While there have been box-office bombs in the genre since – Tank Girl, Barb Wire, Catwoman – the epic scale of Cutthroat Island‘s failure surpasses them all. It cost $115 million to make, a sizable amount even now, yet didn’t even crack the top ten in the United States on its opening weekend, finishing behind Dracula: Dead and Loving It. The film barely grossed $10 million in North America, and still regularly appears on lists of the biggest cinematic financial flops, sometimes right at the top. With December marking the 20th anniversary of is release, let’s take a look back at what is perhaps the most infamous action heroine film of all time.

While there have been box-office bombs in the genre since – Tank Girl, Barb Wire, Catwoman – the epic scale of Cutthroat Island‘s failure surpasses them all. It cost $115 million to make, a sizable amount even now, yet didn’t even crack the top ten in the United States on its opening weekend, finishing behind Dracula: Dead and Loving It. The film barely grossed $10 million in North America, and still regularly appears on lists of the biggest cinematic financial flops, sometimes right at the top. With December marking the 20th anniversary of is release, let’s take a look back at what is perhaps the most infamous action heroine film of all time.

Its origins are tied to another ill-fated, woman pirate venture from around that time. Columbia’s equally big-budget saga, Mistress of the Seasm which foundered in the summer of 1993, after director Paul Verhoeven left the project. One of the reported replacements for Verhoeven was Finnish director Renny Harlin, although after he was dumped, and Verhoeven returned, the film’s intended star then jumped ship. That star was Harlin’s then fiancee, Geena Davis, apparently miffed at her other half being courted then rejected by the studio. A source said ”From what I understand, she’s decided she wants to make a movie with her future hubby.” Mario Kassar, the chief of rival studio Carolco, seized the chance to woo both Harlin and Davis for his rival project, which already had Michael Douglas signed on as the male lead and love interest. [Mistress never got made; in the light of subsequent events, that was likely a win for Columbia]

Its origins are tied to another ill-fated, woman pirate venture from around that time. Columbia’s equally big-budget saga, Mistress of the Seasm which foundered in the summer of 1993, after director Paul Verhoeven left the project. One of the reported replacements for Verhoeven was Finnish director Renny Harlin, although after he was dumped, and Verhoeven returned, the film’s intended star then jumped ship. That star was Harlin’s then fiancee, Geena Davis, apparently miffed at her other half being courted then rejected by the studio. A source said ”From what I understand, she’s decided she wants to make a movie with her future hubby.” Mario Kassar, the chief of rival studio Carolco, seized the chance to woo both Harlin and Davis for his rival project, which already had Michael Douglas signed on as the male lead and love interest. [Mistress never got made; in the light of subsequent events, that was likely a win for Columbia]

But Carolco were already in financial trouble, having fallen far from smash-hits such as Terminator 2 and Total Recall. They had restructured in 1992, and sold off shares in 1993, yet were still in such dire cash-flow straits that they could only afford one big-budget production. The studio decided to shelve another historical epic, Crusade, after its budget reached nine figures [this had been another Verhoeven project; he must really hate Harlin and Davis!], and concentrate purely on Island. This was, in effect, a last throw of the dice for the beleaguered company and they financed the production, with its expected $60 million budget, largely by pre-selling distribution rights to overseas investors.

However, trouble was brewing, as Harlin apparently kept beefing up Davis’s role, at the expense of Michael Douglas’s. Said the actor, “I just was not comfortable with the part. The combination of not seeing it on the page and not knowing where it would go. I was feeling uncomfortable, and I wanted out… Ultimately, comes one day, and the director says, ‘I’m happy with the direction the script is going.’ And I said: ‘God bless you. I’m not.’ ” No-one at Carolco either saw fit or was able to override Harlin, so Douglas left the project. Both Harlin and Davis expected it to fold entirely due to his departure, but Carolco had no way back from the financial abyss into which they had flung themselves, and had to go forward, holding both director and star to their contracts.

Harlin later recounted: “At that point I was left there with my then-wife, Geena Davis and myself, and a company that was already belly-up. We begged to be let go. We begged that we didn’t have to make this movie. We begged that we not be put in this position.” Davis concurs: “I, of course, assumed the whole project would be canceled. It was all based on Michael Douglas’s being in it. To my horror, I learned not only would they not cancel, but that I had a legal obligation to go ahead, unlike Michael. I tried desperately to get out of this movie.” Instead, Douglas was replaced by the considerably lower profile (and far cheaper) Matthew Modine. Yet even he was unhappy, complaining, “They didn’t give me the [new] script. They gave me the script that Michael had said yes to… It was about a guy and a girl, but when I arrived in Malta, it [had become] about a girl and her journey.”

