Tag: Russia

Maria Bochkareva and the Women’s Battalions of Death

We’ve previously written about the Soviet Union’s wholehearted embrace of women soldiers in World War II, but it was not the first time Russia had gone to the female well in defense of their nation. Almost a century ago, while the country was going through a turbulent transition out of Tsarism, combat battalions consisting entirely of women were formed, to fight against Germany in the latter stages of the Great War. At a time when women were not quite yet able to vote in Russia – suffrage would come there, later in 1917 – this was still more advanced in terms of equality on the battlefield, than the United States is currently.

We’ve previously written about the Soviet Union’s wholehearted embrace of women soldiers in World War II, but it was not the first time Russia had gone to the female well in defense of their nation. Almost a century ago, while the country was going through a turbulent transition out of Tsarism, combat battalions consisting entirely of women were formed, to fight against Germany in the latter stages of the Great War. At a time when women were not quite yet able to vote in Russia – suffrage would come there, later in 1917 – this was still more advanced in terms of equality on the battlefield, than the United States is currently.

The purpose of the units was initially for morale purposes. The long grind of the trench-warfare which characterized World War I on the Western front is well-known, but the situation was no different in the East, where the Germans and Russians were locked in a lethal stalemate of artillery bombardments, poison gas attacks and futile assaults which gained trivial amounts of territory at horrendous cost. As the government collapsed, the Tsar abdicating in March 1917, army morale went with it. Soldiers no longer answered to their officers, and spent more time fraternizing with the enemy than fighting them. However, many volunteers still wanted to defend their homeland, and these were organized into groups, in the hope of energizing and/or shaming the regular forces into picking up their arms again.

These volunteers were not just male. On the women’s side, the front runner was Maria Bochkareva, who had already been a trail-blazer in the field of female combat. At the outbreak of the war, she had obtained the personal authorization of the Tsar to join the regular army, and served almost three years there, being both wounded and decorated on multiple occasions. However, growing disenchanted with the collapse in discipline, she quit the army, but shortly after requested permission to organize a group of women. Speaking to the Russian Parliament, she said: “You heard of what I have gone through and what I have done as a soldier. Now, how would it do to organize women like me to serve as an example to the army and lead the men into battle?”

There were 2,000 volunteers initially, but Bochkareva’s strict approach to discipline winnowed out 85% of these. Part of her disenchantment with the regular military was that it was now largely run by “soldier’s committees”, with discipline severely restricted, and even mutineers could no longer be executed. She insisted that her battalion had to be committee-free, run on old-school lines, and this caused conflict, both with the military hierarchy and many of her recruits. But she persevered: the women who stayed were shorn of all their feminine fripperies (as shown in the contemporary photos) and given intensive instruction under male trainers and support staff. A month later, led by Bochkareva, the 1st Russian Women’s Battalion of Death were sent to the front, and took part in the Kerensky offensive.

There were 2,000 volunteers initially, but Bochkareva’s strict approach to discipline winnowed out 85% of these. Part of her disenchantment with the regular military was that it was now largely run by “soldier’s committees”, with discipline severely restricted, and even mutineers could no longer be executed. She insisted that her battalion had to be committee-free, run on old-school lines, and this caused conflict, both with the military hierarchy and many of her recruits. But she persevered: the women who stayed were shorn of all their feminine fripperies (as shown in the contemporary photos) and given intensive instruction under male trainers and support staff. A month later, led by Bochkareva, the 1st Russian Women’s Battalion of Death were sent to the front, and took part in the Kerensky offensive.

The women saw action near the town of Smarhon, and accounts indicate they performed well, along with the other “shock troops”, and Russian forces initially were able to gain ground. However, the regular army barely showed up, and the Germans regrouped, taking back the territory and then some. This failure marked the last significant Russian action of the war. Bochkareva was injured once more, and sent back to recuperate. However, if her acts had minimal impact on the soldiers they were intended to inspire, they did help create as many as fifteen other women’s battalions, some evolving from existing units. Most of these did not see the war, but in October, the 1st Petrograd Women’s Battalion did join regular Cossack troops in the defense of the Winter Palace against Bolshevik forces. Though history records, that didn’t end well either.

It was likely a concept too far ahead of its time, and as Russia descended into anarchy and chaos, the struggle to keep the battalions supplied and organized proved an unequal one. For a while, they served in auxiliary roles behind the front lines, but the death knell came on November 30, 1917 when the new Bolshevik government officially dissolved the units. Those who had been members were free to go, but a number stayed in action, fighting on both sides during the looming Russian Civil War. That included Bochkareva. While holding no great love for the Tsar, she was thoroughly unimpressed with the Communist regime, and toured America and the United Kingdom in 1918 soliciting support against them. On her return to Russia, she tried to organize a further women’s unit as part of the White Army, but was captured by the Bolsheviks, and executed by firing squad in May 1920, at the age of thirty.

Yashka: My Life as Peasant, Exile, and Soldier

“Woman is naturally light-hearted. But if she can purge herself for sacrifice, then through a caressing word, a loving heart and an example of heroism she can save the motherland. We are physically weak, but if we be strong morally and spiritually, we will accomplish more than a large force.”

It’s likely Bochkareva would have fallen into the darkness of historical obscurity, a nine days’ wonder from late in the Great War, except for her trip to the West to rally support against the Bolsheviks. While here, she worked with Russian-born writer, Isaac Don Levine, on her autobiography, telling her story to him over 100 hours and three weeks of interviews, which he translated and transcribed. The resulting book is the source for virtually everything we know about her life to that point, though obviously skips its tragic conclusion, in front of a Communist firing-squad. As such, it largely has to be taken on faith, since there’s little or no corroborating evidence available. Occasionally, it does feel stretched, in a /r/thathappened way, with Bochkareva adored and feted to a suspicious degree. But there’s a lot here, too, which has the ring of authenticity – her depictions of the hell which was the trenches, for example, sounds very much like direct experience.

It’s likely Bochkareva would have fallen into the darkness of historical obscurity, a nine days’ wonder from late in the Great War, except for her trip to the West to rally support against the Bolsheviks. While here, she worked with Russian-born writer, Isaac Don Levine, on her autobiography, telling her story to him over 100 hours and three weeks of interviews, which he translated and transcribed. The resulting book is the source for virtually everything we know about her life to that point, though obviously skips its tragic conclusion, in front of a Communist firing-squad. As such, it largely has to be taken on faith, since there’s little or no corroborating evidence available. Occasionally, it does feel stretched, in a /r/thathappened way, with Bochkareva adored and feted to a suspicious degree. But there’s a lot here, too, which has the ring of authenticity – her depictions of the hell which was the trenches, for example, sounds very much like direct experience.

It takes a while to reach that, beginning with her early life as the daughter of a peasant family. Put to work while still only aged eight, she was married at 15, but her first husband was an abusive alcoholic, and she left him. Thereafter, she had jobs ranging from laundry to construction foreman, and allegedly had a narrow escape from a life of prostitution [looking at her pictures, I have to say, that… seems a bit unlikely?]. She also met Yakov Buk, with whom she began a common-law marriage, but he fell foul of the tsar’s secret police and was exiled to Siberia, Maria accompanying him there. After some more implausible adventures – one chapter is titled “Snared by a Libertine Governor”! – war broke out, and according to our heroine, “My heart yearned to be there, in the boiling caldron of war, to be baptized in its fire and scorched in its lava. The spirit of sacrifice took possession of me. My country called me. And an irresistible force from within pulled me.”

