★★★½

“The Jones’ town massacre.”

A low-key take on the whole Marvel Universe, this takes place alongside the likes of The Avengers, yet almost separate from them. This means there are a couple of references to more high-profile superheroes (the battle for New York depicted in Avengers is called ‘The Incident’), plus nods to, and characters from, Netflix’s other Marvel show, Daredevil. Otherwise, this is its own creature, and likely the better for it. The heroine is Jessica Jones (Ritter, possessing an Eliza Dushku vibe), a private eye who has been gifted – or cursed – with remarkable strength. While this does occasionally come in handy, as we see in the first episode when serving a subpoena to an unwilling recipient, she’s well aware of the downside that her talent might bring; in the comics, but barely discussed in the show, she had a brief stint as a superhero, which ended badly. Now, she largely keeps it to herself, rather than running around the city fighting crime ‘n’ stuff.

A low-key take on the whole Marvel Universe, this takes place alongside the likes of The Avengers, yet almost separate from them. This means there are a couple of references to more high-profile superheroes (the battle for New York depicted in Avengers is called ‘The Incident’), plus nods to, and characters from, Netflix’s other Marvel show, Daredevil. Otherwise, this is its own creature, and likely the better for it. The heroine is Jessica Jones (Ritter, possessing an Eliza Dushku vibe), a private eye who has been gifted – or cursed – with remarkable strength. While this does occasionally come in handy, as we see in the first episode when serving a subpoena to an unwilling recipient, she’s well aware of the downside that her talent might bring; in the comics, but barely discussed in the show, she had a brief stint as a superhero, which ended badly. Now, she largely keeps it to herself, rather than running around the city fighting crime ‘n’ stuff.

Our story starts with her taking on what looks like a mundane missing person job, the parents of the girl in question having been recommended to her PI services. The disappearance turns out to have been engineered by “Kilgrave” (Tennant), the pseudonym adopted by a man with the talent of mind-control. Jessica crossed paths with Kilgrave before, having been one of those under his mental thumb. The experience left Jones with post-traumatic stress, but she believed she had seen the last of him – only to discover that not only is he still alive, he is perhaps even more obsessed with Jessica than he was. Fortunately, she isn’t alone, with help from her foster sister, Trish Walker (Taylor), now a popular radio host, and Luke Cage (Colter), a barman who, like Jones, has an abnormal ability he prefers remain private. However, how can you defeat someone who can take anyone, even your closest friends, and turn them against you as spies or assassins?

Our story starts with her taking on what looks like a mundane missing person job, the parents of the girl in question having been recommended to her PI services. The disappearance turns out to have been engineered by “Kilgrave” (Tennant), the pseudonym adopted by a man with the talent of mind-control. Jessica crossed paths with Kilgrave before, having been one of those under his mental thumb. The experience left Jones with post-traumatic stress, but she believed she had seen the last of him – only to discover that not only is he still alive, he is perhaps even more obsessed with Jessica than he was. Fortunately, she isn’t alone, with help from her foster sister, Trish Walker (Taylor), now a popular radio host, and Luke Cage (Colter), a barman who, like Jones, has an abnormal ability he prefers remain private. However, how can you defeat someone who can take anyone, even your closest friends, and turn them against you as spies or assassins?

If you are used to Marvel movies, this is very much understated in comparison to something like The Avengers or Guardians of the Galaxy, big, bombastic epics with a lot of things blowing up. It’s often easy to forget they share the same universe – but then, remember that “comics” aren’t a genre, they’re a medium. While the term “comic-book movie” has come to mean a certain type of film, the truth is the range actually includes titles as diverse as The History of Violence, The Road to Perdition and When the Wind Blows. It’s possible to imagine a version of Jessica Jones, with its heroine entirely free of all special abilities – you’d more or less have a modern noir, right down to the jazzy intro music and voice-over narration. Kilgrave would be harder, admittedly, since his powers are largely what he has allowed to define him, but perhaps he could become a creepy, stalkery ex-boyfriend.

