★★★★★

★★★★★

“She’s got legs… And she knows how to use them.”

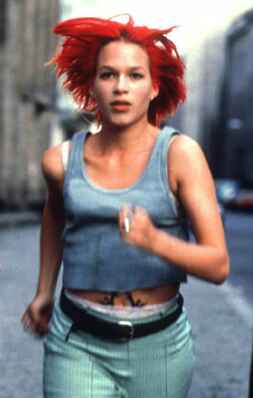

The term “action heroine” moves into a whole new dimension with this movie: no gun-battles, no fight-scenes, no explosions, but it still maintains a breathless pace for almost the entire 81 minutes. Lola (Potente) needs to find DM100,000 in 20 minutes, after her boyfriend Manni (Bleibtreu) loses a bag of money he was supposes to deliver to a highly dubious character. All this is set up in about five minutes, and then Lola is off, sprinting to try and get the cash.

The term “action heroine” moves into a whole new dimension with this movie: no gun-battles, no fight-scenes, no explosions, but it still maintains a breathless pace for almost the entire 81 minutes. Lola (Potente) needs to find DM100,000 in 20 minutes, after her boyfriend Manni (Bleibtreu) loses a bag of money he was supposes to deliver to a highly dubious character. All this is set up in about five minutes, and then Lola is off, sprinting to try and get the cash.

The key twist is the film depicting three parallel stories; all start with her leaving her apartment, but they gradually diverge, and end in three radically different conclusions. One of the film’s myriad delights is seeing how they interweave, with the differing fates of the various characters, and how tiny changes in the decisions we make can have massive consequences.

Right from the start, when Lola lobs a phone in the air and it lands spot-on the cradle, we know she has unusual powers. Her screams can shatter glass, and there’s one moment, in the casino, when she turns to the manager and looks at him. “Just one more game”, she says, and as portrayed by Potente (an amazing performance, with “future star” written through it), her gaze comes across as a force of nature more powerful than a typhoon. Lola is someone absolutely determined to have what she wants – “love conquers all”, if you like – and she even seems capable of rewinding time through sheer will, when the results go against her.

Yet, curiously, certain experiences appear to carry forward: in run #1, she is shown how to use a gun, in run #2, she needs no such tuition. A security guard we see clutching his heart in #2, is met in an ambulance in #3. Tykwer sees no need to explain any of this (is it merely being played out in Lola’s mind?), yet spotting these things are part of what makes the film so incredibly rewatchable. Even after half-a-dozen viewings, I’m still finding new facets e.g. the number she bets on in the casino, 20, is also the number of minutes she has to save Manni, since there’s simply so much crammed in.

Special mention needs to be made of the soundtrack, a pumping mix of techno co-created by Tykwer, which helps drive the film along at a blistering pace, and is one of the few soundtracks I will listen to on their own. Yet there are also tender moments (probably essential to prevent the audience from hyperventilating and going into shock), which Tykwer handles with skill and aplomb. Lola is something of an aberration in his filmography, stylistically: his other work such as Winter Sleepers are much more languidly-paced, but do cover similar themes of randomness and its effects. The end result is a film which manages to be shallowly entertaining and deeply satisfying at the same time. You can enjoy it purely on a “what happens next?” level, or appreciate it as something with so much depth that it can even be viewed as a retelling of the myth of Orpheus (the evidence pointing to such an interpretation is too lengthy to go into here). Truly a film with something for everyone, and for some, like myself, it has everything.

Special mention needs to be made of the soundtrack, a pumping mix of techno co-created by Tykwer, which helps drive the film along at a blistering pace, and is one of the few soundtracks I will listen to on their own. Yet there are also tender moments (probably essential to prevent the audience from hyperventilating and going into shock), which Tykwer handles with skill and aplomb. Lola is something of an aberration in his filmography, stylistically: his other work such as Winter Sleepers are much more languidly-paced, but do cover similar themes of randomness and its effects. The end result is a film which manages to be shallowly entertaining and deeply satisfying at the same time. You can enjoy it purely on a “what happens next?” level, or appreciate it as something with so much depth that it can even be viewed as a retelling of the myth of Orpheus (the evidence pointing to such an interpretation is too lengthy to go into here). Truly a film with something for everyone, and for some, like myself, it has everything.

Dir: Tom Tykwer

Stars: Franka Potente, Moritz Bleibtreu, Herbert Knaup, Nena Petri

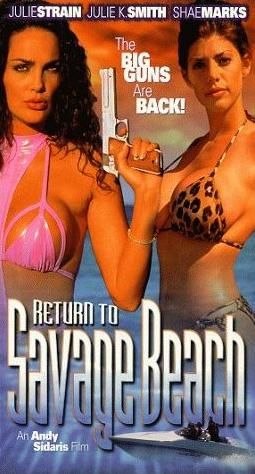

This was Sidaris’s last film, and after the disappointment of Warrior, it’s nice to see him return to a more straightforward approach, with little of the post-modernity attempted there. It is largely a sequel to Savage Beach, with a raid on the LETHAL offices puzzling Willow (Strain) and her agents, because the only thing accessed was the files on that case, which have long been closed. However, it turns out the villain there, Rodrigo (Obregon) did not die in a fiery, explosive-tipped crossbow bolt explosion as thought, and now sports a nifty mask, apparently lifted from a production of Phantom of the Opera. He sends his blonde minion in her submarine(!), along with his ninjas(!!), back to the island to claim a priceless Golden Buddha buried there, and it’s up to Cobra (Smith), Tiger (Marks) and their himbo colleagues, to stop him.