Returning to Tomsk, she applied to join the army – while turned down, she made such a good impression on the local commander that he drew up a telegram to the Tsar with his own recommendation. To the surprise of all, the Tsar authorized her enlistment, and this is where the story takes off, offering a glimpse into the front-lines from a very personal perspective. Initially, Bochkareva was eager to see battle: “Were we nervous? Undoubtedly. But it was not the nervousness of cowardice, rather was it the restlessness of young blood. Our hands were steady, our bayonets fixed. We exulted in our adventure.” Bochkareva was injured and also, briefly, captured by Germans, but fought free, according to her account:

We threw ourselves, five hundred strong, at our captors, wrested many of their rifles and bayonets and engaged in a ferocious hand-to-hand combat, just as our men rushed through the torn wire entanglements into the trenches. The confusion was indescribable; the killing merciless. I grasped five hand-grenades that lay near me and threw them at a group of about ten Germans. They must have all been killed. Our entire line across the river was advancing at the same time. The first German line was occupied by our troops and both banks of the Styr were then in our hands. Thus ended my captivity. I was in German hands for a period of only eight hours and amply avenged even this brief stay.

She eventually realized the upper levels of command lacked the same mettle and commitment, resulting in failed offensives. This undercut army morale, and as the civil turbulence within Russia increased, this also reduced the will to win – not helping matters, were German soldiers, crossing the lines bearing brandy. Eventually, Bochkareva grew so disenchanted, she quit the military in May 1917: “I can’t stand this new order of things. The soldiers don’t fight the Germans any more. My object in joining the army was to defend the country. Now, it is impossible to do so. There is nothing left for me, therefore, but to leave.”

She eventually realized the upper levels of command lacked the same mettle and commitment, resulting in failed offensives. This undercut army morale, and as the civil turbulence within Russia increased, this also reduced the will to win – not helping matters, were German soldiers, crossing the lines bearing brandy. Eventually, Bochkareva grew so disenchanted, she quit the military in May 1917: “I can’t stand this new order of things. The soldiers don’t fight the Germans any more. My object in joining the army was to defend the country. Now, it is impossible to do so. There is nothing left for me, therefore, but to leave.”

This retirement was short-lived, because she quickly came up with the idea of the Women’s Battalion of Death, as described above, eventually leading it into battle. She sustained its strict discipline herself, berating offenders: “You are not worth the uniforms you are wearing. This uniform stands for noble sacrifice, for unselfish patriotism, for purity and honor and loyalty. Every one of you is a disgrace to the uniform. Take them off and get out!” She recounts that when she came across one of her girls making love to another soldier, she bayoneted the girl to death – the man, wisely, ran off before suffering the same fate! However, the rest of the army had a laxer approach. Bochkareva and her soldiers became seen as reactionaries, with some even lynched; it eventually became necessary to disband the unit to prevent further casualties.

Bochkareva’s adventures were not over, as she became a messenger for the anti-Bolshevik forces. She was captured by their opponents, on the way back from meeting General Lavr Kornilov, and the account of her near-execution is chilling – not least, in view of its likely eventual occurrence: “We were surrounded and taken toward a slight elevation of ground, and placed in a line with our backs toward the hill. There were corpses behind us, in front of us, to our left, to our right, at our very feet. There were at least a thousand of them. The scene was a horror of horrors. The poisonous odors were choking us. The executioners did not seem to mind it so much. They were used to them.” While she escaped this fate, in part because one of the committee members had been rescued by her earlier in the war, that was it, and she opted to leave the country, going through Siberia to Vladivostok.

It’s an interesting read, offering a unique perspective on the Russian Revolution and war, though at times, it seems we are hearing more of Levine’s voice than Bochkareva, who hardly sounds like the uneducated peasant girl described. On the other hand, his filtering likely ensures events are explained in a way which makes sense for the intended Western audience; this probably helps equally, with regard to the near-century in time which has elapsed. Despite the yawning chasm in era and location between author and reader, this should be perfectly intelligible to the modern citizen. Certainly, Bochkareva comes over as a true heroine: strong-minded, prepared to go to any lengths to achieve her goals, and an irresistible force. Emmeline Pankhurst, doyenne of the suffragette movement, called her the greatest woman of the century, comparing Bochkareva to Joan of Arc. If premature, considering more than four-fifths of the century was in the future at that point, she still deserves to be considered one of its greatest unsung heroines.

Author: Maria Bochkareva, as told to Isaac Don Levine

Publisher: Frederick A. Stokes, 1919 – available, in full and for free, online.

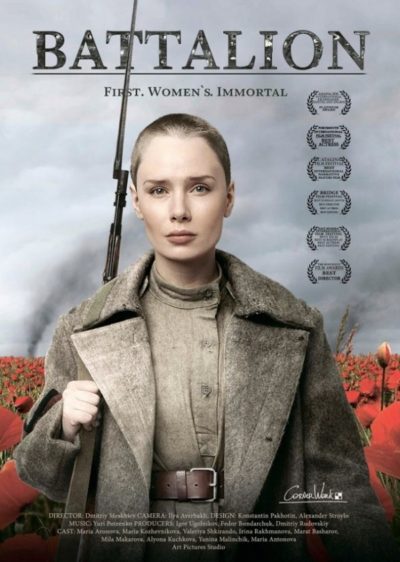

The Battalion

★★★★

“War is hell.”

The above is an equal-opportunity truism and, as we see here, applies just as much to the first matriarchal unit in the modern world. This was the charmingly-named 1st Women’s Battalion of Death, created late in World War I, as the Russian Revolution was taking place. Its aim was to encourage the disillusioned regular army into continuing the fight against Germany, in a “If the ladies are fighting, surely you should be, too?” kinda way. At least initially, it’s the story of two sisters, Nadya (Kuchkova) and Vera, daughters of a rich family, who volunteer for the unit after Vera’s fiance, Petya, is killed at the front. Their mother sends their maid, Froska (Rahmanova), to try and protect her daughters, as they go through the training that will turn them into soldiers capable of taking on the enemy. The film climaxes with an initially successful, but ultimately futile, offensive – while the women initially gain ground, the regular army’s morale is so broken, they don’t support the push, allowing the Germans to counterattack [this aspect is largely true to history].

The above is an equal-opportunity truism and, as we see here, applies just as much to the first matriarchal unit in the modern world. This was the charmingly-named 1st Women’s Battalion of Death, created late in World War I, as the Russian Revolution was taking place. Its aim was to encourage the disillusioned regular army into continuing the fight against Germany, in a “If the ladies are fighting, surely you should be, too?” kinda way. At least initially, it’s the story of two sisters, Nadya (Kuchkova) and Vera, daughters of a rich family, who volunteer for the unit after Vera’s fiance, Petya, is killed at the front. Their mother sends their maid, Froska (Rahmanova), to try and protect her daughters, as they go through the training that will turn them into soldiers capable of taking on the enemy. The film climaxes with an initially successful, but ultimately futile, offensive – while the women initially gain ground, the regular army’s morale is so broken, they don’t support the push, allowing the Germans to counterattack [this aspect is largely true to history].

|

|

|

However, as the film unfolds, it gradually becomes more about the founder of the battalion, Mariya Bochkareva (Aronova) and her story. That’s perhaps wise – to be honest, it’s kinda hard to tell the rank and file soldiers apart, once they’ve had their heads shaved and are wearing the same uniform! This posed particular problems once battle was joined; on at least one occasion, I was convinced a character had been killed, only for her to pop up again, entirely alive, it having been someone else who bit the bullet. Fortunately, it seems Meshiev is more interested in Bochkareva, and it’s a wise decision thanks to a thoroughly convincing performance by Aronova. If she’s hardly the “girls with guns” archetype in looks, her commanding officer is smart, capable, patriotic and ferociously brave, leading from the front; you can see why she inspires the devotion necessary for the troops to follow her into the hell of trench warfare.