Jones is certainly flawed, though how many of these flaws are the result of her first encounter with Kilgrave is uncertain, given the limited glimpses we get of her life before that. She now drinks heavily, can’t maintain a relationship with anyone, and is crabby and sarcastic. All told, not a very likeable individual, and this is reflected in the near-lone existence she has. As the audience spends time with her though, they grow to appreciate her better qualities, such as a ferocious loyalty which, once earned, is never lost. She’s relentless too: once she sinks her teeth into a case, you probably would have to cut off Jones’s head to get her to back off, though the pursuit of Kilgrave certainly has a significant personal element to it too. As well as strength, it appears Jessica has the ability to take damage and keep going; not just physical either, but also psychological and spiritual, because she goes through the ringer over the course of these 13 episodes.

However, she may still be overshadowed by Kilgrave, even during the early episodes where he is rarely seen. Unlike most traditional “comic-book” villains, Kilgrave has a philosophy that informs his actions, and even possesses a twisted morality of sorts. He wants, and indeed, is desperate for, Jessica to like him, without being compelled to do so through mind-control. Tennant is quite brilliant in the role: you’ll be astonished if you’ve only seen him in Doctor Who, less so if you’re aware of his excellent work elsewhere, such as in Broadchurch, or even as Hamlet. Kilgrave is a total dick, likely a clinical psychopath, with a short fuse. This may be close to the worst combination possible for someone given the ability to manipulate others like a puppet. However, Tennant manages to retain a good degree of humanity in his depiction of the character. Like many psychopaths, Kilgrave can be charming on occasion, and the differences between him and Jessica are not as obvious as you might think: they are both children of trauma.

Less effective, for me, were the supporting cast, and this aspect left the show short of “Seal of Approval” status [though I know many disagree]. The apparently obligatory, dysfunctional romance between Jones and Cage feels both too sudden and forced: I guess he needed to be established for his own, upcoming TV series, though I’ll probably not bother with it, any more than I did with Daredevil. Meanwhile, Carrie Ann Moss’s aggressive lawyer, oddly gender-swapped from the comic, never served any significant purpose over the course of this first season. More effective is the complex relationship between Jessica and Trish; one born of personal tragedies, on both sides, which still continue to resonate, years later. Still, I couldn’t help feeling that a 13-episode series was over-stretching the material; a few of the shows appeared a good deal more filler than killer, and I suspect a 10-episode order might have been better overall.

Less effective, for me, were the supporting cast, and this aspect left the show short of “Seal of Approval” status [though I know many disagree]. The apparently obligatory, dysfunctional romance between Jones and Cage feels both too sudden and forced: I guess he needed to be established for his own, upcoming TV series, though I’ll probably not bother with it, any more than I did with Daredevil. Meanwhile, Carrie Ann Moss’s aggressive lawyer, oddly gender-swapped from the comic, never served any significant purpose over the course of this first season. More effective is the complex relationship between Jessica and Trish; one born of personal tragedies, on both sides, which still continue to resonate, years later. Still, I couldn’t help feeling that a 13-episode series was over-stretching the material; a few of the shows appeared a good deal more filler than killer, and I suspect a 10-episode order might have been better overall.

The other main weakness, to me, was some contrived plotting, such as the way in which an inexplicable immunity to Kilgrave’s powers becomes an essential part of the final arc. I can’t say if the comics dealt with it similarly, but for a series so grounded in gritty realism, suddenly to pull out something which felt more like a big lump of handwavey Kryptonite, was disappointing. Similarly, the final confrontation between Kilgrave and Jones also had the former behave in a rather dumb way, closer to that of a sixties Bond villain, than the smart and savvy psycho he’d been portrayed as over the previous 12 episodes. I guess you can take the television show out of the comic-book, but you can’t entirely take the comic-book out of the television show. Or something…

Those flaws noted, this is still likely the best action-heroine entry to come out of either Marvel or DC so far. The show has been renewed for a second season, although the time-frame for this is uncertain, and it may end up being queued behind other planned Marvel/Netflix series – not least The Defenders, their “low-rent” version of The Avengers which will team up Daredevil with Jones, Cage and Iron Fist. Additionally, the makers will need to figure out who or what will replace Kilgrave as the show’s “big bad”, a tough act to follow. If the future of Jessica’s day job seems highly uncertain at the end of this run, there are also hints that she is no longer going to be quite the lone wolf operator that she was here, possibly building eventually toward that Defenders team-up. If not as jaw-droppingly good as some claim (“The best show on TV”?), its hard-boiled approach has to be commended, and is refreshingly unlike anything else available, from any source.

