When I reviewed The Aeronauts earlier this year, I was disappointed to discover that its heroine, Amelia, didn’t exist, being a gender-swapped version of Henry Coxwell. But when I was looking into that, I discovered the existence of Sophie Blanchard, arguably an even more remarkable female pioneer in the world of early flight, who was an undeniable inspiration for the character of Amelia. It’s a shame film-makers opted to invent a made-up person, when Blanchard’s exploits are more than deserving of cinematic treatment.

When I reviewed The Aeronauts earlier this year, I was disappointed to discover that its heroine, Amelia, didn’t exist, being a gender-swapped version of Henry Coxwell. But when I was looking into that, I discovered the existence of Sophie Blanchard, arguably an even more remarkable female pioneer in the world of early flight, who was an undeniable inspiration for the character of Amelia. It’s a shame film-makers opted to invent a made-up person, when Blanchard’s exploits are more than deserving of cinematic treatment.

She was born as Marie Madeleine-Sophie Armant in 1778, at a time when any kind of manned flight had yet to be achieved. But in the following decade, the Montgolfier brothers pioneering efforts helped trigger a continent-wide fascination with balloons and their occupants. Exhibitions and demonstrations proved wildly popular, drawing crowds in the tens of thousands, and setting off crazes for balloon-themed clothing, products and even hairstyles. One such balloonist was Jean-Pierre Blanchard, who had been taking to the air since just a few months after the Montgolfiers launched their debut flight. Among his exploits were the first flight to cross the English Channel and the first in the Americas, in front of President George Washington.

Blanchard had already been married, but abandoned his first wife and their four children for his aerial career. In 1804, he married Ms. Armant, who was not perhaps the kind of person you’d expect to become a daredevil. Her persona was described as being “so nervous that she startled at loud noises and was afraid to ride in horse-drawn carriages.” But she apparently had no such fear of taking her life in her hands. For that was a genuine risk in the early days, with the technology very much untested, and highly explosive hydrogen gas the favoured means of achieving the necessary life. In the event something went wrong, escape options were limited, with parachutes also in their infancy.

Sophie made her first ascent alongside her husband on December 27, 1804, and went solo on only her third flight, the following August in Toulouse. Other women had gone up in balloons before her, but she was the first to pilot her own craft, and become mistress of her own destiny. For Jean-Pierre, her presence alongside him proved helpful. He was not the best of businessmen and had run up considerable debts in the course of his work – this was not a cheap endeavour. The novelty of having a woman co-pilot proved good publicity, and helped draw crowds that were willing to pay for the experience.

For by this point, the novelty of merely seeing someone slowly ascend into the air had worn a bit thin. The Blanchards needed to jazz their spectacle up a bit to keep the crowds coming back. This included letting off fireworks from the balloon – a hazardous practice, given the inflammable nature of both the balloon and its gaseous contents – and tossing dogs out of the basket. Attached to those then recently-invented parachutes, I should add.

For by this point, the novelty of merely seeing someone slowly ascend into the air had worn a bit thin. The Blanchards needed to jazz their spectacle up a bit to keep the crowds coming back. This included letting off fireworks from the balloon – a hazardous practice, given the inflammable nature of both the balloon and its gaseous contents – and tossing dogs out of the basket. Attached to those then recently-invented parachutes, I should add.

They toured Europe for several years, but tragedy struck during an exhibition at The Hague, in the Netherlands, on February 20th, 1808. It wasn’t directly a balloon accident, however. Jean-Pierre suffered a heart attack, and toppled out of the basket, from beside his wife. The resulting fall didn’t kill him immediately, and he lingered on for more than a year, before dying from his injuries in March 1809. Financially, this left Sophie responsible for his debts, and she had to keep flying, to pay off her late husband’s creditors.

