“I would like to see every woman know how to handle guns, as naturally as they know how to handle babies.”

This article was largely inspired by the grainy, less than thirty second film clip above. It shows Wild West heroine Annie Oakley in action, filmed by none other than Thomas Edison on November 1, 1894 in his ‘Black Maria’ facility, one of the earliest films made at the world’s first film production studio. It’s weird to watch something made by one icon of American culture, and featuring another. It feels like seeing a photograph of Robin Hood, taken by Leonardo da Vinci, and is a reminder that Annie Oakley was a real person, not a mythical creation of Hollywood or the dime novelists. While the title here may be hyperbolic – obviously, there were other women to have picked up firearms before her – she was likely the first to achieve worldwide fame through her skill with a gun. As such, she certainly deserves a place in the action heroine Hall of Fame.

Born Phoebe Ann Mosey in 1860, she seems to have had a pretty crappy childhood. Her father died when she was five, and Annie became a ward of Darke County, Ohio, in 1870. From there, she was fostered out to a family, who apparently treated her as little more than a slave. She ran away from them a couple of years later, eventually returning to live with her mother, who had remarried, at age 15. But by this point, she was already well-versed in guns, having been hunting with them since she was eight. Her skill with them gradually became known through the region, and led to the shooting match against Frank Butler which propelled her towards greater fame, and a career as a professional markswoman.

There’s some uncertainty about when this took place. Some sources say 1875, while others prefer 1881. The details seem fairly well-established. Frank Butler, part of a travelling show, visited Cincinnati, and laid a bet with a local hotel owner that he could beat any local shooter. The hotelier brought in Annie as his champion, and she won, when Butler missed his 25th shot. He may have lost the wager, but he didn’t come away empty-handed, as Butler married Annie in 1882. They began performing together, with Annie taking the stage name of Oakley, and three years later the married couple both became part of Buffalo Bill’s Wild West production [it never included the word “show” in its title], which had begun touring America in 1883.

Performances typically opened with a parade of horse and riders from many nations, including the military and Indians. It proceeded through a series of re-enactments, such as of the Pony Express or an attack on a wagon train, and also included displays of skills related to life on the frontier, including trick riding, roping and marksmanship. While Oakley was the best-known woman to take part in the shows, she wasn’t the only one. In 1886, another trick shooter, Lillian Smith, also joined Buffalo Bill while still a teenager, and by most accounts, there was a fractious relationship between the two, with them having markedly different personalities and styles. Another Western icon, Calamity Jane, began appearing as a storyteller in 1893. Records indicate that Buffalo Bill paid the women the same as their male equivalents, though Oakley earned more than anyone save Bill himself.

It was as part of his show that Oakley’s fame achieved its peak, and not just in the United States. She was part of the company which toured Europe on multiple occasions from 1887 on, performing for many of the fabled “crowned heads of Europe,” including Queen Victoria and King Umberto I of Italy. In 1890, she reportedly used Germany’s Kaiser Friedrich Wilhelm II as an assistant for one of her stunts, shooting the end off a cigar he held, a trick she usually performed on her husband. Europe might have been rather different, if Annie’s skills had not been up to the task. For Kaiser Wilhem was one of the more aggressive leaders whose subsequent actions helped trigger World War I, making Oakley’s prowess very much one of the “what if” moments in the continent’s history.

