsy girl and a noble scion, whose charm is exceeded only by his ability to irritate.

The small duchy of Klaar has been impervious to invasion, due to a secure location offering limited access. But when betrayal from within leads to its fall, to the vanguard of an invading Perranese army, heir apparent Rina Veraiin is forced on the run. She is fortunate to encounter one of a handful of people who know how to create mystic tattoos that will imbue the recipient with magical abilities. With her already significant combat skills radically enhanced, and her body now also blessed with a remarkable talent to heal, Rina can set about trying to recover her domain. It won’t be easy, since the king is not even aware the Perranese have landed. But she has help, albeit in the motley forms of a stable boy – sorry, head stable boy – a gypsy girl and a noble scion, whose charm is exceeded only by his ability to irritate.

Despite the young age of the protagonist, who is still a teenager, this isn’t the Young Adult novel it may seem. It’s rather more Game of Thrones in both style and content, with the point of view switching between a number of different characters. Some of these can be rather graphic, particularly the story of Tosh, an army deserter who ends up working as a cook in a Klaar brothel. But even this thread turns out more action-heroine oriented than you’d expect. For the madam gets Tosh to train the working girls in weaponcraft, so they can become an undercover (literally!) rebel force against the Perranese. Can’t say I saw that, ah, coming…

Gischler seems better known as a hard-boiled crime fiction author – though I must confess to being probably most intrigued by his satirical novel titled, Go-Go Girls of the Apocalypse! The approach here does feel somewhat fragmented, yet is likely necessary, given the amount of time Rina spends galloping around the countryside. It may also be a result of the book’s original format as a serial. However, it translates well enough to a single volume, and I found it became quite a page-turner in the second half. There, Rina readies her forces to return to Klaar, and take on the occupying forces, which have settled in for the winter.

The tattoo magic is a nice idea, effectively providing “superpowers” that can help balance out the obvious limitations of a young, largely untrained heroine. It is somewhat disappointing that, after significant build-up involving the Perranese’s own tattooed warrior, the actual battle between him and Rina seemed to be over in two minutes – and decided through an external gimmick, rather than by her own skill. In terms of thrills, it’s significantly less impressive than a previous battle, pitting her against a really large snake, or even the first use of Rina’s abilities, which takes place against a wintry wilderness backdrop – more GoT-ness, perhaps?

Such comparisons are unlikely to flatter many books, and this is at its best when finding its own voice, as in the tattooing, or the gypsies who become Rina’s allies. He does avoid inflicting any serial cliffhanger ending on us, instead tidying up the majority of loose ends, and giving us a general pointer toward the second in the three-volume series. Overall, I liked the heroine and enjoyed this, to the point where I might even be coaxed into spending the non-discounted price for that next book.

The Tattooed Duchess

A Painted Goddess

Literary rating: ★★★★

Kick-butt quotient: ☆☆☆

It makes sense to treat the second and third volumes in the series as a single entity. Ink Mage worked on its own as a one-off, with a beginning, middle and reasonably well-defined end, and the eight-month pause between installments was not a problem. Duchess and Goddess, however, really need to be read back-to-back. Mage ended with Rina Veraiin having recovered her family’s territory of Klaar, thanks largely to the magical tattoos covering her skin. But the new duchess is discovering that fighting to get territory is one thing, ruling over it on an everyday basis, quite another. Especially since the Perranese invaders repelled in the first volume, are on their way back with a vengeance. For their Empress Mee Hra’Lito needs a big win to keep control of things on her side of the ocean.

It makes sense to treat the second and third volumes in the series as a single entity. Ink Mage worked on its own as a one-off, with a beginning, middle and reasonably well-defined end, and the eight-month pause between installments was not a problem. Duchess and Goddess, however, really need to be read back-to-back. Mage ended with Rina Veraiin having recovered her family’s territory of Klaar, thanks largely to the magical tattoos covering her skin. But the new duchess is discovering that fighting to get territory is one thing, ruling over it on an everyday basis, quite another. Especially since the Perranese invaders repelled in the first volume, are on their way back with a vengeance. For their Empress Mee Hra’Lito needs a big win to keep control of things on her side of the ocean.