Night flights and pyrotechnics were among her specialties and helped get her the attention of none other than the Emperor Napoleon. He had an “official balloonist”, André-Jacques Garnerin, but Garnerin fell out of favour after an ascent to mark Napoleon’s coronation went wrong and turned into an embarrassment to the Emperor. [Garnerin’s niece Élisa, was another pioneering aeronautess, and something of a rival to the subject of this piece]. Blanchard took over the position, and was reportedly named his Chief Air Minister of Ballooning. In that role, she looked into the possibility of invading England by balloon. Fortunately for the British, the prevailing winds across the Channel made the idea unfeasible.

Sophie proved just as popular after Napoleon was deposed, and she was wise enough to play both sides, remaining politically neutral. On the return of King Louis XVIII to the throne in May 1814, she marked his entrance to the French capital with a balloon ascent from the Pont Neuf as part of the celebrations. The new monarch was impressed enough with the spectacle to anoint Sophie the “Official Aeronaut of the Restoration”. By this point, her fame had spread throughout Europe and she travelled the continent, successfully paying off all the debts she had inherited from her husband.

These exhibitions were not without incident. She flew over the Alps, and some of her flights lasted as long as 14½ hours, reaching a height of over 12,000 feet. At that height, the environment was so cold, icicles formed on her face, and she was in danger of passing out due to a lack of oxygen. In 1817, she almost drowned when her selected landing-spot turned out to be a marsh, and she became caught up in her craft’s rigging after touchdown. Only the fortuitous arrival of assistance saved her from a watery grave. However, it was only a stay of execution, rather than a pardon.

These exhibitions were not without incident. She flew over the Alps, and some of her flights lasted as long as 14½ hours, reaching a height of over 12,000 feet. At that height, the environment was so cold, icicles formed on her face, and she was in danger of passing out due to a lack of oxygen. In 1817, she almost drowned when her selected landing-spot turned out to be a marsh, and she became caught up in her craft’s rigging after touchdown. Only the fortuitous arrival of assistance saved her from a watery grave. However, it was only a stay of execution, rather than a pardon.

Blanchard’s luck finally ran out on July 6, 1819, on her 59th recorded flight – an almost identical number to that completed by Jean-Pierre – at the Tivoli Gardens in Paris. Conditions were not ideal, with a strong wind blowing when she took off on a late-evening exhibition. The balloon had attached to it containers of “Bengal fire”, an early pyrotechnic, to enhance the spectacle. Sophie had trouble taking off, and while still on the way up, the balloon and its hydrogen contents caught fire. This was most likely due to contact with a tree knocking some of the Bengal fire out of its vessel, and onto the flammable fabric.

Some spectators initially mistook the conflagration as part of the show, until the craft began to descend rapidly, though its pilot tried to slow the descent by dropping ballast. Initially, this seemed to have worked, and the balloon came down on the roof of a nearby house at a survivable speed. However, Blanchard again was not able to make a clean exit. She was entangled in netting, and when the balloon then fell off the roof, it dragged the pilot with it, crashing to the street below. That secondary descent proved to be a fatal one for Sophie.

A collection was immediately taken up for her children, but on discovering there were none alive(!), the money raised was used to build a memorial (above, right) for her grave in Père Lachaise Cemetery, depicting a burning balloon, which seems a tad callous. Not that I imagine Sophie cared much. On her tombstone is carved “victime de son art et de son intrépidité”, which translates as, “Victim of her art and bravery.”

History has since largely forgotten Blanchard. There was an animated documentary in production about her, The Fantastic Flights of Sophie Blanchard, but there has been little news since the trailer (below) was released, despite a successful Kickstarter campaign in 2013. Otherwise, as The Aeronauts showed, she and the other early woman balloonists such as Élisa Garnerin and Élisabeth Thible, are little more than a historical curiosity. That seems a shame.