And that hell is appropriately portrayed in all its grim unpleasantness from poison gas [a sequence reminiscent of the end of Fraulein Doktor] through to brutal hand-to-hand combat, where we see the soft heart of a raw rookie is no match for a grizzled veteran’s sheer ruthlessness. It’s an approach which does allow the viewer to read this in several ways: it is commending the courage of those who fight, or condemning its pointlessness? The director made his opinion on this fairly clear. In a press conference promoting the film, when asked whether the events portrayed should be taken “as a feat or as a futility”, he replied, “Why would we give birth to a child if everyone will die anyway?” Oh, those wacky Russians… It may be militaristic propaganda; I’d not argue with that as an assessment. However, I don’t care, when it is as effective and well-made as this, with the cinematography and soundtrack standing out, in addition to the fine central performance.

Dir: Dmitriy Meshiev

Star: Maria Aronova, Mariya Kozhevnikova, Irina Rakhmanova, Alyona Kuchkova

Battle for Sevastopol

★★★

“Russian into battle.”

We wrote previously about Lyudmila Pavlichenko, a.k.a. “Lady Death” one of the many bad-ass Soviet women who helped fight off the Nazis in World War II. So, if you’ve been paying attention, you should already know her story, as a female sniper credited with over three hundred enemy kills before being wounded and forced out of front-line action. She then became a spokesperson for the Russians, globe-trotting to raise funds and elicit overseas support, becoming the first Soviet citizen received at the White House, by then President Franklin Roosevelt, and his wife Eleanor – with whom, if this film is to be believed, Pavlichenko developed a strong friendship.

We wrote previously about Lyudmila Pavlichenko, a.k.a. “Lady Death” one of the many bad-ass Soviet women who helped fight off the Nazis in World War II. So, if you’ve been paying attention, you should already know her story, as a female sniper credited with over three hundred enemy kills before being wounded and forced out of front-line action. She then became a spokesperson for the Russians, globe-trotting to raise funds and elicit overseas support, becoming the first Soviet citizen received at the White House, by then President Franklin Roosevelt, and his wife Eleanor – with whom, if this film is to be believed, Pavlichenko developed a strong friendship.

The movie was a Russian-Ukrainian co-production, which is interesting in itself, given the often strained nature of recent relations between the countries. I guess one of the few things on which they can both agree, is that killing Nazis should be lauded. The results are solid enough, hitting the expected notes and telling a respectful, if somewhat too distant, portrait of a heroic figure. The original Russian title translates as Indestructible, and that seems perhaps more appropriate, as she get blown up, shot, and blown up again, defiantly begging her way back to the front repeatedly. Mokrytskyi is at his best with these large-scale spectacles, unfolding over a soundtrack both period and contemporary; in particular, a sequence during an evacuation by boats is stunningly well-constructed, giving a real sense for the hideous, beautiful chaos of war.

It’s rather less successful at giving us insight into the character of the heroine, as played by Peresild; she’s clearly a strong-willed young woman, but that’s about all you get. There are various semi-romantic interludes, as various of her male comrades are wheeled on and off, yet these seem only to provide pauses before the next burst of (undeniably impressive) mayhem. The structure also leaves a little to be desired, switching back and forth between her wartime exploits, and Pavlichenko’s trip to the United States where she met Mrs. Roosevelt (Blackham). It’s all a little bit fragmented, without much narrative flow, and feels more like a selection of unconnected segments, rather than providing a sense of Lyudmila developing as a character. Perhaps it might work better for an already audience familiar with the backdrop of time and places in which it’s set; my knowledge of the Eastern front and Soviet geography is sketchy, to say the least, and the movie appears to presume a higher level.

This is somewhat disappointing, though some of that is because it makes for a really good trailer (below), and because this has been teasing me from the “to watch” pile for what feels like ages, as I waited for coherent English subtitles to be available. Not to say this is a bad film – far from it – just that Mokrytskyi has a better handle on the explosions than his character. Perhaps he is the Michael Bay of Russian cinema? If so, at least it’s closer to good Michael Bay, e.g. The Rock, than bad Michael Bay (Pearl Harbor).

Dir: Serhiy Mokrytskyi

Star: Yulia Peresild, Joan Blackham, Yevheniy Tsyganov, Vitaliy Linetskiy

Assassin’s Run

★★★

“Killer dance moves.”

Prima ballerina Maya Mason (Skya) has it all: great career, billionaire oil-magnate husband Michael (Slater), loving daughter. But it all comes tumbling down when Michael is assassinated in an apparent coup d’etat of his business empire. The final piece is a set of documents, bearer shares that confer control of the company to whoever has them, and the players behind the predatory takeover bid, think Maya knows where these essential certificates are. She insists she has no clue, but is not believed, and to apply pressure, she is framed for drug trafficking and thrown into jail: not where anywhere wants to be, least of all a classical dancer. Worse is to follow, when they kidnap her daughter, but that’s a step too far, and Maya vows to use her very particular set of skills, skills she has acquired over a long career, to make her a nightmare for the people concerned. Or, if you want the one-word version: ballet-fu.

Prima ballerina Maya Mason (Skya) has it all: great career, billionaire oil-magnate husband Michael (Slater), loving daughter. But it all comes tumbling down when Michael is assassinated in an apparent coup d’etat of his business empire. The final piece is a set of documents, bearer shares that confer control of the company to whoever has them, and the players behind the predatory takeover bid, think Maya knows where these essential certificates are. She insists she has no clue, but is not believed, and to apply pressure, she is framed for drug trafficking and thrown into jail: not where anywhere wants to be, least of all a classical dancer. Worse is to follow, when they kidnap her daughter, but that’s a step too far, and Maya vows to use her very particular set of skills, skills she has acquired over a long career, to make her a nightmare for the people concerned. Or, if you want the one-word version: ballet-fu.

If you came into this expecting anything at all like the cover, you’re in for a surprise, as it is likely the most utterly misleading of all time. Neither Slater nor Hauser are actiony types at all in this; rare though it is for a film to undersell the action heroine element, for our purposes we’re all the happier with the end product! It’s certainly a new style, even if we remember that Michelle Yeoh, for example, learned ballet well before martial arts, beginning at the age of four. It’s a shame it’s not put to significant use until the second half, starting with a prison fight after another inmate decides she wants Maya’s ring. This is finished off with a barrage of spin-kick after spin-kick after spin-kick, and is pretty awesome. There’s also a good brawl in a bathroom, but you’re left wishing for more, since it’s something deserving of greater use, and Skya’s flexibility is awesome. Yes, she can kick behind her head, thanks for asking.

She proves herself somewhat multi-talented here, also co-directing and singing the poignant song over the end credits – Chris decided she wants it played at her funeral, but if we played every song she had decided to use, it would be a three-week event… There are some aspects of the plot that don’t make a great deal of sense – why do the villains bother to frame Maya, when they could just kidnap her and torture the certificates’ location out of her? And, I have to say, her darling little daughter is much more whinily irritating, rather than the “adorable” for which the film is clearly aiming. Some of the other performances come over a little bit “English as a second language” – including Hauser as Maya’s former boyfriend – yet it moves along briskly enough, and Skya sells both the dramatic and physical aspects with enough credibility to make for a decent 90 minutes of fun.

Dir: Robert Crombie + Sofya Skya

Star: Sofya Skya, Christian Slater, Cole Hauser, Angus Macfadyen

a.k.a. White Swan

August Eighth

★★★½

“Kseniya, Warrior Princess.”