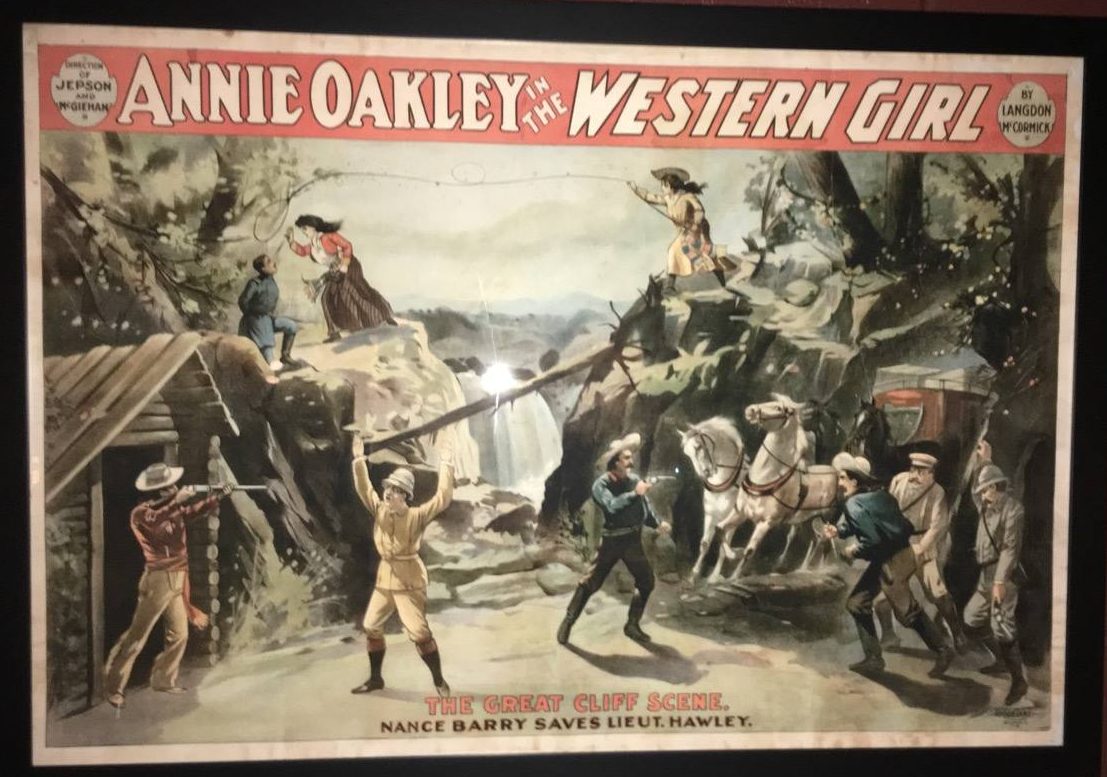

Her other stunts, if perhaps slightly less risky to the target, were little if any less impressive. She could find her target while facing away from it, sighting her gun backwards over her shoulder, using a mirror (left), or even the blade of a knife. She could also hit the edge of a playing card at thirty paces, or dimes tossed in the air. Her partner could throw four glass balls up, while Annie wasn’t even holding her rifle. Before they landed, she could pick up the gun and shoot them down. But in 1901, she was injured in a train accident, which left her needing multiple operations on her spine. The after-effects forced her into retiring from Bill’s company, though she still performed, starring in a stage play written especially for her by Langdon McCormick, The Western Girl. In it, her character Nance Barry saves the hero and wins his heart. It couldn’t possibly be any other way.

Annie’s life was hardly less interesting after her time with Buffalo Bill. In 1904, she took on press magnate Randolph Hearst, after two of his Chicago newspapers published a story headlined, “Famous Woman Crack Shot Steals to Secure Cocaine.” Turns out, the criminal was actually a burlesque performer who used the stage name “Any Oakley”. Hearst refused to retract the story, so Oakley ended up suing no less than 55 newspapers for libel, over the next six years. She won all but one of the cases, though the legal fees involved meant she ended up losing money, as she redeemed her good name.

She was far ahead of her time on the topic of women in combat. In April 1898, with the Spanish-American war about to break out, she wrote to the then-President, William McKinley, as follows:

She was far ahead of her time on the topic of women in combat. In April 1898, with the Spanish-American war about to break out, she wrote to the then-President, William McKinley, as follows:

Dear Sir, I for one feel confident that your good judgment will carry America safely through without war. But in case of such an event I am ready to place a company of fifty lady sharpshooters at your disposal. Every one of them will be an American and as they will furnish their own Arms and Ammunition will be little if any expense to the government.

Her offer was, sadly, declined, despite the clearly positive economics. In terms of sharp-shooting, it would have been very interesting to see what Oakley might have done in a war situation. I like to think she might have surpassed sniper Lyudmila Pavlichenko’s mark of 309 victims from World War II. Certainly, her skills didn’t desert Annie with age. At the age of 62, in a North Carolina shooting contest, she hit 100 clay targets in a row from a distance of 16 yards. As the photograph (right) shows, she was clearly still enjoying the sport well into her sunset year.

However, she died of pernicious anemia in 1926, at the age of 66. Her husband, Frank Butler passed away just 18 days later, with some reports saying he simply stopped eating after her death, apparently losing the will to live. But what Oakley represents lives on, not least in a host of books, movies and TV series in which she appeared, portrayed by actresses from Barbara Stanwyck to Geraldine Chaplin and Jamie Lee Curtis. The cultural fascination for her endures. In 2012, an auction of items owned by Oakley brought in over half a million dollars: a shotgun used on the 1887 European tour went for $143,400 and even her stetson hat reached $17,925.

Annie arguably stands as the first woman to make a career as a professional action heroine. Her legend will survive – and deservedly so.

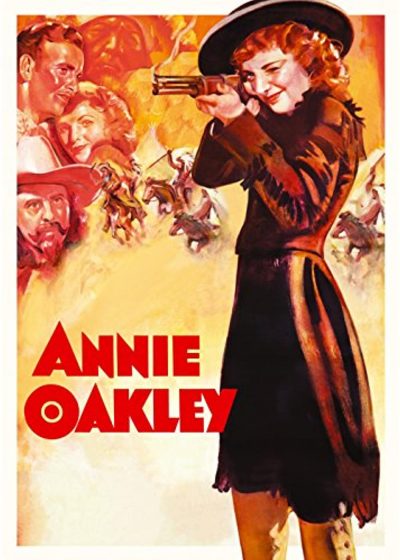

Annie Oakley (film)

By Jim McLennan★★★

“Annie Gets Her Gun.”

While not exactly an accurate retelling of the life of noted sure-shot Annie Oakley, this is breezily entertaining. Indeed, you can make a case for this being one of the earliest “girls with guns” films to come out in the talking pictures era. There’s no denying Oakley (Stanwyck) qualifies here. The first time we see her, she’d delivering a load of game birds – all shot through the head to avoid damaging the flesh – to her wholesaler. When barnstorming sharpshooter Toby Walker (Foster) blows into town, Annie ends up in a match with him, which she ends up throwing, due in part to her crush on him. She still gets a job alongside Walker, in the Wild West show run by the renowned ‘Buffalo Bill’ Cody (Olsen) and his partner, Jeff Hogarth (Douglas). But Annie and Toby’s relationship fractures after he accidentally shoots her in the hand, while concealing an injury affecting his sight.