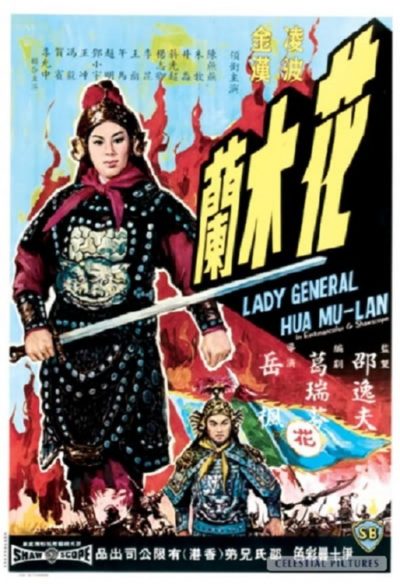

I probably should have done a bit more research before adding this to the list of versions for review here. I saw a sixties movie made by Shaw Brothers with that title, and presumed there would be kung-fu. Boy, was I wrong. There’s about one significant scene, which pits Mulan (Po) and some of her new army colleagues against each other. And that’s it. Oh, there is a battle between Imperial and invading forces. This might have contained some action, but was so poorly photographed – mostly due to incredibly bad lighting – that it was impossible to tell. What there was, instead, was singing.

I probably should have done a bit more research before adding this to the list of versions for review here. I saw a sixties movie made by Shaw Brothers with that title, and presumed there would be kung-fu. Boy, was I wrong. There’s about one significant scene, which pits Mulan (Po) and some of her new army colleagues against each other. And that’s it. Oh, there is a battle between Imperial and invading forces. This might have contained some action, but was so poorly photographed – mostly due to incredibly bad lighting – that it was impossible to tell. What there was, instead, was singing.

I suppose this could be claimed to be a “mockbuster”, not so different from the sound-alike films released by The Asylum, e.g. Snakes on a Train. There’s no doubt this was made to ride the coat-tails of its far larger and better advertised big sister. And it’s not alone, with at least two other Chinese films apparently in production, one animated and the

I suppose this could be claimed to be a “mockbuster”, not so different from the sound-alike films released by The Asylum, e.g. Snakes on a Train. There’s no doubt this was made to ride the coat-tails of its far larger and better advertised big sister. And it’s not alone, with at least two other Chinese films apparently in production, one animated and the  Y’know, considering this is now more than eighty years old, this was likely better than I expected. Chen makes for a solid and engaging heroine, right from the start, when she tricks the residents of a nearby village, who demand she hand over the proceeds of her hunting [I am hoping the dead bird which plummets to the ground with an arrow through it, less than three minutes in, was a stunt avian…]

Y’know, considering this is now more than eighty years old, this was likely better than I expected. Chen makes for a solid and engaging heroine, right from the start, when she tricks the residents of a nearby village, who demand she hand over the proceeds of her hunting [I am hoping the dead bird which plummets to the ground with an arrow through it, less than three minutes in, was a stunt avian…] When I

When I  For by this point, the novelty of merely seeing someone slowly ascend into the air had worn a bit thin. The Blanchards needed to jazz their spectacle up a bit to keep the crowds coming back. This included letting off fireworks from the balloon – a hazardous practice, given the inflammable nature of both the balloon and its gaseous contents – and tossing dogs out of the basket. Attached to those then recently-invented parachutes, I should add.

For by this point, the novelty of merely seeing someone slowly ascend into the air had worn a bit thin. The Blanchards needed to jazz their spectacle up a bit to keep the crowds coming back. This included letting off fireworks from the balloon – a hazardous practice, given the inflammable nature of both the balloon and its gaseous contents – and tossing dogs out of the basket. Attached to those then recently-invented parachutes, I should add. These exhibitions were not without incident. She flew over the Alps, and some of her flights lasted as long as 14½ hours, reaching a height of over 12,000 feet. At that height, the environment was so cold, icicles formed on her face, and she was in danger of passing out due to a lack of oxygen. In 1817, she almost drowned when her selected landing-spot turned out to be a marsh, and she became caught up in her craft’s rigging after touchdown. Only the fortuitous arrival of assistance saved her from a watery grave. However, it was only a stay of execution, rather than a pardon.