Firstly, a quick note on the title here, which is a little odd. The subtitles call it August ’08, which would make more sense, since it’s based on the spat that month between Russia and Georgia over the territory of South Ossetia, which had seceded from Georgia with Russian backing. Fortunately, you don’t need to know much about the murky geopolitical climate, though this is firmly entrenched on the side of the Russian “peacekeepers,” so probably should be be relied upon for accuracy [I note it was banned in the Ukraine]. The heroine is Kseniya (Ivanova), a single mom who packs her son Artyom (Fadeev) off to be with dad, so she can go on a trip with her new boyfriend. Unfortunately, father is a soldier stationed near the border; when things kick off down there, communications with the outside world are all but cut. Kseniya embarks on a perilous mission through the war-torn landscape to retrieve Artyom, with the aid of recon commander Lyoha (Matveev). Artyom, meanwhile, retreats into the fantasy world he has constructed to deal with the trauma, in which he is the hero, CosmoBoy, fighting with the aid of a giant robot against the evil Darklord.

Firstly, a quick note on the title here, which is a little odd. The subtitles call it August ’08, which would make more sense, since it’s based on the spat that month between Russia and Georgia over the territory of South Ossetia, which had seceded from Georgia with Russian backing. Fortunately, you don’t need to know much about the murky geopolitical climate, though this is firmly entrenched on the side of the Russian “peacekeepers,” so probably should be be relied upon for accuracy [I note it was banned in the Ukraine]. The heroine is Kseniya (Ivanova), a single mom who packs her son Artyom (Fadeev) off to be with dad, so she can go on a trip with her new boyfriend. Unfortunately, father is a soldier stationed near the border; when things kick off down there, communications with the outside world are all but cut. Kseniya embarks on a perilous mission through the war-torn landscape to retrieve Artyom, with the aid of recon commander Lyoha (Matveev). Artyom, meanwhile, retreats into the fantasy world he has constructed to deal with the trauma, in which he is the hero, CosmoBoy, fighting with the aid of a giant robot against the evil Darklord.

Fairly epic in scale, this does a particularly good job at depicting the hellish nature of battle, in particular the urban kind, where snipers and other threats potentially lurk in every window. It’s also effective when portraying Kseniya’s devotion to Artyom, and her willingness to take any risk to reach him, albeit driven in part by guilt over the poor initial choice to ship him off. While the CGI initially seems a bit ropey, it makes more sense when you realize it’s a child’s imagination, and the production values are generally high-quality. The film’s weakest section is probably the middle, where Kseniya takes a back seat, literally hanging on to Lyoha’s belt and following him on a mission to rescue refugees trapped by the conflict (like I said, “peacekeepers”…), I’d rather have seen her continue as the courageous and self-dependent woman she is, both in the early going, and during the rousing finale, as she makes her way through what’s described as the most dangerous three miles in the world.

Still, even when the movie forgets its action heroine tendencies, it’s a solid piece of war cinema, that easily sustains its 132 minute running-time. Currently available on Netflix, this is the kind of unexpected find that makes having the service worthwhile. For I’d almost certainly have missed it otherwise, and that would have been a shame, since the performances and overall quality are generally more than up to Western standards.

Dir: Dzhanik Fayziev

Star: Svetlana Ivanova, Maksim Matveev, Artyom Fadeev, Aleksey Guskov

Russian World War II Girls With Guns

“If a young Soviet woman patriot is burning to master the machine gun, we should give her the opportunity to realize her dream. If a young Soviet woman wants to become a sniper, we should not discourage her desires.”

— Pravda, 1942

Despite numerous steps towards equality in the past century, there remains only one military theater which has seen large numbers of female soldiers take part, in many areas on an equal footing with their male counterparts. This took place in World War II, on the front between the Nazis and Soviet forces in Eastern Europe, where it’s estimated that more than three-quarters of a million women served on the Russian side. Around 200,000 were decorated for their efforts, with 89 receiving the highest honour, being awarded the Hero of the Soviet Union. It was not so much a philosophical choice by those in charge, as much as one necessitated by expediency.

When the Germans first attacked in 1941, women who attempted to volunteer were turned down, but the Russian forces suffered such a hellacious level of losses that any such restrictions were soon loosened. This echoed a similar situation which had occurred in the later stages of the First World War. After the Russian Revolution got under way in early 1917, fifteen women’s formations were created, such as the charmingly-named “1st Russian Women’s Battalion of Death”. During the Kerensky Offensive, they went over the top into enemy territory when their war-weary male counterparts were reluctant to do so, capturing at least temporarily, a swathe of enemy territory, and were praised for their courage. However, they faced increasing hostility from the men, and the battalions were dissolved after less than a year.

25 years later, women were in particular used as snipers and pilots, but served across virtually the entire range of military fields, including as machine gunners, tank drivers, medics, communication personnel, and on anti-aircraft batteries. There is an issue in terms of verifiable historical data: most of the evidence for and reports on these soldiers, comes solely from the Soviet side. It’s not cynical to think the stories may quite possibly have been exaggerated or fabricated, to varying extents, in the interests of wartime propaganda. However, for the purposes of the rest of this article, we won’t bother trying to separate the legend from the facts: after all, the former are likely to be far more entertaining! So let’s take a look at some of the most-renowned women soldiers to take up arms against the Third Reich on the Russian front.

Snipers

The Russians found women to be particularly suited to the job of sniper: the traits required Major General Morozov, “the father of the sniper movement”, was quoted as saying that “a woman’s hand is more sensitive than is a man’s. Therefore when a woman is shooting, her index finger pulls the trigger more smoothly and purposefully”. By 1943, there were over two thousand female snipers in the military, with more than 12,000 confirmed kills between them. The photo on the right, taken in Germany in May 945, shows a dozen members of the 3rd Shock Army, 1st Belorussian Front, who racked up 775 kills between them, led by Guard Lieutenant VI Artamonov – second row down, second from the right, who had 89. But that tally pales beside the queen of all Soviet sharpshooters.

The Russians found women to be particularly suited to the job of sniper: the traits required Major General Morozov, “the father of the sniper movement”, was quoted as saying that “a woman’s hand is more sensitive than is a man’s. Therefore when a woman is shooting, her index finger pulls the trigger more smoothly and purposefully”. By 1943, there were over two thousand female snipers in the military, with more than 12,000 confirmed kills between them. The photo on the right, taken in Germany in May 945, shows a dozen members of the 3rd Shock Army, 1st Belorussian Front, who racked up 775 kills between them, led by Guard Lieutenant VI Artamonov – second row down, second from the right, who had 89. But that tally pales beside the queen of all Soviet sharpshooters.

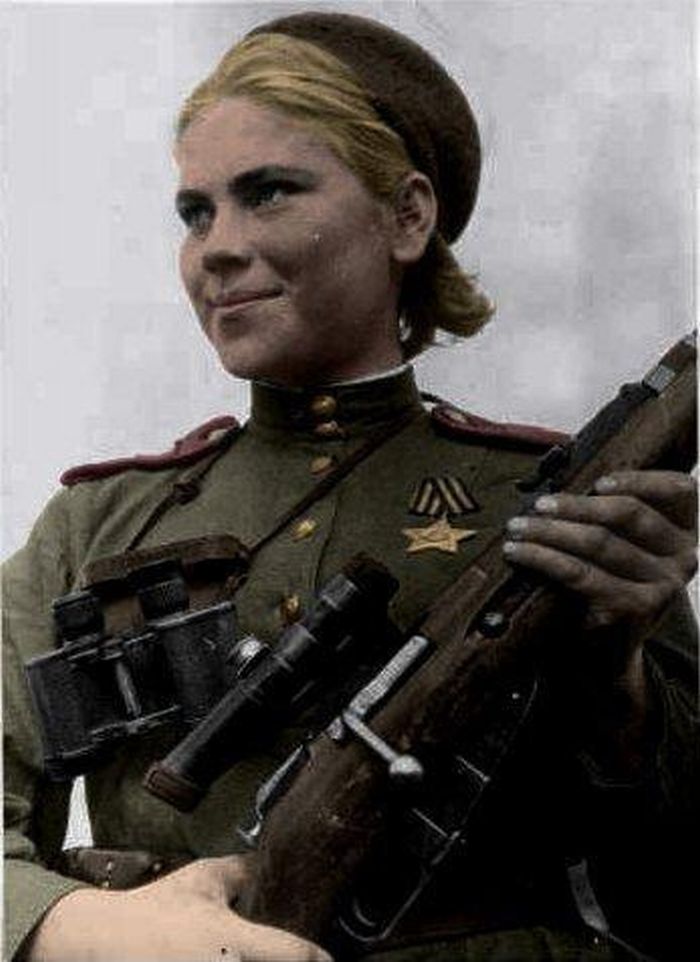

Lyudmila Pavlichenko

“I wear my uniform with honor. It has the Order of Lenin on it. It has been covered with blood in battle. It is plain to see that with American women what is important is whether they wear silk underwear under their uniforms. What the uniform stands for, they have yet to learn.”