While not exactly an accurate retelling of the life of noted sure-shot Annie Oakley, this is breezily entertaining. Indeed, you can make a case for this being one of the earliest “girls with guns” films to come out in the talking pictures era. There’s no denying Oakley (Stanwyck) qualifies here. The first time we see her, she’d delivering a load of game birds – all shot through the head to avoid damaging the flesh – to her wholesaler. When barnstorming sharpshooter Toby Walker (Foster) blows into town, Annie ends up in a match with him, which she ends up throwing, due in part to her crush on him. She still gets a job alongside Walker, in the Wild West show run by the renowned ‘Buffalo Bill’ Cody (Olsen) and his partner, Jeff Hogarth (Douglas). But Annie and Toby’s relationship fractures after he accidentally shoots her in the hand, while concealing an injury affecting his sight.

This hits the ground running, and roughly the first third plays decades ahead of its time. Don’t forget, this was made only fifteen years after women were granted the right to vote across the entire United States. Its depiction of a strong, perfectly independent woman as personified by Stanwyck is great – there’s also Walker’s former “friend,” Vera Delmar (Perl Kelton). When sternly warned the saloon she’s about to enter is no place for a lady, she breezily replies, “Oh, I’m no lady.” I’m quite impressed this was able to get through, given the rigid imposition of the strict Hays Code, beginning the previous year, with its goal “that vulgarity and suggestiveness may be eliminated.”

Almost inevitably, it can’t maintain this pace. There’s too much footage of the Wild West Show, which seems to consist largely of people on horses milling around the arena. I guess people were easily satisfied in those days. Meanwhile, the romance between Oakley and Walker (an entirely artificial construction, with Walker never existing as an actual person), fails to be convincing. Somewhat more interesting is the portrayal of Chief Sitting Bull, the Native American warrior who also became part of Wild Bill’s show. While depicted largely for comic relief – witness the scene where he turns out the gas lights in his bedroom by shooting at them – he is played by a genuine Indian, Chief Thunder Bird, which is considerably more progressive than some movies. He is also instrumental in Annie and Toby’s reconciliation.

Stanwyck does an excellent job of depicting the heroine, portraying her as someone absolutely confident in her own talents. I’d like to have seen more development of her character: as is, the one we see delivering quail at the start of the film, is almost identical to the one we see making up with Toby in its final shot. Sadly, the subject didn’t live to see her life immortalized in film, having died nine years before this was released. I think she’d probably have been quite pleased with her depiction.

Dir: George Stevens

Star: Barbara Stanwyck, Preston Foster, Melvyn Douglas, Moroni Olsen

Annie Oakley of the Wild West, by Walter Havighurst

By Jim McLennan★★

“An appetiser rather than a main course, that diverts from the topic far too often.”

Annie Oakley was one of the earliest “girls with guns”. In her role as a sharpshooter, performing with the likes of Buffalo Bill’s Wild West show, she travelled the globe, appearing in front of Presidents, Kings and Emperors. She shot a cigarette held by the future Kaiser Wilhelm of Germany (accuracy later deplored by American newspapers, after the nations went to war in 1917). At 90 feet, she could shoot a dime tossed in midair, or hit the edge of a playing card, then add five or six more holes as it fluttered to the ground. In seventeen years and 170,000 miles of travel, she only missed four shows, and even in her sixties, could still take down a hundred clay pigeons in a row.

Annie Oakley was one of the earliest “girls with guns”. In her role as a sharpshooter, performing with the likes of Buffalo Bill’s Wild West show, she travelled the globe, appearing in front of Presidents, Kings and Emperors. She shot a cigarette held by the future Kaiser Wilhelm of Germany (accuracy later deplored by American newspapers, after the nations went to war in 1917). At 90 feet, she could shoot a dime tossed in midair, or hit the edge of a playing card, then add five or six more holes as it fluttered to the ground. In seventeen years and 170,000 miles of travel, she only missed four shows, and even in her sixties, could still take down a hundred clay pigeons in a row.

So why is this book unsatisfactory? Largely because much of it isn’t actually about her. Originally written in 1954, Havighurst uses Oakley as a key to write about…well, everything else connected to her, and you’ll find half a dozen pages passing without any mention of its supposed subject. The author goes off the track with alarming frequency: Buffalo Bill, a.k.a. William Cody, is the main beneficiary, and someone unschooled in the topic will learn almost as much about him as Oakley. There are some effective moments, particularly when Havighurst depicting the loving relationship between Annie and her husband, Frank Butler, whom she met while outshooting him in Cincinnati. Married for over fifty years, they died less than three weeks apart. But such passages are few and far between; the actual Oakley-related content of the book is disappointing, though I’m now keen to track down a better work on the topic.

By: Walter Havighurst

Publisher: Castle Books [$8.98 from HalfPrice Books]

Annie Oakley (TV series)

By Jim McLennan★★★

“One of the first TV action heroines; for 50 years old, better than you might expect.”

This TV series was Gene Autry’s idea; he wanted to give little girls a western star of their own, and created a show based on the character of Oakley, the most famous sharpshooter of all time. In his version, she lives in Diablo with her brother Tagg (Hawkins) and keeps the town safe along with deputy Lofty Craig (Johnson) – the sheriff, Annie’s uncle Luke, was somehow very rarely around… It ran for 81 episodes from January 1954 to February 1957; two DVDs, with five first season stories on each, have been released by Platinum – you can get the box set of both for $5.99, which is a steal.