This was Sidaris’s last film, and after the disappointment of Warrior, it’s nice to see him return to a more straightforward approach, with little of the post-modernity attempted there. It is largely a sequel to Savage Beach, with a raid on the LETHAL offices puzzling Willow (Strain) and her agents, because the only thing accessed was the files on that case, which have long been closed. However, it turns out the villain there, Rodrigo (Obregon) did not die in a fiery, explosive-tipped crossbow bolt explosion as thought, and now sports a nifty mask, apparently lifted from a production of Phantom of the Opera. He sends his blonde minion in her submarine(!), along with his ninjas(!!), back to the island to claim a priceless Golden Buddha buried there, and it’s up to Cobra (Smith), Tiger (Marks) and their himbo colleagues, to stop him.

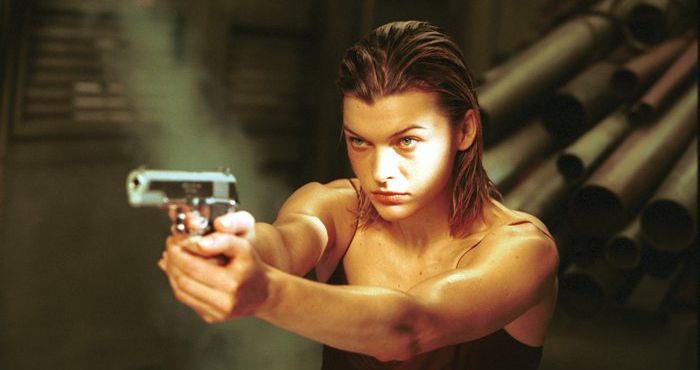

Interestingly, in the past year, all three of the computer-game to movie adaptations have had heroines: Lara Croft, Aki (Final Fantasy), and now, Resident Evil‘s Alice, who wakes up one day with a splitting headache and no memory. I’ve had mornings like that too. However, I never found myself kidnapped by a SWAT team and dragged into the Hive, an underground complex populated by the walking dead (human

Interestingly, in the past year, all three of the computer-game to movie adaptations have had heroines: Lara Croft, Aki (Final Fantasy), and now, Resident Evil‘s Alice, who wakes up one day with a splitting headache and no memory. I’ve had mornings like that too. However, I never found myself kidnapped by a SWAT team and dragged into the Hive, an underground complex populated by the walking dead (human  This is to…er, well, I think it was to disarm the computer, but I’m not certain about that. Mind you, I’m not certain about quite a lot in this movie. The characterisation is so woeful, I managed to combine two opposing characters into one for the entire film. And it still made sense – indeed, even after Chris enlightened me, I felt my version was better. My version would also have discarded the clock countdown, or used it as the basis for an exciting race against time through the tunnels. What’s the point of a countdown, if you don’t see it in the last ten minutes? There’s also maddeningly shallow nods to Lewis Carroll: the heroine is called Alice, who goes down a “rabbit hole”, while the computer is the Red Queen with a fondness for lopping off peoples’ heads. You should either do this stuff to the hilt, or not at all.

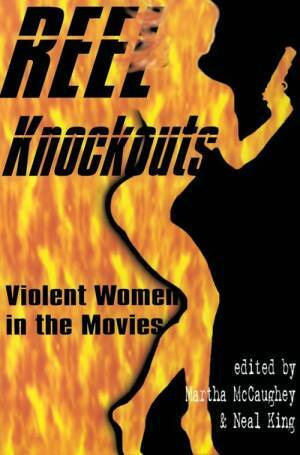

This is to…er, well, I think it was to disarm the computer, but I’m not certain about that. Mind you, I’m not certain about quite a lot in this movie. The characterisation is so woeful, I managed to combine two opposing characters into one for the entire film. And it still made sense – indeed, even after Chris enlightened me, I felt my version was better. My version would also have discarded the clock countdown, or used it as the basis for an exciting race against time through the tunnels. What’s the point of a countdown, if you don’t see it in the last ten minutes? There’s also maddeningly shallow nods to Lewis Carroll: the heroine is called Alice, who goes down a “rabbit hole”, while the computer is the Red Queen with a fondness for lopping off peoples’ heads. You should either do this stuff to the hilt, or not at all. The above quote, from one essay in this collection of pieces on “violent women in the movies”, perhaps sums up its main problem. I cheerfully admit that my writing is skewed heavily towards the former point of view, but even so, too many of the authors here seem concerned with squeezing meanings out of films that were never intended to be there. This over-analytical approach results in the book swinging between thought-provoking and infuriating on almost every page.

The above quote, from one essay in this collection of pieces on “violent women in the movies”, perhaps sums up its main problem. I cheerfully admit that my writing is skewed heavily towards the former point of view, but even so, too many of the authors here seem concerned with squeezing meanings out of films that were never intended to be there. This over-analytical approach results in the book swinging between thought-provoking and infuriating on almost every page.