Rumbling in the background, and coming to a head particularly in Goddess, is a changing of the guard in the Kingdom of Helva’s divine pantheon, with the current incumbent as top god being challenged for that position. Disturbingly, the likely replacement is the god of war: never a good thing, especially when he can raise an army of unstoppable dead soldiers and send them after Rina and her allies. Dealing with both those threats, requires Rina to ink up some more. Since she’s otherwise engaged, that means sending expeditions to the furthest corners of the lands and beyond, to retrieve the templates needed for Rina’s power-ups. [Though part of the problem is, these don’t come with instructions, explaining what a tattoo will do…]

In particular, off to the Scattered Isles go stable-boy Alem, who carries a torch for Rina, and gypsy girl Maurizan, who is interested, both in Alem and getting some magic ink of her own. Meanwhile the noble Brasley and a new character, near-immortal female wizard Talbun, are exploring the depths – or, rather, heights – of the Great Library. This is a building so vast, it remains largely unexplored, with its origins and contents lost in the mists of time. Rina, meanwhile, is on a diplomatic mission, aimed at securing support for Klaar, only to be abducted by a group of Perran soldiers and their own mages, left behind when the army withdrew.

Especially in the second volume, poor Rina is largely relegated to a supporting role. The major threat to her is, not deities or monsters, but the arguably more insidious danger of an arranged marriage, necessary for the defense of Klaar. Maurizan becomes the action heroine focus, supported by members of the “Birds of Prey”, ex-prostitutes who have become the castle guard, as well as Talbun. It’s decent, yet almost inevitably, suffers from the bane of trilogies, “second volume syndrome”, lacking both a beginning an an end [I will say, for understandable reasons, explained by the author on his site]. It was originally published in serial format, so feels a bit episodic too, though I can’t say this impacted my enjoyment particularly much.

Especially in the second volume, poor Rina is largely relegated to a supporting role. The major threat to her is, not deities or monsters, but the arguably more insidious danger of an arranged marriage, necessary for the defense of Klaar. Maurizan becomes the action heroine focus, supported by members of the “Birds of Prey”, ex-prostitutes who have become the castle guard, as well as Talbun. It’s decent, yet almost inevitably, suffers from the bane of trilogies, “second volume syndrome”, lacking both a beginning an an end [I will say, for understandable reasons, explained by the author on his site]. It was originally published in serial format, so feels a bit episodic too, though I can’t say this impacted my enjoyment particularly much.

Rather than having to wait for the next part, as readers at the time had to do, I was able to head straight on into volume three. And Gischler redeems himself admirably for any flaws, with an excellent final volume. Rina has pretty much completed her set of tats, now possessing superhuman strength, speed and healing, as well as the ability to have anyone believe what she says, plus more. However, there’s a darker side to her talents, which becomes apparent to everyone when the Perranese lay siege to the port of Sherrik. With great power comes… scary responsibility, it appears: Rina has to make some unpleasant decisions about how far she is prepared to go, in order to repel the massive invading fleet. And they aren’t even her toughest adversary.

There are a lot of disparate elements across the series, yet Gischler melds them together into a coherent whole, rather than feeling like he’s simply plugging in fantasy tropes. I was particularly impressed by how even minor characters feel well-developed, such as Mee Hra’Lito. She didn’t need to be in the book at all, being simply the force behind the big bad (or more accurately, the secondary big bad). Yet seeing her motivations, adds depth to proceedings and enhances the epic scope. On the other hand, perhaps the series’s main weakness is lacking a truly central character. Is this Rina’s story? Alem’s? Maurizan’s? The answer is both all of the above, and none of them.

Still, this is the first true series I’ve completed since beginning book reviews on the site, and I’ve certainly enjoyed the experience. Gischler hinted at further volumes in February, saying of his universe, “I feel there’s more there to be mined,” and I wouldn’t mind in the slightest – even if Rina’s role would need… let’s say “serious revision”, based on how this ends, and leave it at that. Or a Peter Jackson trilogy of films based on these: that’d do, just as well.