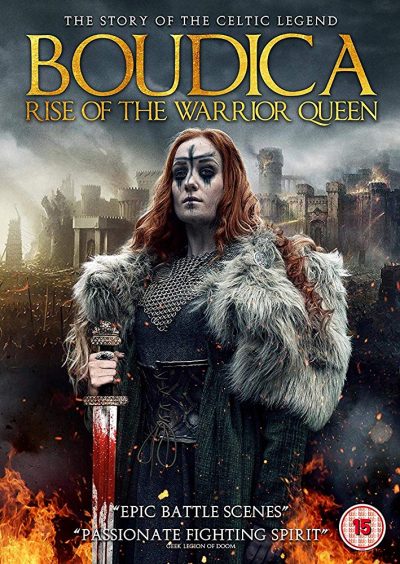

These exhibitions were not without incident. She flew over the Alps, and some of her flights lasted as long as 14½ hours, reaching a height of over 12,000 feet. At that height, the environment was so cold, icicles formed on her face, and she was in danger of passing out due to a lack of oxygen. In 1817, she almost drowned when her selected landing-spot turned out to be a marsh, and she became caught up in her craft’s rigging after touchdown. Only the fortuitous arrival of assistance saved her from a watery grave. However, it was only a stay of execution, rather than a pardon. I try and not let my expectations influence my reviews: a movie deserves to be judged on what it is, rather than what I expected it to be. A film-maker usually doesn’t get to decide, for instance, the DVD sleeve. But when you invoke the name of Boudica in your title, this creates certain requirements with regard to your content, especially when combined with the words “warrior queen.” These are requirements which this movie is utterly incapable of meeting. Technically, the word “rise” is probably the only accurate element to be found, on the cover, which certainly counts as among the most inaccurate in recent memory.

I try and not let my expectations influence my reviews: a movie deserves to be judged on what it is, rather than what I expected it to be. A film-maker usually doesn’t get to decide, for instance, the DVD sleeve. But when you invoke the name of Boudica in your title, this creates certain requirements with regard to your content, especially when combined with the words “warrior queen.” These are requirements which this movie is utterly incapable of meeting. Technically, the word “rise” is probably the only accurate element to be found, on the cover, which certainly counts as among the most inaccurate in recent memory. Not unlike the saga of

Not unlike the saga of

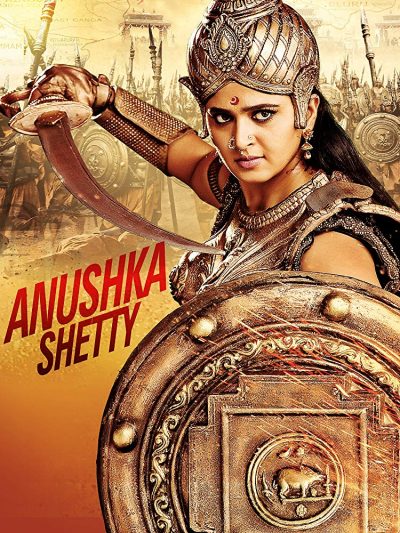

The movie opens with a particularly elaborate disclaimer, admitting that “certain cinematic liberties have been sought,” and that “this film does not claim historical authenticity.” Probably wise: Indians take their national heroes very seriously; just last year, another historical epic, Padmaavat,