— Pavlichenko

Pavlichenko was credited with 309 confirmed kills. Let’s put that into perspective. In all of Kill Bill, the Bride killed only 70 people, less than one-quarter of those who fell victim to Pavlichenko. Even Chris Kyle, the hero of American Sniper, barely reached half her tally, using far more advanced weaponry. And her count may be low. A skeptical Red Army unit insist she proved her prowess, pointing her at two Romanians working with the Germans. When she took them down, she was accepted, but didn’t include them in her official tally, “because they were test shots.” But when she entered actual battle conditions, she froze, until the young soldier next to her was killed. The incident shocked her into action, and she took out two German scouts that same day.

A hundred of her subsequent victims were Nazi officers, and another 36 were snipers working for the other side, taken out in lengthy battles that could last as long as three days and required her to stay in one spot without moving for up to 20 hours. Wounded four times, she was eventually withdrawn from the front, becoming instead a trainer of other snipers and also going on morale-boosting and political trips. These included a 1942 sojourn to America and the United Kingdom, where she became the first Soviet citizen to be officially welcomed at the White House. Unlike many of her colleagues, she made it through the war alive, and after hostilities ended, finished her education and took up a position as a research assistant at the Soviet Navy’s headquarters. She died in 1974, at the age of 58.

Folk singer Woody Guthrie wrote a song inspired by her: “In the mountains and canyons, quiet as the deer/Down in the forest knowing no fear/Lift up your sight, down comes a Hun/Three hundred Nazis fell by your gun.” And in February this year, a film inspired by Pavlichenko’s life was released. The Russian-Ukrainian co-production was called Battle for Sevastopol in Russia, and Indestructible in the Ukraine, and was filmed just before relations between the two countries went south. According to reports, “As played by Yulia Peresild, the film’s heroine is unsmiling and unremittingly tough. “War’s no place for cowards,” she says. She vows to “kill 100 enemies”, hugging her rifle, and upbraids a fellow sniper for firing a shot to finish off a Nazi dying in agony. “They don’t deserve an easy death,” she says.” Here’s the trailer; no subs, but it’s one for which we’ll certainly keep an eye out.

Nina Alexeyevna Lobkovskaya

Nina’s willingness to join the army became a burning desire after her father, a machine-gunner was killed fighting the Germans. She wrote in her memoirs, “Hatred for the enemy that was causing so much human suffering choked me. That hatred cemented my resolution to join the army.” Initially serving as a nurse, in October of 1942, the 17-year-old girl was accepted into the women’s sniper school, near Moscow, along with almost three hundred others. After nine months of training, she was sent to the Kalinin front, and was soon achieving renown for her skills, a regimental newspaper writing, “Nina Lobkovskaya has a sharp eye and steady hand. Her rifle never misses.” In 1944, Lobkovskaya was wounded, but ran away from hospital to rejoin her unit and continue fighting. She was still only 20 by the time the war had ended, but was credited with 89 kills.

Roza Yegorovna Shanina

Roza Yegorovna Shanina

If there was a pin-up girl for Soviet snipers, Shanina (shown atop this article) would probably be it. Though her tally – a “mere” 59 confirmed victims – was not among the highest, her character and heroic character have resonated through the subsequent decades. Her strong personality was apparent well before the war: at age 14, she walked 120 miles to study at college, against the wishes of her parents. After her brother was killed in action in December 1941,. she asked to join the military, but she was not accepted until June 1943. She graduated with honours, and joined the 184th Rifle Division the following April, being appointed commander of a female sniper group. Barely two weeks later, she was awarded her first military decoration, the Order of Glory 3rd Class, having taken out 13 members of the enemy while under fire.

Even after her platoon was disbanded and snipers were withdrawn, Roza persisted: when her request to be returned to the front was refused, she went anyway [she was reprimanded, but avoided formal sanction] Her renown even reached the West, including her photo in the Washingtom Times-Herald and an AP report in September 1944 describing her as “the unseen terror of East Prussia”, citing a Red Army report describing how she sniped five Nazis in a single incident. Shanina was wounded in the shoulder by enemy fire in December, but persisted in efforts to obtain official sanction for service at the front. She finally obtained it on January 8, 1945, but wouldn’t survive the month. While shielding an injured officer, Roza was hit by a shell fragment, and died the following day. She was about two months shy of turning 21.

However, Shanina had – in disregard of regulations – kept a diary over the last few months of her life. This record of her war, along with a large number of letters she had written to friends and relations, were published in the mid-sixties and rekindled interest in this Soviet heroine.

Pilots

The air was another field of war where women could take part on an almost equal footing with men, physical strength not being a major requirement. Indeed, even before war broke out, Russia had the likes of Marina Raskova, who had become a navigator in the Air Force as early as 1933, and was the first woman to teach at the Zhukovskii Air Academy. After the war started, Raskova convinced Joseph Stalin to form three combat groups for women – not just women pilots, but also with female ground support personnel. From 1942 through the war’s end, they flew over thirty thousand combat missions, with over thirty members becoming Heroes of the Soviet Union. That included Raskova herself, who commanded one of the units, the 125th Guards Bomber Aviation Regiment, until her death in a plane crash.

The “Night Witches”

“We bombed, we killed; it was all a part of war. We had an enemy in front of us, and we had to prove that we were stronger and more prepared.”

— Nadezhda Popova

Nachthexen was the perjorative nickname given by the Germans to the 588th Night Bomber Regiment. This was the result of their tactic of switching off their engines in order to glide up unheard and deliver their payload on the target, with the noise of the wind whistling in their wings supposedly like the sound of witches’ broomsticks! The group had to rely on stealth tactics, as their planes were slow and outdated Polikarpov Po-2’s, intended for us as training craft and crop-dusting. However, their very slowness gave them a tactical advantage, as they could fly at speeds of less than 100 mph, where enemy planes like the Messerschmitt Bf 109 would stall out and fall from the sky.

The main tactic used was to fly in groups of three: two would operate as decoys, drawing the fire of anti-aircraft guns, while the third made its bombing pass. It would then swap places with one of the decoys, until all the planes had delivered their lethal cargo. They were so accurate, the Germans spread rumours that the women pilots had been injected with drugs to give them cat-like night vision. But their stamina was equally tested: the limited capacity of the planes often forced them to fly fifteen or more sorties per night, often under heavy fire. Their craft had no radios, no radar, and the pilots didn’t bother with parachutes, because the low altitude at which they operated would have rendered them useless.