Author: Victor Gischler

Publisher: 47North, available in both printed and e-book versions, as folllows:

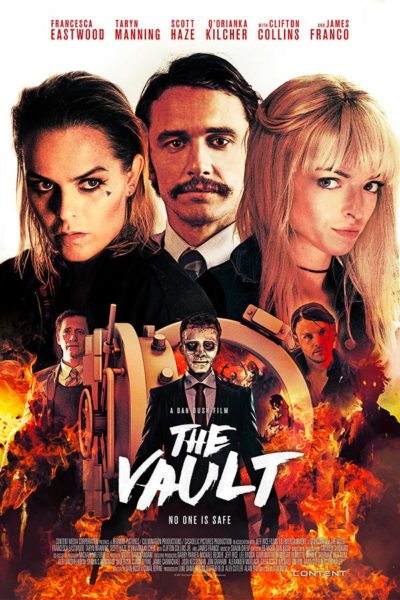

The Vault

★★★

“It’s always somebody else’s vault…”

In an effort to pay off gambling debts their brother Michael (Haze) has run up, sisters Leah (Eastwood) and Vee (Manning) plan and execute a bank robbery. While smart in intent – they set up a diversion, and have a cunning escape route prepared – it’s not long before the operation goes wrong. The bank’s safe does not hold anywhere near the expected haul: fortunately, the assistant manager (Franco) helpfully informs them of an undisclosed vault in the basement holding six million dollars in cash. Sending some of their gang down to the vault, The sisters can only watch on CCTV aghast, as the men are picked off by mysterious figures. For, it turns out, the bank was the site of a robbery in 1982, leading to a hostage situation that ended in multiple deaths. The ghosts of those involved are still in the basement, and opening the vault has apparently released them to take revenge.

In an effort to pay off gambling debts their brother Michael (Haze) has run up, sisters Leah (Eastwood) and Vee (Manning) plan and execute a bank robbery. While smart in intent – they set up a diversion, and have a cunning escape route prepared – it’s not long before the operation goes wrong. The bank’s safe does not hold anywhere near the expected haul: fortunately, the assistant manager (Franco) helpfully informs them of an undisclosed vault in the basement holding six million dollars in cash. Sending some of their gang down to the vault, The sisters can only watch on CCTV aghast, as the men are picked off by mysterious figures. For, it turns out, the bank was the site of a robbery in 1982, leading to a hostage situation that ended in multiple deaths. The ghosts of those involved are still in the basement, and opening the vault has apparently released them to take revenge.

I don’t think I’ve seen a film which combined a heist flick with a ghost story before, and it works fairly well. I say “fairly”, since it feels uneven. The bank robbery side is meticulously assembled, to the point that it could have been better if that been the movie’s sole focus. Eastwood, who made a strong impression in M.F.A., is equally as good here, playing Leah as a cunning strategist who has put a lot of thought into her meticulous plan, only for it to be derailed by factors outside her control. Vee, on the other hand, is a loose cannon, driven by her emotions, and reacting to events rather than managing them. You understand perfectly why the two sisters have led separate lives prior to reuniting to help Michael, though the specific details of the estrangement are never revealed.

It was almost an annoyance when the supernatural elements began to kick in, for those were not handled as effectively. Perhaps it’s a case of over-familiarity, with the horror genre being one with which I am particularly well-acquainted; the barely-glimpsed dark figures just didn’t do it for me. Some elements reminded me of the dumber excesses of the genre too. For instance, the willingness of the robbers to stumble around an extremely dimly-lit basement, without going, “Hang on… This makes no sense”. Or given the spectacular and murderous nature of the original robbery, it stretches belief that these local robbers had apparently never even heard of it. That’s a bit like someone from Hollywood not having heard of Charlie Manson.

While never derailing entirely the solid foundation of character and story-line set up in the first half, I couldn’t help but feel slightly disappointed by the relative weakness of the second portion. Matters are likely not helped by an unsubtle coda which appears to have strayed in from a far worse film. This adds little if anything to the movie, and isn’t the sort of final impression you’d want to leave on an audience. The performances definitely deserved better.