This TV series was Gene Autry’s idea; he wanted to give little girls a western star of their own, and created a show based on the character of Oakley, the most famous sharpshooter of all time. In his version, she lives in Diablo with her brother Tagg (Hawkins) and keeps the town safe along with deputy Lofty Craig (Johnson) – the sheriff, Annie’s uncle Luke, was somehow very rarely around… It ran for 81 episodes from January 1954 to February 1957; two DVDs, with five first season stories on each, have been released by Platinum – you can get the box set of both for $5.99, which is a steal.

Given its age, it’s no surprise that this is certainly a little hokey, but is by no means unwatchable. The writers cram a lot into each 25-minute episode, and Oakley is a sharp-witted heroine, in most ways years ahead of the usual portrayal of women (though still afraid of mice!) – she’d probably be a better deputy than Lofty! It certainly helped that Davis, a mere 5’2″, was a skilled rider herself, and did most of her own stunts. However, this being a 50’s TV show, there are limits. Annie never kills anyone, preferring to shoot the gun from their hand, while fisticuffs are left to Lofty, though at least one ep (Annie and the Lily Maid) has an unexpected mini-catfight.

Perhaps the best episode on the DVDs is Justice Guns, where an ex-marshal with failing sight seeks revenge on the man who shot his brother. Annie has to try and solve the situation, and while you know she will survive, the lawman’s fate is much less certain as the four o’clock shootout approaches. In a series that is, even I will admit, often sugary and predictable, this has genuine tension, and that’s something which five decades haven’t changed one bit.

Star: Gail Davis, Brad Johnson, Jimmy Hawkins

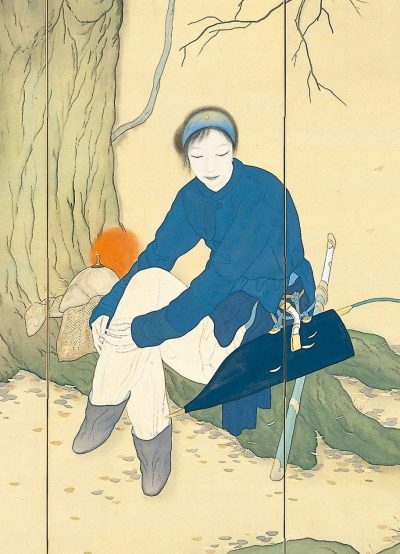

The picture of Hua-Mu Lan enlisting as a soldier instead of her father, was painted by Pan-Li shui on Dalongdong Baoan Temple

The picture of Hua-Mu Lan enlisting as a soldier instead of her father, was painted by Pan-Li shui on Dalongdong Baoan Temple Much as the story of Robin Hood can be told as a parable against contemporary corrupt leaders, so Mulan’s bravery and loyalty can provide a heroic figure to contrast with current events. This applies to cinematic versions of the story, as well as the written, though it can work for the authorities as well. 1939’s Mulan Joins the Army, is unabashedly pro-military and jingoistic, as its title suggests. It’s unsurprising – China was at war with Japan at the time – but stressing the benefits to be gained by soldiers was a helpful recruitment tool. More on this topic below.

Much as the story of Robin Hood can be told as a parable against contemporary corrupt leaders, so Mulan’s bravery and loyalty can provide a heroic figure to contrast with current events. This applies to cinematic versions of the story, as well as the written, though it can work for the authorities as well. 1939’s Mulan Joins the Army, is unabashedly pro-military and jingoistic, as its title suggests. It’s unsurprising – China was at war with Japan at the time – but stressing the benefits to be gained by soldiers was a helpful recruitment tool. More on this topic below. The sound of one sigh after another, as Mulan weaves at the doorway.

The sound of one sigh after another, as Mulan weaves at the doorway. Y’know, considering this is now more than eighty years old, this was likely better than I expected. Chen makes for a solid and engaging heroine, right from the start, when she tricks the residents of a nearby village, who demand she hand over the proceeds of her hunting [I am hoping the dead bird which plummets to the ground with an arrow through it, less than three minutes in, was a stunt avian…]

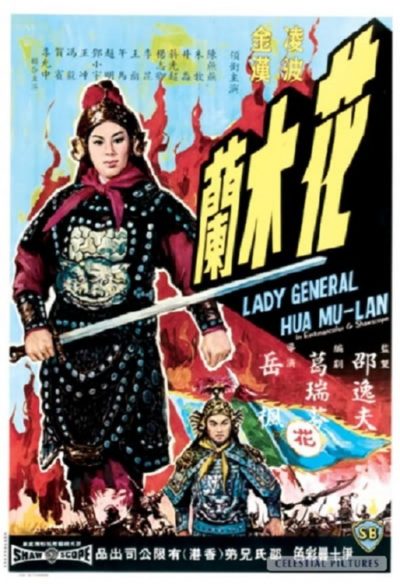

Y’know, considering this is now more than eighty years old, this was likely better than I expected. Chen makes for a solid and engaging heroine, right from the start, when she tricks the residents of a nearby village, who demand she hand over the proceeds of her hunting [I am hoping the dead bird which plummets to the ground with an arrow through it, less than three minutes in, was a stunt avian…] I probably should have done a bit more research before adding this to the list of versions for review here. I saw a sixties movie made by Shaw Brothers with that title, and presumed there would be kung-fu. Boy, was I wrong. There’s about one significant scene, which pits Mulan (Po) and some of her new army colleagues against each other. And that’s it. Oh, there is a battle between Imperial and invading forces. This might have contained some action, but was so poorly photographed – mostly due to incredibly bad lighting – that it was impossible to tell. What there was, instead, was singing.