Ah, yes. Malta. The film was to be shot there and in Thailand, and pre-production had to go on, despite no leading man, and with the script a work in progress. But why let that interfere? In a memo, Harlin wrote, “When the casting concerns have been resolved and I arrive in Malta, I want to see the most spectacular and eye-popping sets, the most interesting and unusual props, and especially weapons and special effects that leave the audience gasping in awe and stunts that no one thought possible before. No sequence or setting that you’ve seen in movies before is good enough. Any idea that has been previously used has to be reinvented and cranked up 10 times.” Seems a strange kind of message from someone supposedly desperate to get off the project, unless he was trying to push costs to a level where even Carolco would have to cry “Enough!” This theory might help explain stories like Harlin allegedly spending $15,000 to expedite getting his dog through Maltese quarantine.

There, the design team had to build its sets on spec, only to incur the extra costs of rebuilding them after Harlin finally arrived in Malta. Chief camera operator Nicola Pecorini quit, and two dozen crew members left in sympathy. A director of photography broke his leg in an accident. Raw sewage leaked into one of the tanks where actors were supposed to swim. While no-one questions the efforts of either Harlin or Davis, costs continued to escalate as the shoot moved to the Far East, where an inexperienced team struggled with the logistics of filming a largely water-bound production. The total cost of producing, distributing and marketing the film ended up at $121 million. Considering only four films released in 1995 took even $110 million at the US box-office, the chances of Island saving Carolco’s bacon were slim indeed. Indeed, it was already too late. If triggering a financial meltdown was Harlin’s aim, he succeeded; the company didn’t survive long enough to see Island in cinemas, declaring bankruptcy six weeks before its release in December 1995.

There, the design team had to build its sets on spec, only to incur the extra costs of rebuilding them after Harlin finally arrived in Malta. Chief camera operator Nicola Pecorini quit, and two dozen crew members left in sympathy. A director of photography broke his leg in an accident. Raw sewage leaked into one of the tanks where actors were supposed to swim. While no-one questions the efforts of either Harlin or Davis, costs continued to escalate as the shoot moved to the Far East, where an inexperienced team struggled with the logistics of filming a largely water-bound production. The total cost of producing, distributing and marketing the film ended up at $121 million. Considering only four films released in 1995 took even $110 million at the US box-office, the chances of Island saving Carolco’s bacon were slim indeed. Indeed, it was already too late. If triggering a financial meltdown was Harlin’s aim, he succeeded; the company didn’t survive long enough to see Island in cinemas, declaring bankruptcy six weeks before its release in December 1995.

The film, to be honest, never really had a chance. Originally intended as a summer release, the production problems led to it being pushed back, and for some inexplicable reason it was sent to cinemas the weekend before Christmas, which was then hardly a tent-pole date for action blockbusters. Critical reaction was mixed, though hardly disastrous: it’s rated 37% fresh on RottenTomatoes.com, but Roger Ebert gave it three stars out of four, saying, “Cutthroat Island is everything a movie named Cutthroat Island should be, and no more.” The audience, however, ignored it entirely. It opened at #11, taking in less than $2.4 million its opening weekend, and finishing below the likes of other openers such as Jean-Claude Van Damme’s Sudden Death or entirely forgotten family adventure Tom and Huck.

Those involved generally seem to look back on the results with fondness, though Modine expressed some bitterness at the time: “It’s the first movie I’ve worked on where the director never really spoke to me. It was frustrating and Renny spent a lot of his time just finding new ways to blow things up. He likes to blow things up.” His opinion seems to have mellowed, and he now says, “I’m still very pleased with the movie. I think that the movie was terribly harshly criticized. It’s a pirate movie! And it was attacked as though we tried to remake Gone With the Wind or something. It’s a really fun movie.” Davis agrees, saying, “The fact is, Renny and I are really proud of the movie,” and Harlin thinks, “It’s not Pirates of the Caribbean, but I think it’s a totally fine sort of family and young people’s pirate adventure. And I think that people just ganged [up] against it because it failed at the box office.”

Those involved generally seem to look back on the results with fondness, though Modine expressed some bitterness at the time: “It’s the first movie I’ve worked on where the director never really spoke to me. It was frustrating and Renny spent a lot of his time just finding new ways to blow things up. He likes to blow things up.” His opinion seems to have mellowed, and he now says, “I’m still very pleased with the movie. I think that the movie was terribly harshly criticized. It’s a pirate movie! And it was attacked as though we tried to remake Gone With the Wind or something. It’s a really fun movie.” Davis agrees, saying, “The fact is, Renny and I are really proud of the movie,” and Harlin thinks, “It’s not Pirates of the Caribbean, but I think it’s a totally fine sort of family and young people’s pirate adventure. And I think that people just ganged [up] against it because it failed at the box office.”