Dir: Dan Bush

Star: Francesca Eastwood, Taryn Manning, Scott Haze, James Franco

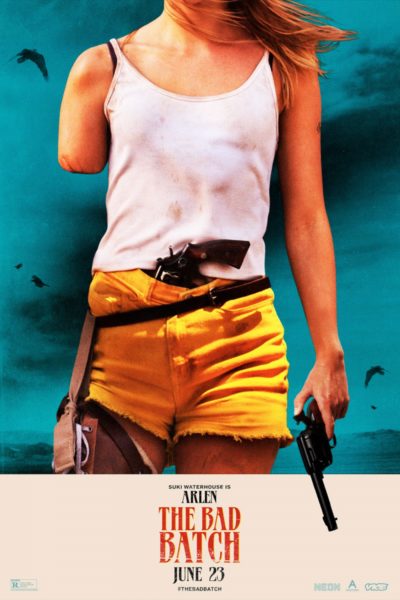

The Bad Batch

★★

“After the apocalypse, there will still be photocopiers. And raves.”

In the film’s defense, it’s not clear quite how post-apocalyptic this is meant to be, since we don’t see anything of the world at large. Everything takes place inside a stretch of desert which has been used, apparently for some time, as a dumping ground for the dregs of society. Into this environment is dropped Arlen (Waterhouse), who soon gets first-hand experience of the situation, when a cannibal mother and daughter capture her, and cut off an arm and a leg. She escapes, and is found and rescued by the Hermit (Carrey), who brings her to Comfort, the nearest the zone offers to civilization. When she’s well again, Arlen returns to take revenge on the mother, but believing the daughter to be innocent, takes her back to Comfort. Which provokes the ire of Miami Man (Monoa), a tattooed behemoth who turns out to be the girl’s father, and wants her back.

In the film’s defense, it’s not clear quite how post-apocalyptic this is meant to be, since we don’t see anything of the world at large. Everything takes place inside a stretch of desert which has been used, apparently for some time, as a dumping ground for the dregs of society. Into this environment is dropped Arlen (Waterhouse), who soon gets first-hand experience of the situation, when a cannibal mother and daughter capture her, and cut off an arm and a leg. She escapes, and is found and rescued by the Hermit (Carrey), who brings her to Comfort, the nearest the zone offers to civilization. When she’s well again, Arlen returns to take revenge on the mother, but believing the daughter to be innocent, takes her back to Comfort. Which provokes the ire of Miami Man (Monoa), a tattooed behemoth who turns out to be the girl’s father, and wants her back.

There’s also Keanu Reeves, running around as “the Dream,” a rave promoter, drug pusher and overall lord of Comfort, who has a harem of pregnant, gun-toting women, all sporting “The Dream is inside me” T-shirts: probably the film’s most memorable image, despite its undoubted ludicrousness. But it all fails to gel into anything coherent or interesting, except in very sporadic moments. It’s a long slog through the first 30 minutes, which are almost entirely dialogue-free, to get to what passes for the meat of the story – though it’s more like undercooked tofu, to be honest.

For the movie never achieves anything like a consistent direction or even tone. Even its Wikipedia page calls the film a “romantic drama horror-thriller”. Good luck juggling all those genres. Is it aspiring to be Mad Max? A spaghetti Western? My best guess could well be, merely a six million dollar budgeted excuse for the director’s favourite Spotify playlist, the soundtrack roaming with jarring inconsistency from Culture Club to Die Antwoord, while we endure lengthy shots of Arlen wandering the desert, high on the Dream’s product. And don’t even get me started on the Hawaiian Momoa playing a supposed Cuban, with a cod-Mexican accent. I’m just glad Chris (whose family is genuinely Cuban) wasn’t around, or all Momoa’s scenes would have been overdubbed with a stream of her derisive snorts, emanating from next to me on the couch.

I did appreciate the look of the film, with some striking imagery: the towering wall of shipping containers, parked in the middle of the desert, for example. That just isn’t enough to sustain a 115-minute running-time, especially when the film seems to get bored of its own ideas, and forget about them. Miami Man, for example, despite proclaiming that his daughter is the only thing he cares about, apparently abandons this search and drifts away from the picture, apparently preferring to do something else for much of the second half. This viewer’s interest was right there beside him.

Dir: Ana Lily Amirpour

Star: Suki Waterhouse, Jason Momoa, Keanu Reeves, Jim Carrey