I probably should have done a bit more research before adding this to the list of versions for review here. I saw a sixties movie made by Shaw Brothers with that title, and presumed there would be kung-fu. Boy, was I wrong. There’s about one significant scene, which pits Mulan (Po) and some of her new army colleagues against each other. And that’s it. Oh, there is a battle between Imperial and invading forces. This might have contained some action, but was so poorly photographed – mostly due to incredibly bad lighting – that it was impossible to tell. What there was, instead, was singing.

D

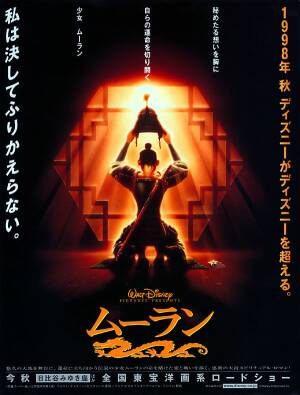

D isney movies are not the usual place to find action heroines: their classic woman is a princess, who sits in a castle and waits for someone of appropriately-royal blood to come and rescue her from whatever evil fate (wicked stepmother, poisoned spinning wheel, etc.) that has befallen her.

isney movies are not the usual place to find action heroines: their classic woman is a princess, who sits in a castle and waits for someone of appropriately-royal blood to come and rescue her from whatever evil fate (wicked stepmother, poisoned spinning wheel, etc.) that has befallen her. There’s also no threat of execution when her deception is found out – Chinese culture may perhaps actually have a more tolerant approach to such things, though this is admittedly going only by the likes of Peking Opera, and a good chunk of Brigitte Lin’s career. And, of course, both the romantic angle and amusing sidekick were modern additions. This contrasts sharply with one version of the original, which has the Emperor hearing of Mulan’s exploits, and demanding she becomes his concubine. Mulan commits suicide in preference to this fate, an ending that, for some reason, didn’t make it into the Disney adaptation…

There’s also no threat of execution when her deception is found out – Chinese culture may perhaps actually have a more tolerant approach to such things, though this is admittedly going only by the likes of Peking Opera, and a good chunk of Brigitte Lin’s career. And, of course, both the romantic angle and amusing sidekick were modern additions. This contrasts sharply with one version of the original, which has the Emperor hearing of Mulan’s exploits, and demanding she becomes his concubine. Mulan commits suicide in preference to this fate, an ending that, for some reason, didn’t make it into the Disney adaptation… That’s a shame, because the original still has a great deal to offer. Unlike many Disney films, the songs don’t bring proceedings to a grinding halt and are notably absent from the second half of the film. Indeed, the transition is deliberately abrupt: a band of happy, singing warriors is stopped mid-verse when they come across a burnt-out village which the Huns have exterminated (right). It’s a simple, but highly effective moment, where silence says a lot more than any words. [At one point a song for Mulan about the tragedy of war was considered, but this was dropped, along with Mushu’s song, Keep ‘Em Guessing – both decisions which can only be applauded.]

That’s a shame, because the original still has a great deal to offer. Unlike many Disney films, the songs don’t bring proceedings to a grinding halt and are notably absent from the second half of the film. Indeed, the transition is deliberately abrupt: a band of happy, singing warriors is stopped mid-verse when they come across a burnt-out village which the Huns have exterminated (right). It’s a simple, but highly effective moment, where silence says a lot more than any words. [At one point a song for Mulan about the tragedy of war was considered, but this was dropped, along with Mushu’s song, Keep ‘Em Guessing – both decisions which can only be applauded.] However, personally, I’d say the value of having a clearly non-Caucasian heroine (a first for any Disney film) outweighs relatively minor quibbles about subtext. It may be the last great hand-drawn animated feature from the studio which invented the genre, and all but defined it for sixty years, so I have absolutely no hesitation in recommending this as an empowering and highly entertaining tale for children – of any age, but especially those too young to read subtitles. There aren’t many action heroine films our entire family loves, but Mulan is definitely high on the list.

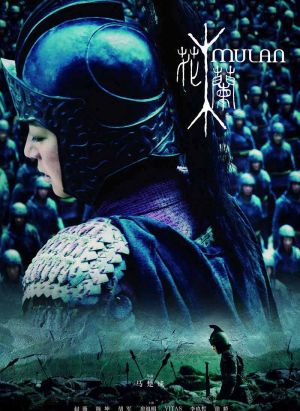

However, personally, I’d say the value of having a clearly non-Caucasian heroine (a first for any Disney film) outweighs relatively minor quibbles about subtext. It may be the last great hand-drawn animated feature from the studio which invented the genre, and all but defined it for sixty years, so I have absolutely no hesitation in recommending this as an empowering and highly entertaining tale for children – of any age, but especially those too young to read subtitles. There aren’t many action heroine films our entire family loves, but Mulan is definitely high on the list. Inspired by the same poem as Disney’s much-loved feature, this has the same basic idea – a young woman impersonates a man in order to save her father from being drafted in the army. However, this takes a rather different approach, being much darker in tone, not that’s this is much of a surprise, I guess. It’s also a lot longer in scope, with Mulan (Zhao, whom you may recognize as the heroine/goalkeeper from Shaolin Soccer), rather than fighting a single campaign, becoming a career soldier and rising through the ranks as a result of her bravery in battle, eventually becoming a general, tasked with defending the Wei nation from the villainous Mendu (Hu). He has killed his own father in order to take control, and has united the nomadic tribes of the Rouran, amassing an army of 200,000 to invade Mulan’s home territory. She comes up with a plan to lure him into a trap, but when she is betrayed by a cowardly commander, things look bleak indeed for Mulan and Wentai (Chen), one of the few who know her secret.