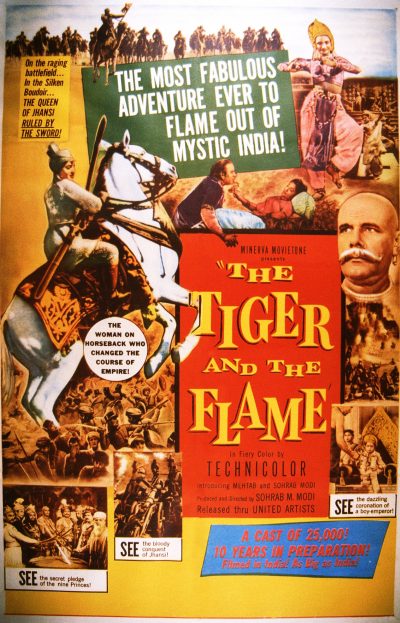

The movie opens with a particularly elaborate disclaimer, admitting that “certain cinematic liberties have been sought,” and that “this film does not claim historical authenticity.” Probably wise: Indians take their national heroes very seriously; just last year, another historical epic, Padmaavat,  Not for the show, I should stress. But as a Brit… Wow, were were really such utter bastards to the Indians when the country was a colony? I was under the impression it was all tea and cricket. But the British, as depicted here, appear largely to be working entirely for the East Indian company, treating the local population with, at best, disdain, and often brutality. All the while, seeking to manipulate local politics (with, it must be said, the help of some Indians) to their own advantage. After 70 episodes of this, such is the guilt, I can barely enjoy my chicken tikka masala without giving it reparations.

Not for the show, I should stress. But as a Brit… Wow, were were really such utter bastards to the Indians when the country was a colony? I was under the impression it was all tea and cricket. But the British, as depicted here, appear largely to be working entirely for the East Indian company, treating the local population with, at best, disdain, and often brutality. All the while, seeking to manipulate local politics (with, it must be said, the help of some Indians) to their own advantage. After 70 episodes of this, such is the guilt, I can barely enjoy my chicken tikka masala without giving it reparations. The British – already unhappy with Manu’s rebellious outbursts – are far from happy at the prospect of her marrying Gangadhar and continuing the line. Even before she arrives at the palace, there are backroom conspiracies involving some of his relatives (not least his own mother), who ally themselves with the colonialists for their mutual benefit. These schemes go up to and include multiple assassination plots against the king, and indeed, his bride-to-be. Time for Kranti Guru to come out again, particularly to face off against gold-toothed British psychopath Marshall (Verma). His relentless pursuit, without regard for who gets hurt, earns him Manu’s undying enmity. [Weirdly, he’s played by an Indian actor in “white face”, as are some – but not all – of the other English officers, some of whom are dubbed.]

The British – already unhappy with Manu’s rebellious outbursts – are far from happy at the prospect of her marrying Gangadhar and continuing the line. Even before she arrives at the palace, there are backroom conspiracies involving some of his relatives (not least his own mother), who ally themselves with the colonialists for their mutual benefit. These schemes go up to and include multiple assassination plots against the king, and indeed, his bride-to-be. Time for Kranti Guru to come out again, particularly to face off against gold-toothed British psychopath Marshall (Verma). His relentless pursuit, without regard for who gets hurt, earns him Manu’s undying enmity. [Weirdly, he’s played by an Indian actor in “white face”, as are some – but not all – of the other English officers, some of whom are dubbed.] For the great majority of the time, it’s light stuff, with Manu escaping every pitfall her enemies set for her. Then, the hammer drops: to extend the GoT comparison, it’s the Rani equivalent of the Red Wedding. Fewer bodies, to be sure – just one – yet the resulting emotional wallop was still brutal, sending me through multiple stages of grief during the subsequent fall-out. “No… Surely they haven’t… It’s got to be a dream sequence.” All told, it was easily the most impactful death in any of the telenovelas I’ve watched, regardless of their origin, and the repercussions ran on for multiple episodes. As do the reaction shots. So. Many. Reaction. Shots.

For the great majority of the time, it’s light stuff, with Manu escaping every pitfall her enemies set for her. Then, the hammer drops: to extend the GoT comparison, it’s the Rani equivalent of the Red Wedding. Fewer bodies, to be sure – just one – yet the resulting emotional wallop was still brutal, sending me through multiple stages of grief during the subsequent fall-out. “No… Surely they haven’t… It’s got to be a dream sequence.” All told, it was easily the most impactful death in any of the telenovelas I’ve watched, regardless of their origin, and the repercussions ran on for multiple episodes. As do the reaction shots. So. Many. Reaction. Shots.