One such pilot was Nadezhda Popova, who was born in the Ukraine, and whose life was changed one day when a plane landed near her home. She said, “I had thought only gods could fly. It was amazing to me that a simple man could get in a plane and fly away.” Nadezhda secretly signed up at a gliding school as a 15-year-old, and made her first solo flight and parachute jump the following year. Popova joined up, having lost both her brother and the family home to the war and flew a total of 852 missions, including on one occasion, eighteen in a night. She was shot down multiple times, but always survived, and had numerous other close brushes with death. After one mission, she counted 42 bullet holes in her plane and told her navigator, “Katya, my dear – we will live long.” She wasn’t wrong: Popova made it through the war and for almost seven decades after, dying only a couple of years ago, at the age of 92.

There was, at one point, plans for an Anglo-Canadian-Russian co-production inspired by the squadron, starring Malcolm McDowell, Anna Friel and Sophie Marceau, to be directed by Alexander Siddig, but funding for that fell through. Below, is a documentary (in six parts) on the Night Witches, along with a special bonus, the 1981 Russian feature, В небе ночные ведьмы (Night Witches In The Sky). The former has subs; the latter, unfortunately, doesn’t but still shows you the kind of planes they were flying. It was directed by Evgenia Zhigulenko, one of the members of the 588th, who was awarded the Hero of the Soviet Union decoration for her exploits, so one imagines it’s likely to be fairly accurate.

Lydia Litvyak and Yekaterina Budanova

The term “ace” in regard to fighter pilots is not a vague term: it means someone who has achieved five or more confirmed takedowns of enemy planes. Litvyak and Budanova are the only female fighter aces in the history of flight. Litvyak had 12 solo kills (plus 2 or 4 shared, depending on the source), while Budanova had 11 air victories, six as an individual and five shared; for a while, they were comrades as part of the 586th Fighter Regiment. Litvyak, known as the “White Lily of Stalingrad”, allegedly after the flower painted on the side of her fuselage. When war broke out, she was already a flight instructor, but didn’t have the necessary experience to enlist and become a fighter pilot. So she cooked the books, adding 100 hours on to her logged time, and was accepted.

She shot down her first two victims on September 13, 1942. The second was a German ace himself, with 11 kills, Erwin Maier. After being captured, Maier asked to meet the pilot responsible: when introduced to Litvyak, he thought it was some kind of joke, until she described their dog-fight in detail. She always had a rebellious streak, and on returning from successful missions, would engage in aerobatics over the base, knowing that it irritated her commanding officer. But she had a feminine side as well, and seems to have been in a relationship with fellow ace Alexei Solomatin. When he was killed, she wrote to her mother, “He was not my type, but his insistence and his love for me convinced me to love him”. Litvyak’s fate remains uncertain: she’s generally regarded to have been shot down and killed during a vicious air-battle in August 1943, but some speculate she survived the landing, was captured by the Germans, and moved to Switzerland after the war. Presuming the former, she was posthumously awarded Hero of the Soviet Union by Mikhail Gorbachev in 1990.

She shot down her first two victims on September 13, 1942. The second was a German ace himself, with 11 kills, Erwin Maier. After being captured, Maier asked to meet the pilot responsible: when introduced to Litvyak, he thought it was some kind of joke, until she described their dog-fight in detail. She always had a rebellious streak, and on returning from successful missions, would engage in aerobatics over the base, knowing that it irritated her commanding officer. But she had a feminine side as well, and seems to have been in a relationship with fellow ace Alexei Solomatin. When he was killed, she wrote to her mother, “He was not my type, but his insistence and his love for me convinced me to love him”. Litvyak’s fate remains uncertain: she’s generally regarded to have been shot down and killed during a vicious air-battle in August 1943, but some speculate she survived the landing, was captured by the Germans, and moved to Switzerland after the war. Presuming the former, she was posthumously awarded Hero of the Soviet Union by Mikhail Gorbachev in 1990.

There’s some suggestion that Budanova may have had more kills than Litvyak. She was a smart young woman, who was top of her class in elementary school, but had to give up her education and help support her family after her father died. A job as a carpenter in an aircraft factory awakened her interest in flying, and she got her pilot’s license at age 18, becoming an instructor three years later. After war with Germany broke out in the summer of 1941, she joined the military and was assigned to the 586th. After proving themselves in air battle, the top pilots from the squadron, including both Budanova and Litvyak, were re-assigned to the 437th IAP, on the banks of the Volga. By the end of 1942, Budanova had been further promoted, to the elite 9th Guards Fighter Regiment, consisting entirely of top pilots. But she would not survive the war: her mechanic, Inna Pasportnikova, gave this account of her final battle:

“She spotted three Messerschmitt going on the attack against a group of bombers. Katia attacked and diverted the enemy. A desperate fight developed in the air. Katia managed to pick up an enemy aircraft in her sight and riddle him with bullets. This was the fifth aircraft she killed personally. Katia’s fighter rapidly soared upward and swooped down on a second enemy aircraft. She “stitched” it with bullets, and the second Messer, streaming black smoke, escaped to the west. But Katia’s red starred fighter had been hit; tongues of flame were already licking at the wings.”

Tank commanders

Aleksandra Samusenko

Originally a private in the infantry, Samusenko won the Order of the Red Star in the Battle of Kursk, the largest tank battle in history, for a fight where she and her T-34 tank defeated three German tiger tanks in an encounter lasting several hours. Later in the war, when her commanding officer was killed, she took over and led her group out of an ambush. She also fought alongside US Army Sergeant Joseph Beyrle, who had escaped from a German POW camp in January 1945, and encountered Samusenko’s group while on the run. Beyrle convinced Samusenko he was legitimate by demonstrating he knew demolitions work, and he became the only American to serve in World War 2 with both the US and Soviet Armies; he helped liberate the POW camp in which he had been held! Unfortunately, there was no such happy ending for Samusenko, who was reportedly crushed to death by another Soviet tank in March 1945. She had reached the rank of Captain.

Originally a private in the infantry, Samusenko won the Order of the Red Star in the Battle of Kursk, the largest tank battle in history, for a fight where she and her T-34 tank defeated three German tiger tanks in an encounter lasting several hours. Later in the war, when her commanding officer was killed, she took over and led her group out of an ambush. She also fought alongside US Army Sergeant Joseph Beyrle, who had escaped from a German POW camp in January 1945, and encountered Samusenko’s group while on the run. Beyrle convinced Samusenko he was legitimate by demonstrating he knew demolitions work, and he became the only American to serve in World War 2 with both the US and Soviet Armies; he helped liberate the POW camp in which he had been held! Unfortunately, there was no such happy ending for Samusenko, who was reportedly crushed to death by another Soviet tank in March 1945. She had reached the rank of Captain.

Mariya Oktyabrskaya

“My husband was killed in action defending the motherland. I want revenge on the fascist dogs for his death and for the death of Soviet people tortured by the fascist barbarians. For this purpose I’ve deposited all my personal savings – 50,000 rubles – to the National Bank in order to build a tank. I kindly ask to name the tank ‘Fighting Girlfriend’ and to send me to the front-line as a driver of said tank.”

So wrote Oktyabrskaya to Stalin in 1943, and the State Defense Committee took her up on the offer, although it was initially seen as no more than a morale-boosting publicity stunt. However, Oktyabrskaya completed the five months training, and when she entered the fray in October that year, her courage and skill proved she was more than propaganda. She developed a fearless reputation, not least for leaping out to repair her tank (which indeed had “Fighting Girlfriend” painted on the side of the barrel, per her request!) after it had been hit and disabled by enemy fire. However, that proved to be her undoing, as during one such mechanical foray, during a January 1944 battle near Vitebsk, she was hit in the head by a shell fragment. While Mariya lingered on for two months, she never regained consciousness, and was posthumously awarded Hero of the Soviet Union in August, at the age of 38.