Inspired by the same poem as Disney’s much-loved feature, this has the same basic idea – a young woman impersonates a man in order to save her father from being drafted in the army. However, this takes a rather different approach, being much darker in tone, not that’s this is much of a surprise, I guess. It’s also a lot longer in scope, with Mulan (Zhao, whom you may recognize as the heroine/goalkeeper from Shaolin Soccer), rather than fighting a single campaign, becoming a career soldier and rising through the ranks as a result of her bravery in battle, eventually becoming a general, tasked with defending the Wei nation from the villainous Mendu (Hu). He has killed his own father in order to take control, and has united the nomadic tribes of the Rouran, amassing an army of 200,000 to invade Mulan’s home territory. She comes up with a plan to lure him into a trap, but when she is betrayed by a cowardly commander, things look bleak indeed for Mulan and Wentai (Chen), one of the few who know her secret. ★★★

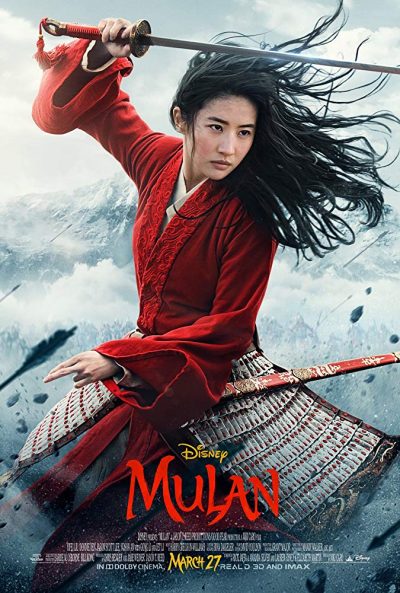

★★★ And make no mistake: I love the animated version: to me, it’s the best of the “new wave” of Disney features which began with Beauty and the Beast. It has a huge emotional range, perhaps more than any other Disney film outside Pixar, and can switch on a dime, going from cheerful song to grim destruction without jarring. I will also say, this is the first I’ve seen in Disney’s live-action adaptations of their animated catalog. All the others seemed entirely redundant, but this one seemed to offer scope for a different take on the subject. It does deliver on this expectation, but I can’t help feeling that, overall, more was lost here than gained.

And make no mistake: I love the animated version: to me, it’s the best of the “new wave” of Disney features which began with Beauty and the Beast. It has a huge emotional range, perhaps more than any other Disney film outside Pixar, and can switch on a dime, going from cheerful song to grim destruction without jarring. I will also say, this is the first I’ve seen in Disney’s live-action adaptations of their animated catalog. All the others seemed entirely redundant, but this one seemed to offer scope for a different take on the subject. It does deliver on this expectation, but I can’t help feeling that, overall, more was lost here than gained. I suppose this could be claimed to be a “mockbuster”, not so different from the sound-alike films released by The Asylum, e.g. Snakes on a Train. There’s no doubt this was made to ride the coat-tails of its far larger and better advertised big sister. And it’s not alone, with at least two other Chinese films apparently in production, one animated and the

I suppose this could be claimed to be a “mockbuster”, not so different from the sound-alike films released by The Asylum, e.g. Snakes on a Train. There’s no doubt this was made to ride the coat-tails of its far larger and better advertised big sister. And it’s not alone, with at least two other Chinese films apparently in production, one animated and the  Going into this, I was expecting it to be really terrible. After all, this Chinese animated version seemed to be little more than a mockbuster, riding on the trails of Disney’s

Going into this, I was expecting it to be really terrible. After all, this Chinese animated version seemed to be little more than a mockbuster, riding on the trails of Disney’s  When I

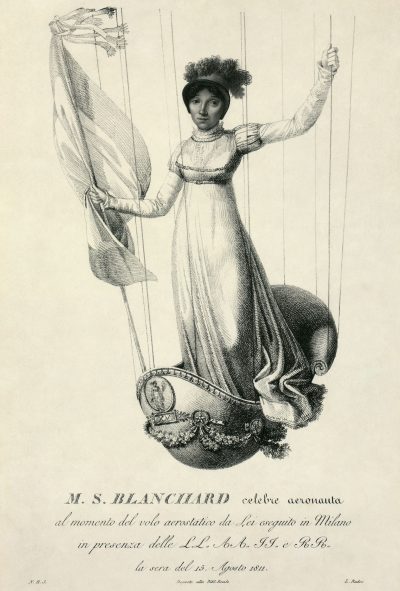

When I  For by this point, the novelty of merely seeing someone slowly ascend into the air had worn a bit thin. The Blanchards needed to jazz their spectacle up a bit to keep the crowds coming back. This included letting off fireworks from the balloon – a hazardous practice, given the inflammable nature of both the balloon and its gaseous contents – and tossing dogs out of the basket. Attached to those then recently-invented parachutes, I should add.

