★★★

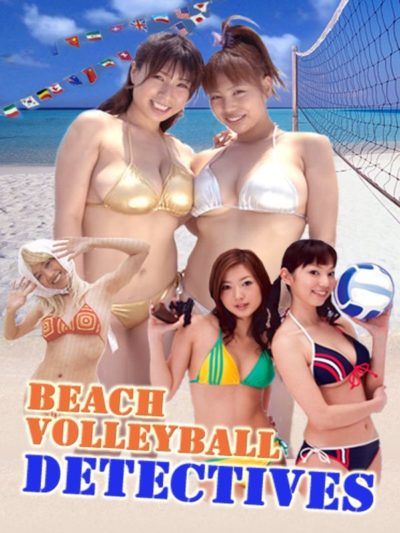

“So, illegal underground beach volleyball matches?”

The above line of dialogue is a perfect litmus test for what you’ll think of this. If your reaction is a derisive snort, this pair of hour-long items – I have qualms about calling them anything as high-minded as “feature films” – is probably not for you. And I cheerfully admit, snorting is probably the default, and understandable, reaction. If, on the other hand, you are giddy with anticipation at the very thought, then I probably cannot recommend it highly enough.

The above line of dialogue is a perfect litmus test for what you’ll think of this. If your reaction is a derisive snort, this pair of hour-long items – I have qualms about calling them anything as high-minded as “feature films” – is probably not for you. And I cheerfully admit, snorting is probably the default, and understandable, reaction. If, on the other hand, you are giddy with anticipation at the very thought, then I probably cannot recommend it highly enough.

It’s one of those cases where the title pretty much explains the basic idea. Three young, photogenic members of the Foreign Affairs Department, led by Haruka, get paired up with Wakana, a equally young and photogenic visiting policewoman from Hawaii, after they discover blueprints for a mini-nuke, capable of wiping out everything in a 100-mile radius. To find those behind the scheme, the four law-enforcement officials have to go undercover at the training camp for an international volleyball tournament, and figure out which of their opponents – Chinese, Russian or Indian – are after the blueprints.

This manages to be incredibly tacky, while also remaining remarkably chaste. There is no actual content here which would be worse than PG-rated. But it’s all shot in a way that resembles Russ Meyer in heat: focusing on the actresses’ erogenous zones, sometimes to the exclusion of everything else in the frame. Which makes sense, considering the director’s filmography includes what I can only presume are far more explicit titles, such as her debut, Chronic Rutting Adultery Wife. And who can forget Miss Peach: Peachy Sweetness Huge Breasts? Meanwhile, the writer is Takao Nakano, who gave the world – and this site – Big Tits Zombie.

It also turns out that, much like the Force and duct-tape, beach volleyball has a light side and a dark side. These are, respectively, White Sand Beach and Black Sand Beach. This mystical philosophy may help explain the superpowers on display here. For instance, the Indian team can levitate, the Russian player can turn into multiple mirror images of herself, and the Japanese and Chinese have a whole slew of super-powered moves, up to and including “Intercontinental Ballistic Missile No. 1”. I should mention, all these different nationalities are played by Japanese ladies, though in deference to her cultural heritage, the “Russian” does wear a headscarf. The Chinese are defined by their frequent spouting of Socialist dogma, such as “Go ahead and vote on it, you silly democratic people.”

The execution is woefully inept, The matches play like a low-rent version of Shaolin Soccer, right down to the ball turning into a dragon, a result of the appropriately named “Dragon Spike” move. Except, here, the CGI might barely have passed muster in the 1980’s. What passes for “combat” is hardly any better, if at all. Yet this incompetence actually becomes part of the trashy charm, and there’s a surprising amount of plot here. Our heroines have to handle not just their enemies, but also betrayal from within, and jealous fights between Haruka and Wakana over the attentions of their coach, with the help of a Yoda-esque monk, Harlequin. It’s all undeniably goofy, yet I was amused and entertained – likely more than I should probably admit…

Dir: Yumi Yoshiyuki

Star: Arisu Kagamino, Sakurako Kaoru, Chihiro Koganezaki, Kaori Nakamura

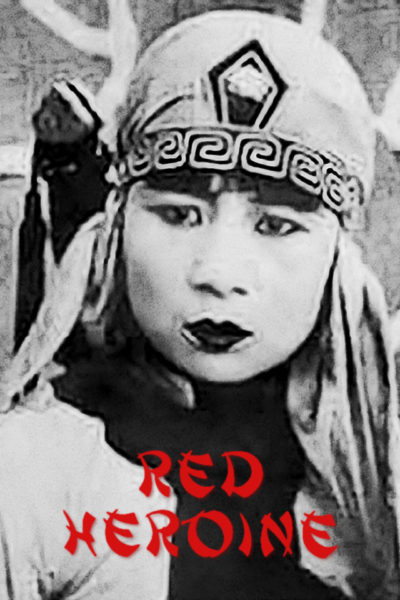

Tied somewhat to our March feature on the earliest action heroines in cinema, is this Chinese film, It’s not just the oldest surviving action heroine film from that country, it’s the oldest martial-arts film of any kind. This silent feature dates from all the way back in 1929 – I had to keep reminding myself that the “red” in the title was not a Communism reference, this being from well before such things. It’s most likely an attempt to cash in on The Burning of the Red Lotus Temple, a now-lost film series whose highly successful release had begun the previous year.

Tied somewhat to our March feature on the earliest action heroines in cinema, is this Chinese film, It’s not just the oldest surviving action heroine film from that country, it’s the oldest martial-arts film of any kind. This silent feature dates from all the way back in 1929 – I had to keep reminding myself that the “red” in the title was not a Communism reference, this being from well before such things. It’s most likely an attempt to cash in on The Burning of the Red Lotus Temple, a now-lost film series whose highly successful release had begun the previous year. “Have you not learned by this time that I am not a weak woman, but a strong one? You have harried me and injured me and wronged me and set tortures for me, but here I stand, unharmed. This day I will have my revenge.”

“Have you not learned by this time that I am not a weak woman, but a strong one? You have harried me and injured me and wronged me and set tortures for me, but here I stand, unharmed. This day I will have my revenge.” The writing style, while enthusiastic, is occasionally odd in that it chooses to skip over what should be thrilling moments. I wonder if perhaps this was the book’s way of not stealing the serial’s thunder? For example, as Kaitlyn sets off, accompanying a big cat her father was shipping to its end buyer, a major incident is all but entirely skipped over thus: “How the lion escaped, how the fearless young woman captured it alone, unaided, may be found in the files of all metropolitan newspapers.” Uh, what? But there are times when MacGrath does hit it out of the park, descriptively: “In the blue of night the temple looked as though it had been sculptured out of mist. Here and there the heavy dews, touched by the moon lances, flung back flames of sapphire, cold and sharp.”

The writing style, while enthusiastic, is occasionally odd in that it chooses to skip over what should be thrilling moments. I wonder if perhaps this was the book’s way of not stealing the serial’s thunder? For example, as Kaitlyn sets off, accompanying a big cat her father was shipping to its end buyer, a major incident is all but entirely skipped over thus: “How the lion escaped, how the fearless young woman captured it alone, unaided, may be found in the files of all metropolitan newspapers.” Uh, what? But there are times when MacGrath does hit it out of the park, descriptively: “In the blue of night the temple looked as though it had been sculptured out of mist. Here and there the heavy dews, touched by the moon lances, flung back flames of sapphire, cold and sharp.”