They also served…

Orphaned at age 11, Nina Onilova was inspired in her chosen military field by seeing the 1934 film Chapaev, which included the character of a woman machine-gunner called Anka. She was originally in the army as a medic, but while tending to the wounded during a battle, she helped a machine-gun post fix their jammed weapon and took over handling it, mowing down the enemy. Recognizing a good thing when they saw it, the crew took her on as their permanent gunner. Shortly after, she was hurt in a mortar blast and spent two months in hospital, until the doctors got tired of her demands to be returned to the front, and released her. Back in action, she single-handedly took out a German tank – without a machine-gun, using Molotov cocktails – earning the Order of the Red Banner and the rank of Sergeant. She was killed during a night battle in February 1942, in which she had already taken out a pair of enemy machine-gun positions and was covering the withdrawal of her fellow soldiers.

A group mention goes to the women of the 1077th Anti-Aircraft Regiment, who were part of the defenses around the city of Stalingrad, which witnessed among the most vicious fighting of the war as the Nazis mounted an effort to take over the city in August 1942. Made up almost entirely of young, local volunteers, barely out of high-school, they were left as the last line of defense against the advancing 16th Panzer Division. With little support, and mostly by dropping their anti-aircraft batteries to the horizontal, the regiment held off the Germans for two days. The official war records indicate they “destroyed or damaged 83 tanks and 15 other vehicles carrying infantry, destroyed or dispersed over three battalions of assault infantry, and shot down 14 aircraft” before eventually being over-run and wiped out.

A group mention goes to the women of the 1077th Anti-Aircraft Regiment, who were part of the defenses around the city of Stalingrad, which witnessed among the most vicious fighting of the war as the Nazis mounted an effort to take over the city in August 1942. Made up almost entirely of young, local volunteers, barely out of high-school, they were left as the last line of defense against the advancing 16th Panzer Division. With little support, and mostly by dropping their anti-aircraft batteries to the horizontal, the regiment held off the Germans for two days. The official war records indicate they “destroyed or damaged 83 tanks and 15 other vehicles carrying infantry, destroyed or dispersed over three battalions of assault infantry, and shot down 14 aircraft” before eventually being over-run and wiped out.

Ekaterina Mikhailova-Demina was the only woman to perform front-line reconnaissance for the Soviet marines during World War II. Like Onilova, she lost her parents early [it appears any Russian remake of Annie would have some spectacularly bad-ass orphans!], and volunteered at age 15, lying about her age to get accepted. Also like Onilova, she initially served as a medic, but found work behind the lines boring, and applied to join the marines. In February 1943, she became part of the 369th Independent Naval Infantry Battalion. August the next year saw her receive her first Order of the Red Banner for an assault where she single-handedly assaulted a fortified German position, taking 14 prisoners. She received a second Red Banner in December, for a Croation mission where three-quarters of her platoon were wiped out. Let’s end on a happy note. Unlike many of the women profiled here, Ekaterina survived the war – and, indeed, is still apparently living today, at age 89. Judging by the picture on the right, taken in 2013, she looks like she would still be happy to kick your ass!

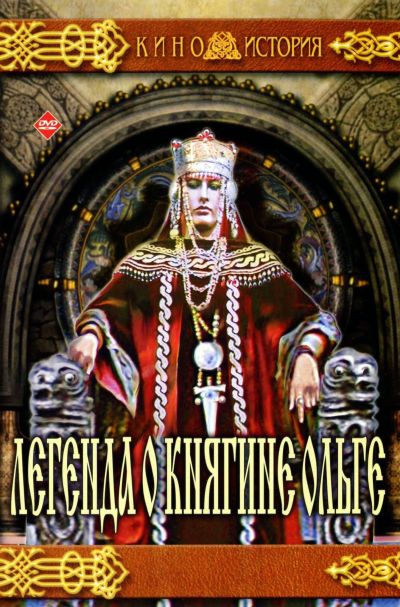

The Legend of Princess Olga

★★

“Olga, Tigress of Siberia”

While the film itself is not that good, it did introduce me to a new action heroine of history: Olga of Kiev, who seems to have been a serious bad-ass, even by the high standards of European bad-asses of the time. There’s some suggestion she was of Viking extraction, with her name originally Helga, and that would certainly make sense. She married Igor of Kiev around 903, and after his death, ruled the state of Kievan Rus’ for 18 years, in the name of her young son, Svyatoslav. The Russian Primary Chronicle recounts how Igor was killed by a neighbouring tribe, the Drevlians, and that’s where things kick off, because they then dispatched a delegation of 20 to pressure Olga into marrying their Prince Mal, so he would become the rule of Kievan Rus’. She had them buried alive, though sent word back that she accepted, only if the Drevlians sent their most distinguished men to accompany her on the journey to their land. Upon their arrival, she offered them a warm welcome and an invitation to clean up after their long journey. After they entered the bathhouse, she locked the doors and set fire to the building.

While the film itself is not that good, it did introduce me to a new action heroine of history: Olga of Kiev, who seems to have been a serious bad-ass, even by the high standards of European bad-asses of the time. There’s some suggestion she was of Viking extraction, with her name originally Helga, and that would certainly make sense. She married Igor of Kiev around 903, and after his death, ruled the state of Kievan Rus’ for 18 years, in the name of her young son, Svyatoslav. The Russian Primary Chronicle recounts how Igor was killed by a neighbouring tribe, the Drevlians, and that’s where things kick off, because they then dispatched a delegation of 20 to pressure Olga into marrying their Prince Mal, so he would become the rule of Kievan Rus’. She had them buried alive, though sent word back that she accepted, only if the Drevlians sent their most distinguished men to accompany her on the journey to their land. Upon their arrival, she offered them a warm welcome and an invitation to clean up after their long journey. After they entered the bathhouse, she locked the doors and set fire to the building.

Having disposed in one stroke of the Drevlian elite, she then invited the unwitting remainder to a funeral feast at the site of her husband’s grave so she could mourn him. That didn’t go quite as the guest planned either: “When the Derevlians were drunk, she bade her followers to fall upon them, and went about herself egging on her retinue to the massacre of the Derevlians. So they cut down five thousand of them; but Olga returned to Kiev and prepared an army to attack the survivors.” First, however, with the aid of some inflammatory pigeons, she set their city on fire. “The people fled from the city, and Olga ordered her soldiers to catch them. Thus she took the city and burned it, and captured the elders of the city. Some of the other captives she killed, while some she gave to others as slaves to her followers. The remnant she left to pay tribute.” She was also the first Rus’ ruler to be converted to Christianity, being baptized by Emperor Constantine VII, and in 1547 was canonized by the Orthodox Church, who proclaimed her “equal to the apostles,” one of only five women so honoured in the history of Christianity.

Hard for any film to portray a woman like that, and to be honest, this one doesn’t succeed. It’s an odd structure which is mostly told in double flashback, from the perspective of Olga’s grandson, Vladimir. On his death-bed, he’s trying to figure out the true nature of his late grandmother (Efimenko), and we then see him as a youth (Ivanov), asking a number of people about her. That includes a Greek scholar who recounts the bloody story above, but also his housekeeper mother, whose memories reveal a different side to Olga. That’s perhaps the film’s most interesting aspect, the problem of separating myth and legend from reality, when everyone has a viewpoint that shows a different aspect of a historical figure. However, the format keeps the film too distant, and I really wish it had focused more on Olga, rather than (the much less-interesting) Vladimir. While made in 1983, it also suffers from an extremely-stilted approach that feels a couple of decades earlier, and despite its potential, certainly falls short of doing its titular subject justice.