For by this point, the novelty of merely seeing someone slowly ascend into the air had worn a bit thin. The Blanchards needed to jazz their spectacle up a bit to keep the crowds coming back. This included letting off fireworks from the balloon – a hazardous practice, given the inflammable nature of both the balloon and its gaseous contents – and tossing dogs out of the basket. Attached to those then recently-invented parachutes, I should add. These exhibitions were not without incident. She flew over the Alps, and some of her flights lasted as long as 14½ hours, reaching a height of over 12,000 feet. At that height, the environment was so cold, icicles formed on her face, and she was in danger of passing out due to a lack of oxygen. In 1817, she almost drowned when her selected landing-spot turned out to be a marsh, and she became caught up in her craft’s rigging after touchdown. Only the fortuitous arrival of assistance saved her from a watery grave. However, it was only a stay of execution, rather than a pardon.

These exhibitions were not without incident. She flew over the Alps, and some of her flights lasted as long as 14½ hours, reaching a height of over 12,000 feet. At that height, the environment was so cold, icicles formed on her face, and she was in danger of passing out due to a lack of oxygen. In 1817, she almost drowned when her selected landing-spot turned out to be a marsh, and she became caught up in her craft’s rigging after touchdown. Only the fortuitous arrival of assistance saved her from a watery grave. However, it was only a stay of execution, rather than a pardon. And there ends 2019. Before we get on to looking at what’s to come in the action heroine arena for 2020, let’s quickly review what was saw this year from the film out of the

And there ends 2019. Before we get on to looking at what’s to come in the action heroine arena for 2020, let’s quickly review what was saw this year from the film out of the  Black Widow (1 May)

Black Widow (1 May) Mulan (27 Mar)

Mulan (27 Mar) Tribal Get Out Alive (9 Apr – UK)

Tribal Get Out Alive (9 Apr – UK)

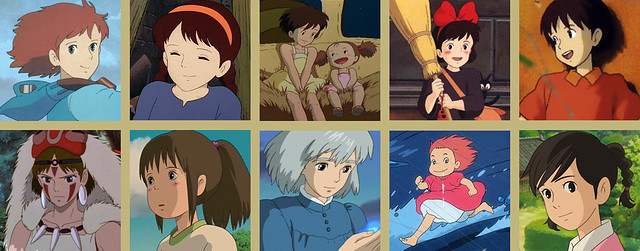

Indeed, their femininity is often virtually irrelevant. Gender-wise, you could swap many of them out with young men or boys, and little would need to be changed. I’d argue it’s the most effective kind of feminism: the sort which doesn’t need to shout about it, but simply gets on with doing and being, and leads by example rather than the creation of loud noises. Yet, as we’ll see, it’s a philosophy which cuts both ways. Being female does not necessarily make you a good person: they can be every bit as egotistical, prejudiced, cruel and willing to bring down hellfire and destruction, as any man. That’s true equality in cinematic action.

Indeed, their femininity is often virtually irrelevant. Gender-wise, you could swap many of them out with young men or boys, and little would need to be changed. I’d argue it’s the most effective kind of feminism: the sort which doesn’t need to shout about it, but simply gets on with doing and being, and leads by example rather than the creation of loud noises. Yet, as we’ll see, it’s a philosophy which cuts both ways. Being female does not necessarily make you a good person: they can be every bit as egotistical, prejudiced, cruel and willing to bring down hellfire and destruction, as any man. That’s true equality in cinematic action.

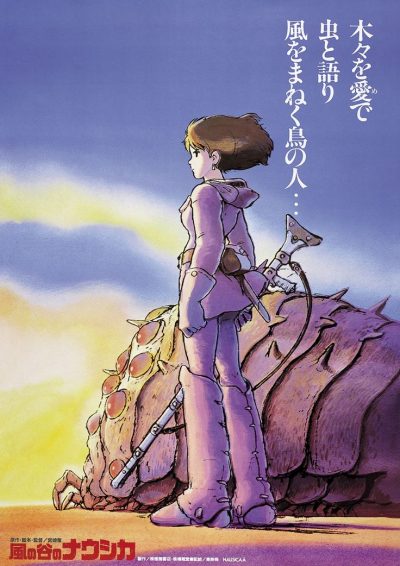

After the enormous critical, if not commercial, success of Lupin III: Castle of Cagliostro, Miyazaki was commissioned to create a manga series for Animage magazine, with a potential film adaptation attached. Publication began in early 1982, but it would take a dozen years, albeit of intermittent publication, before that story was complete. When the series’s popularity among Animage readers was established, work began on the film adaptation, covering the early portion of the manga. Since this was before Miyazaki’s own Studio Ghibli was founded, an external company, Topcraft, were commissioned to create the animation. The budget was only $1 million, with a mere nine-month production schedule leading up to its release in March 1984.

After the enormous critical, if not commercial, success of Lupin III: Castle of Cagliostro, Miyazaki was commissioned to create a manga series for Animage magazine, with a potential film adaptation attached. Publication began in early 1982, but it would take a dozen years, albeit of intermittent publication, before that story was complete. When the series’s popularity among Animage readers was established, work began on the film adaptation, covering the early portion of the manga. Since this was before Miyazaki’s own Studio Ghibli was founded, an external company, Topcraft, were commissioned to create the animation. The budget was only $1 million, with a mere nine-month production schedule leading up to its release in March 1984. Miyazaki’s father ran an airplane parts company in World War II, and even his film company, Studio Ghibli, was named after an Italian plane. Almost every one of his movies

Miyazaki’s father ran an airplane parts company in World War II, and even his film company, Studio Ghibli, was named after an Italian plane. Almost every one of his movies  To some extent, this was the film which “broke” Miyazaki in the West, being his first feature to receive an unedited theatrical release in America. It wasn’t a huge commercial success, taking only about $2.4 million in North America. But it was very well-received, Roger Ebert listing it among his top ten films of 1999. It likely opened the door for the success of Spirited Away, which would win Miyazaki the Oscar for Best Animated Feature at the 75th Academy Awards. But if I’m being honest, I don’t like it as much as many of his movies. While there’s no denying the imagination and enormous technical skill here, it doesn’t resonate emotionally with me in the same way. I think it’s probably the central character, who is relatively bland and uninteresting, even compared to other characters in the movie.