Creator: Melissa Rosenberg

Star: Krysten Ritter, Mike Colter, David Tennant, Rachael Taylor

Having been involved in low-budget feature films (on both sides of the camera), I’m very much aware of how much dedication and hard work it takes to bring a feature to the screen. I tend to try and cut them slack where possible, especially when they’re in our genre. Unfortunately, the results here aren’t actually very good, and I struggled to stay focused on the film for much of the running time.

Having been involved in low-budget feature films (on both sides of the camera), I’m very much aware of how much dedication and hard work it takes to bring a feature to the screen. I tend to try and cut them slack where possible, especially when they’re in our genre. Unfortunately, the results here aren’t actually very good, and I struggled to stay focused on the film for much of the running time.

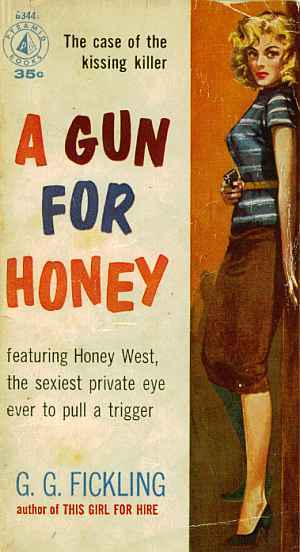

Honey West is best known as the heroine of a mid-60’s TV show created by Aaron Spelling, starring Anne Francis. But her origins actually date back almost a decade further, to a series of pulp detective novels written by Forest Fickling, under the vaguely-pseudonymic name of G.G.Fickling – his wife was Gloria, which may explain the choice. The heroine is a private eye, who follows her father into the profession, after he was killed on the job. These adventures, judging by A Gun for Honey, are rather more hard-boiled, and occasionally risque, than the TV show, though even in the book, the characters never actually seem to do “it”.

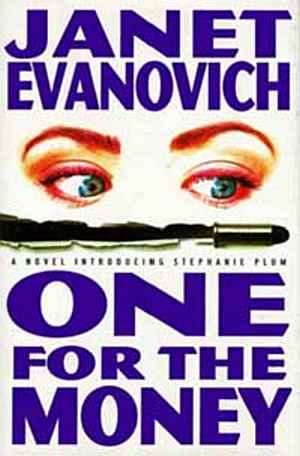

Honey West is best known as the heroine of a mid-60’s TV show created by Aaron Spelling, starring Anne Francis. But her origins actually date back almost a decade further, to a series of pulp detective novels written by Forest Fickling, under the vaguely-pseudonymic name of G.G.Fickling – his wife was Gloria, which may explain the choice. The heroine is a private eye, who follows her father into the profession, after he was killed on the job. These adventures, judging by A Gun for Honey, are rather more hard-boiled, and occasionally risque, than the TV show, though even in the book, the characters never actually seem to do “it”. Former romance writer Evanovich switched genres and hit paydirt immediately with the first in the series, describing the adventures of former Newark lingerie buyer Stephanie Plum. She’s forced, through financial misadventure, to find a new job, and goes for a job filing paperwork for her bail bondsman cousin, but ends up hunting FTA’s (those who Failed To Appear for their court date) instead. She starts at the top, with suspended cop Joe Morelli, who has vanished after being accused of shooting an unarmed man. But as the witnesses to the incident start to die, Plum realises things may not be what they seem. The novice bounty huntress is well out of her depth, not least when she crosses psycho boxer Ramirez – until help comes from an unexpected source…

Former romance writer Evanovich switched genres and hit paydirt immediately with the first in the series, describing the adventures of former Newark lingerie buyer Stephanie Plum. She’s forced, through financial misadventure, to find a new job, and goes for a job filing paperwork for her bail bondsman cousin, but ends up hunting FTA’s (those who Failed To Appear for their court date) instead. She starts at the top, with suspended cop Joe Morelli, who has vanished after being accused of shooting an unarmed man. But as the witnesses to the incident start to die, Plum realises things may not be what they seem. The novice bounty huntress is well out of her depth, not least when she crosses psycho boxer Ramirez – until help comes from an unexpected source…