Dir: Yuri Ilyenko

Star: Lyudmila Efimenko, Les Serdyuk, Vanya Ivanov, Konstantin Stepankov

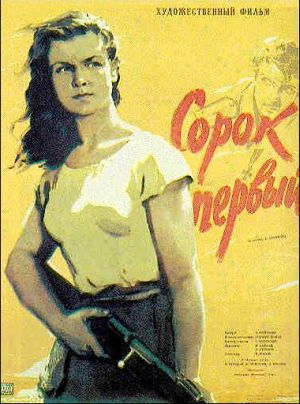

The Forty-First

★★★½

“Robinson Crusoe during wartime.”

It’s the war between the Bolsheviks and the White Guard. A platoon of the former is left with no route of escape except across the desert to the Aral Sea. They begin the perilous trek, under Commander Yevsyukov (Kryuchkov), aided by the unit’s best sniper, Maria Filatovna (Izvitskaya). During the journey, they capture a White officer, Lieutenant Vadim Govorkha (Strizhenov, who looks kinda like Cary Elwes in The Princess Bride!) who is carrying information vital to his side. The Bolsheviks take him with them, as they head back to HQ, with Maria given the task of guarding him. But when she is separated from her comrades, and left with Vadim to fend for themselves after a storm, duty and loyalty to the cause of Communism becomes conflicted with other less revolutionary emotiona.

It’s the war between the Bolsheviks and the White Guard. A platoon of the former is left with no route of escape except across the desert to the Aral Sea. They begin the perilous trek, under Commander Yevsyukov (Kryuchkov), aided by the unit’s best sniper, Maria Filatovna (Izvitskaya). During the journey, they capture a White officer, Lieutenant Vadim Govorkha (Strizhenov, who looks kinda like Cary Elwes in The Princess Bride!) who is carrying information vital to his side. The Bolsheviks take him with them, as they head back to HQ, with Maria given the task of guarding him. But when she is separated from her comrades, and left with Vadim to fend for themselves after a storm, duty and loyalty to the cause of Communism becomes conflicted with other less revolutionary emotiona.

Given this was made in 1957, during the height of the Cold War, with Joe Stalin barely cold in the ground, it’s relatively even-handed, with Govokha portrayed sympathetically, especially given he was The Enemy [his colleague in the White Guards are definitely bastards, as we see when they ruthlessly interrogate an torch a native village in pursuit of the Bolsheviks]. This apparently led to some issue with the censors, who were less impressed. Anyway, Maria is an engaging character, well ahead of her time, and prone to random outbursts of “Fish cholera!” when vexed [look, I’m just reporting that’s what the subtitles say]. She takes surprising glee in gunning down the enemy, keeping count as she does so: Vadim almost becomes kill #41, hence the title. It’s the middle section where she really comes to the fore, taking charge of a difficult situation until the more romantic elements take over.

Even these, which would normally have me rolling my eyes, aren’t too bad, because of the political angle, leading to lines such as “You’re asking me to loll on a feather-bed with you and eat chocolates? When those chocolates are all smeared with blood?” Not your usual romance, shall we say. The ending is just superb: it’s one of those which you absolutely should see coming (it’s foreshadowed enough), but still comes as a surprise. Add in some great settings, both in the desert and by the sea, as well as an interesting visual style and, if this isn’t as action-packed as one might wish, given its era, this remains a surprisingly worthwhile watch.

Dir: Grigori Chukhrai

Star: Izolda Izvitskaya, Oleg Strizhenov, Nikolai Kryuchkov

The Apocalypse Code

★★★½

“Proof that cheerily mindless action pics are not the exclusive domain of Hollywood.”

About ten minutes into this, as another large explosion filled the screen, Chris turned to me and said, “Is this a Michael Bay movie?” While it isn’t, confusion is understandable: this is just the kind of dumb action film for which he is renowned, featuring basic plotting and large-scale mayhem. Terrorist Jaffad is just about to sell four nuclear warheads he has hidden in major cities worldwide back to the Americans, when his entire compound is taken out, at the command of a mysterious figure known as “The Butcher.” FSB Agent Marie (Zavorotnyuk), who had previously been working undercover to get to Jaffad, just manages to escape the slaughter, and is now assigned to track down the Butcher, by getting close to his financial advisor, Louis (Perez). Jaffad gave parts of the eleven-digit code that can be used to detonate the devices, to trusted colleagues in Italy, Norway and Malaysia, and Marie needs to find the code before the Butcher.

About ten minutes into this, as another large explosion filled the screen, Chris turned to me and said, “Is this a Michael Bay movie?” While it isn’t, confusion is understandable: this is just the kind of dumb action film for which he is renowned, featuring basic plotting and large-scale mayhem. Terrorist Jaffad is just about to sell four nuclear warheads he has hidden in major cities worldwide back to the Americans, when his entire compound is taken out, at the command of a mysterious figure known as “The Butcher.” FSB Agent Marie (Zavorotnyuk), who had previously been working undercover to get to Jaffad, just manages to escape the slaughter, and is now assigned to track down the Butcher, by getting close to his financial advisor, Louis (Perez). Jaffad gave parts of the eleven-digit code that can be used to detonate the devices, to trusted colleagues in Italy, Norway and Malaysia, and Marie needs to find the code before the Butcher.

Expensive by Russian standards, yet relatively cheap ($13.5m budget) by American ones, this certainly provides bang for its buck, whizzing around the globe like the Bond movie it mostly wants to be, while putting its heroine in a selection of glamorous costumes and wigs (prefer blondes? Marie can provide for you too, as shown in the pic at lower-right). Shmelev has a good visual eye for proceedings, shooting and framing the action with some beautiful work, and makes the most of his locations. Zavorotnyuk has good screen presence, and I liked that no-one made much mention of her sex; she’s just another agent. It gets bonus points simply through its origins, which confer a different approach – when the Americans show up (though it’s difficult to tell, since everyone speaks Russian), they aren’t particularly good or bad, just there.

However, the plot is not novel at all, the efforts to give Marie backstory are near-laughable, and once the novelty of the Russian heroes wears off, the script has little to offer: significant fragments don’t make much sense, and other scenes seem to be there, just to prove the makers actually went to the locations. Action-wise, it’s somewhat of a mixed bag; it seems pretty clear the lead actress isn’t doing much of the action herself, but there’s a nice fight at the end between Marie and the villain, in front of the console which can be used to detonate the bombs, as a self-destruct timer counts down. You can also enjoy a gun-battle on a boat, and Marie stocking the corridors of a hotel [you’ll understand why I spelled it like that, hohoho].

However, the plot is not novel at all, the efforts to give Marie backstory are near-laughable, and once the novelty of the Russian heroes wears off, the script has little to offer: significant fragments don’t make much sense, and other scenes seem to be there, just to prove the makers actually went to the locations. Action-wise, it’s somewhat of a mixed bag; it seems pretty clear the lead actress isn’t doing much of the action herself, but there’s a nice fight at the end between Marie and the villain, in front of the console which can be used to detonate the bombs, as a self-destruct timer counts down. You can also enjoy a gun-battle on a boat, and Marie stocking the corridors of a hotel [you’ll understand why I spelled it like that, hohoho].

It originally came out in Russia more than three years ago, and I’m a little surprised the film apparently hasn’t had any kind of official release in the UK or US. It’s glossy, well-produced nonsense, that completely fails to engage the brain or heart, yet kept me adequately interested for 105 minutes, with plenty of eye-candy [note to Chris: I mean the exotic locations, darling…] and giant fireballs. While I’ve already forgotten much of what happened in this, it is as good a stab at creating a female Jason Bourne as anything Hollywood has yet managed.

Dir: Vadim Shmelev

Star: Anastasiya Zavorotnyuk, Vincent Perez, Vladimir Menshov, Oskar Kuchera