To some extent, this was the film which “broke” Miyazaki in the West, being his first feature to receive an unedited theatrical release in America. It wasn’t a huge commercial success, taking only about $2.4 million in North America. But it was very well-received, Roger Ebert listing it among his top ten films of 1999. It likely opened the door for the success of Spirited Away, which would win Miyazaki the Oscar for Best Animated Feature at the 75th Academy Awards. But if I’m being honest, I don’t like it as much as many of his movies. While there’s no denying the imagination and enormous technical skill here, it doesn’t resonate emotionally with me in the same way. I think it’s probably the central character, who is relatively bland and uninteresting, even compared to other characters in the movie.

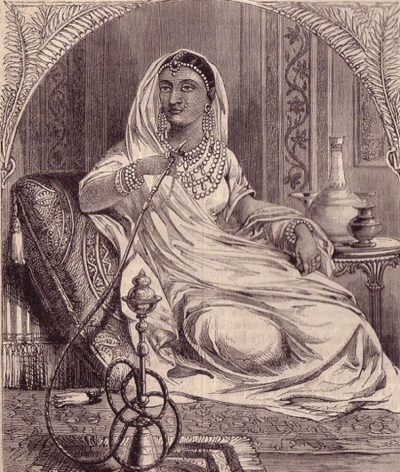

The notion of a warrior woman, who leads the fight against occupying forces is something which quite a common trope of legend and lore worldwide. The family tree includes the likes of

The notion of a warrior woman, who leads the fight against occupying forces is something which quite a common trope of legend and lore worldwide. The family tree includes the likes of  In June 1857, rebel soldiers seized the fort at Jhansi and massacred, not only the officers garrisoned there, but their families. After the rebels left, Lakshmibai took over, running Jhansi on behalf of the British until they could send a superintendent. That’s not exactly Joan of Arc-like… Instead, she fought off efforts by the rebels to claim the Jhansi throne for her husband’s nephew, as well as an attempted invasion by neighbouring states. It’s possible the latter enemy’s alliance with the British helped sour relations between them and Lakshmibai, though she still seems to have intended to act as a caretaker to this point.

In June 1857, rebel soldiers seized the fort at Jhansi and massacred, not only the officers garrisoned there, but their families. After the rebels left, Lakshmibai took over, running Jhansi on behalf of the British until they could send a superintendent. That’s not exactly Joan of Arc-like… Instead, she fought off efforts by the rebels to claim the Jhansi throne for her husband’s nephew, as well as an attempted invasion by neighbouring states. It’s possible the latter enemy’s alliance with the British helped sour relations between them and Lakshmibai, though she still seems to have intended to act as a caretaker to this point. Her post-rebellion legacy was a complex one. Some English writers maligned Lakshmibai, blaming her for the massacre by the rebels at Jhansi – in particular army doctor, Thomas Lowe, who called the queen the “Jezebel of India.” However, Sir Hugh Rose, commander of the British forces who took Jhansi spoke of her in much kinder terms, calling her “Personable, clever and beautiful,” “The most dangerous of all Indian leaders,” and “The bravest and best military leader of the rebels”.

Her post-rebellion legacy was a complex one. Some English writers maligned Lakshmibai, blaming her for the massacre by the rebels at Jhansi – in particular army doctor, Thomas Lowe, who called the queen the “Jezebel of India.” However, Sir Hugh Rose, commander of the British forces who took Jhansi spoke of her in much kinder terms, calling her “Personable, clever and beautiful,” “The most dangerous of all Indian leaders,” and “The bravest and best military leader of the rebels”. More than five years ago, in March 2014, we wrote about the

More than five years ago, in March 2014, we wrote about the

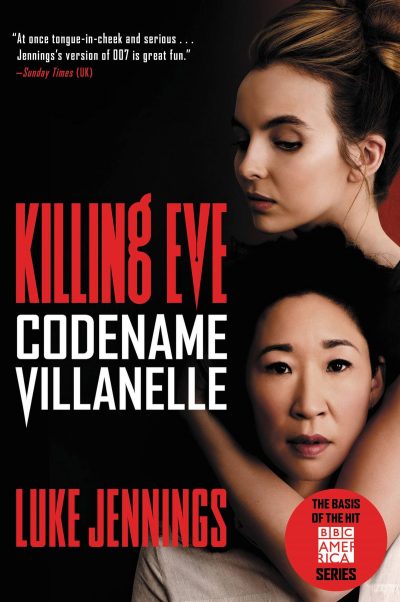

Villanelle

Villanelle Eve Polastri

Eve Polastri Eve vs. Villanelle

Eve vs. Villanelle Atone (February 26)

Atone (February 26) Fighting With My Family (February 14)

Fighting With My Family (February 14)