Are people right to do so? Well, I’ll largely refer you over to our original review, though I did watch it again for the purposes of this piece. This time around, it seemed a film which should be more entertaining than it is, despite Harlin’s fondness for explosions – Modine was dead right there, with the director apparently oblivious to the fact that cannonballs were not rocket-propelled grenades that create giant fireballs on impact. Plausibility is utterly out the window, from the giant island with its sea-cliffs, hundreds of feet high, inexplicably missing from maps, through to the multiple zip-lines with which pirate vessels were apparently equipped. The dialogue certainly feels like it was made up on the fly, from virtually the heroine’s first line (“I took your balls”) to her last (“Bad Dawg!”). However, it doesn’t drag, and the main cast go at the material with sufficient energy to make for an entertaining two hours. I’ve seen far worse, much more successful films – hello, National Treasure.

One final, semi-ironic point. At the time, it was considered possible Hollywood would rein in the excess. as a result of the film’s failure. The following April, Daniel Jeffreys of The Independent wrote, “The films that have topped the box office list in the US since Cutthroat Island sank have had budgets well below $50m. Movies like Dead Man Walking, The Birdcage, Sense and Sensibility, 12 Monkeys and Mr Holland’s Opus have all cleared their modest costs with ease making three times as much money between them as Cutthroat Island lost. Next time Hollywood goes looking for buried treasure it might remember that and leave the lavish special effects at home.” But 20 years later, the top hits this year are Jurassic World, Avengers: Age of Ultron, Inside Out and Furious 7, whose production budgets alone – without distribution or marketing costs – average north of $190 million, making Island look positively restrained by comparison. Perhaps Renny and Geena were just ahead of their time, after all.

Your tolerance for this may well depend on your fondness for Modern Family, in which Vergara plays Gloria, who is much the same character: a Colombian spitfire trophy-wife. It works rather better there, as part of the broad palette of distinct individuals, and in an episode that lasts 30 minutes, including commercials. You get the sense she might not be too easy to live with, and the 85 minutes here does sometimes become more a slog than a pleasure, and we speak as big fans of Family. Here, rather than the wife of a closet magnate, Daniella Riva (Vergara) is married to the henchman of a drug lord, who gets gunned down after agreeing to testify against his employer (Cosio), just as the straight-laced Officer Cooper (Witherspoon) arrives to escort them to court. When it becomes clear some corrupt cops are in on the action, Cooper and Riva are forced to strike out on their own, making for an unlikely odd couple, whose spiky relationship grows over the course of their unscheduled road-trip.

Your tolerance for this may well depend on your fondness for Modern Family, in which Vergara plays Gloria, who is much the same character: a Colombian spitfire trophy-wife. It works rather better there, as part of the broad palette of distinct individuals, and in an episode that lasts 30 minutes, including commercials. You get the sense she might not be too easy to live with, and the 85 minutes here does sometimes become more a slog than a pleasure, and we speak as big fans of Family. Here, rather than the wife of a closet magnate, Daniella Riva (Vergara) is married to the henchman of a drug lord, who gets gunned down after agreeing to testify against his employer (Cosio), just as the straight-laced Officer Cooper (Witherspoon) arrives to escort them to court. When it becomes clear some corrupt cops are in on the action, Cooper and Riva are forced to strike out on their own, making for an unlikely odd couple, whose spiky relationship grows over the course of their unscheduled road-trip.

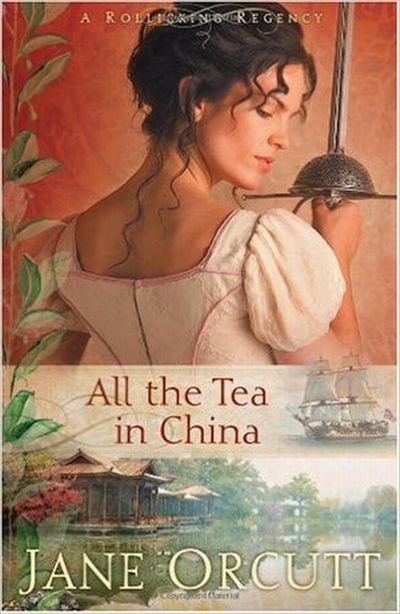

When I saw this book at a yard sale a few years ago, the captivating picture of a sword-wielding lady on the cover, coupled with the knowledge that the book is a romance by an evangelical Christian author, convinced me that this read would be right up my wife’s alley. I wasn’t wrong; she was initially skeptical of the historical setting (being more into modern settings), but once she got into it, she “couldn’t put it down.” She in turn recommended it to me; and obviously my reaction was positive as well!

When I saw this book at a yard sale a few years ago, the captivating picture of a sword-wielding lady on the cover, coupled with the knowledge that the book is a romance by an evangelical Christian author, convinced me that this read would be right up my wife’s alley. I wasn’t wrong; she was initially skeptical of the historical setting (being more into modern settings), but once she got into it, she “couldn’t put it down.” She in turn recommended it to me; and obviously my reaction was positive as well!